Kevin Francis Sullivan, the Boston-born wrestler and booker who helped usher professional wrestling into its modern era of heightened theatricality, died on August 9, 2024, in Concord, Massachusetts. He was 75 years old.

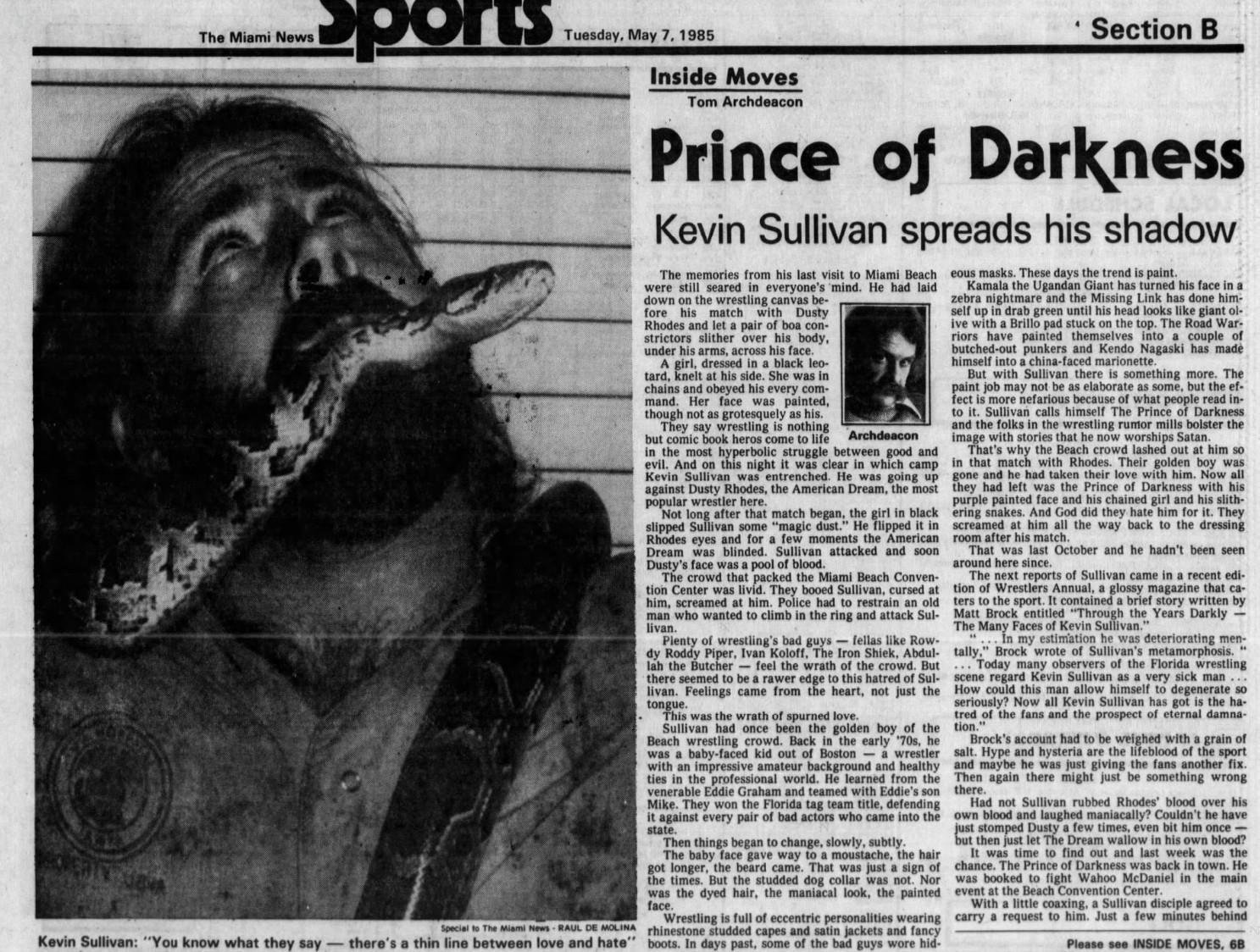

For wrestling fans of a certain age, Sullivan will forever be remembered as “the Taskmaster,” the diabolical leader of World Championship Wrestling’s cartoonish Dungeon of Doom stable. But his work as “the Prince of Darkness” years earlier in Championship Wrestling From Florida truly cemented his legacy as one of the industry’s most innovative minds, both in and out of the ring.

Born on October 26, 1948, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Sullivan grew up in a tough, working-class, Irish neighborhood. In a 2024 interview with Devon “Hannibal” Nicholson, Sullivan elaborated on his childhood. “My dad was a cop, and we were in a real Irish neighborhood,” Sullivan explained. “We did the normal things kids do—run the streets, play baseball, football, basketball. I wasn’t great at basketball.”

Despite his relatively small stature—Sullivan stood at only 5-foot-9—he developed a passion for amateur wrestling, competing at the local YMCA and boys’ clubs, and weightlifting, in which he started training at age 8. He went on to fashion one of the most impressive lower bodies in modern pro wrestling history.

Sullivan’s entry into professional wrestling came through an unconventional route. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he received no formal training outside of his work at the Y. Instead, his “wrestling school” was the family television, where he would spend Saturday mornings watching matches and studying the craft. “I got to see when I was a kid all the great ones—Buddy Rogers, Pat O’Connor, Édouard Carpentier, Haystack Calhoun, Yukon Eric,” Sullivan recalled.

His love for wrestling was nurtured by the local scene in Boston. He described the ups and downs of the territory in his interview with Nicholson: “When they had it on television, they had numerous sellouts of the Boston Garden. [Killer] Kowalski was very, very hot.” However, the landscape changed when wrestling went off TV in the area: “When it dropped off TV, they, instead of going to Boston Garden, they went to Boston Arena,” Sullivan remembered. “It slowly dropped off because he stopped bringing in talent.”

This autodidactic approach would serve Sullivan well throughout his career, as he proved to be a sponge for knowledge, soaking up insights from veterans wherever he went. His first professional match occurred in Montreal. From there, Sullivan began a journey that would take him through nearly every major wrestling territory in North America. In the early 1970s, he competed as “Johnny West” in the National Wrestling Alliance’s Gulf Coast Championship Wrestling before arriving in CWF in 1972. There, his fortunes improved greatly, as he formed a tag team with Mike Graham, son of promoter Eddie Graham, and captured the NWA Florida Tag Team Championship, working as a well-built good guy for most of the 1970s. This partnership with Graham would prove crucial to Sullivan’s future success, though not without some initial friction.

Steve Keirn, a mainstay of the Florida territory and a childhood friend of Mike Graham who later wrestled as Skinner in the WWF, initially found Sullivan’s constant presence and efforts to ingratiate himself with the Graham family infuriating. In his autobiography [coauthored by Ian Douglass, who also writes for The Ringer], Keirn recounted a car ride where he finally confronted Sullivan about his behavior.

“Kevin, there’s no use in hiding this. I always used to think you were a real suckass to Mike Graham,” Keirn told Sullivan bluntly. “You would kiss Mike’s ass in the ring, out of the ring, in the boat, or wherever. I couldn’t stand it!”

Rather than take offense, Sullivan simply smiled. “You know something: You’re right. I was,” he admitted. “But guess what: Nobody takes care of my family but me. So should I worry about you thinking I’m a suckass, or should I do what I have to do so that I can get as much out of this business as I can?”

This moment of candor changed Keirn’s perspective, helping him to view wrestling more as a means to earn a living rather than just a social club. It also sparked a friendship between the two men that would prove beneficial when they reunited in the NWA’s Georgia territory years later. Keirn credits Sullivan with eventually helping guide his physical transformation into a genuine hardbody, which indirectly led Memphis promoter Jerry Jarrett to pair Keirn with Stan Lane for a lucrative run as the genre-redefining, pretty-boy tag team the Fabulous Ones.

Sullivan’s time in Florida wasn’t just about politicking, however. He was also absorbing knowledge. B. Brian Blair, another Florida wrestling stalwart, notes that “Kevin learned a lot from the same man that taught me so much about the business, Eddie Graham, one of the greatest psychologists the wrestling industry has ever known.”

Eddie Graham saw potential in Sullivan. “Eddie really liked Kevin,” Blair continues, “especially because of the fact he could work with Eddie’s son, Mike Graham, who was a tremendous talent and was also about the same height and build as Kevin.”

Sullivan’s journey then took him to the West Coast, where he performed as a babyface for Roy Shire’s Big Time Wrestling in San Francisco. This stint exposed Sullivan to a different style of wrestling and crowd reaction—lots of big, Ray Stevens–style bumps and fast-paced antics—further broadening his understanding of the business.

As the 1970s gave way to the 1980s, Sullivan again became a journeyman, working across various territories and continuing to evolve his in-ring persona. During this period, Sullivan began experimenting with darker, more complex character traits—the first seedlings of what would later blossom into his infamous “Prince of Darkness” persona. The Georgia territory proved to be a crucial testing ground for Sullivan’s evolving heel character.

His first full-fledged heel turn came there later that year when he captured the NWA National Television Championship from Keirn on November 29, 1980. This victory marked a turning point in Sullivan’s career, as he began to fully embrace the dark side of professional wrestling.

Sullivan’s persona continued to develop after he ventured into Memphis in 1981. There, he aligned himself with Wayne Farris (who would later gain fame as the Honky Tonk Man) under the management of Jimmy Hart. This run in Memphis, a territory known for its intense brawls and over-the-top characters, allowed Sullivan to push his villainous character even further in bouts against Keirn and local legend Jerry Lawler, setting the stage for his eventual transformation into one of wrestling’s most notorious heels.

However, Sullivan’s return to Florida in 1982 would forever change the course of his career—and, in many ways, the entire wrestling business. There, Sullivan became the Prince of Darkness, a cult leader who invoked the powers of dark spirits in his promos and matches. This character was a direct response to the cultural zeitgeist of the early 1980s, which was caught in the throes of both the satanic panic and a horror film revival.

Sullivan and rebranded “evil” versions of established wrestlers such as amateur great Bob Roop (working for Sullivan as Maya Singh) and hard-core legend Mark Lewin (as the Purple Haze) formed the Army of Darkness. The stable was rounded out by charismatic mouthpieces such as scarred veteran King Curtis Iaukea and longtime manager Sir Oliver Humperdink, as well as the glam-meets-goth valet “the Fallen Angel”—Sullivan’s future ex-wife, Nancy Toffoloni.

The Army of Darkness, with all its members hamming it up for the camera, offered a cheat code of sorts for generating heat based on audience fears of hidden satanic messages in popular music and other forms of lowbrow entertainment. Sullivan, his Boston accent as thick as ever, would grab the mic and ramble into mystical territory. In “Superstar” Billy Graham’s autobiography, Sullivan claimed he “used a lot of terminology that suggested Satanism. One valet was the Fallen Angel. I’d cover the face of another one, The Lock, to keep out ‘the force of light.’ When The Lock teamed with Luna Vachon, I called them the Daughters of Darkness.”

Sullivan’s creative process for his satanic gimmick evolved over time—but it was, he maintained in the autobiography, never explicitly ‘satanic’: “The funny thing was that I never used the word ‘Satan.’ People just took that on their own. I’d make reference to the Chairman of the Board and Abudadeen, but that name was based on a Hindu fertility god I heard about during a trip to Malaysia.” As he noted in an interview with syndicated columnists Marilyn and Hy Gardner, “I’m not an advocate of the devil,” only someone with “super-strong mind power.”

While this might all seem like divine nonsense, Sullivan’s three-ring circus set the stage for innovative storytelling that pushed the boundaries of what was possible in wrestling. For instance, he worked with “Superstar” Graham on an angle in which Graham purged himself of sin in the desert to prepare for a battle with Sullivan.

As Sullivan himself recounted in Graham’s autobiography, “Billy went away for a few weeks. He went to Arizona, and took these pictures in the desert. Not video, but still pictures—we used the still pictures on TV with voice-over. It had never been done in the wrestling business before. His arms are stretched out, like he’s crucifying himself in the desert, to purge himself of his sins, and of Kevin Sullivan.

“Subliminal messages were very much a part of this presentation,” Sullivan continued. “Billy’s wearing white now. He’s fighting for the sins of the world. He’s walking in the light. When you have blood on those white tights, it’s symbolic, like the devil is re-crucifying Christ.”

This level of creativity and willingness to push boundaries made Sullivan must-see TV, even for his fellow wrestlers, including Syracuse University amateur wrestling star Mike Rotunda, who would later work extensively with Sullivan and whose sons, Taylor (Uncle Howdy) and Windham (the late Bray Wyatt), certainly borrowed from Sullivan’s supernatural playbook, recalled to The Ringer, “I was down in Florida as a babyface when Kevin was starting his demonic stuff, and I thought that devil gimmick was pretty crazy. I mean, it was different for sure, and it made things a lot of fun when I got to work some matches with Kevin.”

Rotunda added, “Kevin had a great mind for the creativity of the business, but he was definitely off the beaten path with a lot of his ideas. He was always trying to do things that had never been done, and a lot of it is stuff you simply couldn’t do in this day and age. I remember watching a lot of what he was doing down in Florida after I left and thinking, ‘How the hell is he getting away with that?!’”

Indeed, Sullivan’s antics often pushed the envelope to the point where it’s fair to say he didn’t always “get away with” them. One particularly memorable incident occurred on November 8, 1985, at Nassau Stadium in the Bahamas, where Sullivan faced “the Haitian Sensation” Tyree Pride for the Bahamas heavyweight title.

In an interview for Douglass’s book Bahamian Rhapsody, Pride recalled the intensity of Sullivan’s character work: “When Kevin had an interview and you saw it on television, you had to come see Tyree beat the hell out of Kevin Sullivan. He had more gimmicks than anyone else I’d ever seen.”

These gimmicks included snake charming, which terrified the ophidiophobic Pride. “Before one of his interviews, Kevin asked me, ‘Hey, Tyree ... can I throw this snake on you?’” Pride remembered. “I’m sure someone told him I didn’t like snakes, and that’s why he asked me that. There was no way in hell I would let him do that to me!”

The match itself was a powder keg of tension; promoter Charlie Major Jr. laid out a provocative finish that involved Sullivan and Lewin hanging Pride from the cage. Sullivan, aware of past times when wrestlers had been injured by overzealous fans, was initially hesitant.

“I asked him, ‘You want me to hang a Black guy ... out there?! There would be no protection for me!’” Sullivan recounted in the same book interview. “Then Charlie Major said, ‘Don’t worry, Kevin; I’ll be there to make sure you get back OK.’ I didn’t really believe him.”

The match went ahead as planned, with Sullivan opening a deep cut on Pride’s forehead. “The blood was shooting out of my head and hitting people in the third row,” Pride recalled. “Everybody wanted to kill Kevin Sullivan right then, from that alone.”

When Sullivan and Lewin mimicked hanging Pride from the cage, the crowd erupted. “People were throwing rocks, bottles, conch shells, and whatever they could get their hands on at the bad wrestlers,” Pride said. “It was a disaster.”

Sullivan managed to escape, but only by using Major as a human shield. “I opened the door, and the fans started to come after me,” Sullivan said. “That’s the most threatened I’d ever felt in my entire career. I immediately grabbed Charlie Major, held him up, and used him as a human shield all the way back to the locker room. I was completely unscathed; Charlie needed 47 stitches.”

The spot was taken so seriously that Sullivan and Lewin were arrested and charged with assault, though the charges were later dropped once Pride himself talked with the police. Despite the chaos—or perhaps because of it—the angle was a massive success. As Pride noted for Bahamian Rhapsody, “Nobody ever drew more money in the Bahamas than me and Kevin Sullivan.”

Sullivan’s knack for generating heat and creating memorable characters would serve him well as he transitioned into the national spotlight with Jim Crockett Promotions, which would later become World Championship Wrestling. In 1987, he formed the Varsity Club with Mike Rotunda and Rick Steiner, amateur wrestling–style heels that seemed at odds with Sullivan’s satanic persona.

Rotunda tells The Ringer: “That was kind of a strange arrangement for sure because it was the devil worshiper with two so-called All-American wrestlers. But that was the weird thing about it. You wouldn’t have thought that would work. Normally when you had guys working with the amateur, All-American type of gimmick, they were babyfaces. Well, we were heels. Kevin was the demonic coach of the two amateur wrestlers that became pros, and it was definitely a weird dichotomy, but it worked so well.”

The success of the Varsity Club—and its eventual dissolution—led directly to the formation of the long-running, University of Michigan–letter jacket–clad Steiner Brothers tag team, demonstrating Sullivan’s influence on all facets of the wrestling business.

As WCW entered the 1990s, Sullivan’s on-screen presence began to wane, but his influence behind the scenes grew. He transitioned into a role as a booker, helping to shape story lines and develop talent. This period saw Sullivan create stables such as the Three Faces of Fear (featuring himself, Ed “Brutus Beefcake” Leslie, and John “Avalanche” Tenta) and the Dungeon of Doom, which included a host of former Hulk Hogan opponents.

On the creation of the Dungeon of Doom, Sullivan revealed some of the politics involved: “I had to get [Hogan’s] faith because he was the one that suggested me for the job,” Sullivan said. “I gave him the guys that he had worked with before, that he was comfortable around, that were easy to work for him.”

He added, with a hint of self-deprecation: “When I was doing it, I felt like I was coming out of the clown car, because I had been such a staunch heel and I’ve got all these characters around me, and [at first] it didn’t work, but in the long run it did.”

While Sullivan’s in-ring career was impressive, his work behind the scenes as a booker truly set him apart. And he put that status to work in a groundbreaking angle involving Brian Pillman in WCW. That “Loose Cannon” story line blurred the lines between reality and fiction in a way that was unprecedented in professional wrestling.

As 1995 drew to a close, ex–Cincinnati Bengal Pillman began to fully embody his unhinged persona, radically altering his appearance and behavior on and off camera. Gone was the clean-cut “Flyin’ Brian” of old. In his place stood a volatile, unpredictable force that even his allies in the Four Horsemen struggled to control. Pillman’s new look—complete with leather vests, sunglasses, and provocative T-shirts—was matched by increasingly erratic behavior that left fans and fellow wrestlers alike wondering where the line between reality and fiction truly lay.

Sullivan, recalling this period in his 2024 interview with Nicholson, noted, “Nobody liked Brian at that time. They thought he was crazy; they thought there’s something wrong.”

The angle reached its zenith in a series of worked shoots that pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable in professional wrestling. At SuperBrawl VI in February 1996, the Loose Cannon truly went off the rails. In an “I Respect You” strap match against Sullivan himself, Pillman shocked the wrestling world by breaking kayfabe on live pay-per-view. After losing the match, Pillman grabbed the microphone and uttered the words that would change the course of his career: “I respect you, booker man.”

By acknowledging Sullivan’s behind-the-scenes role, Pillman had crossed a line that few in the industry dared to approach. The fallout was immediate. The next day, Eric Bischoff, the WCW president, fired Pillman from the company.

While Bischoff would later explain that this was all part of an elaborate work—a plan to send Pillman to Extreme Championship Wrestling to further develop his Loose Cannon persona before a triumphant return to WCW—the reality proved far different. Pillman, fully embracing his newfound notoriety, negotiated a lucrative contract with WWF, leaving WCW in the dust.

In 2000, after the demotion of Ed Ferrara and Vince Russo, Sullivan was promoted to head booker. This move may have precipitated the departures of several top stars, including Chris Benoit, Dean Malenko, Eddie Guerrero, and Perry Saturn, who all immediately signed with the World Wrestling Federation.

Benoit’s history with Sullivan may have played a role in his departure—Sullivan’s ex-wife, Nancy, had left him for Benoit in 1997 after they participated in a story line in which the two men were fighting over her. The personal drama had become entwined with professional story lines, creating a tense work environment that ultimately contributed to WCW’s decline. In 2007, Benoit killed Nancy (his wife at the time) and their son, Daniel, before killing himself. That cast a long shadow over Sullivan’s life, and he went on to give many interviews about those tragic events.

After WCW’s sale to WWE in 2001, Sullivan worked the independent circuit, making occasional appearances for various promotions. He made an appearance in Total Nonstop Action Wrestling in 2003 and later worked for promotions like Ring of Honor and various independent organizations.

As much as any wrestler before or since, Sullivan understood the business of professional wrestling at its core. As he told Steve Keirn, it wasn’t about being liked or making friends—it was about doing what was necessary to succeed in a tough, competitive industry that lacked a safety net. In spite of that, he was a mentor to many, always willing to share his knowledge and experience with younger talent like Mike Rotunda.

The Prince of Darkness may have taken his final bow, but the stories he told, the characters he developed, and the lessons he imparted will outlast him. His ability to blur the lines between reality and fiction, push creative boundaries, and adapt to the changing landscape of wrestling ensures that his influence—seen in stables like today’s Wyatt Sicks—will resonate in the squared circle for generations to come.

Ian Douglass is a journalist and historian who is originally from Southfield, Michigan. He is the coauthor of several pro wrestling autobiographies, and is the author of Bahamian Rhapsody, a book about the history of professional wrestling in the Bahamas, which is available on Amazon. You can follow him on Twitter (@Streamglass) and read more of his work at iandouglass.net.

Oliver Lee Bateman is a journalist and sports historian who lives in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter (@MoustacheClubUS) and read more of his work at oliverbateman.com.