1.

In 1972, the Portland Beavers, Oregon’s minor league baseball team of 69 years, relocated to Spokane. Fans grieved, but they assumed nothing could be done. Depressed sportswriters declared baseball dead in Portland.

Then a swashbuckling former television actor decided to resuscitate it.

His name was Bing Russell. He’d achieved semi-fame in the 1960s playing Deputy Clem Foster on a show called Bonanza. Before that, he’d spent the 1948-49 baseball seasons playing pro ball with the Carrollton Hornets, of the Class D Georgia-Alabama League. The Hornets were an independent outfit, meaning they were not affiliated with a major league club, as most teams in baseball’s lower castes were in 1948—and as all would be by 1972. But independent baseball had once flourished in America, and Bing thought it could again. In Portland, he sought to prove it. He paid $500 for an expansion spot in the Class A Northwest League, relocated his family, and announced that an independent team called the Mavericks would debut that summer.

Portland was incredulous. Major league affiliation comes with major league funding. Player scouting, salaries, insurance—for affiliated teams, all this is taken care of. Russell was furnishing the Mavericks by himself; the roster he rubber-banded together (through open tryouts) included a 30-year-old high school English teacher, a left-handed catcher, and a former restaurant manager. He paid players just $300 per month. Fans thought the Mavericks would get beat up conspicuously by the better-funded, buttoned-up competition. Some thought the whole thing was probably a joke.

We want to help lead the biggest comeback in the history of sports.Paul Freedman

It ended up being very serious. The Mavericks finished the season in first place. Their style of play—at once piratical and insouciant, all facial hair and visible paunches, stolen bases and punched umpires—confounded baseball but captivated baseball fans. The team was profiled in The New Yorker and Time; Russell was interviewed by Johnny Carson.

And they delighted Portlanders. Once, with the Mavericks on the brink of a series sweep, infielder Joe Garza clambered atop the home dugout, lit the bristle end of a broomstick on fire, and swung it around his head like a battle flag to rally the crowd. Soon, fans were bringing their own broomsticks to the ballpark. Helicoptering them alongside Garza at the end of a successful series became a sacred Mavericks ritual. (Fans were not permitted to light their broomsticks on fire, unfortunately.) The Mavericks went on to break Class A attendance records. After the 1974 season, Russell was named Class A executive of the year. “The summer of 1973 was the best of my life,” he relayed to a reporter in footage featured in the 2014 Netflix documentary about the Mavericks, The Battered Bastards of Baseball. Portland concurred. The writers who’d declared baseball “dead” in the city credited the Mavericks with bringing it back to life.

Fifty-one summers after the Mavericks debuted, two former high school classmates from Oakland are attempting effectively the same thing, only with higher stakes and longer odds. Their names are Paul Freedman and Bryan Carmel. Both are in their mid-40s, married, fathers to pubescent children. The team they’ve started is called the Oakland Ballers. They debuted this June.

When Paul and Bryan first asked to meet me, last August, to share their still-secret plan for starting the Ballers, I wasn’t sure what to think of them. A quick LinkedIn search confirmed neither was a schlub. Bryan’s a filmmaker and producer based out of Los Angeles, and Paul, who still lives in Oakland, has started and sold several small start-ups, mostly in education. In person, they’re likable and distinct: Bryan tall and bespectacled and wry, like a pot-smoking professor at a liberal arts college; Paul impish and unrelenting and short, a textbook businessperson, part bulldog, part bantamweight.

And their ambitions for the Ballers were admirable. Like other recent successful sports start-ups—the nearby Oakland Roots, of the USL Championship; Angel City FC, of the NWSL—the Ballers aspired to be a different kind of sports organization. Capitalistic and competitive, sure, but also purpose built and community driven. They wanted to win games and sell tickets, Paul and Bryan said, but also mean something to the people they sold tickets to. No small thing in a sports town on the brink of losing its third major league franchise in less than five years. “We want to help lead the biggest comeback in the history of sports,” Paul told me when we eventually met in person, at a bar uptown. “And become a legitimate community asset,” Bryan added. As a depressed lifelong Oakland sports fan, I admitted that sounded pretty good.

And yet. Most team owners profess to be community driven when they’re preparing to ask that community for something. And it was not obvious what sort of citywide comeback a team like the Ballers would be able to lead. Paul and Bryan had arranged for the Ballers to play in the Pioneer League, an independent “partner league” near the bottom of organized baseball’s classification schema (a rung or two lower, technically, than where the Mavericks competed, in the Single-A Northwest League).

What is a partner league? The minor leagues most of us are familiar with—Triple-A through rookie ball—today consist entirely of affiliate clubs. That is, teams that are controlled and funded by major league organizations. This is as it was in 1972. Unlike in 1972, an ecosystem of successful independent leagues has taken root below and apart from the minor leagues. This is independent baseball. The independent leagues lean scraggly, but MLB recognizes the four most legitimate and high-striving ones as “partner leagues,” meaning it leverages them to do things such as test out rule changes, and MLB teams can purchase player contracts.

Partner league baseball is fine baseball. The parks teams play in are small, but their intimacy puts fans closer to the game. The competition’s solid, especially since MLB culled its draft from 40 rounds to 20 in 2021. Most importantly, MLB can’t tell the teams what to do. Problem is, even the most successful partner league teams average only a few thousand fans a game. Players are playing for an (often final) chance to play somewhere else. The gameplay represents a heavy step down, in terms of pedigree and scale, from what Oaklanders are used to. Would Oaklanders support that?

“My willingness to be excited about an alternative baseball team was limited,” Leigh Hanson, chief of staff to Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao, told me last fall. Hanson noted that, with its loss of major sports teams, Oakland is facing a perception that it is a minor league city. “To bring in an independent league or a minor league team in some ways confirms that,” she said.

Further, most independent or minor league teams that achieve the sort of goals Paul and Bryan were setting out to achieve come with certain resources—usually billions of dollars or megawatts of celebrity. Angel City FC, which was started in 2020 and is now the most valuable women’s sports team in the world, had both; it counted among its early ownership group Natalie Portman, Billie Jean King, and Alexis Ohanian.

Paul and Bryan are not Natalie Portman. They’re not even Bing Russell. The furthest either Paul or Bryan had progressed athletically in school was JV baseball. Prior to starting the Ballers, they’d related to pro sports the way most of us do: purely as fans.

And was uplifting America’s most downtrodden sports town something just fans—in a league like the Pioneer League—could do?

To be sure, it wasn’t something fans often do. One reason: It’s hard. “I was sleeping on an air bed eight years ago,” Jesse Cole, founder of the Savannah Bananas, a popular barnstorming organization, said. “My wife and I had to sell our house, empty out our savings account. We were $1.8 million in debt.”

Edreece Arghandiwal, cofounder of the Oakland Roots, has a similar story about his early days, though he was sleeping out of his car as opposed to on an air bed. “It takes tremendous guts,” he said.

What’s more, Paul and Bryan were set on debuting the Ballers in the summer of 2024. That meant they needed to build a business, build a baseball organization, assemble and prepare a team, and construct a stadium—as well as convince the world’s most disillusioned sports market to be open to the magic of minor minor league baseball—roughly in a span of nine months. (Oh, and because the Pioneer League requires an even number of teams, they’d also have to help spin up a second Northern California expansion team while building the Ballers.)

“It’s never been done before,” Mike Shapiro, the president of the Pioneer League, told me. “They came to me and said, ‘We’re going to put a Pioneer League team in Oakland, the 10th-largest market in the United States, a city that has had to live through heartbreak, and we’re going to build our own ballpark.’ Anybody looking at that on paper would have gone, ‘Are you guys out of your mind?’”

Before it was over, Paul and Bryan would concede that maybe they had been. As Paul, sleep deprived and sunburned, confided to me one afternoon in May, amid the clank and whir of stadium construction that he was not certain would be complete before Opening Day, “We had no idea what we were getting ourselves into.”

Nevertheless, I wanted to believe in what Paul and Bryan were building. Growing up as an Oakland sports fan, I thought of the A’s more as a kind of church or nation-state than as a product. My relation to them was tribal far more than transactional. Then I was forsaken. And I was tired of feeling like there wasn’t anything I could do about it. I wanted to believe I could exercise greater agency in my relationship with the sports industry, even insist upon some kind of stake in it, the way fans do in Europe. And I wanted to believe Paul and Bryan were offering a pathway for that.

“We want to go about this very differently than the A’s,” Paul told me once. “If we’re taking this from the community interest perspective, what can a bunch of people willing to work really hard and have access to networks and in some cases capital, what can we do to bring something that actually makes the most sense for the community?”

I was also curious—about what starting a professional sports team requires; about whether it’s actually possible. This curiosity was a product, I thought at first, of too many hours spent playing “owner mode” on MVP Baseball 2005 or watching Moneyball one too many hundred times in college. But I’ve wondered lately whether it’s something many of us think about, perhaps passing by an old stadium or glancing up at the owners’ box during a game or sitting at the bar after a bonehead signing or bad loss. You wonder briefly what it’d be like when your friend flicks his eyes from the TV and suggests daringly over his pint: Fuck it, what if we just started our own team?

Well, what if? What would it take? Is it possible? Paul and Bryan were about to find out.

2.

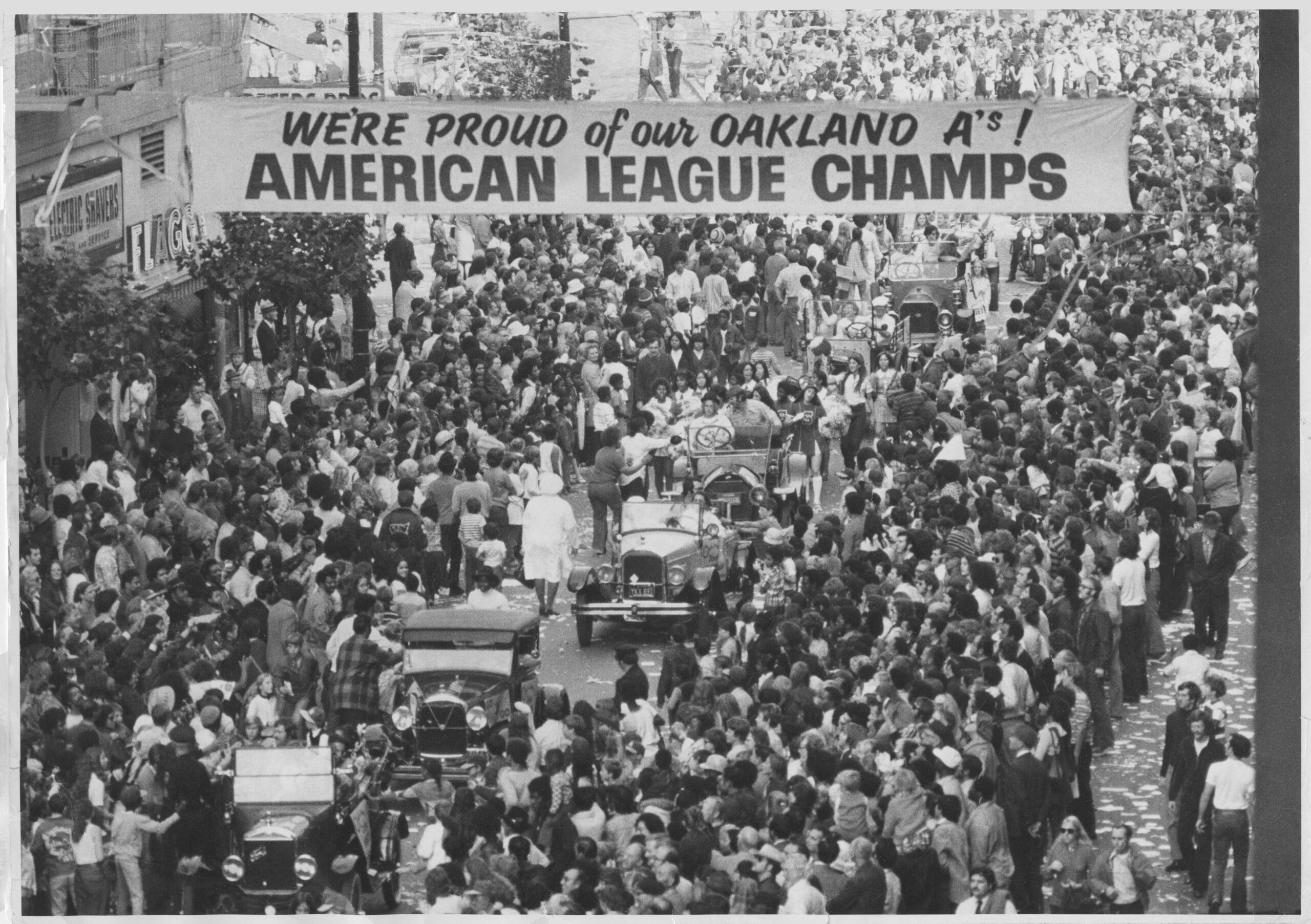

Oakland’s been a sports town for about as long as it’s been a town. “Our Hopes and Prides Win the 1912 Pennant,” read the headline in the October 28, 1912, edition of the Oakland Tribune, after the Oakland Oaks won the Pacific Coast League championship for the first time. “It would be an understatement to say … the joy was unconfined,” Tribune columnist Ray Haywood reported 36 years later, when the Oaks won their final PCL pennant. “The crowd began to fill the stands at 11 a.m. … The influx discommoded several people who, it was said, had slept in the right field boxes all night.”

The enthusiasm stems from an original striving. Oakland boosters always dreamed of turning the city not just into a satellite of San Francisco, but its economic rival and cultural antipode. In its early sports teams—not just the Oaks, but the various independent, minor, and Negro league teams that played in the city throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, such as the Commuters and Larks—such dreams found expression. In the mid-20th century, when Oakland deindustrialized, lost its tax base, and rammed freeways down the middle of its most historic neighborhoods, the dream faded. Then the major league teams arrived—the “Just win, baby” Raiders and their demonic Black Hole; the “Swingin’ A’s” and their Mavericks-esque mustaches—and they brought back to Oakland glory and status. They created raucous community spaces and supported productive youth leagues. And through their magnetic, marauding swagger, they articulated all the coolest parts of the East Bay ethos. The East Bay was a place with a chip on its shoulder and a clenched fist on its chest. The same seemed true of its teams. Fans loved them for it.

Popular culture credits the Raiders of the 1970s with being the best example of this effective symbiosis, but in truth, the high-water mark of Oakland sports might have come with the A’s dynasty of the late ’80s and early ’90s, when the Oakland Coliseum hosted the MLB All-Star Game and three World Series. This was the Oakland sports scene Paul inherited. Small, brainy, a little awkward, Paul moved to Oakland in 1992, at 14. The move was tough on him, and he was lonely. But he met Bryan—as well as his future best friend Bobby Winslow, a charming and athletic kid who lived close by—riding BART to A’s games after school. They burned summers in the Oakland Coliseum bleachers, watching Rickey Henderson steal bases. (When they weren’t at the Coliseum, they were playing pickup near Paul’s house, Bobby usually throwing down.) For Paul, his affinity for the A’s morphed into a sense of affiliation. He attended college in Chicago, but he came back after graduation, raising his family here, even headquartering a few of his companies in offices across the 880 from the Coliseum, off Oakport Street—in part so he could more easily get to games. “Being an A’s fan was a big part of me starting to identify as an Oaklander,” Paul told me at the bar last fall.

It was the threatening of that identity, 30 years later, that inspired the Ballers. Paul had been among the thousands of A’s fans who’d fought back vigorously against A’s owner John Fisher when he first angled to uproot the A’s to Las Vegas in the early 2020s, and he was among the 30,000 who assembled in the Oakland Coliseum parking lot for a “reverse boycott” of Fisher’s betrayal in 2023.

What Fisher sought to dispossess Oakland of, in Paul’s mind, was far more than just a business or even a beloved team, but a cornerstone of the East Bay’s self-conception, and its importance to Oakland felt well-evidenced by the reverse boycott. The boycott had been designed to prove that Oakland remained a vociferous sports town deserving of teams that loved it back. Paul left convinced and inspired. He texted Bryan, who was in L.A. (Bryan, a member of the WGA, was on strike.) “I have a crazy idea,” Paul wrote. “I like crazy ideas,” Bryan replied.

The first thing they decided on was the name. It came from Bobby. Back on the Oakland blacktops where Paul, Bryan, and Bobby had played pickup basketball, Bobby had made a bit of referring to himself, triumphantly, as “a baller.” Bobby died unexpectedly at 22 due to a heart complication. Paul and Bryan had been thinking of him throughout the A’s relocation attempt. Bobby had loved Oakland sports the most out of all of them; he was the reason Paul had become an A’s fan. It only felt right, now, that Paul and Bryan’s attempt to save baseball in Oakland included him. They imagined honoring Bobby with the name, but also by mentioning him at the Ballers’ inaugural home opener, should their “crazy idea” advance that far.

So what, then, does advancing this sort of idea require? Most tediously, it requires money. Not the eye-popping billions required to secure an expansion spot in the big leagues but not chump change, either. Getting the Ballers off the ground required around $4 million to start. There was the Pioneer League’s $1.7 million expansion fee to pay—later, there’d be a stadium to build, which would run the Ballers about $1.6 million—plus money for staff and player salaries, marketing, design, community events, legal fees, insurance, rent, merchandise, the list goes on. Paul and Bryan contributed personal funds and raised money from local investors—all surreptitiously at first, because, at that point, the Ballers were still a secret.

Next, you need to build the organization. You’ll need a business side—operations, chief of staff, marketing, sponsorships—and a baseball side. The baseball minds Paul and Bryan brought on included former major league catcher and Oakland son Don Wakamatsu as the Ballers’ executive vice president; former Giants first baseman J.T. Snow as a coach; and Micah Franklin, who is credited in baseball circles with fixing Cody Bellinger’s swing, as manager. Wakamatsu led the player-scouting and acquisition apparatus. Once, over Zoom—pausing occasionally to spit into a ceramic coffee mug—he introduced me to some of the players he and his assistant general manager, Tyler Petersen, were working to poach. All seemed pretty legit to me. A few possessed previous Pioneer League experience; others no doubt would have been drafted or playing affiliate ball before the minor leagues had contracted. He planned to build the roster through free agent pickups and fill it in with local open tryouts, Mavericks style. (Paul and Bryan had also committed to providing players housing during the season. Most independent league teams set players up with host families for the summer. Paul and Bryan planned to rent two large houses in West Oakland and put the players up in them.)

There’s a role for sports to play in creating a sense of belonging. The A’s were once a part of Oakland’s social fabric. The Ballers can be, too.Nikki Fortunato Bas, Oakland City Council president

Perhaps the most important work, however, is endearing yourself to the community you want to uplift. In a market like Oakland in 2024, this is especially critical. You have to convince customers you’re not carpetbaggers, that your team isn’t some kind of grift. Paul and Bryan took to the work with zeal. While Don and Tyler were building the baseball team, Bryan and Paul knocked on doors, canvased farmers markets, introduced themselves to the coaches at Greenman Field, the headquarters of Oakland Babe Ruth Little League. They conferred with local hip-hop legend Mistah F.A.B., beloved local sports reporter Casey Pratt (now working for the mayor), and Green Day frontman Billie Joe Armstrong, and they worked with fans on what they called a “Fans’ Bill of Rights,” which stipulated what commitments the Ballers would make to fans in return for their support. They met regularly with community leaders, like the civil rights organizer Lateefah Simon and West Oakland Councilmember Carroll Fife, on whom they made an impression. “Paul is super passionate about his love for this city,” Fife told me. “And when I said, ‘Well, I don’t do anything in the district without community input and outreach, and so I really need that to be central to the work that you’re doing,’ he was all in.”

All this crescendoed on a Saturday afternoon in early November, when Paul and Bryan convened a “secret meeting” of community ambassadors at a brick-laid workspace downtown. Each of the attendees Paul and Bryan had been courting for months. (“I think I know the color of all their cars,” Paul told me.) They included Jorge Leon, president of the Oakland 68’s, the city’s preeminent fan activist and supporters’ group; Leigh Hanson, the mayor’s chief of staff; Laney College head football coach John Beam; Simon; Oakland City Council President Nikki Fortunato Bas; and a slew of other community activists, coaches, sportswriters, teachers, and former athletes. They all listened over crooked elbows and with angled glares as Paul and Bryan, from the head of a horseshoe-shaped conference table, explained why they were starting the Ballers and what they wanted to do with them. “This is to be a team to be by Oakland, for Oakland, and that will never leave Oakland,” Paul said. His voice quavered slightly, seemingly from nerves, but when he finished, the room broke out in applause. “There’s a role for sports to play in creating a sense of belonging,” Bas said after. “The A’s were once a part of Oakland’s social fabric. The Ballers can be, too.”

Excitement about the Ballers grew further as winter fell. A formal announcement of the team came on November 28, at a press conference at Laney College. Mistah F.A.B. attended; so did the mayor. News of the announcement was picked up nationally, and the reaction in Oakland was reassuringly positive. “I don’t even like sports,” Simon, the community organizer, told me later that day. “But I can’t wait for that first Ballers game.”

Outwardly, Paul and Bryan stoked the excitement. “The history of baseball is so intertwined with the history of Oakland,” Bryan told the Los Angeles Times. “It is a baseball town. It needs a baseball team.” Behind the scenes, however, a problem was growing: The Ballers didn’t yet have a place to play.

3.

In the lower rungs of the sports industry, pro teams live and die by ticket sales. They’re the life source from which all your other revenue streams—concessions, sponsorships, parking—invariably draw. But how do you sell tickets without a major league product? First, you need to build a sense of kinship and trust with the community. (The Roots, you know if you live in Oakland, are a vibrant example of this. For the past two years, they’ve been selling out games even though they play in far-flung Hayward. Such is the loyalty their commitment to fans has engendered.) Next, you need to put on a good show. For this, the Savannah Bananas, who are presently selling out major league stadiums across the country, are the gold standard. From the choreographed dances players pull off mid-pitch to the baby races that Cole, the Bananas’ carnivalesque founder, facilitates between innings, fans know that when they buy a ticket to see the Bananas play, they’re going to have a good time.

Of course, you don’t need racing babies to sell tickets. As Frank Boulton, owner of the Long Island Ducks, of the Atlantic League, another MLB partner league, told me, “The simple mission at this level is to provide affordable family entertainment.” What you do need, however, is a venue.

Paul and Bryan knew this. Far from mere delivery mechanisms for good entertainment, great ballparks can function as compelling products unto themselves—delivery mechanism and destination all at once. Indeed, this was the kind of stadium Paul and Bryan wanted. To help them build it, they’d hired the consultancy design firm Canopy Team, whose cofounder Janet Marie Smith was a former vice president of planning and development for the Orioles and among the key architects of Camden Yards. Though the model Paul and Bryan returned to in their designs resembled a different classic, urban park. “It’s not a perfect comparison,” Paul told me. “But the feel we’d love to reproduce is Wrigley.”

The problem was, very few places that can accommodate even a DIY Wrigley exist in Oakland. Paul and Bryan’s original plan had been to try at Laney College, the junior college southwest of Lake Merritt, but there were “so many complications” with Laney, as Bryan told me once over Zoom, head in his hands. By January, they’d opted to go all in on what was probably their only other option: a public park in West Oakland called Raimondi Park.

It’s better than I expected. It’s beautiful. It feels like we’re on the precipice of change.Mistah F.A.B. on the renovated Raimondi Park

Raimondi is imbued with history. It’s named after former Oakland Oaks infielder Ernie Raimondi. Curt Flood and Frank Robinson grew up playing there. During World War II, it was the home field of the A-26 Boilermakers, an all-Black team of Oakland dockworkers. It’s kitty-corner to the historic 16th Street railroad station, a once-grand, since-abandoned structure built in Beaux-Arts style that served as the western headquarters of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the country’s first Black union. But the park was also wasted. The bathrooms were in ruins, the baseball field dilapidated. It lacked sidewalks. The dirt lots flanking the park contained 9,700 tons of contaminated soil. Abandoned rails bisected the unused roads. The road running the park’s western edge had once hosted Northern California’s largest community of unhoused people.

Turning Raimondi into a professional-grade park would require serious effort. But, first, it would require something perhaps even more challenging: navigating the bureaucratic back channels of Oakland City Hall. “We’ve burned the boats!” Paul exclaimed one morning last January, after he and Bryan signed the field rental agreement with the Oakland Parks and Recreation Advisory Commission, which allowed them to start selling tickets to future games at the park. And it was an important step. But they wouldn’t be able to start constructing the park until they’d secured several other sets of approvals and permits from the city—building permits, conditional use permits, approvals from the City Council, environmental reviews, right of entry agreements, an alphabet soup of acronyms and annoyances.

And getting those would prove stressful. I watched it age the Ballers staff in real time. One night in March, I met Paul and Bryan outside the Lakeside Park Garden Center, near Lake Merritt, for a parks commission meeting at which they were hoping to finally secure the right of entry and license agreements—the last steps before they could start building. The previous month’s meeting, before which they’d anticipated securing the same, had been postponed due to a lack of quorum. In the interim, they’d worked diligently, hiring Shereda Nosakhare, managing partner of Lighthouse Public Affairs, to help them convince the right combination of important people to prioritize their project. (“People ask us, ‘How did you go around Oakland’s approval process?’” Paul would relay to me later. “We didn’t go around it. We went through it.”) Now they just needed the meeting to happen. And they needed it bad; the clock was ticking.

I arrived slightly late, afraid I’d miss the vote, but when I pulled up I found Paul, Bryan, and Shereda slumped like question marks outside the garden center’s closed wooden doors, getting wet in a piddling rain. The meeting had been postponed once again.

Paul and Bryan wouldn’t receive final approval to start building the Ballers park until April 30. The Ballers’ home opener was scheduled for June 4. They’d have about a month.

Work began the afternoon the approval came down. I stopped by Raimondi that day. Backhoes were already tearing up the outfield grass, jackhammers disarticulating concrete slabs. Bundled pallets of wood and containers of prefabricated metal decorated the park’s exterior. Paul was there, orchestrating the chaos. He effectively wouldn’t leave for the next 35 days. Bryan, for his part, was now spending his weeks sleeping in a hotel in Oakland, flying to L.A. to spend choice Saturdays with his wife and kids, then flying back to Oakland Sunday night. “My wife’s got a very real job,” he explained to me that first afternoon at Raimondi. “And we don’t have a lot of childcare help or anything like that.” He trailed off, grimacing at a pile of scrap metal.

By this time, I’d been following Paul and Bryan for nine months, and I’d grown to root for them. They were passionate and sort of goofily unpretentious, delighted by the prospect of owning a professional baseball team and duly awed by it. And more than ever, I could see the value of what they were selling. There was everything going on with the A’s Oakland departure, of course, but in other cities, too—Pittsburgh, Chicago, Kansas City—team owners were maximizing profits by screwing over fans, proving the need for this fan-led movement. Paul and Bryan spoke often in interviews about creating a new “social contract” for sports in America. I was ready to sign.

But I’d also become genuinely concerned about their health. On top of working to market, prepare, permit, house, finance, and furnish the Ballers, Paul and Bryan were now trying to complete a very complicated construction project, in public and on a preposterously abbreviated timeline. As Tim Koide, the Ballers vice president of ops, told me, it was like “building a start-up while also running a political campaign while also putting on Woodstock all at the same time.”

“It’s the most stressful thing I’ve ever done,” Paul told me one afternoon, as stadium construction clanked and screamed around us. He paused, squinting against the sun, and wiped sweat from his brow. Across the park, Bryan was speaking passionately with people in hard hats. Paul watched him a moment. “I’m just thinking about when fans break into that first ‘Let’s go, Oakland’ chant. Then all this will be worth it.” It sounded like he was speaking more to himself than to me.

I visited Raimondi again some 48 hours before Opening Day. The entrance to the park remained all caution tape and loose wire, scaffolding and scuttled steel. Sawdust hovered in the air. Crews were just now starting work on the clubhouses, which were being fashioned out of the vacant warehouses that sat across the street from the park—which were still being cleared of detritus and refuse. A news helicopter hovered overhead, transmitting footage to fans following the progress on social media.

I found Bryan and Paul training a scrum of concessions workers and ticketing staff on game-day logistics. Anxiety radiated off them. Would the Ballers turn out to be a genuine community asset—even a halfway successful business—or would the team flop? I could see they’d been asking themselves that question. Neither had shaved. Their eyes looked like cracked phone screens. (“I had a few times waking up in the middle of the night thinking I’m gonna be the guy from Fyre Fest,” Paul told me later.)

I wondered, then, whether this was the hardest thing about starting something like the Mavericks or Ballers: the faith it demands in the face of the prospect that, in spite of all your hard work and good intentions, all your investment, you still might flop.

I’m just thinking about when fans break into that first ‘Let’s go, Oakland’ chant. Then all this will be worth it.Freedman

“It’ll literally fail if we are a beloved one-year [team],” Bryan said later that day. “Like, ‘Oh, remember when there was that community baseball team in Oakland? They tried. But they could never actually be a business.’ For all of the investment, the question remains: Will people come?”

In the end, they did. They came, first, as volunteers—hundreds in the final 48 hours before first pitch, there to help Paul and Bryan and the many other staff members, contractors, vendors, and city employees now present pick up trash, assemble furniture for the clubhouses, power-wash the walkways, paint crosswalks on the streets that had been fully repaved only the day before. Then, on Opening Day, they came as fans, this time by the thousands, a sold-out crowd of 4,200 clad in forest-green Ballers gear.

It was surreal arriving at Raimondi Park that afternoon to find so many people assembled there, milling about the freshly paved roads, strolling past street vendors frying vegetables and selling wares, pregaming in the gated dirt lots that Paul and Bryan had recently cleared of toxic soil. Fans were making signs on the hoods of their cars and drinking beer; dads and sons were playing catch. The airspace was charged with a festival mix of mariachi music and Mac Dre. It felt a bit as if fans had lopped off a wedge of what I’d loved most about baseball at the Coliseum and transplanted it 8 miles west, like pirates.

The surreality intensified as you entered the park. What recently had been a dirt patch—even more recently a construction zone—was now a minor league ballpark. Still a bit DIY, sure—with pop-up vendors and food trucks defining the park’s perimeter and everyone on staff frantically juggling multiple jobs at once—but a ballpark, no mistaking. Bleachers rose 40 feet into the air up and down the left and right field foul lines. Along the backside of the grandstands were graffiti murals paying homage to Oakland legends: Curt Flood, Frank Robinson, Bill Russell, Too $hort. On the facade of the old warehouse rising behind the third-base grandstands, a huge, white Ballers “B” had been painted. Music pumped out of a new PA system, which was controlled from inside the press box that Canopy had installed atop the grandstands the night before. Inside the main entrance, a small area for pictures and mingling had been arranged—strung with lights, hemmed in by the grandstands on one side and a gate on the other—and into it streamed a who’s who of Oakland sports and politics. Members of the Oakland City Council were there, beat writers, columnists from the San Francisco Chronicle, business owners—Angela Tsay, Oaklandish cofounder; Lindsay Barenz, president of the Roots—the mayor, and Mistah F.A.B., who walked in wearing a large, gold “DOPE ERA” chain that creased his XXL Ballers jersey. I asked him, later, whether this—the “hottest place to be” in Oakland, as Oaklandside reported the next day—had been what he’d expected.

“It’s better than I expected,” he said, clapping one of his giant hands on my back. “It’s beautiful. It feels like we’re on the precipice of change.”

If the vibes in the concourse spoke of new beginnings, the view from the seats, conversely, felt positively retro. The field sparkled like a new car, but the park surrounding it felt intimate and formfitting, integrated thoughtfully into the neighborhood. From field level, you looked up at ivy-strewn brick warehouses behind the left field wall, apartments and playgrounds behind the bullpens in right, and the misshapen downtown cityscape rising above the American Steel building in left center. To a baseball nerd, it felt heartening, a callback to baseball’s urban origins, when the sport was played among fire escapes and bodegas, sewer grates and bars, train stations and stoop-lined streets. To a fan forsaken, however, it also felt like something more—something like proof. Namely, that it was possible to uplift a downtrodden sports town with an independent baseball team; that a pro team need not be major league to become a meaningful community asset. “I think independent organizations can make it,” Bing Russell had once remarked to a reporter from the Eugene Register-Guard. “There are a lot of baseball towns in the U.S. that have lost out.” My impulse, at my seat, was to finally, vehemently agree.

I was well aware, however, that I’d allowed myself to get swept up in something and had probably lost my sense of journalistic objectivity. Luckily, I had my brother with me. My brother’s a baseball guy—he still plays hardball in his 30s—and a Giants fan. He’s also rather gruff, works in construction, and is not prone to sentimentalizing for romanticism’s sake. I nudged his arm. “So … what do you think?” I asked.

“Fucking great,” he replied. “Gives me Wrigley vibes.”

4.

Vibes, however, can change.

The Ballers lost that night, 9-3, but it barely seemed to matter. More remarkable was the fact that the Ballers had played a home opener at all. Those on hand felt they’d witnessed not just a baseball game, but an act of creation. “A new Field of Dreams rises in Oakland,” read a headline from reporter Reis Thebault in The Washington Post. That was victory enough.

Though tangible victories came, too. After the Opening Day loss, the Ballers won six of their next 10 games. They’d finish the first half of the 96-game Pioneer League season 27-21, good for fourth place, missing a first-half playoff spot by two games. (The Pioneer League doesn’t have a traditional playoff structure. Four teams make the playoffs: the teams with the two best records over the first half of the season and the teams with the two best records over the second half.) Starting pitcher Christian Cosby paced the league in strikeouts—he’d finish the first half of the season with 75—while speedy outfielder Austin Davis was among league leaders in stolen bases. Three Ballers pitchers—Elijah Pleasants, Danny Kirwin, Tyler Davis—had their contracts purchased by major league clubs. Fans were bullish about the team’s second-half chances. “Need pitching,” Bryan replied in an email when I asked him to corroborate that confidence, a nod to the great pitchers they’d lost. “But playing well.”

Success on the field translated into excitement off it. Ballers fan groups popped up on Facebook, and the Ballers Instagram account ballooned to nearly 30,000 followers, far more than any other Pioneer League team. Too $hort took to wearing a black Ballers hoodie during performances. Later, somewhere deep inside Rogers Centre in Toronto, Billie Joe Armstrong shared a video of himself spray-painting a Ballers “B” over an A’s logo that had been printed in a hallway.

The excitement had perhaps less to do with the Ballers’ on-field success than it did with the fact that they were making good on their promise to champion and partner with Oakland off the field. In July, they announced the launch of a community investment round, which would grant fans the chance at an ownership stake in the team, as well as input on certain organizational decisions—design changes, certain front office decisions, even stadium location, purportedly. As of this writing, more than 3,500 people have reserved shares. “They’ve shown us that they’re about the community and keeping pro baseball alive in Oakland,” Leon, leader of the 68’s, told me. (The 68’s are at every Ballers game now; you can find them parked down the left field line, their section demarcated by a long, black-and-white banner that reads, “Oakland Will Never Quit.”)

After the launch of the community investment round, however, something changed. The Ballers opened the second half of the Pioneer League season clumsily, dropping five of their first seven games. The skid had something to do with player morale, which had slipped. There were two reasons. The first had to do with housing. By July, discontent had grown among players over conditions at the houses Paul and Bryan had rented for them. They were too cramped, players reported to Bryan and Paul, and with 24 large and presumably smelly people sleeping on bunk beds and sharing what was, by this writer’s estimation, a wholly inadequate number of bathrooms, they were almost certainly right. (“We blew the housing, no doubt,” Bryan would later admit.) To their credit, Paul and Bryan heard the complaints and rented players a third, larger house. But in mid-July, the house was burglarized. A player’s car was stolen; another’s was broken into. Paul and Bryan put the players up in a hotel as they searched for something safer. They’ve since found new, more spacious accommodations, and they’ve partnered with Oakland PD to secure additional patrols for the area, but players were unnerved.

The second issue had to do with coaching. The team had lost more than a few close games on account of questionable late-inning decisions. And by the dawn of the second half, something had cracked in the clubhouse. Factions had formed; an atmosphere of apprehension and distrust had developed. According to coach J.T. Snow, who stepped away from the Ballers in July, a lot of that stemmed from Franklin, the head coach. “The players were confused about some of the things he was doing,” Snow told the San Francisco Chronicle. “There were some mixed messages. It was kind of a weird situation. … It wasn’t fun.”

On July 21, Bryan and Paul let Franklin go. It’s unusual for a baseball team to change managers midseason, and the news distressed fans. Then, two days later, agent Lonnie Murray requested immediate trades for each of the three Ballers she represented, including fan-favorite Austin Davis. In a tweet, she cited “poor trmt & highly unprofessional antics” as reasons. In subsequent tweets, she said Paul and Bryan had taken longer than they’d let on to secure players a third house and that Ballers medical staff had neglected to properly treat a thumb injury that another of her clients, Myles Jefferson, had suffered earlier in the season; as a result, she contended, the injury had become season-ending. Murray did not respond to my requests for an interview, but she elaborated in an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle’s Susan Slusser. “I was so excited [about supporting the Ballers],” Murray said. “But I’m not going to tolerate poor conditions for my guys.”

Murray was the first Black woman to be certified as a player agent by the MLB Players Association. She’s also married to A’s legend Dave Stewart. In the East Bay sports scene, her words carry weight, and among Ballers fans, they inspired a brief but severe crisis of confidence. (“Does anyone know what’s happening with the ballers right now?” one fan wrote in the team’s most popular Facebook group. “I’ll be heartbroken if they go under.”) On X, meanwhile, handles that had begrudged the Ballers’ cozy relationship with Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao jumped all over Murray’s tweets, proclaiming the Ballers were a scam, a “woke grift” orchestrated in concert with the mayor that was “falling apart.” Ballers fans clapped back, but in some ways, it only made the situation worse. The discourse turned dyspeptic.

In the midst of it all, Paul and Bryan regrouped at the offices of their PR firm in downtown Berkeley. Dividing Oakland was the opposite of what they had set out to do with the Ballers. But a cynical perception of the team had begun to spread; headlines were appearing in local newspapers, along with concerned segments on local news, wondering aloud whether the team was in fact the scam its critics contended. This wasn’t just a vibe shift to try to ride out, they determined, but a wound to cauterize.

As players and coaches met for a team meeting to “clear the air” and “talk about what had happened,” Paul and Bryan drafted a statement. It reiterated the Ballers’ commitment to transparency and to “build in public.” It also detailed, “in an effort to try to provide as much visibility as possible,” what mistakes Paul and Bryan understood the team made regarding player housing, player safety, and Myles Jefferson’s injury, along with what measures they were taking to remediate them. “We continue to work hard each and every day to build something great,” Paul and Bryan wrote. “We always knew there would be missteps and hard days along the way. We will never waiver in our goal: to build a winning culture and bring championship baseball back to Oakland.”

They published the statement that Friday. Then they waited. Anxiety dogged them. They’d worked for more than a year now to make their wild idea a reality, had twined their reputations, families, and fortunes to it. It all suddenly seemed at risk. Would Oaklanders continue to think of the Ballers as an aspiring community asset or write them off as a grift? An answer came that night, when the Ballers took on the Yolo High Wheelers at Raimondi Park. Fans showed up in force, and the Ballers played great, winning 13-0. The next morning, fans participated in the Ballers’ inaugural “Litter League clean up day” at Raimondi Park, which the team put on with Keep Oakland Beautiful, a local nonprofit. That afternoon, the Ballers beat the High Wheelers again, to the tune of 17-3. Leon and the 68’s were at all three events. “It was like nothing had happened,” Leon told me. Twitter, as they say, is not real life, but by Monday, even the arguments online had seemed to sputter. The Ballers fan groups warbled with gratitude for the Ballers’ “continuing commitment to investing in Oakland,” as Josh Gunter, head of Friends of Raimondi Park, put it to me. The vibes, it seemed, had shifted back, the bleeding stanched.

5.

What will become of the Ballers? It’s an open question, but for all the growing pains, it’ll come down to ticket sales. As Shapiro, the Pioneer League president, put it to me, to succeed in independent baseball, “you’ve got to be totally in love with the idea of selling hot dogs.” And the Ballers haven’t been selling a ton of hot dogs in their inaugural season. They’ve been averaging around only 1,600 a game since the Opening Day sellout. (Tickets range from $15 for bleacher seats to $32 for premium.) That isn’t horrible by indie league standards, but it’s inadequate for the Ballers’ purposes. “We need more people coming out to games,” Bryan told me one afternoon in the bleachers at Raimondi—thinking, perhaps, about the Ballers’ many expenses, which, from stadium costs to rent to player salaries, are higher than other Pioneer League teams, which tend to play in cheaper Mountain West states. “Simple as that.”

Paul and Bryan remain confident, however, that if they stay loyal to the Ballers’ initial mission—and keep working to get better at carrying it out—success will follow. “We want to be a joy factory,” Paul said. “If we’re able to do that, I’m confident that that’s going to be an economically successful business.” There’s reason to believe they’re right. Once the A’s have decamped for Sacramento, the Ballers will be the only baseball team in town. (Oakland and the Ballers are in talks now about extending the Ballers’ lease for a second and possibly third or fourth year.) And with a year’s worth of Pioneer League experience on the coaching staff and in the front office, the team will likely be even better than it is this year. (But don’t sleep on the Ballers the rest of this season. As of this writing, the Ballers are 42-30, now just two games out of a playoff spot.)

There’s also reason, I think, to hope they’re right. This is especially true if you live in the East Bay. As the Ballers grow, Paul and Bryan intend on investing further in the neighborhood their team calls home. Already, local youth leagues are using the park when the Ballers aren’t in town. Such investment is new for the area. “This is a part of Oakland where urban renewal destroyed 5,100 homes and businesses,” Councilmember Fife told me earlier in the summer. “The Ballers are reinvesting in a community that was forgotten about.”

Then there’s the benefit of baseball itself. I’ve thought about this every Ballers game I’ve gone to since Opening Day, but in particular on “Little League” night, a Friday evening in mid-June when Raimondi Park filled up with kids in multicolored uniforms and big-billed hats, tromping up and down the bleachers, collecting foul balls like Easter eggs. As it set, the sun reflected off the towers of downtown Oakland. I could smell the grass. Inevitably, I thought of my son. I remain ingloriously rankled over the fact that I won’t be able to take him to A’s games the way my dad took me and my brother. I smiled inwardly, however, at the thought of giving him this. Baseball, at root, is a balm for what ails us, a picnic in an urban garden. And though Ballers baseball is not A’s baseball—cannot be A’s baseball; will never be A’s baseball—it’s still baseball, still transportive and pretty, if a bit scrappy and homespun. (Shapiro likened Ballers games to “a street fair wrapped around a professional baseball game,” and that about covers it.)

We started this team because we were heartbroken. And we felt like this couldn’t be the end of baseball in Oakland.Bryan Carmel

And there’s real civic utility to providing access to it. Outside Raimondi Park, Oakland remains a laboratory of conflict. The FBI raided the mayor’s house in June. The city is teetering on the brink of budgetary doom. Robbery rates are rising. And, of course, off the 880, the Coliseum still sits empty and dark, issuing sorry, haunting reminders of all Oakland had recently lost, creating its own enormous, consumptive silence, a new kind of black hole. Inside Raimondi Park, however, on that June night, kids were streaming down the concourses lightly as kite strings, towing gloves and cupping hot dogs, and vendors were selling peanuts, and displays of grace ended in plumes of dust, and when the seventh inning stretch arrived, fans sang “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” wrapped around each other like frolicsome seals.

But it’s not just diversion that makes baseball worthwhile. Baseball, like all sports, is most compelling—most personally transfixing and communally annealing—when it inspires a sense of co-ownership. Growing up, my affinity for the A’s was always grounded foremost in my sense of affiliation with them. I cared about them because I was certain that, as a fan, I was not just a consumer of them—how crude!—but a collaborator with them. I fell out of love with the team when maintaining that belief became impossible.

Ballers games bring back that sense of collaboration. Before lineups are announced at Raimondi Park each night, the PA announcer ritually booms, “NO ONE IS GOING TO TELL US WE CAN’T HAVE BASEBALL IN OAKLAND,” and it registers both as a call to arms and a reaffirmation. The team is a work in progress. The comeback Paul and Bryan sought to lead with it remains incomplete. Even when it is complete, the Ballers truly will never be the A’s. But they will be ours. There’s utility to that, too.

The Ballers’ survival would also, I think, prove broadly inspiring—that is, whether you get your sports in Oakland or Portland, Savannah or the South Side of Chicago. “There’s a story to tell here about a different way to build a sports team,” Bryan told me back in May. The story is mostly about community and resilience—Bing Russell, who told the same story 50 years ago, called it “a version of the American dream”—but a year now into following the Ballers, I’m convinced it’s also about agency. Before first pitch on Opening Day, Paul and Bryan took the field to address the crowd. “We started this team because we were heartbroken,” Bryan told the crowd. “And we felt like this couldn’t be the end of baseball in Oakland.” Then a picture of a young boy in a Little League uniform flashed on the scoreboard in right field. It was Bobby. Bryan introduced him and dedicated the evening to him—just as he and Paul had hoped they would months prior.

When it was Paul’s turn to speak, he didn’t say much—instead, he immediately asked the crowd to humor him with a Let’s go, Oakland chant, as if he just couldn’t wait. The crowd responded as if they couldn’t wait either, and it got very loud. Later, however, in the bottom of the first, designated hitter Dondrei Hubbard smashed a two-run homer over the wall in left field. The ball flew over a crew of firefighters watching the game from atop their truck behind the fence and crashed through the window of the red-brick warehouse that faces the park. Everyone, firefighters included, lost their shit. Then a Let’s go, Oakland chant started up again, this time on its own, and it rattled the night.

Dan Moore is a contributor to The Ringer. His work has recently appeared in The Atlantic, San Francisco Chronicle, and Baseball Prospectus. He’s a nominee for the 2024 Dan Jenkins Medal for Excellence in Sportswriting. Follow him on Twitter @DmoWriter or at www.danmoorewriter.com.