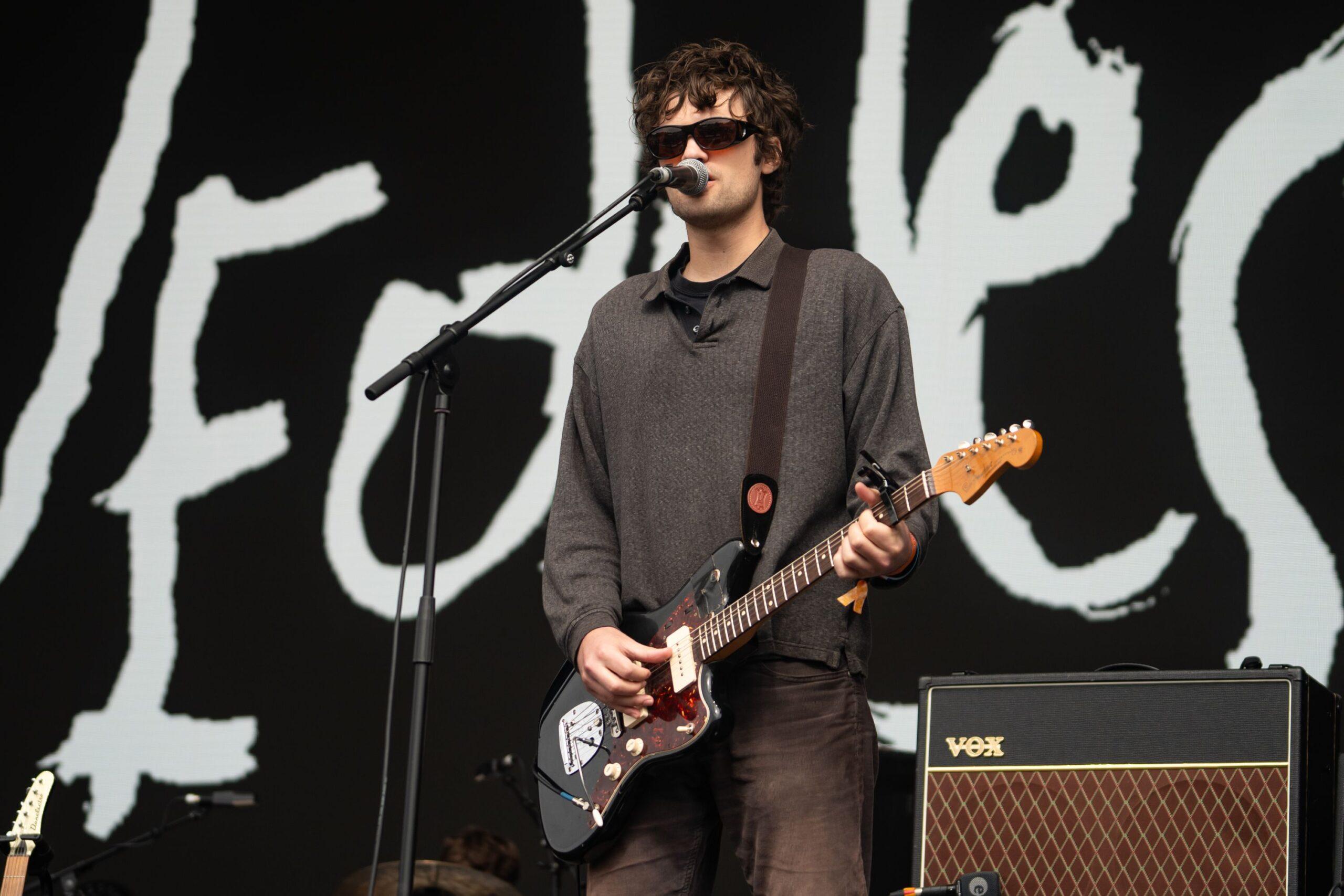

MJ Lenderman, Indie Rock’s No. 1 Prospect, Goes Pro

With his new album, ‘Manning Fireworks,’ Asheville’s own guitar hero meets the moment and becomes one of rock’s most promising songwritersFive years ago, War on Drugs bassist Dave Hartley moved to Asheville, North Carolina, with his wife and young daughter. He’d lived in Philadelphia for 16 years, but his band had spent time recording and touring in the small Blue Ridge Mountains city. “We always had this impression that there was a music scene there, but it was mostly bluegrass and jam bands, and there wasn’t much homegrown,” he says. “People would move there from other places because it was a vibe-y town.”

He bought a house and eventually hired some people to help with the landscaping. They were the college-aged couple MJ Lenderman and Karly Hartzman, and they were lousy landscapers. “They were just kids working odd, shit jobs,” Hartley says. “It was all so reminiscent of my teeth cutting in Philly. I could see it from space—oh, you’re in a band and someone told you it was 20 bucks an hour to pile up debris in someone’s yard.” Hartzman started babysitting Hartley’s daughter, and he found out about her group Wednesday, which Lenderman also plays guitar in. “I listened to it and it was like, oh man, you’re not going to be babysitting for long,” Hartley says.

Soon he also heard Lenderman’s album Ghost of Your Guitar Solo, which, unlike the confessional and at times ferocious approach of Wednesday, was more laid-back and threaded with sly comedy. Hartley was similarly impressed. “It was clear that he taps into this set of influences that is really unique, to my ear, and it’s done not so much with confidence, but this low-key, unassuming ease,” he explains. “I just said to myself, ‘Oh, OK, noted, this is real.’ It was real shit from the jump.”

Lenderman has put out a new album every year since 2021 (including one live record), and this week he keeps the streak going with Manning Fireworks, his first collection of new material for ANTI- Records. In an astonishingly short amount of time, Lenderman has gone from barely known to one of rock’s most promising songwriters. He first started to get attention with compositions laden with knowing humor and off-kilter sports references—Dan Marino seeing Tom Brady’s face replace his on a Wheaties box, the brutal toll that the WWE’s Attitude Era had on wrestlers’ bodies, the impression Jack Nicholson’s ass cheeks left behind on the Lakers courtside seats—but he’s quickly developed into an expert chronicler of misguided masculinity. With an economy of words, he captures a society where men are desperate to be seen as the alpha, but none of them have any idea how to lead the pack. Just when he seemed destined to be defined as peak indie bro, he’s revealed himself to be a masterful satirizer of bro culture.

His music is a blend of ’90s indie scrappiness, rangy ’70s rock, and classic country that’s woozy with pedal steel guitar. In his lyrics he presents a cockeyed vision of Americana where a strained couple sits under a half-mast McDonald’s flag and an intoxicated Lightning McQueen leaves behind a mangled roadkill victim (KACHOW!). It’s all so horrible and absurd that you might as well get a laugh out of it.

He openly cops to the artists who’ve influenced him: Neil Young, David Berman, Will Oldham, Bill Callahan … “I think just with the music we make, they’re pretty obvious,” Lenderman says during a July video call. “They come across in the recordings. And if it’s my band, I kind of have final say of what the reference points are going to be.”

Lenderman, 25, lived most of his life in Asheville. “The more I go other places, the more I realize how special it is,” he says of his hometown. “Just the air is really nice. The mountains. It’s cool people, for the most part.” He doesn’t really know what brought his parents to Asheville. They both grew up in Virginia, went to UVA, and got married in 1991. Two years later, they headed farther south. There they raised four kids, evenly spaced two years apart from each other—three daughters and Jake, as everyone who knows him calls him (MJ is short for his given name, “Mark Jacob”).

For decades, Asheville has depended on vacationers to sustain its economy, so much so that the local minor league baseball team is named the Tourists. People come to the area to hike and camp, especially in the fall, when the leaves of the dogwood and hickory trees turn vivid hues of red and yellow. Lenderman has become acutely aware of the changes happening to the city over the years. More hotels for the people visiting. More housing subdivisions and sprawl for the ones who decide to make it permanent. “It’s had a reputation of being a weirdo place, like a hippie kind of town, and now maybe they’re just rich hippies,” he says. “The microbrewery scene really blew up in the last 15 years as well.”

Lenderman says his parents weren’t hippies. Maybe you could call them hippie sympathizers. His dad is a longtime Deadhead, with bumper stickers on the car and everything. Nevertheless, they sent him to Catholic school through sixth grade, until he convinced them to let him go to a public middle school. Religion hasn’t been a part of his life since he had his confirmation. Yet there were elements of the institution that once appealed to him. “I genuinely did think I wanted to be a priest when I was a kid, because it was just out of laziness,” Lenderman says. “The thought of figuring out something else to do stressed me out. But I guess as soon as I hit puberty, I couldn’t do that.”

Lenderman’s music is sprinkled with classic rock allusions and inside jokes. Two songs on Manning Fireworks, “You Don’t Know the Shape I’m In” and “Bark at the Moon,” reflect track names from the Band and Ozzy Osbourne, respectively. Lenderman was alive for only 11 months of the ’90s, but that period, which he calls “the last era before I can remember anything,” remains a particular influence on him. Like many people his age, he’s not only drawn to it aesthetics—how the music sounded, how people dressed, how the movies looked—but its flawed icons also haunt his songs, whether he’s referencing golfer John Daly belting out “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” or poking holes in the myth of Michael Jordan’s performance in Game 5 of 1997’s NBA Finals with the song “Hangover Game,” which ends with the words “I love drinking too.”

Though Lenderman’s influences are rooted in the 20th century, several of his formative musical experiences could have happened only in this millennium. When he was 7, he and a friend got really into the Guitar Hero video game series. It opened Lenderman up to songs like Slayer’s “Raining Blood” and the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s “Spanish Castle Magic.” Soon they were taking actual guitar lessons together, quickly dissuading their instructor from teaching them how to read music and instead just asking how to play certain riffs. “He was more of a jazz guitarist, and I feel like my brain kind of checked out once we learned how to play the rock pentatonic scale,” Lenderman says. “The jazz theory stuff, just modes and all that, went way over my head at the time. So maybe I’ll try to understand those soon.”

As for why he’d want to do so at this stage, he jokes, “So I can sit in with the Dead.”

Lenderman also went to one of the many rock band summer camps that sprouted up after the success of the Jack Black movie School of Rock. It was there that he met Ethan Baechtold, who is now the bassist in Wednesday and keyboardist in Lenderman’s touring outfit.

As he grew older, he would play and listen to music constantly. “That was really the only thing that I ever wanted to do,” he says. In high school, his creative writing teacher was also in charge of the slam poetry group. While Lenderman never took part in that extracurricular, they would let him play a couple of songs during the breaks in their performances.

During that time Lenderman met an upperclassman named Colin Miller through one of his sisters. “Jake was in this band of 15-year-olds, and they were all incredible musicians, and still are,” Miller says. Upon graduating, Miller worked for two months at a recording studio that specialized in Christian music (which he didn’t know until his internship started), and then he began the music technology program at University of North Carolina, Asheville. To get his chops up, he recorded his friends, with Lenderman becoming a main pillar of the people he worked with. These days, Miller is the drummer in Lenderman’s band.

When he was younger, Miller was uninterested in Asheville’s existing local music scene. He figured if he was going to pursue music as a career, he’d probably have to leave town. But along with Lenderman and the others around them, they started building their own community, often playing shows at the now-closed club the Mothlight while simultaneously gazing outward. “It was like, oh, this is how we do it, this is our version,” Miller says. “We’re going to make people look at us because we’re doing the things that we love. Sonic Youth was local music for New York, so local music isn’t just a bad term.”

As a teenager in Asheville, Miller lived on a former farm with three buildings: the big house his parents rented, a nearby smaller house, and a house where the landlords, Gary and Margaret King, lived. When Miller’s parents left in 2015, he remained. Lenderman became his housemate in 2018. Other friends and band members cycled through. Eventually, Lenderman moved into the small house with Hartzman. “Being that close, we never locked our doors and would walk into each other’s houses and hang out every day,” Miller says.

That was the living arrangement during the worst of COVID, and during that time, Lenderman finished Ghost of Your Guitar Solo and then Boat Songs, which found its way onto multiple best album of the year lists in 2022, despite its modest ambitions. Critics were taken with its lived-in, idiosyncratic charm. Pitchfork described it as “like a particularly crunchy bite into a grilled cheese sandwich,” while Stereogum said it “belongs on the river, reeling in a crushed Natty Lite.” At The Ringer, Rob Harvilla wrote, “Boat Songs is occasionally so shaggy and lo-fi it sounds like ol’ MJ fell out of said boat, but when the scruffy electric-guitar riffs mesh with the pedal steel just right, boom, transcendence.”

During the pandemic, Rusty Sutton, a veteran music manager who works with acts including Generationals and Wye Oak, moved back to his native Asheville from Durham, North Carolina. Not long after that, he began managing Wednesday, and then Lenderman as well. The tone of Lenderman’s songs felt both familiar and unheard of to him. “There are turns of phrases in his songwriting that remind me of my dad’s friends when I was growing up,” Sutton says. “There is an entire world of truly brilliant, really hilarious people out there that are just middle-class lifers. Jake grew up around that, and he writes from that perspective, and it’s really earnest and brilliant and hilarious and fun. And I think that’s why people connect with it and that’s why I connect with it. I just feel at home with this guy.”

In early 2022, a couple of months before the release of Boat Songs on the small Northeastern indie Dear Life Records, Sutton sent the album to Allison Crutchfield. Though known for her band Swearin’ and solo work, a few years earlier she’d become an A&R at the L.A.-based label ANTI-. Just seconds into Boat Songs’ opener, “Hangover Game,” she was convinced and spent most of the year working on signing Lenderman. The contract finally got finished right before winter vacation.

Crutchfield grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, where she played in the bands P.S. Eliot and the Ackleys with her twin sister, Katie Crutchfield, who now records as Waxahatchee. But Allison didn’t really get attention as an artist until she moved to Philadelphia. “I’m about 10 years older than Jake, and I think that I had a really different experience with my Southernness,” she says. “Immediately as I came of age, I wanted to move away, I wanted to move to New York, I wanted to lose the accent, I wanted to lose all traces of that—there was something about it that felt really uncool to me. As I get older, I find myself really trying to reconnect with that. For all these reasons, Jake and Wednesday, that scene, their whole embrace of where they come from, there’s something about that that really struck something in me personally.”

In 2023, Lenderman joined Wednesday as they released and toured in support of the acclaimed album Rat Saw God. He also played guitar throughout Waxahatchee’s Tigers Blood, which was released this past March, and acted as the harmonizing Emmylou Harris to Katie Crutchfield’s Gram Parsons on several tracks, including the standout single “Right Back to It.” Amid these endeavors and his own tours, he managed to record Manning Fireworks in spurts over the course of a year.

Manning Fireworks is filled with tales of men who use bluster to cover up their flaws and inherent ridiculousness. On “Wristwatch,” Lenderman inhabits a blowhard who brags about having a beach home in Buffalo and thinks his futuristic tech is a passable substitute for a decent personality, while the weary “Rip Torn” scrutinizes an unspecified someone whose overindulgences leave him passed out in his Lucky Charms and whom Lenderman dismisses with the devastatingly clinical put-down “You need to learn how to behave in groups.” And though Lenderman’s portraits are unsparing, he isn’t cruel, and some sliver of humanity in his subjects usually pokes through. “Jake is a really funny person, but he’s never the loudest person in the room,” Crutchfield says. “His songwriting is a way for that humor and that real sense of observation to come out.” As he sings on “Joker Lips,” a song about spiraling out when you don’t feel like your life has a purpose, “Please don’t laugh, only half of what I said was a joke.”

Lenderman has toned down the sports references in his songs, but on Manning Fireworks he performs like an athlete who, as the cliché goes, realizes what’s on the line and ups his game. “It really showcases him stepping into his moment,” Crutchfield says. “There’s a level of confidence on this record that is pretty palpable, and not in a way that is off-putting and not in a way that feels egotistical.”

He played most of the instruments on Manning Fireworks himself and produced it at Asheville’s Drop of Sun Studios alongside Alex Farrar, its co-owner and his frequent collaborator. Lenderman recorded Boat Songs at Drop of Sun’s previous incarnation as a home studio but embraced the newer, more professional setup. “They make it really comfortable there,” he says. “The two guys who started the studio, all their families are pretty involved. Alex just had a baby, and so the baby was popping by sometimes.”

In these updated environs, he was able to both embrace what’s worked for him as an artist and shed some of the trappings of his previous albums. “I approached it the same as I normally would, trying to avoid having demos so you can really build the song in the studio,” Lenderman says. “I avoided the lo-finess of the older stuff. It felt like the main goal was just capture what the instruments sound like naturally.”

It’s a progression that is exciting and expected for those who’ve known for years what Lenderman is capable of. “He’s able to take things that aren’t necessarily new and make them feel new, because he’s appreciated them so honestly and so deeply for so long,” Miller says. “Music is his favorite thing to do. There are lots of things in life that are easy to push you away from music, and Jake’s had the sense and luck to be able to be fully in it. It’s an inspirational thing to be around.”

While Manning Fireworks may be the crystallization of what Lenderman has been working toward, it also marks the end of an era. Lenderman, Hartzman, and Miller had to leave their affordable Asheville rentals this past May because of the property’s imminent sale after the deaths of its owners. Even though they had broken up as a couple, Lenderman and Hartzman moved together to Greensboro, a town a few hours away. Lenderman is still a member of Wednesday but plans to relocate even farther east to the Raleigh-Durham area soon.

Though it’s been a productive past few years, Lenderman hasn’t started working on new songs yet. For now, he’s just ready for Manning Fireworks to be out in the world. “I’ve gone through all the stages of, I don’t want to say grief, but it’s kind of like a similar process while it’s happening,” Lenderman says. “It’s like, what am I doing? And then it’s like, oh, this is pretty good, this is so fun. Then it’s like, oh, this is weird, I don’t know what this is anymore. Now that it’s finally coming out, I feel like that’s over and it’s not really any of my business anymore.”

Eric Ducker is a writer and editor in Los Angeles.