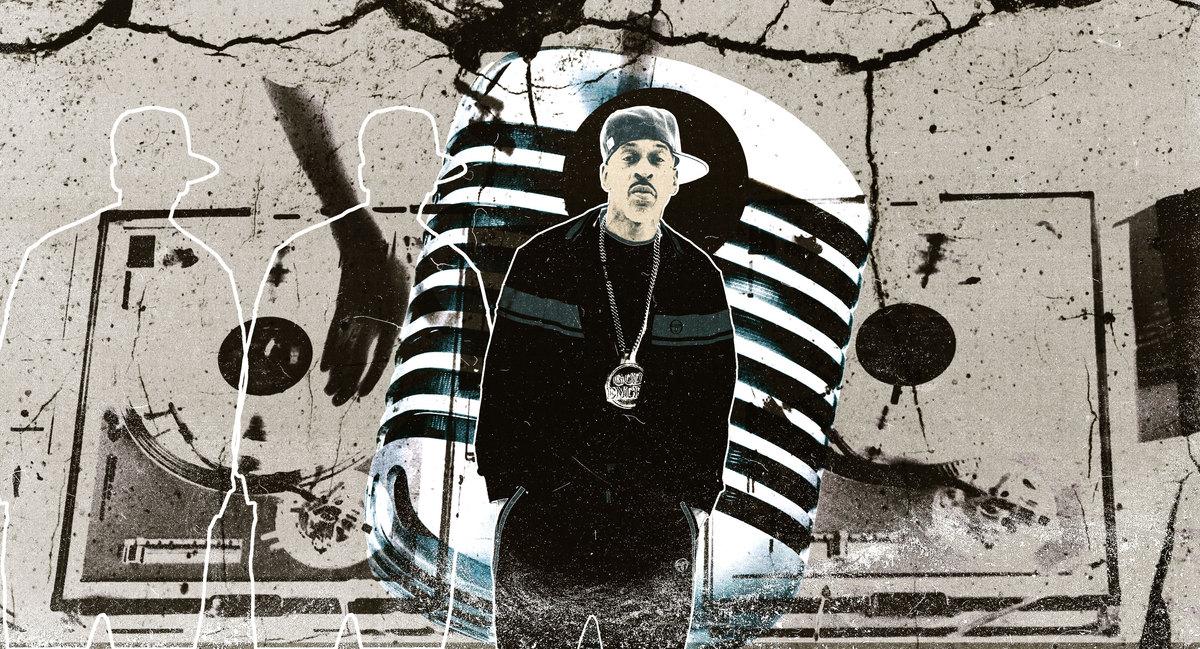

The Word of God: An Interview With Rakim

The most influential MC of rap’s golden age discusses his craft, his origins and influences, and hip-hop’s place in historyHip-hop in the 1970s and ’80s was under attack on multiple fronts. One cadre of aggressors was the political and religious leaders lobbing accusations of moral turpitude and seeking remedy through censorship—as if Black teenagers had smuggled violence, materialism, and misogyny into a heretofore unsullied America through this vile, nascent subculture. The other set of antagonists was the music critics, radio program directors, jazz neocons, and sundry gatekeepers of the culture’s citadels who maintained that rap was not music, graffiti was not art, and sampling was merely theft and who deemed it all unworthy of the airwaves and the arts sections, to say nothing of the classrooms and museums. It’s worth noting how many of those same motherfuckers showed up last year to celebrate hip-hop at 50, with nary an apology tendered.

In the heat of those culture wars, hip-hop needed two things as it scrapped for the right to exist: credentialed defenders and representative geniuses. When New York City declared “war” on graffiti and vilified its practitioners as sociopaths, The Village Voice’s Richard Goldstein looked at subway cars adorned with masterpieces by PHASE 2 and RIFF 170 and clapped back that these artists seemed like the healthiest and most assertive people in their neighborhoods. When Melle Mel dropped the social-realist dispatch that was “The Message” in 1982, he became the representative genius who handed rock scribes the rappers-are-reporters argument that would be marshaled on behalf of everyone from Schoolly D to N.W.A by the decade’s end.

But it wasn’t until Rakim Allah—born William Michael Griffin Jr.—came along four years later that hip-hop’s defenders found a representative behind whose banner they could storm those citadels of culture and end any arguments about whether this new thing was art with the finality of a sword through the chest.

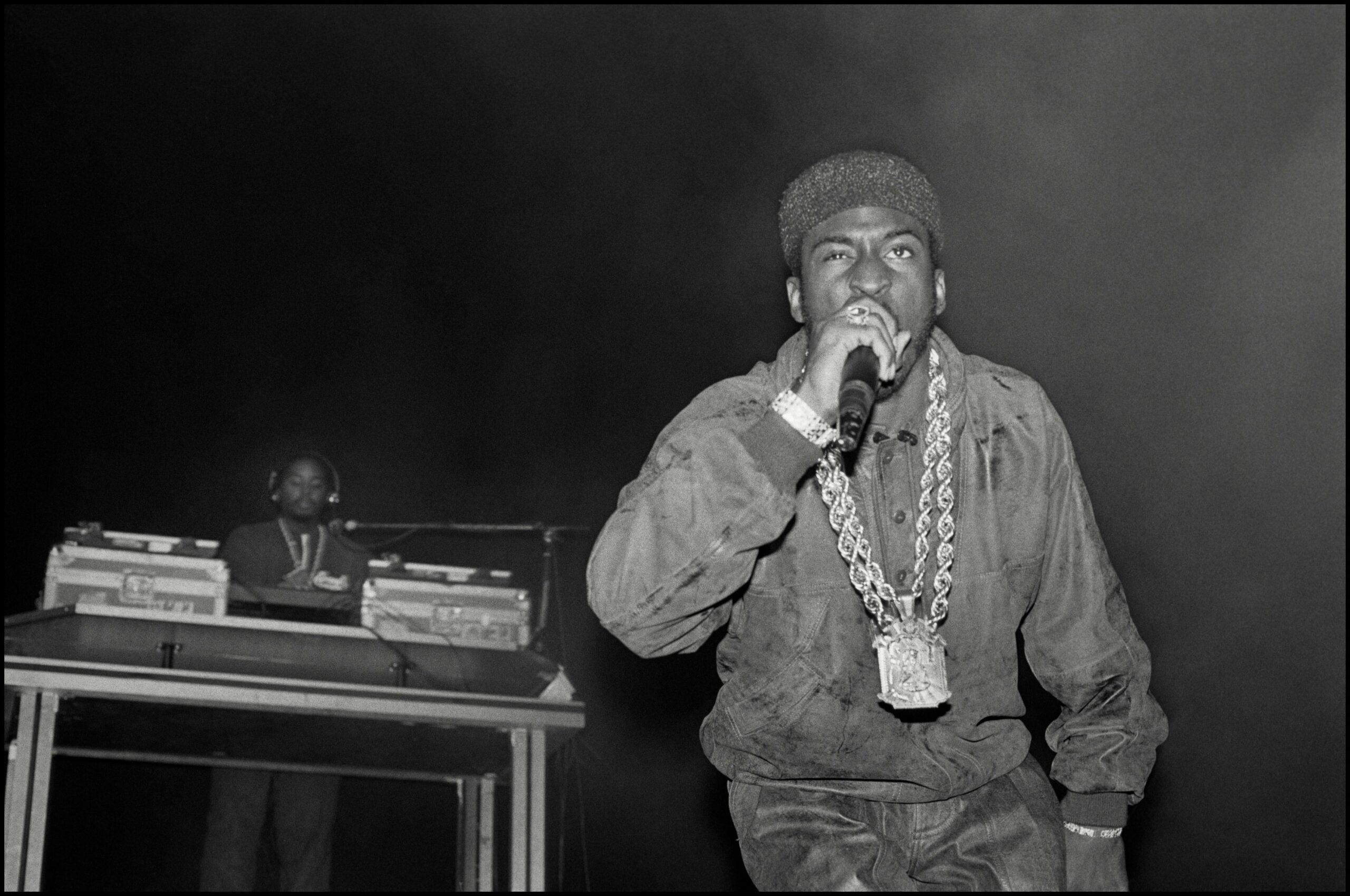

The class of 1986-87 changed hip-hop, and Rakim was its valedictorian. That emergent cohort—Eric B. & Rakim, Boogie Down Productions, Big Daddy Kane, Kool G Rap & DJ Polo, Ultramagnetic MCs, Biz Markie, and Public Enemy—pulled hip-hop out of a lurching transitional period and into a golden era, with a new sample-based aesthetic that provided thrilling sound beds for lyrics of astonishing dexterity, intensity, and complexity. But Rakim stood apart, even from the titans with whom he rode in.

You could start with the vocal tone. Chuck D rapped in a booming stentorian bass that hinted at his past as a radio jock; Big Daddy Kane studied James Brown stage videos and unfurled lyrical fusillades with the same exactitude the J.B.’s applied to their horn stabs; KRS-One wanted nothing more than to be hip-hop’s Super Cat, the Don Gorgon of the dancehall. Rakim rapped and wrote from a place of deep calm, a locus of furious precision that belied his youth and suggested reservoirs of wisdom and a preternatural ability to distill it into a meter that was both seamless and staccato, syllabically dense and syncopated but pocked with breathtaking instants of negative space. He was the only one you could imagine rhyming onstage at a jazz club, dropping knowledge over an upright bass, embodying the difference between mellow and slow burn.

In an era of declarative statements—KRS-One, for example, opened his first three albums by serially demanding that the listener recognize him as a poet, a philosopher, and a metaphysician—Rakim was posing unanswerable questions: “In this journey, you’re the journal, I’m the journalist / Am I eternal or an eternalist?,” a couplet that reversed the polarity of the rapper-reporter trope and inspired writer Greg Tate to compare him to Roland Barthes and paint him as a “poet pondering whether he is a modernist or a postmodernist, a creative God or a revised body of texts.”

We could talk about enjambment and imagery or gold rope chains and Dapper Dan suits, discuss Ra’s deep musical pedigree and legendary elusiveness; we could cite dozens of lines turned aphorisms, burned into the universal hip-hop consciousness. But on the most essential level, Rakim’s ethos is simply mastery. On song after song, he glides effortlessly through physical environments and mental planes alike, equally cosmopolitan and astral, unsmiling but never off-balance. He brought abstraction to hip-hop in a way that felt both grounded—in the Islamic teachings of the Nation of Gods and Earths, in Egyptology, in detailed observations of New York City life—and ethereal. It’s become a cliché to say that the game of basketball slows down for the great players, but if hip-hop didn’t slow down for Rakim, maybe he slowed down for it.

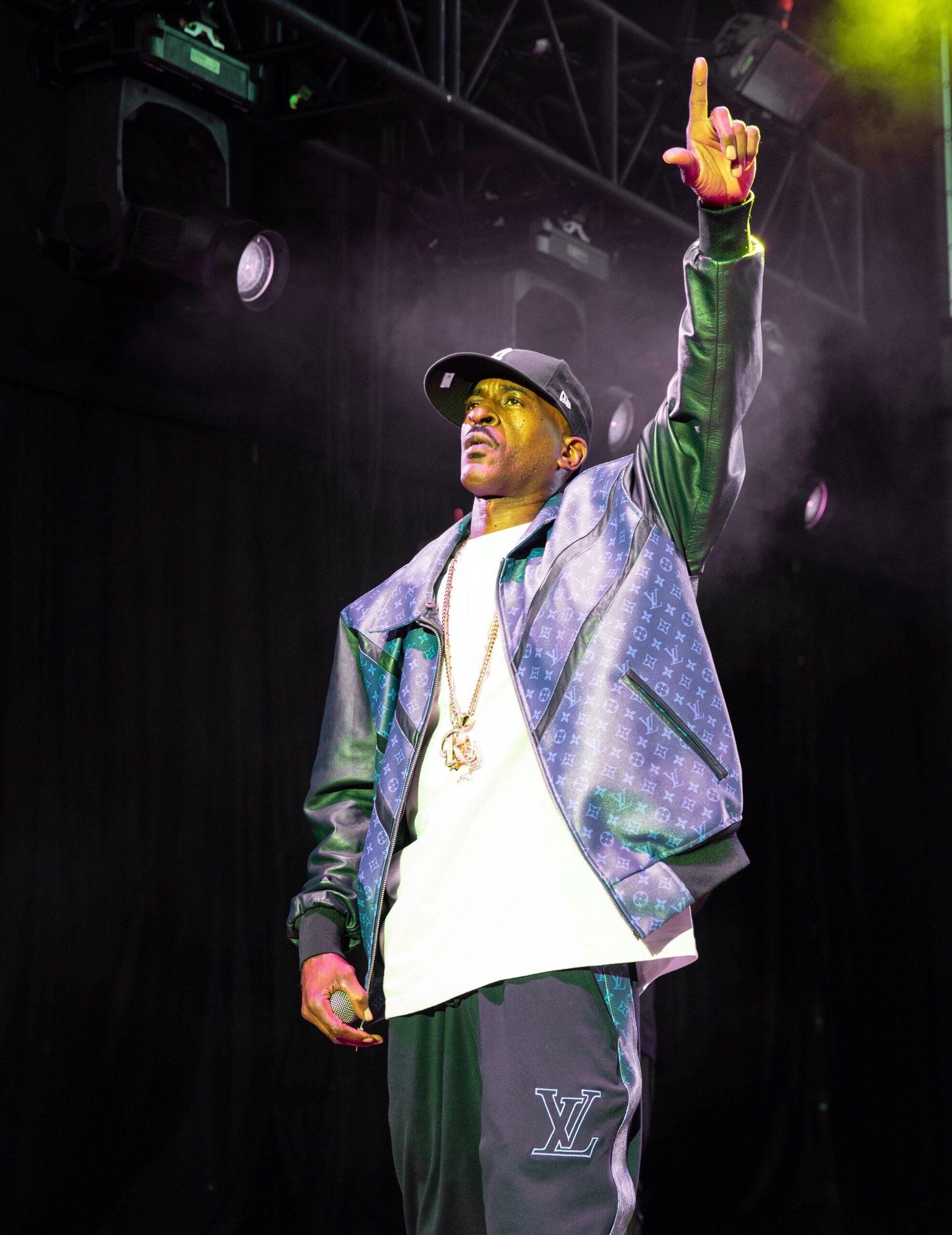

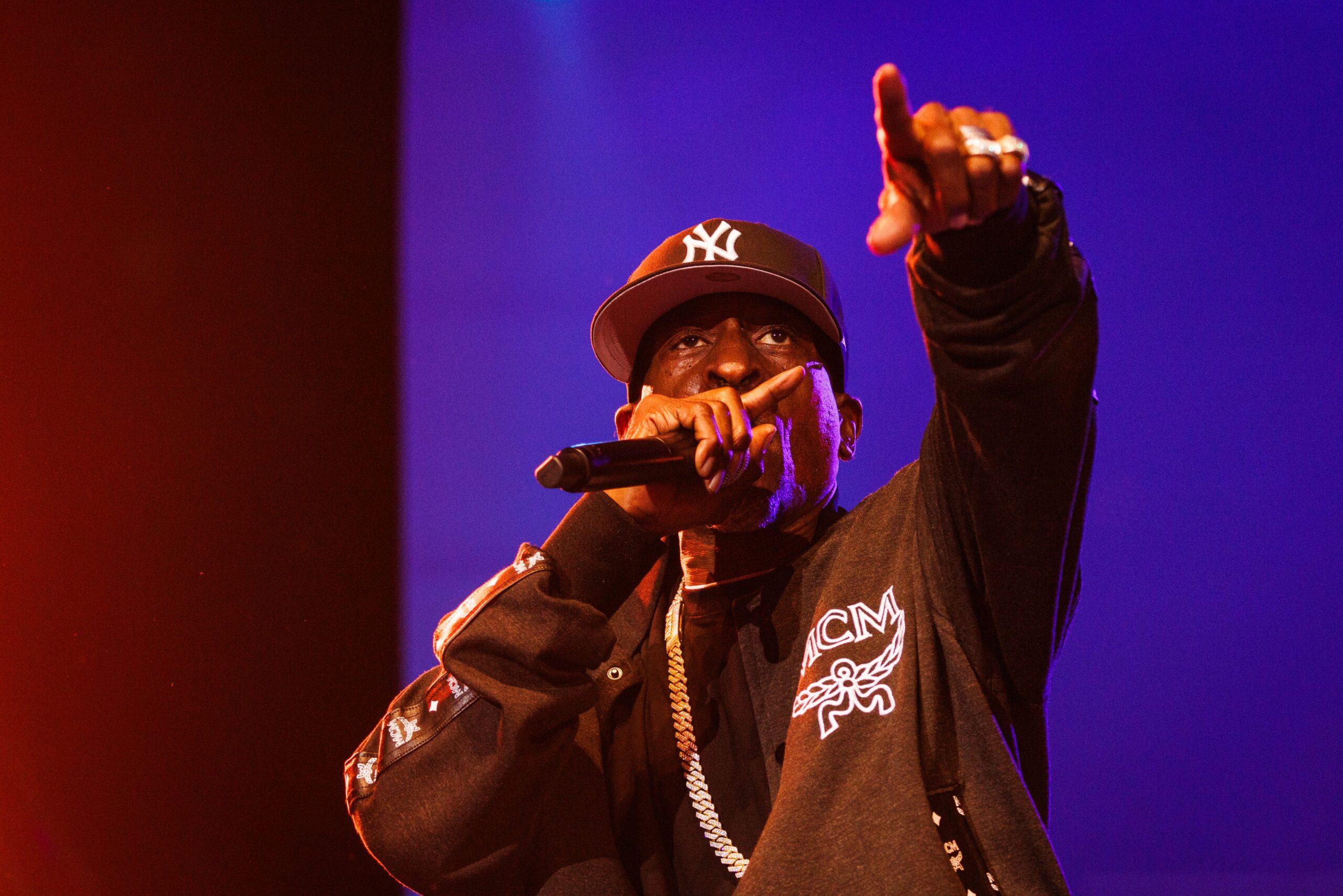

Rap has undoubtedly changed since Rakim’s last effort, The Seventh Seal, a 2009 offering with him at the forefront and producers like Jake One and Nick Wiz orbiting the venerated MC. This year, Rakim reemerged with his fourth official solo project, G.O.D.’s Network: Reb7rth, a compact effort peppered with guests throughout, from lesser knowns to living legends, as well as a long list of the dearly departed—DMX, Fred the Godson, Nipsey Hussle, and Chino XL. The guest list speaks to Rakim’s reach and generational influence. G.O.D.’s Network differs from Rakim’s past work in that he not only raps, but also made the lion’s share of the beats, also incorporating all scratches and cuts himself, a showcase of his triple-threat status alongside his renowned lyrical prowess. This is a critical juncture for the God MC, who supposedly has another one coming, an official fifth solo project, a proposed return to form centered more on the iconic rhymes and writing that made his work fabled to begin with.

Here, Rakim opens up about his childhood, his parents and siblings, and coming of age when hip-hop was young, unpacking his writing process and how a dutiful fixation with words informed his illustrious songwriting and career.

Walk us through your writing process. What do you draw from, and how do you apply it to music?

Early on, I learned how to think like a writer, meaning all day, every time I see a phrase or sign or anything, I’d hold on to important words that stood out. I’m always absorbing and trying to figure out different rhyme schemes. I write notes down on the side of the margins while I’m putting verses together. That way, I won’t get sidetracked and can focus on what I’m writing that moment.

When it’s time to record, I have premeditated rhymes. And I’ll add words as I write along to the music. Sometimes the music tells me what to write. If the music has feeling, it gives me visions, and my head starts spinning, especially if the sample grabs me. Then, thoughts come [to me] in different rhythms. When I’m in the zone, when all the phrases and all the information starts coming, it’s hard to stop it. I hear concepts right away, and words are flowing. I also pay attention to the different rhythms of the words. That’s why I write those sidenotes, so I can come back to them later. It’s a pretty organic process, I would say.

The first rap song I heard was in my basement with my brother and his friend. ... I’ll never forget, the record they played was “King Tim III” by Fatback Band. I knew then and there I was ready for this new type of music.Rakim

What subjects did you gravitate towards in school? Were you always into words and writing?

It’s funny you ask because early on, in high school, I liked social studies and science the most. Then one day, I cut class after lunch, and my English teacher saw me hanging out. She had seen me in the talent show earlier and said, “You rap, right?” I said, “Yes,” and she responded, “Aren’t you supposed to be in my class?” She said that and just walked away. It mattered to me that my English teacher recognized me rapping, and it occurred to me that English should be my focus if I’m trying to be a rapper.

From then on, I started thinking about words—how to construct them and how to properly use them. I took an interest in vocabulary. I learned how to write a book report. Book reports have all the elements you need to put into your rhymes. I began taking English very seriously, and I owe Ms. Thompson, who later changed her name to Ms. Bonaparte, for so much. Her class helped me become the writer I am.

Early tapes exist where you refer to yourself as “Kid Wizard,” and even then it seemed like your rhymes were already advanced. What were the reasons behind the name? That must’ve been early on.

Kid Wizard was my alter ego growing up. I always knew I would be a clever writer or rhymer when I got older. The name fit because, at the time, I was still very young. I remember in the fourth or fifth grade, I went to the park and saw rappers out there. I felt young, but you don’t realize how young you truly are until you try.

So I went over and grabbed the mic, and they all laughed at me. Someone yelled: “Somebody come get this little dude!” [Laughs] I felt Kid Wizard fit because I was always aware that I was a kid trying to get into the business of those who were older than me. So as I got a little older and really got into rapping, I kept Kid Wizard for a while before changing it to Rakim.

Being from Long Island, you were New York adjacent. Aside from those rappers in the park, how did the culture reach you?

Yeah, being all the way out in Long Island, we were on the outside looking in. It was harder to get access to a lot of things. I was into collecting tapes. And rap tapes, especially, were extra hard to get because they were just live recordings from the park. These brothers were recording their shows, and only a select few in the city would even have them. You had to know somebody.

I also was lucky to have older brothers and sisters. I lived vicariously through them as they were growing and absorbing life. They would bring what they learned into the house. My brother Stevie was a little older and at the perfect age around when hip-hop first came out. And he was on top of it. His friends in the neighborhood were also really into it.

How was it like seeing everything develop around you? What did that feel like?

I remember hearing DJs in the park, playing disco and other records that appealed to a younger crowd. My moms and pops played Kool & the Gang around the house, so when hip-hop got popular, it felt like music was young again. Not only that, but it was young people who were learning to use the music.

My brother was friends with some DJs who lived in the area, so they would come perform at neighborhood parties and sometimes leave their equipment at our house. Sometimes they’d leave it over for a few days. And I was always front and center to see what was going on.

Do you remember the first rap record you came across?

The first rap song I heard was in my basement with my brother and his friend, this dude who went by DJ Maniack. Hip-hop was young, so to hear it on wax was mind-blowing. He brought his equipment over, and the whole time as he was setting up, he was telling my brother, “Wait till you hear this.” I’m just sitting there intrigued. I’ll never forget, the record they played was “King Tim III” by Fatback Band. I knew then and there I was ready for this new type of music.

You mentioned that the music can sometimes guide your writing. What do you make of those early songs with Eric B.?

Well, in the early days, I was just rhyming off stuff that was already played at the park or stuff I heard at basement parties and gymnasiums. By the time I worked with Eric, I just brought all of my experience into the studio. For example, for the track “Paid in Full,” we used that Dennis Edwards bass line on the beginning part. Well, when I was younger, I had already written an entire routine to that record. So these were beats that I rhymed to all the time, because I grew up in the breakbeat era. I always liked lots of breaks, and horn sections, too. I had a lot of influence on those beats.

There’s uncertainty surrounding the production on some of that early Eric B. & Rakim material. Is it more accurate to say those songs are coproduced?

Yes, because in those early days, Eric B. & Rakim were really a group. People just expected Eric on the beats and me to rap. But those songs were a group effort. We left it as “He’s the producer” and “I’m the rapper” because we thought it’d help the brand. We thought that was what people wanted and just wanted to live up to expectations. At the time, I didn’t care. I didn’t think it was important to tell people I did a lot of those beats.

I was basically making beats to drive my writing. I also realized later on that some of those records I sampled, the ones nobody else sampled, are some of the beats that brought the best out of me. People assumed Eric did all the production just because he was the group’s DJ. It never bothered me, but as time went on, when everybody was crediting Eric with all the production, I started letting people know I did a lot of those beats myself.

What comes to mind when looking back on those first albums?

Well, I was sometimes biased, and that was a problem. I thought about this recently. I wanted to make these songs my way, and I didn’t care if it appealed to everybody. I only cared about being a true creator. At the end of the day, I wouldn’t change a thing because what I’ve done has allowed me to get this far. But it was a few years ago that I realized I didn’t make popular music for the masses.

Did you ever get writer’s block or have a hard time coming up with ideas?

It can get complicated because I second-guess myself on a lot of things I think and say. So yeah, sometimes I do [get writer’s block]. I might come up with a bar or four bars. But then I’ll sit there and look at it, turn it upside down, turn it backward, look at it from different angles, rewrite it, then rewrite and change it again. And sometimes you just go right back to the first thing you wrote [laughs].

Grandmaster Caz, Melle Mel, and Kool Moe Dee are my Mount Rushmore. These MCs and their words and phrases sent me on my way.Rakim

At what point did you know people were starting to notice your delivery and rhymes?

Not until way after the first album came out. It wasn’t until we were about to do the new album did I get any feedback. I didn’t even know people dug the first album until we started the second one. We were just grinding. One day, someone called my writing “complicated,” and that stuck with me. They also told me I was going over people’s heads. And they meant it in a positive way, like they were giving me flowers, but it made me rethink everything. As modestly as I reacted, it still affected me, like, “Am I confusing the audience?”

I just always wanted to push the envelope, know what I mean? I wanted to rap with clarity and have them understand the words. I would even reiterate certain phrases on the next album just so I could make my point clearer, because I now understood that some didn’t understand my lyrics the first time. I wanted to put forth my ideas but didn’t want to be over anyone’s head. So I owned it. I even considered rhyming and writing differently on the new album, but I stopped myself. I have to own who I am, and this is what I do, so I just had to be myself.

Many consider you the most important rapper because your writing and style spawned so many MCs afterward. Which rappers made the biggest impression on you?

Grandmaster Caz, Melle Mel, and Kool Moe Dee are my Mount Rushmore. These MCs and their words and phrases sent me on my way. These brothers didn’t have the internet to watch videos to learn from or mimic others doing it. No MTV or VH1. None of them had anyone to shape and mold them. They did this with their bare hands.

There were a bunch of crews in New York, and they were all dope. But out of all of them, Melle Mel was there first [to me], and he was the dopest. Even early on, he was so prolific. He once said: “A child is born with no state of mind / blind to the ways of mankind / God is smiling on you, but he’s frownin’ too / Because only God knows what you’ll go through.” That’s timeless right there, and he rapped that in the early ’80s. He emerged really early on, and I always wondered who he was influenced by. Where did he get his style from? Later, I realized he simply got it from himself.

Clearly, you took the craft very seriously. How was it making earnest, intelligent music when rap was still being treated as a novelty?

It was frustrating, for sure. When I was mad young, one time I asked for DJ equipment for Christmas. Even though my moms and pops knew I was really passionate about hip-hop, they still said no. I also realized that my parents weren’t rich that day. My mom shot me down even after I told her how I’d use the equipment and that I’d take it very seriously. She asked, “Even if I buy you this stuff, how you gonna play records with no electricity? Listen, if I spend all my money on this, we won’t be able to pay the bills.” I just sat there stupid.

Even later, when things were picking up for me as a rapper and my parents saw that I was putting things to the side because I was taking this very seriously, they still questioned hip-hop. I was writing rhymes one day, and my mom was like, “This ain’t gonna last!” I’m naturally defensive about what I’m passionate about, so that hit me like a ton of bricks. In the back of my mind, I wanted to prove them wrong and was hoping hip-hop as a whole would also prove them wrong.

The media was the same way. I’d hear the same question when I was being interviewed: “Do you think hip-hop is a fad? Do you think it’s going to last?” And I used to always say, “Hip-hop is young right now but is growing, and one day it’s going to be a real genre.” All music that is taken seriously was placed into genres—rock, R&B, or jazz, for example. They used to just call rap “thug music” or “hood music.” It wasn’t even considered a musical genre yet. I was always optimistic that the music would supersede the negative stereotypes and all that negative energy.

Is all the negativity why you’ve kept your writing pretty much positive?

The no. 1 reason I kept things positive was my moms and pops. I felt obligated to show them what I learned because they were so involved with me learning about music. They played the best music in the world and were passionate about it. When they wanted to relax, they played music. When we had company, they played music. I remember Anita Baker dropped an album, and my father went out that day to get it and blasted it all day [laughs]. So when I first started doing music, I knew when I got home, I was gonna go to the basement and put a tape of my music on, and they’d be the first ones who’d hear it. So I had to keep it respectful.

So when we did that first record, I made sure there was no cursing. I just wanted to impress my folks first. I just wanted to let them know that I understood. I was getting deeper into my career and deeper into Islam. I just knew that this was the way to speak. Even though my moms and pops have been gone for a while, I still do things sometimes and hope for their approval.

You mentioned Islam, and I want to discuss it a bit. Does religion inform your writing?

Well, it makes me very conscious of what I say. There are pros and cons to everything, so I weigh my words. I think about how it affects different people when they hear it. Islam has also taught me to analyze my work and make sure that it’s official. Sometimes I might come up with something, and then I might have to pull out the Bible, the Koran, the Torah, and a whole bunch of literature to make sure that what I’m saying is correct, know what I mean?

I didn’t want to rely on cursing to fill up space in my songs. I also don’t have to deal with flak from what I say. And if I did say something controversial, I’d make sure I could back up what I wrote with facts. I wouldn’t change this approach because it made me a better writer and MC.

Earlier you mentioned Melle Mel’s style and Kool Moe Dee’s style. Many cite your writing as being most influential. How would you define your style?

The best way I can explain my style is to explain where it came from—jazz. Listening to jazz growing up, I learned the difference between time and space. Hip-hop’s time signature is four-four. So it’s like, “1-2-3-4, 2-2-3-4, 3-3-4-4,” and so forth. To me, that’s simple. But jazz is very complicated because of the many different time signatures. Ninety-eight percent of hip-hop is four-four. Now and then an artist will switch it up, but rarely.

When I started writing rhymes, I had an internal clock that kept interfering with the songs we were making. It was because I listened to all this different jazz and I was reading and playing music early on, so I really grasped the concept of timing. In the beginning, I would write rhymes but not understand this other metronome that was playing in my head because it wasn’t in four-four time. I realized I was putting a lot of words into my rhymes, sometimes too many. I was utilizing as much time and space as I could and not thinking when the bar ended. I was more concerned with how many words could I fit into a measure.

One day I was listening to music in my mother’s basement. This is, like, 1985. She played this John Coltrane record, and it was rocking while never playing the same melody twice. Pretty sure Coltrane soloed the whole record. When I heard that, I said to myself, “I’m never gonna use the same cadence in one show. I’m going to switch it up, like a jazz musician.” I was using different syllables and words and putting them in different places on the beat. I also noticed jazz had no vocals but was able to make you feel the way the song wanted you to feel. So I’d say my style is based on being similar to that of a jazz soloist.

Last, longtime listeners of hip-hop who understand its development consider you utmost consequential. What are your thoughts on current hip-hop, and what do you make of your place in its history? Would you agree you’ve made the biggest difference?

Today, you can’t do anything without hip-hop. It’s taken over. It’s not only a genre, but it’s the biggest genre. And other genres now use hip-hop. Hip-hop has always sampled others, and now it seems like other genres use hip-hop. As for me, I’m modest. I enjoy being a lifelong student of everything I do. I also know how I got here and what my claim to fame is. It’s my gift with words. So yeah, sometimes my ego tells me [laughs] that I’m the baddest brother to ever touch the mic. The main thing I ever wanted to do as a writer is to connect with the people. After all these years, it seems like I was able to do that.

David Ma is a veteran music journalist of more than 20 years whose work appears in Wax Poetics, NPR, Rolling Stone, The Guardian, The Source, The Paris Review, and many others. He teaches a course on hip-hop history and its global impact at San Jose State University and is also part owner of independent record label Needle to the Groove. He cohosts Dad Bod Rap Pod and is the lead editor of Dust & Grooves, Volume 2. He is currently working on his first book and writes from the Bay Area.

Adam Mansbach is the author of the no. 1 New York Times bestseller Go the Fuck to Sleep, as well as the novels The Golem of Brooklyn, Rage is Back, The End of the Jews (winner of the California Book Award), Angry Black White Boy; the memoir in verse I Had a Brother Once; and the acclaimed Netflix Original film Barry. His work has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Esquire, The Believer, and The Guardian and on All Things Considered, The Moth Radio Hour, and This American Life.