It’s quite the image: the Union Jack swirling down the toilet. The artwork of the first Oasis demo cassette, like other beloved artifacts of Britpop, means something different depending on whom you trust.

For Alan McGee, the Creation Records founder who signed Oasis on a whim, convinced that they would be the biggest band in the world, this artwork captured a feeling of a new decade’s promise. Margaret Thatcher was out, U.K. rave was slowing down—Parliament’s infamous Criminal Justice and Public Order Act was only a year away—and something traditional about long-repressed Britain was swirling into something new and exciting and vaguely psychedelic. The post-rave generation was ready for the next party. The future was in McGee’s hands. Now he could sell it.

Not so fast, thought Noel Gallagher. His graphic-artist-in-training friend volunteered to design his band’s cassette. It was based on the U.K. flag painted onto Gallagher’s rehearsal room wall just to the right of a Beatles poster. Gallagher just thought the cover looked cool. It was something the Jam and the Who would do. He had to clarify to McGee that his cassette was not promoting the National Front—not the first or last time someone accused Britpop of bubblegum fascism.

McGee and Gallagher at least agreed that the Union Jack swirl was perfect. Once again, presentation trumped intent. Style won out over politics and metaphors. The duo’s next collaboration would be the ultimate twist on the rock ’n’ roll fantasies of Gallagher’s youth: Definitely Maybe. Britpop, already a dirty word, had found its new, unwilling champions, and it was bigger than ever. It’s been misunderstood ever since.

Oasis’s debut LP—which turns 30 on Thursday, two days after the band announced a reunion tour—didn’t invent Britpop. By 1994, Britpop had already gifted us its earliest masterpieces, including Suede’s 1993 self-titled debut, which indulged in witchy, Bowie horniness, and the Kinks-like character studies of Blur’s Modern Life Is Rubbish and Parklife. The latter was notable. Damon Albarn and Co.’s first grand achievement was a Born in the U.S.A.–esque blockbuster of English guitar rock, its jubilee glee distracting most listeners from lyrics about young people at the end of history, over-drugged, lacking opportunity, and realizing that modernity was nothing special. Albarn’s mission statement: to write intelligent music that could compete with Garth Brooks. More British masterpieces, some of which did compete with Brooks, were to come. Yet Oasis’s Definitely Maybe, with its own melancholy but lacking irony or self-consciousness, marked the moment Britpop became more than just a London fascination and something more universal.

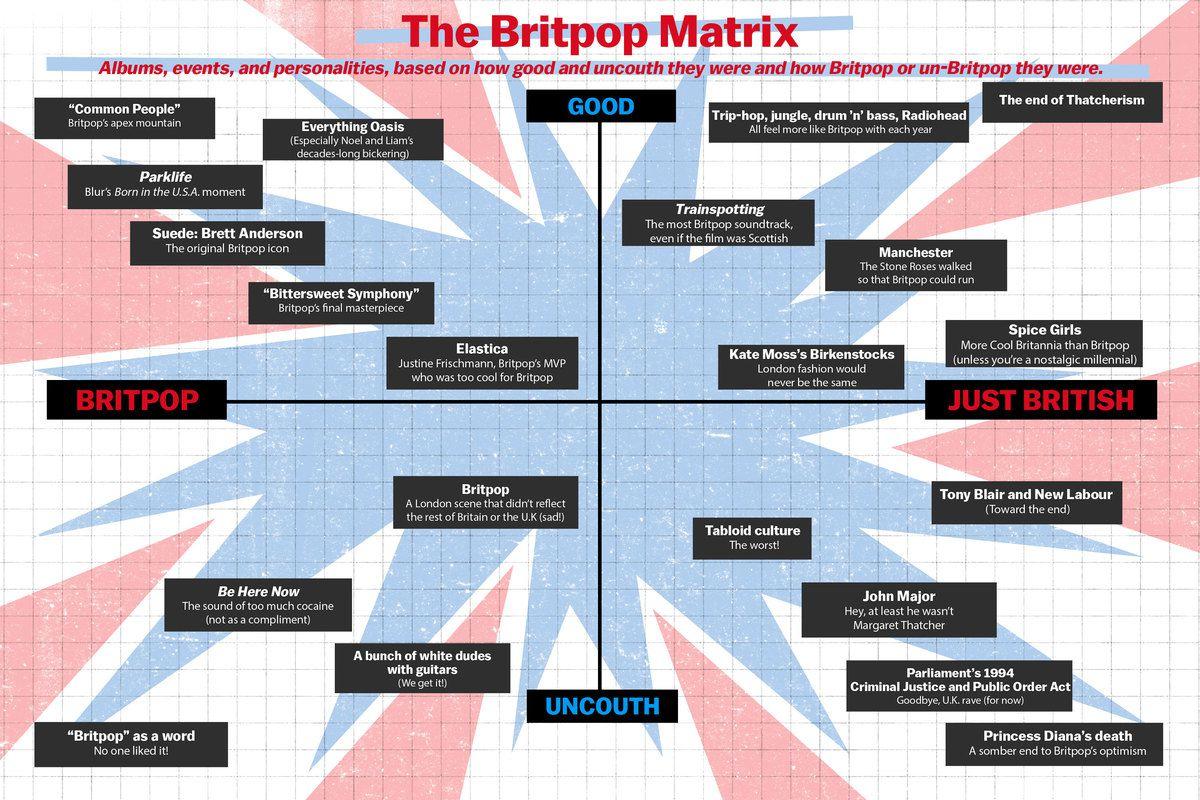

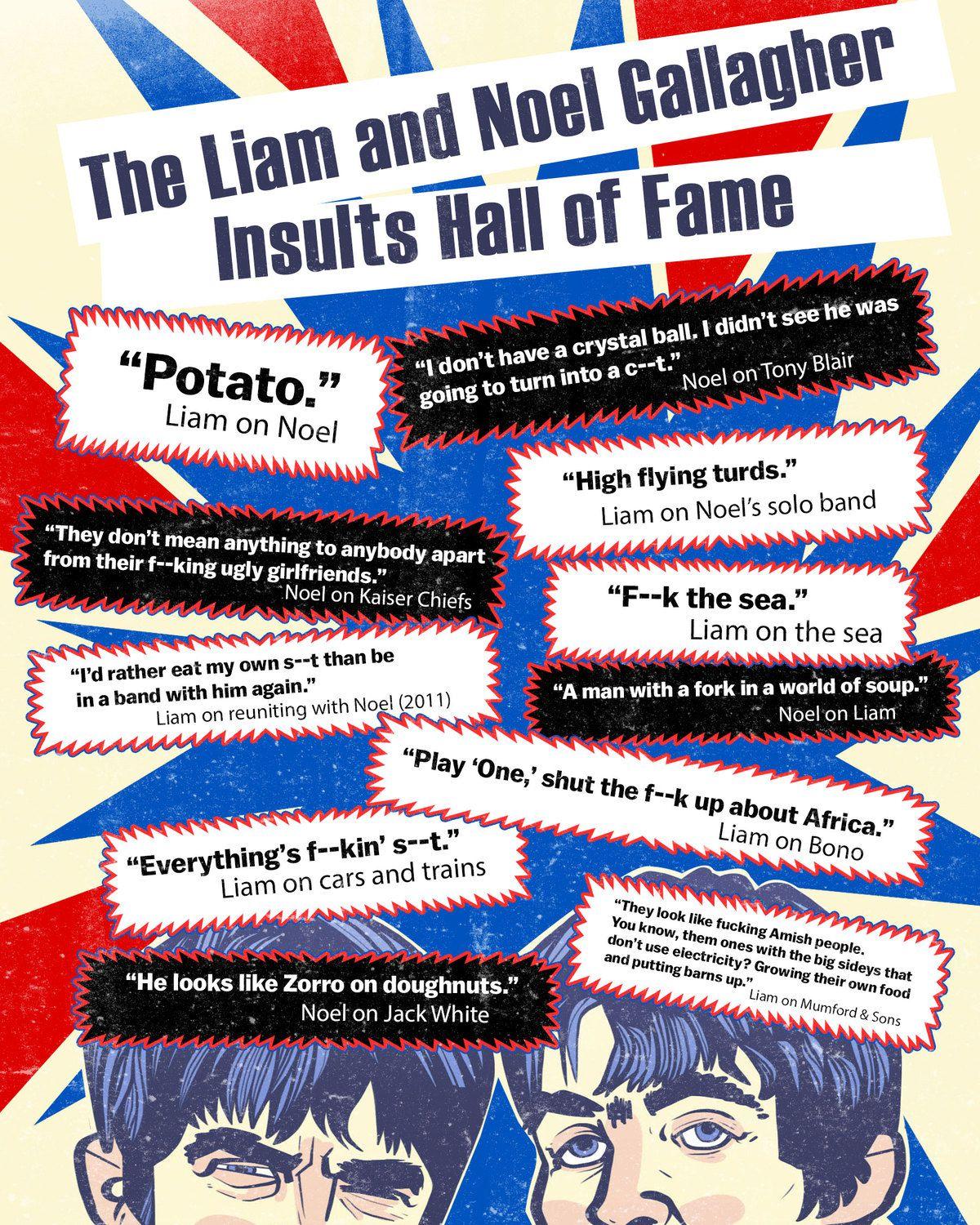

McGee was right. Oasis did become the biggest band in the world. Its time in the sun was finite, like the era it helped popularize—which in the following decades has seen its reputation go down that same Union Jack toilet. Was Britpop’s laddish culture full of piggish sexism and casual racism? (Yes, but not in the beginning.) Did Britpop open the doors to Brexit? (Probably not.) Did the media’s near-exclusive emphasis on guitar rock diminish the potential of jungle and drum ’n’ bass? (Possibly.) Is there anyone who likes Be Here Now? (There are dozens of us.) All the people I interviewed to look back on Britpop in honor of Definitely Maybe’s anniversary—many of whom are the journalists, editors, photographers, publicists, and record label heads who helped shape Britpop—have conflicted feelings about what the era accomplished. Most would agree that it was a special time to be a musician and a music fan.

Not a single human would ever have answered the question ‘What’s your band like?’ with ‘It’s a Britpop band.’Chloe Walsh

But Britpop’s reputation may have turned a corner in 2024. This year, Dua Lipa, Kendrick Lamar, Charli XCX, A. G. Cook, and more have explicitly evoked Britpop’s style, symbolism, and, most crucially, optimism. This summer, the U.K.’s Labour Party won its biggest general election victory since Tony Blair, whose calculated alignment with Cool Britannia turned Britpop into the soundtrack of New Labour, to the dismay of the scene’s original pioneers. Younger artists are also embracing Britpop, most visibly British jungle producer Nia Archives on her breakout debut LP, which is full of Union Jack iconography.

“They’re saying Cool Britannia is back,” wrote Maddy Mussen for The Standard on Archives and the Union Jack comeback, “but the faces of this wave don’t look like Liam Gallagher, David Beckham or Geri Halliwell. They’re Jude Bellingham and Bukayo Saka, Little Simz and Olivia Dean. They’re Rina Sawayama, Charli XCX, Maya Jama, Stormzy.”

Even the news of an Oasis reunion has been well received, as were last year’s Pulp and Blur reunion shows, less out of patriotism and more from a yearning for the best music, like Definitely Maybe, that came out of guitar rock’s last fruitful and creative peak in the global mainstream. Maybe the answer is even more simple: After the past few years of sleepy, sterile COVID pop, maybe we’re just craving messy, anthemic popular music again.

Yes, Blur did bomb at Coachella. Yes, Blur is not beloved by the cool TikTok teens, even if those same teens love Gorillaz and don’t realize they have the same frontman. Yet maybe 26-year-old Albarn would have laughed at the irony of one day reaching America’s biggest festival stage and getting booed because its audience had trouble understanding “Girls & Boys” or had never heard of Phil Daniels or Martin Amis. Maybe that was the point all along. Even beyond the typical cycles of nostalgia, maybe Britpop—or this new theory of Britpop—has finally conquered America, three decades too late.

One thing that’s stayed the same for the past 30 years: No one likes the word “Britpop.”

“Not a single human would ever have answered the question ‘What’s your band like?’ with ‘It’s a Britpop band,’” says Chloe Walsh, a founding partner at the Oriel PR agency who worked as a press agent throughout the Britpop years. She was at Creation Records when McGee signed Oasis. “[These bands] all saw themselves as very distinct and didn’t want to be lumped together under any kind of catchall term.” That seems to be a consensus among musicians, observers, and people interviewed for this piece: Britpop as a genre never made sense. Its origins are also more complex.

People weren’t starting bands because Britain was great and they wanted to shout about it. They were starting bands because the Tories had created an economic disaster for the working class.Walsh

Britpop lasted from approximately 1993 to 1997 and marked a new golden era of U.K. popular culture, especially in sports, fashion, and music. Though the mid-’90s marked the rise of Blair and New Labour, Britpop technically happened under John Major, the mild-mannered Conservative prime minister who had to pick up his party’s pieces after Thatcher’s 1990 resignation. In the backdrop of this turbulent power exchange was the 1989 collapse of the Berlin Wall, after which London became the first major Western capital to hint at what post–Cold War culture could look like in Europe, free of the literal and figurative divides between its people. Ironic that the music of this new future overtly invoked London’s last pre-Wall era of grand self-celebration: the Swinging Sixties. Except now Manchester’s Stone Roses were mixing U.K. rave ecstasy (figuratively and literally) with arena rock at Spike Island, New Order’s “World in Motion” was soundtracking Italia ’90 as England made it to the World Cup semifinals for the first time since the ’60s, and Croydon-born Kate Moss was shocking the fashion world by wearing Birkenstocks in The Face. Something had changed. Suddenly, after a decade of Thatcherism, it felt cool—it felt freeing—to be British again.

This something led to Select’s famous April 1993 “Yanks Go Home!” issue, featuring Suede’s Brett Anderson seductively posing in front of the Union Jack, added in without his knowledge, and a lede declaring that “we”—Select readers, Britons, people who were sick of Nirvana—could not lose the Battle for Britain to the Americans and their boring grunge bands. (Meanwhile, Kurt Cobain apparently liked Blur.) Britpop was thus “born,” even if Select did not use the term. (The May 1994 issue of The Face would include the mainstream introduction of “Brit pop”; a few months later, The Guardian declared that “We are in the middle of a Britpop renaissance.”)

The featured bands from the “Yanks Go Home!” issue were not happy that their music was reduced to fall under some dubious umbrella. They didn’t sound too alike either, from the dance posh of Saint Etienne, who dressed and sang like Sixties Swingers if they had discovered drum machines, to the post-rock glitter glam of Denim and the art pop of the Auteurs. It didn’t matter. The battle was on. Young folks were ready to fight, for good reason.

“Thatcher had waged an outright war on young people,” says Walsh, “targeting them specifically with her policies on unemployment benefits, the poll tax, and student loans. People weren’t starting bands because Britain was great and they wanted to shout about it. They were starting bands because the Tories had created an economic disaster for the working class. There was no upward mobility, so football and pop stardom seemed like they might be creditable ways for kids to get out of their hometowns and live more exciting lives.”

Walsh points to the indulgent and hedonistic music of Pulp—whose eventual and definitive Britpop anthem “Common People” captured the timeless panic and rage of trying and failing to transcend one’s circumstances—as the embodiment of the era’s original spirit. It’s not “Britain is best” but “Don’t let the bastards get you down.” Thatcher’s Children, the generation that came of age when their prime minister told them that there was no such thing as society, said piss off and reshaped society in their image, or at least in the image of their record collections.

If a generation were to reshape society, the pre-internet ’90s in the U.K. was a good time and place to do so.

“Britpop worked for a variety of reasons,” says Simon Williams, the NME journalist who in 1994 co-launched Fierce Panda Records, which, many years before coming out with Coldplay’s debut EP, released a recorded argument between Liam and Noel Gallagher that charted as a single. Williams highlights Camden Town’s early ’90s New Wave of New Wave micro-scene and its Adidas-wearing post-punkers (“Britpop without the good bits,” as John Harris put it in 2006) as a vital force that primed London to host a vibrant guitar-rock scene. Elsewhere, key hirings at the U.K.’s few major radio and TV stations (Matthew Bannister and Steve Lamacq at BBC Radio 1, Ric Blaxill at Top of the Pops) matched the curiosity and vigor of the U.K.’s historically sensational music press read by fans and musicians. This was all while the music industry was printing money from the CD boom that reintroduced the old rock and pop canon to a new generation that was rebuying the classics now influencing the new rock stars.

“With that much money coming in, people were being paid silly amounts to work in A&R and marketing,” says Walsh. “People in their 20s were given obscene expense accounts and a license to just go off and spend, spend, spend. With that much cash circulating in what was really still a pretty small scene, it leads to … widespread hedonism.”

Perhaps the most underrated influence was the 1991 collapse of Rough Trade Distribution, which distributed and supported most of the era’s big indie labels, including Creation, Factory, and One Little Indian. That forced many of those labels to make distribution deals with the major labels in a bid for survival, which became mutually beneficial. Creation was backed by Sony, Pulp got picked up by Island Records, and so on. The simplified story of Britpop: when the majors figured out how to sell indie musicians, now with the budgets to make more ambitious music for a wider audience.

It helped, too, that the U.K. was much smaller than places like the United States. If BBC Radio 1 played your song, you were famous. “You could pretty much cover the whole of Britain in terms of touring and releases in a year,” says Williams, “during which time the press and radio coverage could be pretty much nonstop.”

Blur may have stolen the spotlight from Suede and actively encouraged music written just for and about Britons—or more specifically, Londoners—but Oasis became the perfect mouthpiece for the new Britpop-industrial complex to promote the trendy New Labour sound abroad. Definitely Maybe didn’t explicitly deal with Britishness—you don’t have to be from Manchester or Leeds to relate to “Live Forever” or “Slide Away”—so Oasis was the perfect gateway drug for international ears. Not that Oasis ever asked to be Britpop’s global brand ambassador.

“I never saw Oasis as Britpop,” says Johnny Hopkins, Oasis’s original longtime press agent, who is now an academic. He considers Oasis first to be Irish Mancunians. “I never used the word ‘Britpop’ in relation to them in press releases or biographies or any conversation with journalists. But all those bands did get dragged into it, whether they liked it or not.”

Definitely Maybe indeed did not fit in with Britpop’s original mission statement of dethroning grunge. That the album did not set out to conform to some media trend is probably the exact reason it still feels compelling and authentic 30 years later. Everything from Liam’s fantastical sneering on “Supersonic” to the brutal simplicity of Noel’s guitar playing on “Live Forever” and the rhythm section totally locking in on the punchy “Columbia” and wistful “Slide Away” still screams: You, too, can play this.

“They’re universal, aren’t they?” says Hopkins about the album’s songs, many of which are some of Oasis’s most beloved. “They can appeal to someone in Manchester as much as they will to someone in Memphis, Stockholm, Osaka, Nairobi, or wherever. Those songs just work.” Funnily enough, for all of Oasis’s success, Definitely Maybe might also be the only album that everyone can agree on. “There are people who love whatever Oasis do, people who hate everything Oasis do, and people in the middle who do really like them but maybe see them as an act in two halves. Those lots, unfailingly, love Definitely Maybe,” Hopkins says.

Hopkins suggests that the real beginning of Britpop’s end, however, was also related to Oasis: when the U.K.’s infamous tabloids started paying attention.

“The tabloids took those groups as a kind of national cause,” says Hopkins of the major Britpop bands, which not only topped the charts but also provided pages of juicy news and quotes. The beloved British rock bands that predated Britpop—New Order, the Smiths, the Stone Roses—may have been gods to NME and Melody Maker readers, but those magazines were not on the same level as the gossip pages that covered Madonna, Elton John, or even the likes of Kate Moss and Naomi Campbell. A major readership outside the underground was now discovering all these Union Jack–coded bands and probably couldn’t, or wouldn’t, pick up on the nuances of young people reclaiming the U.K. flag for themselves. “You can see why the tabloids would have been interested in them, because they were successful,” continues Hopkins, “and they provided lots of great, scandalous stories, whether it’s Jarvis [Cocker, Pulp frontman] sticking his bum out at Michael Jackson or whether it was the regular everyday life of Oasis. The celebrities flock to the flame.”

There are people who love whatever Oasis do, people who hate everything Oasis do, and people in the middle who do really like them but maybe see them as an act in two halves. Those lots, unfailingly, love Definitely Maybe.Johnny Hopkins

Britpop was now blown up to tremendous proportions. It produced more incredible music. Then it got ugly. By the time of Labour’s actual election victory in 1997, Britpop’s major players had lost themselves to hubris, harder drugs, or an unwillingness to compete with the music industry’s new market-tested Britpop for preteens (the Spice Girls) or the inward-looking masterpieces by Radiohead, Spiritualized, Mogwai, and the Verve that prepped the masses for Travis, Coldplay, and the dreamy sound of 2000s guitar pop. By 1997, Britpop became the sound of too much cocaine and the fodder for glossy, three-years-too-late Vanity Fair profiles touting the era’s out-of-touch celebrities. Be Here Now, Oasis’s much-anticipated follow-up to (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, was released 10 days before Princess Diana’s death and was seen as guitar rock at its most out of touch, indulgent, and embarrassing—the bloated behemoth that pushed Britpop off the cliff.

Britpop was a fashion statement. Like with any fashion, the world eventually moved on.

The years immediately after were not kind to Britpop. Following the typical ebb and flow of culture exchange between the U.K. and the U.S., New York’s post-9/11 rock revival filled the Britpop void as the city’s regional music scene exported into the global mainstream, outlandish characters and feuds included. Following the Great Recession, the internet and then streaming services sped up the music industry’s march away from chart battles and toward algorithmic curation. Virality, without an attachment to any particular physical scene or sound, became the new gateway for upward mobility and even stardom. Britain continued to export music that found mass audiences outside the U.K.—Arctic Monkeys, One Direction, Ed Sheeran, Adele—but none of these names could easily fit under some umbrella term.

Britpop’s reputation sank to a new low around the mid-2010s. The long-running rockism vs. poptimism debate is silly and reductive, yet it’s tempting to believe that Britpop’s hubris and demise spurred poptimism’s evolution from a well-intentioned mission to take pop music seriously into an overcorrection turning pop into therapy homework, the antithesis of Britpop’s hedonism. (Just imagine Liam Gallagher trying to say “therapy” or “homework.”) In this spirit, for the next generation of music journalists, who were more diverse and had less patience to gush about Noel Gallagher’s reverence for Magical Mystery Tour, Britpop became an easy straw man to damn any music that hinted at the white male guitar privilege that in 1996 allowed Oasis to perform the largest outdoor concerts in U.K. history up to that time. Those Knebworth concerts, which once seemed like the pinnacle of popular music’s ability to bring people together, now seemed like an expensive mess. Those same journalists also had to compete for dwindling coverage space in far fewer media outlets, reversing the special fluke of Britpop, which came at a time when alt-weeklies shaped and didn’t just react to popular culture. The 2010s guitar-rock bands that were popular and critically adored—bands like the 1975, who played by Gallagher rock star rules but worked with pop producers—became the exception, not the rule.

If the working-class spirit of Britpop existed in the 2010s, it survived through smaller, more dour groups like Sleaford Mods, who made their love of hip-hop and punk more overt than any affection they may have had for ’60s mods. It’s telling, too, that the most recent notable (but more insular) U.K. indie guitar movement, the post-punk revival that included black midi, Fontaines D.C., and Dry Cleaning, chose the angrier and more obtuse the Fall over the Beatles as their spiritual avatars to navigate the uncertain future of the U.K., which did not seem as sunny as it had in the ’90s.

Albarn even got the message. Blur’s post-Britpop pivot from the Kinks to Pavement is one of the great transformations of ’90s rock (and ironically gave Blur its first big U.S. hit with “Song 2”), and Albarn’s widely successful Gorillaz project feels like a 20-plus-year multicultural apology for Britpop. The Gallagher brothers, meanwhile, chose to tour separately behind forgettable solo albums, drawing healthy crowds who patiently waited for “Don’t Look Back in Anger.”

Perhaps the most damning influence on Britpop’s reputation was the most tenuous: the 2016 U.K. referendum. To lazy critics and pundits throughout the U.K. press, Brexit’s Make Britain Great Again campaign seemed to be the manifestation of Britpop’s original mission. Hopkins warns that there is some truth in this accusation, even if it wasn’t the intention of the musicians and journalists in the ’90s.

The subtle, banal ways that nationalism can work are far more powerful because we don’t necessarily notice that it’s happening. It’s softened people up intentionally for a rightward kind of shift.Hopkins

“It’s pretty unusual to have a genre of music, scene, or whatever Britpop was defined on national terms,” says Hopkins. “There was U.K. garage in the late ’90s and early 2000s, which I guess may have been called U.K. garage partly because of the success of Britpop.”

It’s not that any of Britpop’s main players were Leavers—everyone else I interviewed did not feel that it was fair to retrofit Britpop into Brexit’s shadow—but it is fair to consider how we’re influenced by what Hopkins calls “the drip feed of little comments and symbols” that surround us all. It’s the fulfillment of British social scientist Michael Billig’s warning of banal nationalism—a term Billig coined in 1995, right in the heart of Britpop.

“[Nationalism] can come in language, it can come in subtle uses of flags, and it can come in song lyrics,” says Hopkins. “We’re always going to be wary of those people on the far right, but the subtle, banal ways that nationalism can work are far more powerful because we don’t necessarily notice that it’s happening. It’s softened people up intentionally for a rightward kind of shift.”

This is all to say that Britpop’s afterlife is a story as old as time: The underdog hero becomes the out-of-touch establishment for the next generation to rally against.

“From around the time of the financial crisis, people were still looking at the ’90s going, well, this was the reckless boom that gave us this bust that we’re all living with,” says Dorian Lynskey, a music and political journalist who has written about Britpop’s evolving legacy throughout the past decades.

Lynskey says that for a moment, the press and even some fans turned on Britpop and called it the sound of “idiot complacency,” as if it were Albarn’s fault for not regulating the banks or carbon emissions. He also suggests that Britpop is not quite the story of how coked-up nationalism took over the world. Rather, Britpop more closely mirrors the story of indie rock, in which insurgent underground energy broke into the mainstream and made popular music more interesting until the music industry caught up and hubris and confusion made the indie label’s original meaning useless. It’s not unreasonable to see Britpop as a test run for the eventual rise and fall of big indie, a warning that feels more relevant today, as we now live in a time when working-class or even middle-class musicians—anyone who attempts to make literal independent art—struggle to make a living.

Everything is cyclical, of course. “It’s very hard to get the perfect balance,” says Lynskey, who appreciates any new generation’s desire to right the wrongs of the past, which in the case of Britpop was its over-the-top laddish culture. “But I do think that you get these cycles where there’d be a great deal of guilt and anxiety. They can seem very true and profound and necessary for progress. But at a certain point, people are like, can we just have some fun?”

Indeed, it seems like music fans and musicians are finally more willing to ask whether we can have fun again. All of a sudden, the Britpop era, which Britpop pioneer Jane Savidge described earlier this year as “impossibly glamourous,” doesn’t seem so terrible.

“It was a brilliant time to be young,” says Chris Floyd, a photographer for Loaded and The Face who captured the style of Britpop in real time. “A lot of us grew up in the ’80s under the threat of atomic nuclear war. Suddenly, that all just stopped almost overnight.” Britpop, to Floyd, was also special because of its unselfconsciousness and its relative scarcity—you had to physically leave your house to go buy a record or magazine—in a time before the internet turned art into a game of badge collecting to project some social media brand.

“Britpop was a late phenomenon of the offline era,” says Paul Du Noyer, an NME and Q journalist who became the founding editor of MOJO in 1993. “By 1994 there was a growing awareness of the internet, but personal access was very limited. There was no consensus as to its likely role in music’s future, either as a conduit of commentary or as an actual listening platform.” Because of its unique relationship with the internet, which was not yet ready to be the conduit of commentary that it eventually became, Britpop was allowed to be a playpen for young people to let loose and embrace the era’s playful, life-affirming hedonism. Before the internet turned fandom into a battle of boundaries and impossible expectations, Britpop was, according to the era’s beloved journalist Sylvia Patterson, “the last carefree party.”

If that last carefree party was only recently a scapegoat for everything wrong with the ’90s, the pendulum is now maybe swinging back to the side that says Britpop captured what was so great about the ’90s. Maybe Britpop’s actual music just sounds a lot more fun than the music we’ve been given since COVID-19 lockdowns. And fun sounds nice right now, especially in the face of further economic instability and volatile politics that point to a future in which young people don’t have a shot at bettering themselves by playing by the rules. Maybe Thatcher’s Children and COVID’s Children are more alike than we might have anticipated.

To be honest, we had British music, art, film, and left-wing politics all briefly illuminating this pre-internet civilization, and it became a celebration of the homegrown underdogs taking over the asylum rather than any ghastly flag-waving patriotism gone mad.Simon Williams

“At a moment when everything feels so fractured now, there’s so much ennui everywhere,” says Kieran Press-Reynolds, the music journalist who reviewed Nia Archives’s Britpop-inspired debut LP for Pitchfork. “People want to get back in the streets and celebrate and have these kinds of anthems that everybody can get around. I feel like making a more optimistic, buoyant kind of dance sound and saying it’s a tribute to Britpop, or you’re pulling from Britpop, makes sense.”

Press-Reynolds covers many up-and-coming artists within the realms of jungle, hyperpop, and other internet-born scenes—scenes that, according to him, are less concerned with bickering over Britpop’s legacy and more inclined to expand Britpop into a larger tapestry of beloved ’90s British music. Things are different now: Radiohead was never previously considered Britpop, and now Pitchfork has named The Bends the third-best Britpop record, and Goldie, Massive Attack, Portishead, the Chemical Brothers, Tricky, the Prodigy, and more are now a part of Britpop rather than being outside or against it. He also notes that even in the age of TikTok, someone like Nia Archives, a DJ and producer who doesn’t have any viral moments to lean on, could still organically connect with an audience. She fits into the 2024 appeal of Britpop: less a coherent and strict sonic and visual identity and more an amorphous tool kit to make any kind of anthemic music.

Perhaps the media ecosystem also just stopped looking back in so much anger. That same millennial media class that so rallied against Britpop is slowly being aged out of the music industry—or simply can’t afford to work in an industry full of 26-year-olds trying to impress 16-year-olds—and is now being replaced by Zoomers who, even if they appreciate Britpop’s baggage, can’t or don’t try to hold the past to today’s standards. Britpop today now feels more exciting because of its optimism than its relationship to privilege, political correctness, or even neoliberalism.

“I can’t think of another genre that people are as tense about as Britpop,” says Lynskey, “but it feels to me that that moment has passed. If I talk to my daughter or any of her friends, they’d just be like, why would you be angry with Blur?”

Britpop is now Dua Lipa’s tributes to its influence, not because she’s writing caustic character studies of frustrated suburbanites or because she sounds like Echobelly or Elastica, but because she’s capturing the Britpop-esque feeling of her album title: Radical Optimism.

It’s hyperpop icons A. G. Cook and Charli XCX’s collaboration on a song and album called Britpop that, instead of commenting on England’s shameful past, captures a sense of fun with an edge of relatable anxiety—just like the best Oasis songs, in which an older, more world-weary Noel Gallagher wrote melancholy music for his braggadocious younger brother to turn into life-affirming anthems.

“Charli’s voice is pure Britpop in terms of personality with attitude,” Cook told DIY earlier this year. In the same interview, Cook expressed a modern interpretation of Britpop that had nothing to do with guitar dudes trying to replicate imperial England: It’s underground artists playing with universal symbols.

Britpop today is also Cook producing Charli XCX’s Brat, which, along with Chappell Roan’s slow burn and tremendous 2024, feels like a sea change for a new generation of pop stars—at least, the pop stars who are outside the Disney-industrial complex or who were not already famous before the streaming age—who are more willing to be over-the-top, stylish, bratty, and witty, just like Britpop.

It’s in K-pop—the modern interpretation of which goes back to Seo Taiji and Boys’ debut LP, released a year before McGee discovered Oasis—which learned the right lessons from Britpop and branded itself as an international soft power that, instead of acting like a nationalist declaration, simply invites listeners into South Korea’s history and culture; it’s the difference between “K-pop” and “Koreapop.”

It’s a post-internet society in which music fans grew up with unprecedented access to more varieties of genres and don’t feel a disconnect between loving Oasis and Goldie, a disconnect that was never shared by Britpop’s originators but was encouraged by the press.

It’s in modern music technology algorithms that intentionally promote new content outside its original context, resulting in maybe the cruelest Britpop irony: Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and Oasis’s “Wonderwall” now live at the same retirement community where all old music waits around to hopefully go viral one day.

It’s Britpop’s recovery from its perceived relationship with nationalism.

“My own take would be that musicians, fans, and commentators of that time felt a cultural pride in the global prominence of British pop since the Beatles,” says Du Noyer. “This small and rather diffident nation that had somehow come up with the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and all the rest. … The matter of Brexit is difficult to retrofit onto 1994. The word itself did not exist, obviously, and opposition to the EU was in those days led by the political left more than by the right.”

Williams goes a step further. “To be honest, we had British music, art, film, and left-wing politics all briefly illuminating this pre-internet civilization, and it became a celebration of the homegrown underdogs taking over the asylum rather than any ghastly flag-waving patriotism gone mad. In many ways, I feel like the end of the last century was the last time humans were decent towards each other.”

A new generation now misremembers Britpop more fondly, which feels like a victory for music fans hoping that the success of Brat and the relatively lukewarm receptions for new albums by Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, and Billie Eilish mark a transition in popular music, which for years has felt trapped in a COVID slumber. Like Thatcher’s Children rallying against their coming of age, COVID’s Children are making that same rallying cry and looking for new anthems.

Or maybe it’s just that enough time has passed and the rough edges that gave Britpop its initial power have softened. The emotional depth and nuance of Britpop’s actual music will always be underrated, but it’s nice to know that the best of the bunch will stay with us while all the hype and misrememberings fade away.

The next Britpop will likely not have guitars—although you never know—but will still involve a bunch of driven young people looking at some symbol of modernity and wishing to flush it down the toilet. As long as lazy culture writers continue to try to manifest indie sleaze into reality, Britpop—the original indie sleaze—will continue to matter. As long as weirdos from actual working-class backgrounds can still achieve no. 1 hits, Britpop will feel like the dam breaker that forever made the potential of pop music more interesting. As long as people still care about albums and music’s ever-morphing history, Britpop will matter.

Anything is still possible. Anyone, and anything, common can live forever. It’s nothing special.

Brady Gerber is a writer, journalist, and music critic based in Los Angeles. He contributes to New York magazine and Pitchfork and has appeared in The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Stereogum, McSweeney’s, and more. Brady is also the founder of OPE!, a music blog and newsletter.