Editor’s note, September 17, 2024: This piece was originally published on August 20, 2019, when the seventh episode of Break Stuff: The Story of Woodstock ’99 was released. To mark the recent 25th anniversary of the festival, The Ringer is resurfacing Break Stuff on its own dedicated Spotify feed.

In 1999, a music festival in upstate New York became a social experiment. There were riots, looting, and numerous assaults, all set to a soundtrack of the era’s most aggressive rock bands. Incredibly, this was the third iteration of Woodstock, a festival originally known for peace, love, and hippie idealism. But Woodstock ’99 revealed some hard truths behind the myths of the 1960s and the danger that nostalgia can engender.

Break Stuff, an eight-part documentary podcast series now available on Spotify, investigates what went wrong at Woodstock ’99 and the legacy of the event as host Steven Hyden interviews promoters, attendees, journalists, and musicians. We’ve already explored whether Limp Bizkit was to blame for the chaos, how the story of the original Woodstock is mostly a myth, how the host town prepared for the festival, how the first night of Woodstock ’99 set the stage for what was to come, what the human toll of the festival was, and the sexual violence that occurred. In this episode, we’ll look at the Sunday night riots that most people remember the festival for.

Below is an excerpt from the seventh episode of Break Stuff. Find the series here, and check back each Tuesday and Thursday through September 19 for new episodes.

By early Sunday morning, on Woodstock ’99’s final day, many attendees were still trying to sleep off the previous night’s partying. But the media people covering the festival were up with the sun. In the harsh light of day, Griffiss Air Force Base looked like a wasteland.

“We got there before anybody had started playing, before anybody had left their tents,” says Dave Holmes, an on-air host for MTV in 1999. “I got a photograph from the stage of the entire lawn, the main viewing area, and it was just a sea of trash and one single person face down asleep. Not on a sleeping bag, just on the grass. It was just him and a thousand hot dog wrappers and red Solo cups and napkins for as far as the eye can see. And that is my enduring image of Woodstock ’99.”

Rob Sheffield, who covered the festival for Rolling Stone, was also up early that morning, surveying the damage.

“Everybody was really pretty used up and burned out by Sunday morning,” he says. “I hadn’t done a drug all weekend and I felt like the wrath of God so I can just imagine how people who were literally hungover were feeling.

“I slept on a pile of pizza boxes. Pizza boxes were a very good surface to sleep on because pizza boxes are white. And, uh, because they’re white, you could tell if they’d been urinated on or not. Which makes them very very useful if you’re looking for something to sleep on. Because every flat surface there had been so thoroughly urinated on.”

The music on Saturday culminated with some of the loudest and most aggressive bands of the entire festival: Metallica, Rage Against the Machine, and Limp Bizkit. Sunday, however, started on a much different foot musically. Wearing sunglasses and his signature black hat, Willie Nelson attempted to bring a little mellowness back to the festival.

“His set begins with ‘Whiskey River,’” Sheffield says. “And that was one of the great musical moments of the weekend, ’cause I just remember everybody really kind of breathing a sigh of relief. Willie is going to take care of us. Willie is the smart sane adult in the room at this point—not the promoters, definitely not the security people.”

But the laid-back feeling Nelson brought to Woodstock ’99 was short-lived. Not long after Willie Nelson left the stage in clouds of marijuana smoke, another smart, sane adult—Elvis Costello—came out.

Now, I love Elvis Costello. I am a rock critic, after all. I think he’s one of the great singer-songwriters of the ’70s and ’80s. But Woodstock ’99 wasn’t exactly his crowd. In the video, you can see people throwing water bottles at Elvis before he’s even reached the chorus of his first song.

“Elvis Costello, he really tried, but he was with an acoustic guitar and was playing for the most part for a non–Elvis Costello–cultist kind of crowd,” Sheffield says. “He began with a deep cut from Spike, ‘Pads, Paws, and Claws,’ and it was just a preposterously bad performance that was self-indulgent in a rock star kind of way. It was just really kind of abrasive and aggravating for people. ... The collective angst level of the crowd got a little uglier.”

I remember everybody breathing a sigh of relief. Willie is going to take care of us. Willie is the smart sane adult in the room at this point—not the promoters, definitely not the security people.Rob Sheffield

The bad feeling that Rob picked up on during Elvis Costello’s set was also felt by Jake Hafner, a 23-year-old Syracuse man hired to work for the festival’s Peace Patrol. Jake and his fellow guards were already struggling to contend with a depleted security force. By Sunday, many of Jake’s coworkers had already been fired; others simply quit once they were inside the base in order to join the party. But when Jake showed up for his shift on Sunday afternoon, the tension in the air was even sharper and more intense.

“It would get a little closer to the edge every night,” he says. “By Sunday when we showed up for work we all knew collectively that something was going to happen that night. It was just in the air. You could just feel it.”

That feeling in the air might have just been sheer exhaustion. Many people were operating on very little sleep by then. During the previous night, security guards had given up on policing the campgrounds where many attendees stayed.

“They had stopped sending ambulances or cops into that area because as soon as they would enter in there they would just get pelted with rocks and mud and everything. It was kind of like a no man’s zone,” Hafner says. “So they stopped sending people in there altogether. And I believe that was where a lot of the really bad stuff happened.”

One member of Woodstock’s medical team who did venture into the campgrounds on Sunday morning was Dave Konig, an EMT.

“When you went through the campground, a little bit it reminded you of a refugee camp from the movies,” Konig says. “That there had been some sort of big battle and there’s just trash all over, things burnt all over from the night before, from whatever campfires had gone on. So you just saw that breakdown of both the structure and civility amongst people. Yeah, it was definitely palpable Sunday morning. But yet people still went to the stages.”

While most attendees were still able to maintain some semblance of sanity, Dave does remember encountering a man in the campgrounds who had clearly gone off the deep end. I say “clearly” because the man was completely naked and seemed like he was hopped up on some combination of drugs. He was so out of it that he was destroying every tent in sight.

Finally, one of Dave’s coworkers decided to intervene.

“I remember this guy stepped up to, to, this naked man,” Konig says. “He gave this guy a right hook like Muhammad Ali. He just hooked him so hard. The guy’s head snapped to the right. And then ... he was like the Terminator—it just slowly turned back and then he looked at the guy who had just hit him and he was just like, ‘Rawr!’ And … everybody just tackled him at that point. We tackled him. We got him restrained, sedated, and brought him in.”

The rising tension was getting to MTV’s Holmes. Festival attendees had been abusive to the music channel’s hosts and camera crews since Friday. Someone even threw a bottle of urine at TRL host Carson Daly.

By Sunday, the MTV contingent was thoroughly rattled.

“Even before the rioting—that’s a fun way to start a sentence, even before the rioting—it seemed like this was not going to be remembered as a successful festival,” says Holmes. “When we got back to the Air Force base the next day, all anybody was talking about was how scared they were the night before. A lot of the cameramen and the production people were up in this tower that, like, could have been brought down like a scene from Game of Thrones in the middle of the show. People were understandably a little nervous that Sunday.”

That tension boiled over during a press conference in the afternoon. Someone from MTV confronted Woodstock ’99 promoter John Scher over the festival’s failure to control the most violent attendees:

“MTV News was forced to get off of home base, we felt it was too dangerous,” the reporter said. There were people throwing glass bottles everywhere. MTV tower people had to be evacuated.

“Calm down,” Scher responded.

“In all of the concerts I’ve seen, I have never seen anything quite so out of hand as this. It was violent, it was dangerous, it was hostile,” the reporter continued. “My question for you is why did no one from either security or the organization walk out to Fred Durst and say, ‘Man, can you ask these kids to chill?’ I talked to kids later who were petrified out there.”

The confrontation was a rare sour note for Scher at that point in the festival. As far as he and other organizers were concerned, Woodstock ’99 was going along swimmingly. All of the tensions that seemed obvious to those on the ground weren’t apparent to the people running the festival.

“Right after that, I took a walk from the press tent to the stage and this woman journalist, I can’t remember her name, but she walked and said, ‘Can we talk?’” Scher says now. “And at one point we stopped and she said, ‘This is unbelievable. This is the greatest thing. If you put this many people at any other kind of event, it never would have gone that well.’ She said it was just amazing. And then it all blew up over the next couple of hours.”

It turns out that the expectations were way out of whack. What was actually in the works was a candlelight vigil organized by an anti-gun group. By Sunday afternoon, they were handing out candles to attendees.

“And the peace candles became the kindling for the fires that became part of the riot,” says Brian Hiatt, a journalist who covered Woodstock ’99 and later did a yearlong investigation into the festival.

The cameramen and the production people were up in this tower that could have been brought down like a scene from Game of Thrones in the middle of the show. People were understandably a little nervous.Dave Holmes

In his reporting, Hiatt discovered that attendees had been setting fires all over the grounds throughout the weekend. And yet nobody ever seemed to get in trouble for it.

“As they put out those fires, the attendees were already threatening to make more fire,” Hiatt says. “They said, ‘We’ll burn anything.’ The threats were, ‘You can’t stop us. If you stop us, it’ll start somewhere else.’”

As late afternoon turned into early evening, the crowd grew increasingly disgruntled and unruly. And then, one of the most popular rock bands of the era showed up on stage: Creed. At Woodstock ’99, they were received like rock royalty.

However, Creed guitarist Mark Tremonti remembers Woodstock ’99 as kind of a terrifying experience.

“Back then in ’99, we’d only been kind of a professional touring band for about two years, so I didn’t have the stage confidence that I have now,” he says. “So it was I just remember it being such a large and intimidating type of setting.”

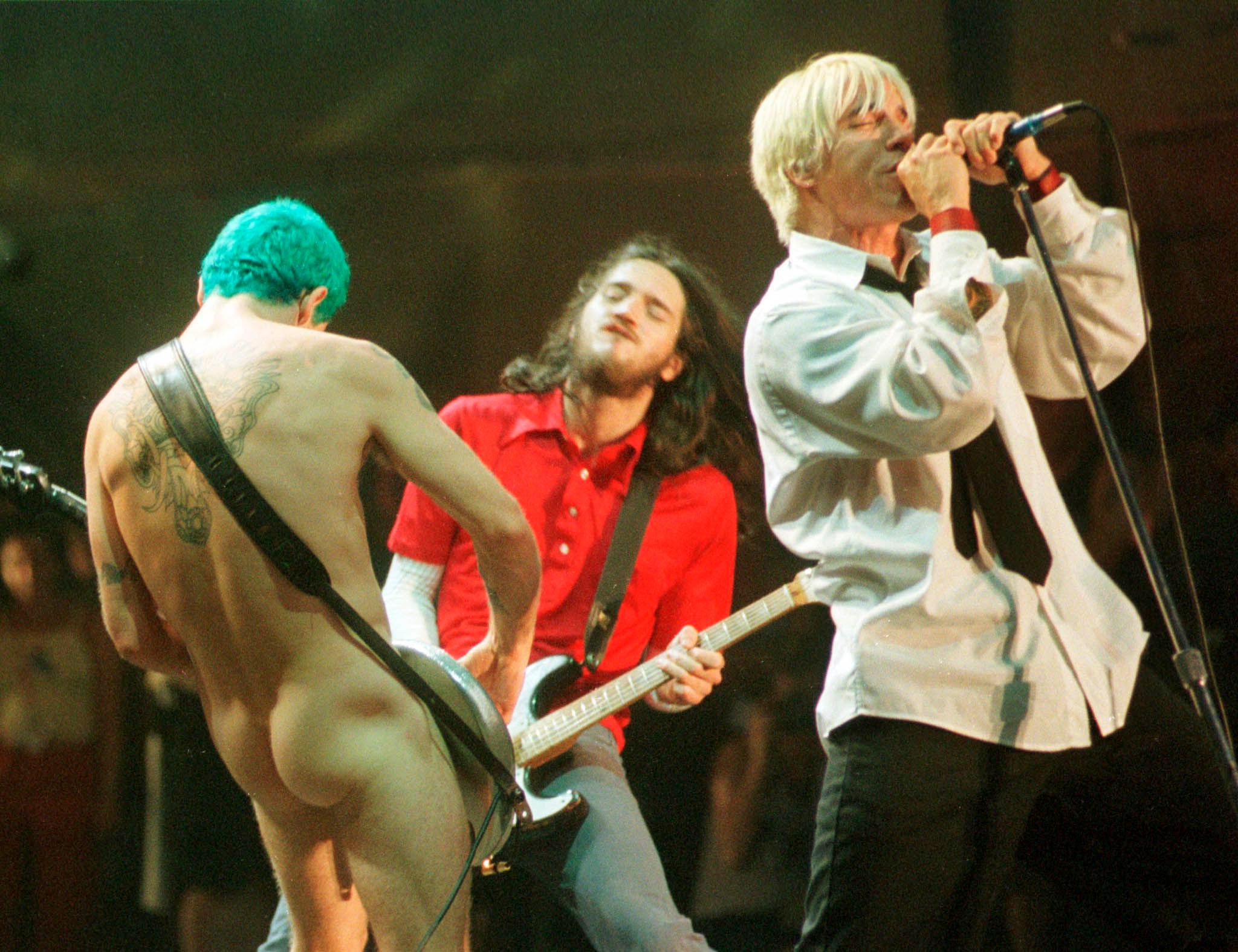

Soon after Creed left the stage, Woodstock ’99 would descend into riots. But Tremonti can’t recall feeling any premonitions. After Creed it was time for that night’s big headliner—the Red Hot Chili Peppers. The band was riding high again that summer after years of inaction. The album Californication, which became the band’s best-selling record, came out the previous month.

Their performance was supposed to mark the festival’s triumphant climax. And the band was primed for the decadent atmosphere. No one more than Flea, who came out wearing his bass guitar … and no clothes.

“It seemed like they were playing very well,” Sheffield says. “It was really a beautiful Chili Peppers set. They were coming off Californication. They had the best songs of their career, and they were playing at the peak of their career. So it’s weirdly incongruous. That’s when the violence and the crowd got really, really ugly.”

After playing for about an hour, the Chili Peppers left the stage. Before they could come back for their planned encore, the chasm between the stage and the audience suddenly collapsed. John Scher himself came out to warn the audience.

“As you can see, if you look behind you, we have a bit of a problem,” he said.

The problem was a bonfire raging on the horizon. Actually, the word “bonfire” doesn’t do justice to this wild inferno. In a video posted on YouTube, it looks like a small cabin that’s been totally engulfed in flames. But in the chaotic context of Woodstock ’99, it didn’t seem out of place at first.

Even with part of the festival now on fire, the show didn’t immediately end. When the Chili Peppers came back out, singer Anthony Kiedis commented sardonically on the situation.

“Holy shit, it’s Apocalypse Now out there. Make way for the fire trucks!” he said

And then they proceeded to play a cover of “Fire” by Jimi Hendrix. I think that this was supposed to be part of the festival’s grand finale—a callback to one of the biggest stars of the original festival, coupled with the candlelight vigil that was now a full-on blaze.