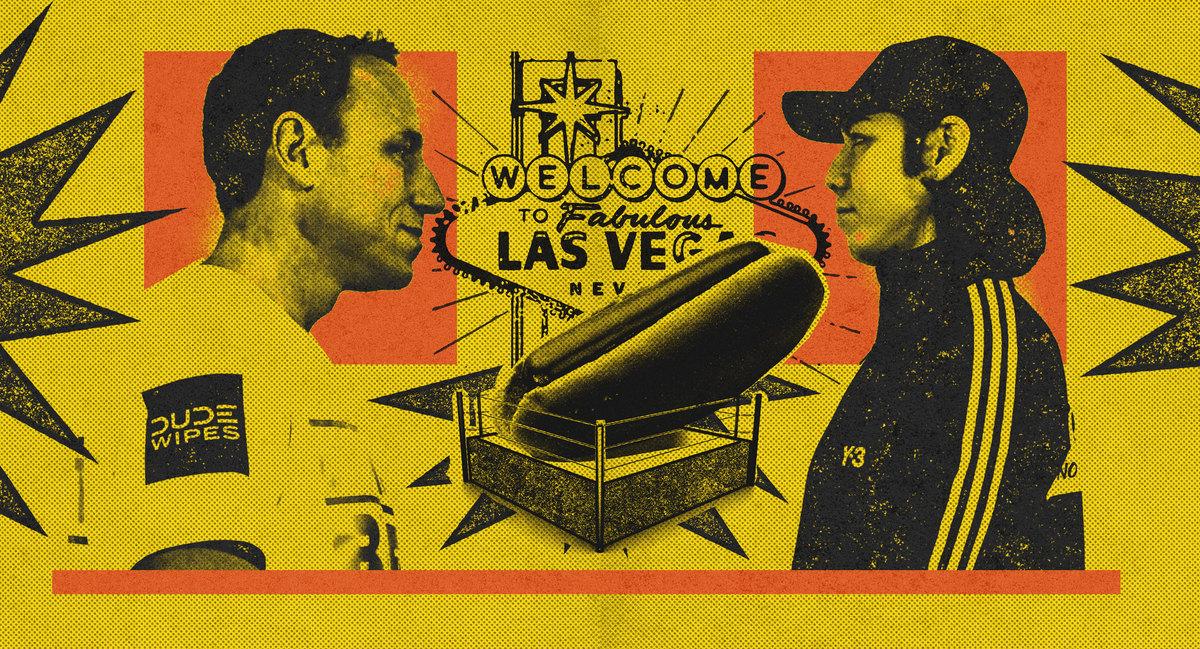

What’s Beef: The Past, Present, and Future of Joey Chestnut and Kobayashi

More than 15 years after their rivalry raised the profile of competitive eating, Chestnut and Kobi met once again in a hot-dog-eating free-for-all. But this time it was for Netflix—and maybe themselves.Today is not the Fourth of July. That is both a fact and a feeling during Netflix’s live broadcast of Chestnut Vs. Kobayashi: Unfinished Beef. (Perfect title, wouldn’t change a pun, or should I say bun—I’m so sorry.) The date, or lack thereof, shouldn’t be terribly noteworthy given that 364 days of all non–leap years are also not the Fourth of July … but when you’re watching Joey Chestnut and Takeru Kobayashi slurp down dozens of hot dogs into body cavities unknown, facing off for the first time in 15 years, the date and its proximity to patriotism matter. Patriotism always matters when it comes to hot dogs and their competitive consumption. At least, that’s the story we’re told.

For decades, the best competitive eaters have convened annually to eat one brand of hot dog, on one American holiday, broadcast by one TV network, in front of one iconic establishment.

But, again, today is not the Fourth of July, and I am not standing under those neon lights. Instead, Netflix has chosen perhaps the second most American holiday, Labor Day, in an effort to prove that its hot-dog-eating contest will be just as patriotic as any Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Eating Contest has ever been. And sure, working on a holiday that celebrates working, to cover a sport that celebrates hot dogs, does feel, in a phrase: extremely American. But I don’t blame Netflix, or The Ringer, or the organization of the American labor movement for this. I can only blame my insatiable hunger for drama. Beef, as it were.

And there is simply so much beef stuffed inside the meat grinder of competitive eating. The hawking of heroes and turning of heels; something called “jawthritis” and accusations of water-based cheating; American dreams of becoming a fiction writer dashed, and legacies built up from the ashes; contract disputes; more contract disputes; ever more contract disputes; and also, quite a bit of xenophobia. “When you’re the only player in town, it’s sometimes hard to see the humanity of others,” Nicole Lucas Haimes, director of The Good, the Bad, the Hungry and executive producer of Unfinished Beef, says of these contentious pivot points in competitive eating. “We see that in all kinds of endeavors beyond hot dogs, where the people who are involved in single-minded pursuits lose sight of the big picture.”

Or maybe the big picture of competitive eating just looks different for each of its biggest players. Maybe there’s a new big picture in town, and it’s got streaming capabilities, a big ol’ cash prize, and an even bigger belt. Indeed, you cannot talk about this Netflix Labor Day face-off 15 years in the making without first understanding the Nathan’s Famous Fourth of July contest: the men who’ve made it an institution and left it behind in equal measure; its aforementioned belt and that belt’s unexpectedly nationalistic origins; its series of unholy alliances, born of marketing tactics and sustained by sheer athleticism and an insatiable hunger to win, all meshing together to create a shockingly riveting sport. Yes, I said sport.

All of this is the reason I’m deboarding a plane into the triple-digit Las Vegas heat to watch the definitive controversial hot-dog-eating contest, in a lifetime that has apparently been full of them, to finally answer that age-old, deeply American question: Where’s the beef?

Labor Day 2024

60 Minutes to Hot Dogs

Joey Chestnut signed a deal with Impossible Foods, and now I’m wearing a pair of hot dog glasses and a hot dog bucket hat—both technically vegan—and sitting on the edge of my seat, about to watch two men in their 40s gain 20 pounds in 10 minutes.

The Coney Island boardwalk and ESPN have been swapped out for the HyperX Arena Las Vegas and Netflix. Inside there are several hundred screaming fans, and one of the more eclectic press boxes I’ve ever been a part of. Everyone from Food & Wine to BroBible and Barstool Sports to The New York Times is waiting to see what the first face-off between Joey Chestnut and Takeru Kobayashi in 15 years will mean for the sport of competitive eating, Netflix’s foray into live events, and the ever-developing culture of being a hater.

When I speak with Chestnut ahead of the event, he is, indeed, in full-on hater mode, with his signature grin quirked up to an 11 on the right side of his face (soon to be full of hot dog). One of the many thrilling elements about the dramatic announcement that Chestnut would be moving on to Netflix after being unceremoniously banned from the Nathan’s contest this year—a competition he’s won 16 times—was that his last worthy hot dog rival would also be coming out of retirement to battle him. Over a decade after parting ways with Major League Eating himself, Kobayashi announced in the 2024 Netflix documentary Hack Your Health: The Secrets of Your Gut that he was retiring from competitive eating altogether—a career that’s earned him in the high six figures annually. In the documentary, he cited his inability to feel hunger or fullness any longer, and wanting to work on his gut health.

“What, you believed that? You can’t believe that,” Chestnut laughs at my naivete. Clearly I’ve never experienced the Machiavellian highs and lows of a hot dog rivalry. “Remember when he had a jaw injury? You remember that documentary?”

I do.

“Why would he do the jaw injury? To try to get me to get lazy. And somebody had told me he still wanted to do another contest. He was trying to get me to be lazy, I think.”

The ramblings of a paranoid athlete obsessed with the competitor trying to unseat him? Or a man with a Michael Jordan–level preoccupation with competition who’s used his inherent nature to propel the niche sport of competitive eating into the national zeitgeist? A man who, for the past decade, has mostly been stuck with only himself as a worthy competitor?

While Chestnut is giving me every bit of behind-the-scenes sports drama I’ve become accustomed to receiving from Netflix’s narrative take on sports, I realize I do not feel entirely physically or emotionally prepared to watch these glizzies get guzzled. The tacit grossness in learning how the competitive-eating sausage gets made has been one thing. But facing head-on the reality of two men stuffing six-plus hot dogs per minute down their gullets for 10 consecutive minutes? It’s a lot. And I’m absolutely forced to look that reality in the overstuffed face when, during the pregame entertainment outside of HyperX Arena, Matt Stonie eats 53 chicken wings in three minutes, smoking the three Olympians he’s battling (welcome back to mess, Ryan Lochte, we missed you!). It’s long been suggested that competitive eating could technically qualify as an Olympic sport. These athletes, at least, are prepared to compete at an Olympic level next to the Luxor Hotel & Casino pool as hosts Rob Riggle and Nikki Garcia look on from a safe distance.

Stonie is, for the record, here as yet another Major League Eating contract-dispute refugee, and he’s also the only Nathan’s competitor to have ever broken Chestnut’s winning spree. (It was in 2015, the year that Chestnut’s fiancée broke up with him, a fact that the Nathan’s announcer would publicize at the hot-dog-eating contest one year later—but we’re here to count wieners, not traumas!) Stonie now makes competitive eating content for his 16.9 million YouTube subscribers, and it is my greatest hope that he gathered Joey and Kobi into his greenroom at some point to talk monetization. The $100,000 cash prize on the table today is a mint to be sure, and $90,000 more than Nathan’s awards annually, but it doesn’t have nearly the same replenishment rate as 16.4 million YouTube subscribers ready and willing to watch a relatively small man who has a jaw that looks like he swallowed a ruler eat 24 Popeye’s biscuits simply because he can.

Anyway, all I can think while watching Stonie strip and eat 53 chicken wings with a surgeon’s precision and a bear’s determination to double its body weight before hibernation is: “That was only three minutes. And it was the most insane physical feat I’ve ever seen in my life. Joey and Kobi have to do it for 10.”

There is a common refrain among people just tuning in to competitive eating that goes something like: “I think I could do that.” And if you are one of the people thinking that right now, I want to hold your hand when I tell you this: No the fuck you could not. While there is absolutely nothing more American than simply looking at something and feeling sure that you deserve to excel in it, let me break this down a little: Competitive hot dog eating is a sport where you have to do the single hardest part of it for 10 minutes straight. It is both a marathon and a sprint, as well as an attempt to constantly convince your mind and body that they should work together to do something they both know they should not be doing.

An eater like Kobayashi or Chestnut can average about one hot dog every eight seconds. Which almost seems like enough seconds to quickly stuff one hot dog into your mouth by sheer force of will—but now factor in biting and swallowing. That’s basically a bite and a swallow every two seconds. In the show’s pregame, as a woman named Leah Shutkever eats five-plus pounds of watermelon in 153 seconds like she’s Ms. Pac-Man chomping dots, a chyron flashes across the screen: “Leah has the ability to bite and swallow at the same time.” The crowd giggles at this reveal, but think about it. Better yet, try it. Sometimes, you don’t even know you don’t have an ability until someone else shows you that they do—then they show it to you for 10 minutes straight.

At the corner of Surf and Stillwell Avenues on New York City’s Coney Island stands the original Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs, touting more than 100 years in business with a hot-dog-shaped sign surrounded by enough fluorescents to safely lure any number of tourists and locals toward its frankfurters 13 hours a day, seven days a week. The building that now sprawls across the full extent of a Coney Island block started as a nickel hot dog stand in 1916, when Nathan Handwerker and his wife, Ida, took out a $300 loan to launch their American dream on a stretch of counter 5 feet wide and 8 feet deep. “Hot dog is an immigrant food, invented by immigrants, sold by immigrants,” Bruce Kraig, an emeritus professor at Roosevelt University who specializes in food and hot dog history, told Business Insider in 2020, referring to hot dogs as a singular unit in a way I didn’t actually know was possible.

Europeans have been consuming sausages for centuries, of course, but hot dog legend states that it’s the placing of that sausage inside a bun that’s a solely American invention. The earliest known establishment to sell a be-bunned sausage was Feltman’s, a giant restaurant on the Coney Island boardwalk that would eventually become recognized as the largest restaurant in the world. But sometime around 1912, they hired a young Polish Jewish immigrant named Nathan to slice buns for their “Coney Island red hots,” as the hot dogs were known then. A few years later, Nathan took their idea just a few yards down the boardwalk, undercut their prices by 5 cents, and began selling the Coneys that would make him, his product, and a bunch of other people with superhuman stomachs a titular level of Famous.

This much we basically know to be true about the not-so-humble origins of Nathan’s Famous. The rest of the hot dog’s mythology, and how it became so inextricably tied to screaming, “USA! USA!” once a year, have a slightly looser relationship to reality, if you’re at all particular about your reality being “true” over, say, “fun.” Jamie Loftus, author of Raw Dog: The Naked Truth About Hot Dogs and star of the 2022 one-woman show Mrs. Joseph Chestnut, America USA tells me that “the most American thing about the hot dog is that it’s the success of a pretty made-up marketing narrative.” We are, at our country’s very core, just Don Draper, four fingers of lunch scotch deep, standing next to a posterboard with a cartoon hot dog drawn on it and pitching gorgeous nonsense.

One early 20th-century marketing legend said that it was a British fella who brought buns and wieners to the American masses when he had the bright idea that something warmer than ice cream would go over better at chilly baseball games. If you ask the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council, they’ll tell you a tale about a German immigrant who handed out gloves in order for his customers to eat street sausage—until someone was like, “Hey, what about a glove that you can eat so everyone will stop stealing all of your gloves?” And you know someone was hawking a 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair origin story. “From what I can tell, they’re all made up,” Loftus says. “But all of these stories embody this very American narrative of ‘One day, this normal American guy had this amazing idea, and it changed the world.’” She compares it to the American dream mythology, that everything needs to be Bill Gates building a computer in his garage—an uncommon genius pulling himself up by his bootstraps with no breaks, no windows, and no systemic issues that could ever get in his way. Just pure, hard, American work …

In truth, the collective mythology of the hot dog—that immigrants brought over their national food traditions, they adapted them to the grab-and-go culture of their new home, and it slowly spread across the nation, picking up local idiosyncrasies and delicious subcultural flair (except for you, Chicago, you went too far) and nourishing poor people during times of economic crisis—is an equally American story, and surely a more honest tale. “But that’s not a sexy story,” Loftus says. “And it doesn’t make anyone any money. So that’s not the story people are interested in.”

And if there’s one thing Nathan’s has sustained through a century of grinding out glizzies, it’s a narrative that people are interested in. But over the decades, that tradition of prioritizing a good story that yields a great paycheck over what might technically be classified as the truth would grow and morph in ways Nathan Handwerker could surely never have imagined. Although, when I think about another maybe-true story I heard about Nathan—that he hired local hospital workers to wear surgeon smocks and stethoscopes and eat at his counter next to a sign that said, “If doctors eat here, it has to be good …”—I realize that he may have been able to predict exactly what and who would rise up from that hot dog counter. I mean, he named it Nathan’s Famous.

If you can believe it, this whole thing kind of starts with a guy named Mortimer “Morty” Matz. Matz created the Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest as a marketing stunt in the 1970s when he took over the Nathan’s account at his PR firm. As part of that narrative, he also said that the Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest was created in 1916, when a handful of immigrants decided to speed-eat hot dogs to determine who was most patriotic. He later said that the only years the Nathan’s contest wasn’t held were 1941 and 1971, when they were canceled as protests against World War II and the Vietnam War.

But Matz fessed up in a 2010 New York Times profile that the hot-dog-eating contest wasn’t ever a protest against anything, except maybe against not getting enough attention. (Another of Matz’s famous clients is the Durst Organization … which actually might explain a lot.) Matz simply created the hot-dog-eating contest as a way to promote Nathan’s hot dogs on the holiday that hot dogs had become most associated with—iconic marketing stunt behavior that would ultimately be passed down through enough generations to cause serious harm to a young Japanese competitive eater’s emotional well-being. But we’re not quite there yet.

First, Matz had to pass the marketing stunt baton to George Shea and his brother Rich. It became their job to make hot dogs—technically tubes of mismatched meat, intrinsically tied to poor labor practices—as appealing to the public as possible. So George came to call on what was naturally at his disposal: the pro-American rhetoric that’s also intrinsically tied to hot dogs, along with his ability to spin any nugget of a story into a fool’s gold spectacle. “I started working with Morty Matz in 1988, and Jay Green ate 13 hot dogs and buns to win,” George tells me as we chat about the origins of competitive eating. “There were no competitors; there was no such thing as competitive eating,” he says. “It wasn’t called that. We never even bought that URL because we were the only ones who called it competitive eating.”

When George officially took over the Nathan’s Famous account—and the Nathan’s Famous competition—in 1991, there were a few dozen people gathering on Coney Island to watch the contest each year, and two TV cameras recorded the briskly paced hot dog eating. By 1997, the Shea brothers had organized competitive eating into a sports league, and by 2001, an international wunderkind named Takeru Kobayashi had nearly doubled the American hot-dog-eating record in his Nathan’s contest debut. Television’s largest sports network, ESPN, came calling a few years later. Kobayashi completely dominated the sport until 2007, when an estimated 50,000 people gathered to watch him struggle through a “reversal of fortune” (use your imagination) as the sport’s next wunderkind—and Nathan’s preferred champion—Joey Chestnut outate him by three dogs. In 2012, before Netflix had even aired its first original series, let alone considered broadcasting a hot-dog-eating competition live on its streaming platform, George Shea introduced Chestnut at the Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Eating Contest thusly:

We kneel at the side of the road to be covered in the dust from the hooves of our enemy’s horses and we chew on gravel and we smile the smile of broken teeth and supplication, but one man will not yield! One man will stand over it, and he will cast you in his shadow! Because the rock on which he stands IS NOT A ROCK! It is courage! It is hope! Enough to sustain a nation! He will howl at the moon, and he will call his name into the new day to put his claim! Ladies and gentlemen, the no. 1–ranked eater in the world … he has God’s username and password, and he does with it what he chooses. The Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Eating champion, JOEY CHESTNUUUUUUUUT!!!

Two years later, 2.7 million people tuned in to ESPN to watch Chestnut eat 61 hot dogs in 10 minutes; then, in 2021, he set the reigning Nathan’s Hot Dog record with 76 hot dogs and buns eaten.

And by 2024, Kobayashi and Chestnut were both completely absent from the Nathan’s Fourth of July contest due to respective contract disputes, fleeing to the loving—if perhaps brief—embrace of television’s largest streaming platform and leaving behind one major-league-sized question: How did competitive eating go from marketing stunt to a legitimate organized sport to a ship sinking under the weight of its own consumption?

Labor Day 2024

40 Minutes to Hot Dogs

Truly, there’s nothing like the sights, sounds, and smells of a casino in the morning. But today, visitors to the Luxor are in for a truly novel picture: a line of people snaking around the slot machines and past the Titanic artifact exhibit who are predominantly dressed as some variation of a hot dog. As it turns out, there are many kinds of hot dog suits: with and without ketchup; over the head or just to the shoulders; with Hamburger Helper gloves vs. without; always with mustard; always a huge hit. The line’s many hot dogs pose for pictures with strangers that will soon be blasted out to group chats while they wait to get inside. Unfinished Beef is technically a ticketed event, but the tickets were free and by request, so the crowd ranges from competitive-eating enthusiasts (including actual eaters, like Eric “Badlands” Booker and Patrick Bertoletti, who reigned supreme at this year’s Chestnut-less Fourth of July Nathan’s competition with 58 dogs) to Vegas locals curious about the spectacle.

But whether they’re a longtime fan or future fan, ketchup wearer or not, the phrase on everybody’s lips is: no dunking. Two decades after Kobayashi brought his patented wiener-snapping, bun-dunking methods to the United States, completely changing the way that people competitively ate hot dogs, he’s hit the reverse button. In contract negotiations, Kobayashi insisted that wieners had to stay in buns and be consumed as a whole hot dog—with no dunking, there would be “nowhere to hide,” as Kobayashi said at the Unfinished Beef press conference. But as visions of Nathan’s contests past dance in their heads, these Netflix-assembled fans are wondering whether no dunking will simply mean fewer dogs eaten. Predictions range from the low 50s to the high 60s, but no one in the crowd is predicting a broken record without the slippery effects of wet, wet bread.

When I caught up with Chestnut and Kobayashi in their respective greenrooms the day before the competition, Kobayashi was sporting—if you’ll excuse the generational vernacular—a fuck ass bob. It was the chicest shit I’d ever seen. As the contest begins, he has revealed a dramatic buzz cut—a piece of gameplay I can’t entirely comprehend, but I am not a hot dog athlete—coupled with a silken boxer’s robe that he throws off dramatically to reveal a sleeveless muscle tee as he approaches the hot dog altar. He really is a rock star.

Chestnut, meanwhile, ambled into that press conference the day before wearing the same standard “TEAM JOEY” white T-shirt that Netflix hands out to precisely half of the live crowd the day of the contest (the other half is in black “TEAM KOBI”), except his sleeves were emblazoned with the Dude Wipes logo. “Yeah, Dude Wipes are extremely refreshing,” he responded shyly when asked about his sponsored accessory of choice. (Like most of us, he’s much bolder on social media.) By showtime, he’s upgraded to an athletic jersey of sorts, also sponsored by Dude Wipes.

I love getting ready to put an obscene amount of food inside of me.Joey Chestnut

Both of them embody their archetypes within the sport they’ve built up, wiener by wiener. Chestnut: the everyman. Kobayashi: the artist. And they both made it here by some combination of precise training and the innate motivation to hoover down 18,000-plus calories in 10 minutes. Chestnut feels like he was nurtured into being a superior eater because he learned to eat quickly among his hungry and competitive siblings, but he’s certain that there are some natural elements that help the best eaters, too: “Oh, big head? Yeah, a big head helps you a lot … natural eaters just have a crazy big head and esophagus.”

It’s during the course of Unfinished Beef that I come to understand this one undeniable truth: Competitive eating is the only sport where the athletes train their organs. They stretch their esophagi by swallowing upside down on benches, they expand their stomachs by drinking gallons upon gallons of water, they do tongue exercises and larynx yoga, and they learn how to force their Adam’s apples up and down to move food down their throats faster. They work out their jaws, their necks, their abs. Chestnut smushes his tummy around like a Beanie Baby to move the food throughout his general torso area, and Kobayashi is known for his Kobayashi wiggle to, well, wiggle upward of 60 hot dogs around in his small frame. Ahead of a match, they fast for days and keep an extremely clean, mostly vegetarian diet. Chestnut monitors his meat consumption on an annual basis the way you or I do on a day-to-day basis. “One of my biggest splurges is my doctor,” Joey told Wired ahead of the race. In his competitive-eating career, Joey has consumed around 335,000 calories in hot dogs—about the same number of calories the average person eats in six months.

“I love getting ready to put an obscene amount of food inside of me,” Joey tells me without an ounce of irony. “It’s what I love doing.”

The first recorded history of competitive eating goes all the way back to the 17th century, when a farmer named Nicholas Wood began to do things like eat seven dozen rabbits in one sitting, as recounted in Jan Bondeson’s book The Two-Headed Boy, and Other Medical Marvels. Rather than competing against a rival, however, Wood—a.k.a. the Great Eater of Kent, a.k.a. the Kentish Tenter belly, a.k.a. the Most Exorbitant Paunchmonger—was competing against food itself. He was simply trying not to go into a literal food coma or lose all but one of his teeth from eating an entire mutton shoulder (failed on both accounts, unfortunately).

Three centuries later in America, the quantity of food couldn’t compare to Wood’s competitive eating, but the nicknames were holding up. In 1991, when Frankie “Large” Dellarossa won the Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest, he beat 19 other contestants by eating 21 hot dogs and took home a 3-foot plastic trophy. “In the early years, I did it for fun,” George Shea tells me. “We weren’t making any money. Even in ’97, ’98, ’99, 2000, 2001, we were not making any money.” George began calling every publication and radio station that would answer and telling them about the athletes competing in the Nathan’s Fourth of July contest to get a rise out of them. They couldn’t believe anyone was calling competitive hot dog eating a sport, but also—they were listening.

In the 30 for 30 documentary about the lost rivalry between Kobayashi and Chestnut, The Good, the Bad, the Hungry, George says that to create a sport, you need a backstory, and the greatest example of creating such a backstory was when he bejeweled a weight-lifting belt to create a WWE-style “Mustard Belt” on the floor of his apartment in 1996. George proclaimed that the belt was “created by the descendants of Fabergé,” that it had been lost to Japan years ago, and that the United States needed to get it back. “Everything was a self-fulfilling prophecy,” George says in the documentary. “If we said there was a championship belt that was lost in Japan, there was. If we said we had a rivalry with the Japanese, there was. If we said we had a circuit of events, there was. And everything sort of just came true.”

With the Shea brothers circulating the news that this was a real sport with real events, they did actually have to fulfill their own prophecy at certain points. “We realized we had a sport, but we did not necessarily control that sport, so we quickly got organized and got all our eaters together in a league.” In 1997, they created the International Federation of Competitive Eating, which became the parent company of Major League Eating, the sanctioning body that now oversees, regulates, and organizes most competitive-eating events and TV deals in the United States, including the biggie, the Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Eating Contest on ESPN. “It just grew and grew, but there was no plan other than to make my brother Richard laugh or the journalists laugh or the crowd laugh,” George says of accidentally sanctioning an entire sport that’s spanned three decades—in the process of advertising a hot dog brand. “Everything was a PR push, and the goal was PR media exposure. And the reason we did everything was because we thought it was interesting and funny.”

And he’s right; it was interesting and funny. It still is, even if you can see the conflict of interest train coming from a mile away. George shows me a glass jar on his desk: “I have Jim Mullen’s teeth, the original teeth of Jim Mullen right here preserved in a seltzer.” Mullen was the winner of that great, definitely made up 1916 immigrant hot-dog-eating contest that Matz told The New York Times about in 2010. Preserved in seltzer—and on this Zoom recording—forever.

If a stunt falls in the woods and no one cares, is it just a harmless piece of narrative lore? If a butt fills the seat, a competitor wins the belt, and Nathan’s Famous gets its name splashed across the front page of the L.A. Times, is the PR machine working for all parties involved? Over the course of the 30 for 30 documentary, Haimes slowly reveals George to be a slightly unreliable narrator. George also reveals himself to be that, saying early on, while barely holding back a laugh, “A lot of what I say is not literally true in terms of words, but it is emotionally true.” He says this while standing in front of a framed newspaper article that reads, “Girl starts 21 day sit-on. She’s trying to hatch an egg.” It’s presumably one of his earlier PR stunts, though I don’t know which egg brand he worked for.

We are hardwired for narrative, and it’s usually very simple: the black hat and the white hat, the heel and the babyface.George Shea

Despite George’s discontentment with how he was portrayed in that documentary, Haimes told me that she does think of him as a kind of genius. “He recognized the glee and the interest audiences have in this endeavor. I think what he and his brother Rich Shea did was extraordinary. In all these years, from the time they began in the late ’90s to now, creating an institution where when somebody has hot dogs on the Fourth of July, you think about Joey Chestnut and you think about the hot dog contest.”

If you’ve watched a Nathan’s Fourth of July contest even once, you also think about George. Outfitted somewhere between a carnival barker and a tent revival preacher, waving his arms from a Nathan’s-branded pulpit, affecting some version of a transatlantic accent, exalting the start of the contest with “They say that competitive eating is the battleground upon which God and Lucifer wage war for men’s souls, my friends. And they are right.”

Loftus attended her first Nathan’s Coney Island contest in 2021 and was blown away by the energy. “Everything was at an 11. It was this very knowingly theater piece, and it feels like George Shea—I mean, he’s doing a Vince McMahon impression. And if I’m recalling correctly, his wife has worked for soap operas and the WWE.” She is recalling correctly, and while George swears he’s never watched much wrestling, he does agree with the comparison insofar as he sees both sports as necessitating a certain level of storytelling to capture the audience. “What we did with the intros was independent of [WWE], but it is a natural consequence of the human need for narrative,” he says. “We are hardwired for narrative, and it’s usually very simple: the black hat and the white hat, the heel and the babyface. It actually demonstrates who we are and our limitations … it’s just good versus bad.”

He’s right. But as the voice of MLE, he’s also had a disproportionate amount of control over shaping competitive eating’s narrative. In 2016, George told The New Yorker that the best introductions should “ride the razor’s edge between joking and not joking.” Three days after the article was published, he told a crowd of 30,000 people and millions watching at home that the year before, Chestnut’s fiancée had broken up with him one week before the competition: “And then on the Fourth of July, he lost the title of world champion. And he was beaten, and he was broken, and he was alone. And nothing that he owned had any value, and his thoughts had no shape and no meaning, and the words fell from his mouth without sound. And he was lost and empty-handed, standing like a boy without friends on the schoolyard.”

Presumably, Joey was on board with these public divulgences. But in competitive eating, as opposed to WWE, it’s hard to know exactly who’s signed up for what and when they signed up for it. What started as a publicity stunt turned into a popular cultural absurdity, which turned into a bona fide sport with real competition and athletes whose feelings, careers, and crafts must be taken into account. “We did not say, ‘What cultural niche has not been exploited?’” George says of the unexpected fame and escalation around competitive eating. “It was just, we worked for Nathan’s. There was this opportunity, and then it grew and grew.

“And then what happened when Kobayashi and Joey came is that it really morphed from a cultural absurdity … into a sport.”

When he was 22 years old, Takeru Kobayashi ate 16 bowls of ramen in one hour to win the Japanese variety show TV Champion. In 2000, he ate 8.9 kilograms over the course of competing in Food Battle Club, besting his mentor, Kazutoyo “The Rabbit” Arai. The young Kobayashi wept after the win because, in that moment, he realized that becoming the best eater in Japan meant surpassing his mentor. “When I started going on TV, I thought it was a joke,” Kobayashi says in the 30 for 30 documentary. “People saw the eaters as freaks, but I learned they were actually very serious, so I developed a respect for them. And I thought, this is a sport I wanted to do until the day that I die.”

In the United States, George Shea was prepared to market Nathan’s hot dogs until the day that he died. But MLE had yet to obtain a champion worth rooting for in its quest to get competitive eating to take off. In 2001, Major League Eating invited Kobayashi and a handful of other Japanese eaters to participate in the Fourth of July contest. Kobi was only 23—he was skinny, he didn’t speak English or know much about American culture, and the local press showed little interest in him ahead of the race … and then he broke the American record of 25 hot dogs with nearly nine minutes still remaining on the clock. Kobayashi ate so many hot dogs that they ran out of official laminated numbers to flip and scrambled to write new ones with a marker. In 12 minutes, he doubled the American record, eating 50 hot dogs and changing the course of competitive eating forever. “Before Kobayashi became so prominent in the Nathan’s contests, it was sort of presented as ‘Oh, this is just a very American excess, really hungry guys kind of thing,” Loftus says. “Kobayashi revolutionized the sport in the U.S.”

The Shea brothers may have made competitive eating an event in the United States, but Kobayashi made it a sport. He trained like an athlete. He invented most of the techniques we still see used in competitive hot dog eating to this day, most notably the Solomon method of snapping the hot dog wiener in half and eating it as you dunk the bun in water. (The term for this method, however, was created by hot dog evangelist George Shea, after the parable wherein King Solomon threatens to split a baby in half to reveal the most deserving victor between two rivals—how topical!) Most importantly, Kobayashi ate a lot of hot dogs, winning the Nathan’s contest for six consecutive years as his star continued to rise in the United States. ESPN began broadcasting the contest live in 2004, when Kobayashi set a new personal—and world—record of 53 hot dogs eaten in 12 minutes. To quote one of George’s introductions for Kobayashi when he was still MLE’s most viable hero: “The rules of the universe do not apply to the 144 pounds that comprise Takeru Kobayashi. He is an alchemist who has transformed athletics into mathematics, mathematics into poetry, and poetry into history.”

But Kobi didn’t see himself as a magician or an artist only—he saw himself as an athlete and an innovator. “I came to America to follow my dream,” he says in the doc. “I thought of myself as someone creating a new sport.”

Seeing his unparalleled, unprecedented dominance, the Sheas began unleashing Kobayashi onto newly minted televised MLE events like the Alka Seltzer U.S. Open and the Glutton Bowl, where, in a truly superhuman feat, he ate 17.7 pounds of cow brains. “Kobayashi and the MLE were growing on parallel tracks, both helping each other,” George says of the soaring period between 2001 and 2006. But George had always riddled the Nathans’ contests with pro-American rhetoric. Of his famous storytelling around the missing Mustard Belt, George says in the documentary that “everything just became enormously fun: How can the Japanese guy beat the American? America’s honor besmirched, dark days for our country! And that’s where things got off and running.”

When Kobayashi won the 2004 Nathan’s contest, George said to him, “There is nothing greater than the belt, the victory, and the trophy. Even though it wasn’t an American who won—congratulations.” It’s unclear whether this was translated for Kobayashi, but he’s said that the language barrier made him less aware of what was happening in the culture of the sport that he was building up brick by brick, bun by bun with his unparalleled skill and showmanship. While he was becoming an American icon—he was dominating the competitive eating of hot dogs, those little freaks of American nature, for goodness’ sake—MLE was just waiting for an American who could beat him. Because, to this point, Kobayashi had been bested by only one opponent: a 1,089-pound Kodiak bear who claimed no home country on the TV show Man Vs. Beast.

When that episode aired in 2003, Chestnut was watching at home. And he thought what so many people do when they watch competitive eating: “I think I could do that.” More importantly, he thought, “I think I’d like to do that.” He began training with his mom and brother and qualified for the 2005 Nathan’s Fourth of July competition by winning a local asparagus-eating contest. Or, as George put it to me more narratively: “He was a rookie out of the asparagus circuit.” That rookie placed third in his first Nathan’s competition, eating 32 hot dogs and buns in 2005. In 2006, he grew that number by 20 to take second place after reigning champ Kobayashi’s 53.75 hot dogs. George was somehow salivating more than the both of them.

And here we’ve arrived at the most exciting time competitive eating has ever known—when eating actually became competitive. Haimes tells me that, in the early days of their rivalry, the differences between Kobayashi and Chestnut were stark: “Kobi approached things quite artistically. He’s really an aesthetic and a visual guy. He’s more of the poet of competitive eating, if Joey is the everyman.”

In her documentary, Chestnut told Haimes that the person he wanted to emulate was always Kobayashi. “I ate way more herky-jerky, and Kobayashi ate way more graceful. Kobayashi sees it as almost an art.” Naturally, these adoring words are spoken over a montage of Kobayashi shoveling spaghetti, salad, and spinach and artichoke dip into his mouth while he bested Joey in a competition in 2005. “I think, in his younger days, Joey had a very single-minded vision of wanting to beat Kobayashi,” Haimes tells me. “I do believe that Joey respected Kobi. But there was a point—and he said this on the record—where he came to kind of hate him. Where he really was thinking about him at night: How does he do it? What’s his greatness? How come he can eat so much? How can he continue to beat me? It’s easy to see how that obsession can tip into extremely strong feelings.”

And for the best athletes, strong feelings turn into legendary performances. Chestnut trained, he ate hundreds of hot dogs at home in San Jose, and he began to see Kobayashi no longer as a god he wanted to emulate, but as a competitor he had to annihilate. In their 2007 Nathan’s showdown, even though Kobayashi ate 10 more hot dogs than he had the previous year, Chestnut ate even more: 66 hot dogs in 10 minutes to Kobayashi’s 63, putting an end to one hot dog dynasty and starting a new one. When Chestnut earned his first of 16 Nathan’s championships, MLE finally had what it wanted most: an American hot dog prince.

With that came the abrupt narrative heel turn of Kobayashi. Going forward, at every Nathan’s contest he entered he was the foreign villain, coming to steal the belt back from the United States. “I could feel the crowd becoming aggressive toward me,” Kobayashi said of his first loss to Chestnut. “I started to feel threatened that they might do something to me when I got offstage. I didn’t understand American culture, so it scared me.”

The Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Contest hadn’t been designed to support two narrative heroes. It hadn’t really been designed to become an entire sports league, complete with competitors who trained like athletes and rookies from the asparagus circuit who chased down international superstars. It had been designed … as a marketing stunt for Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs.

In 2008, MLE decided to change the rules to limit the contest to 10 minutes, which resulted in upset among the competitors, who saw the rule change as needless at best, unsafe at worst. “I wish George had been able to think about these people and how much they were training as athletes, the time and energy they’re putting into the sport. To change the time by two minutes, to an athlete, that’s huge,” Kobayashi’s wife and manager, Maggie James, told Haimes. The unexpected time change also resulted in a tie between Kobayashi and Chestnut at 59 dogs, for which MLE somehow had no contingency plan. On and off the boardwalk, MLE seemed incapable of keeping up with the ever-increasing skill and demands of its top athletes. Kobayashi, formerly the league’s top draw, was also beginning to feel uneasy about his restrictive contract. “My whole ability to eat professionally in the United States was exclusively owned by Major League Eating,” he says in the 30 for 30 doc. “I couldn’t participate in any TV shows or contests in the U.S. they were not involved in. My contract was crushing my potential.”

George infamously confirmed as much: “The issue is, as someone who’s competing at this from an international basis, you have to understand that there’s an American hero. And you can be a hero in the same exact way, but you can’t be an American hero. Because you aren’t American.”

“As a person who grew up in Japan, Kobi holds quite different rules around competing and honor,” Haimes tells me five years after her documentary first aired. “When his sense of honor wasn’t really respected on the terrain of a competition in America, I think it was hard for him to reconcile. Because we are of our culture.” That culture very much includes hot dogs eaten on the Fourth of July, but also: taking a certain glee in the come-up of a hometown hero, and even more glee in a worthy takedown. “When Joey won, that was a very, very powerful story that America got the belt back,” says George. “And I picked up the flag and got on the table and said, ‘USA, USA’ or something like this. That, apparently, according to the documentary, was very offensive and hurtful to Kobayashi.” George says he would have never done it if he’d known. He would have apologized. He didn’t mean it that way. “I was just playing with emotion. … It never occurred to me that he would take it in that way.”

Of course, the great power of narrative is that it’s subjective—once a story is out in the world, we no longer have the control over how it’s received that we once had in crafting it.

Kobayashi didn’t renew his MLE contract in 2010, and therefore he wasn’t invited to compete in the Nathan’s Fourth of July contest that year. A ban, as it was called by the media. And after being arrested for walking up the side of the stage in a “Free Kobi” T-shirt while attending the contest as a spectator (George insists that Nathan’s never pursued pressing any charges), Kobayashi left the Nathan’s Fourth of July competition for the very last time. In handcuffs.

Labor Day 2024

20 Minutes to Hot Dogs

As Chestnut and Kobayashi descend upon the stage to roars from the crowd, a crew of people in all black are meticulously checking the temperature of the water, buns, and wieners. Dozens of electric kettles have been set up on each side of the stage to keep the players’ water at what is clearly a previously decided-on perfect temperature. Because Chestnut is no longer signed to MLE, we’re allowed to know what name brands are being kept warm in towers of temperature-safe storage bins: Ball Park franks on Great Value buns.

There is a baby in the audience whom I cannot stop watching because I cannot believe she’s sleeping through the constant chants of “Jo-ey! Jo-ey!” and “Ko-bi! Ko-bi!” When I spoke to her parents in line earlier, she was also sleeping. Exactly how many hot dogs has this baby consumed? The entire family is wearing hot dog suits, and I have the fleeting thought that, if competitive eating does ever codify so hard that it develops junior circuits, this baby might be just a few years from starting her career. And a few short decades from becoming the next Chestnut. How many hot dogs will the human body be able to consume in 2046? How many chicken wings, or hard-boiled eggs, or lobster rolls?

The mind wanders when waiting for the most exciting 10 minutes of one’s young life.

I will say that anytime actual eating isn’t happening, the broadcast is noticeably missing a little je-ne-sais-George-Shea. Sometimes you just need a man in a hat to tell you why eating hot dogs quickly is akin to the creation story. “This man represents all that is eternal in the human experience,” George once said of Chestnut. “Through the curtain of the aurora, a comet blazes to herald his arrival, and his victory shall be transcribed into every language known to history, including Klingon.”

Soon, I will honest to God agree with him.

Otherwise, the best commentary comes from Tim Janus, whom Nathan’s enthusiasts will know as Eater X, ranked no. 2 in the world by MLE in the not-so-distant past, but whom I first became acquainted with as Chestnut’s partner on The Amazing Race. (He’s also the world burping champion, according to the World Burping Federation—a different niche sports story for a different time.) He says that Kobayashi has been doing two full practices a week for the past six months and, in particular, working on speed runs to get the pace of his first minutes at its absolute highest. “Joey won three contests in a row against Kobi,” Janus says. “If he wins today, there’s no question, he remains no. 1. But if Kobi wins—well, he can change the narrative, but he has to win by more than a few.”

And that’s the beginning of the end.

On June 11, just a few short weeks before the Fourth of July, Major League Eating made a statement that Chestnut, the 16-time champion of the Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Eating Contest, would not be competing in 2024 because he had chosen to “represent another hot dog brand.” Internet chaos ensued. As with Kobayashi in 2010, the word “banned” was thrown around a lot, although it wasn’t entirely accurate. Instead, there was another appropriately dramatic word for what the dispute actually centered on: veganism.

At some point, while MLE was attempting to renegotiate Chestnut’s contract—a source who talks a lot like a Shea brother told the New York Post that Chestnut was paid $200,000 to appear in the Nathan’s contest in 2023 and was offered a four-year, $1.2 million contract going forward—he informed them that he had signed as a spokesperson with Impossible Foods, which includes a line of meatless hot dog franks. “I really thought that it wouldn’t be an issue at all,” Chestnut told the GoJo and Golic podcast a few weeks after the news had come out. “In my contract with Nathan’s and with Major League Eating, it lists a bunch of companies I can’t work with, and it lists these characteristics of companies that I can’t work with. Even Nathan’s, they were like, ‘Yeah, they weren’t really on the list before.’”

Chestnut either could not or was unwilling to unsign with Impossible; the result was that he didn’t re-sign with MLE, which either could not or would not budge on a vegan clause for Joey’s contract.

Chestnut tweeted that he was “gutted to learn from the media that after 19 years Im banned from the Nathan’s July 4th Hot Dog Eating Contest. I love competing in that event, I love celebrating America with my fans all over this great country on the 4th and I have been training to defend my title.”

Invoking a different patriotic symbol, George Shea told ESPN of Chestnut’s contract decisions: “It would be like Michael Jordan saying to Nike, ‘I’m going to represent Adidas, too.’” Which is a compelling argument, to be sure, but it grandly ignores that the sport of competitive eating in the United States, to this point, has been almost entirely sanctioned and organized by a league that is directly tied to one brand. So I’d counter that it’s a little more like saying, “Michael, you can’t play in the NBA because it’s sanctioned by Nike. And neither one of us is gonna pay you Adidas money.”

Immediately following the news that Chestnut was a free agent, chatter took off among fans that Kobayashi should come out of retirement for one last non-MLE hot-dog-eating face-off. Wouldn’t that be amazing? Wouldn’t that be an unbelievable conclusion to their unfinished rivalry? Wouldn’t that be like if Michael Jordan and LeBron James played a televised game of 21, and Nike and Adidas had nothing to do with it?

Except that in this world—the world where competitive eating is definitely a sport that’s been codified, trained for, and built up into a league of serious athletes over the past several decades, but also super is not the NBA—that kind of thing can actually happen. Kobayashi may not be able to feel physical hunger anymore, and he may have “retired,” but as Chestnut, his fiercest rival and closest equal, told me the day before facing him again for the first time in 15 years: “Champions like him who are that good? They don’t retire. He’s still got a lot of eating left in him.”

I thought, well, if he doesn’t have respect for me, then I don’t think I want to compete against him.Takeru Kobayashi

Twenty-four hours after MLE cut ties with Chestnut, a press release arrived in my inbox, seemingly pulled together from thin air: “UNFINISHED BEEF: Joey Chestnut and Takeru Kobayashi to compete in winner-takes-all hot dog eating contest, live on Netflix on Labor Day.” The location was TBD. The time was TBD. The graphic used across social media was blatantly made by AI. But can you blame them for rushing? It was an incredible power move for Netflix to strike while the attention iron was hot and make it appear that it’d managed to convince two notorious rivals to face off the moment they became contractually available.

But it was an illusion. Because there’s another thing Netflix has in common with Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs: a long legacy of talented PR men who know how to capitalize on the moment and sell a story to the media. (Except, in my experience, they’re mostly PR women, they run a hot dog contest like the navy, and as far as I know, they’ve never gotten anyone to sit on an egg for three weeks.)

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from hot dog reporting, it’s that the story captures an audience’s attention first, and the story being told here was that no one can bring together a live event like Netflix. What it did with Unfinished Beef was the opposite of competitive eating’s typical self-fulfilling marketing stunts: It meticulously planned something, and then made it seem like an effortless moment of kismet. Along with Haimes, Chestnut, and Kobayashi, Netflix’s live programming department had been working to bring this rematch together for two years. They simply ran into some incredible timing.

But there was still one speed bump: “When negotiating for this whole thing, Chestnut and I with Netflix, we were talking about the possibility of doing this on Fourth of July,” Kobayashi tells me. That would have meant not competing in the Nathan’s competition in 2023, which Joey refused to do (62 hot dogs in 10 minutes). “So I thought, well, if he doesn’t have respect for me, then I don’t think I want to compete against him,” says Kobayashi. Haimes fortunately managed to rope him back into the deal with Netflix by suggesting that they couldn’t “let the perfect get in the way of the good.” Kobayashi relented and even said that Chestnut could compete in the Nathan’s contest in 2024 if he wanted. They would simply find a different (slightly less patriotic) date for their one-on-one. “But then he was banned from the Nathan’s competition, ironically,” Kobi smirks.

After MLE contracts worked against them for years, a contract dispute finally worked in their favor. Kobi and Joey were at Netflix. And people were excited.

Labor Day 2024

Hot Dogs

Before the buzzer signals the most important 10 minutes of their careers, Kobayashi and Chestnut both spend the final moments positioning their Unfinished Beef–branded cups of water. Two seconds before the cannon, Chestnut holds water in his mouth so that his first dog will be plunged into a mouth lake of sorts. It’s effective. Kobi’s movements are more frequent, but also more controlled.

These are all the things I’m able to observe before I go full id at the hot-dog-eating contest. I’m screaming. I’m changing my allegiances rapidly. I’m watching the baby. (Still asleep!) My face is deranged. I’m like Zendaya in Challengers. When former competitive eater Hitomi Sato (1.09 million subscribers on YouTube) appears on the broadcast screen weeping in Kobayashi’s section, I well up, too, even though I swore to myself that under no circumstances would I cry at the Netflix hot-dog-eating contest. I am immediately swept away by this rapid consumption of glizzies.

And speaking of the speed—it’s unbelievable. In the first minute, Chestnut and Kobayashi have reached their personal first-minute bests (13 and 11, respectively), far outpacing past contests in which they were allowed to dunk. They’ve found new methods to adapt to the new rules, which include basically throwing water into any crevice in their mouths—or rather, their whole entire faces—that is not subsumed by hot dog.

For the first minute, they’re in a dead heat. By the second minute, Chestnut is four dogs ahead, a small lag that Kobayashi is able to hold for several of the mid-contest minutes. But Chestnut does not let up once. Whereas Kobayashi is using two hands to stuff the hot dogs in his mouth—perhaps a leftover physical habit from years of the Solomon method—Chestnut finds a hypnotizing rhythm wherein he holds the cup of water in his right hand and slams dogs into his face with his left hand, which is so large you can’t even see what the clump is in his hand. It could be anything.

But it’s not anything—it’s hot dogs. Fifty-one hot dogs by minute five, 66 by minute seven, and with a minute and 10 seconds left on the clock, Chestnut breaks his own personal record of 76 hot dogs. Kobayashi breaks his personal best with 40 seconds left, too, but it’s slightly overshadowed by the fact that Chestnut just hit 80 hot dogs, an entirely new benchmark for the sport. Kobi wiggles; he chomps; he throws water in his face. But it’s not enough. Chestnut eats 83 hot dogs to Kobayashi’s 67, with one hot dog subtracted from Kobayashi’s total after the extremely official weighing of leftover crumbs. The close-ups of Kobayashi’s friends and family section are heartbreaking—pride and sorrow all wrapped up in a community of faces, many of whom are also sporting fuck ass bobs. Somehow, his black shirt appears to glitter in the spotlight, but I know that, in reality, it’s just covered in bits of wet bread and beef.

The winner of the first Netflix Unfinished Beef hot dog competition is Chestnut by a mile—or about 42 inches of hot dog, as it were. He’s broken his own record. He’s beaten his fiercest competitor. He’s been presented with a WWE-style belt by a masked wrestler named Rey Mysterio. So, what now?

Chestnut’s and Kobayashi’s immediate futures will be consumed by the digestion of the 20,000-ish calories they just ingested, give or take a few dogs. It usually takes about five days to get back down to their normal weight after a contest, and there’s a serotonin crash that comes with taking in and releasing all those chemicals. I can relate to the feeling as I walk out into the actual Las Vegas sunlight after 10 of the strangest, most riveting minutes of my life.

After the contest, while Haimes and I are trying to crack precisely why we find competitive eating so fascinating, she can’t stop thinking about a story a boss told her years ago when she was a young production assistant at National Geographic. “My boss came back from Africa, and he told a story of watching lions hunt gemsbok,” she says. “And the lions would run, run, and the gemsbok would run, and the lions would run, and the gemsbok would run. And eventually, there would be a straggler, and the lions would run up and pull down the straggler. And the most interesting thing about it is that the gemsbok didn’t continue to run. They actually stopped and crept back closer to watch the lions eat the gemsbok.”

There’s something so primal yet so culturally moderated about the deeply human act of eating. We all do it, we have to do it, we’re consumed by it—what’s next, how will it affect my body, how will that effect on my body affect my mind, can I do it with my hands, what’s next, can I do it more, can I do it less, what will people think, WHAT’S NEXT? “Eating is one of the great psychic preoccupations of our species—it’s right up there with sex and death,” Jason Fagone, author of Horsemen of the Esophagus: Competitive Eating and the Big Fat American Dream, told NPR ahead of last year’s Nathan’s contest. “I mean, eating is this animal act that we all participate in to some degree, and this is the most animal version of it. … There’s a pane of safety glass between you and the danger.”

“Why would the gemsbok watch the lions eat the fallen gemsbok?” Haimes wondered, figuring out the answer to her lurking question all these years later. Because when given the opportunity to watch the most heightened behaviors of our species, from the safety of the outside looking in—we will.

The human act of eating done with such abandon is both relatable and repulsive—I nearly cried and gagged in equal measure inside the HyperX Arena. To then curate that subversion into an organized sport breaks down the social norms we’re so dependent on to guide us. And the select few remain consumed by it: Can I do that? Should I do that? How do I do it best? How do I do it with other people? How do I do it better than them? What’s next?

It makes perfect sense, then, for Netflix to capitalize on this strange balance of psychological and social preoccupations coursing through the sport of competitive eating. After all, no one leverages the dramatic, compelling, personality-driven side of sports quite like Netflix. In the past several years, it’s cornered the market on competitive human behavior, narratively willing races and rivalries onto the middle- and back-of-the-pack teams in the Formula One docuseries Drive to Survive and bringing the main character energy of Olympic sprinters to the masses, where they belong, with Sprint. It’s shown us a lot of different professional athletes be vulnerable in a lot of different, deeply unused kitchens on Quarterback, and Receiver, and Break Point, and Full Swing.

Netflix seems to value the story of sport as much as, if not more than, the sport itself. And professional competitive eating is a sport that started with a story. But as much as this pairing makes sense—as much as Chestnut and Kobayashi took the reins into their own hands to raise the standard of their sport, as much fun as this rivalry was to watch and follow as a fan, as much as I absolutely did not cry while watching Chestnut defy all physiological human bounds by eating 83 hot dogs in 10 minutes—it’s really hard to imagine Netflix doing this again without extremely similar, extremely advantageous circumstances. Because Netflix is also in the desperate state of trying to elevate its platform. Netflix is also neck-deep in the highly corporate task of commodifying the human need for community by breaking into live programming. From the company that first brought you streaming, then revolutionized bingeable original programming, now comes … cable?

No, no, it’s not that. “For us, we see [live events] like another tool in our toolbox,” Gabe Spitzer, vice president of sports at Netflix, tells me. “We just want to create conversation, have them feel fun, have them be entertaining, and bring people together for a communal moment.” And is a live hot-dog-eating contest the kind of thing that could bring people together in a communal moment … annually? “I think we want to get through this one and see how it does, but I think there’s always a possibility to do more.”

It’s good to be on Netflix—until, y’know, it’s not. Competitive eating can continue to grow for as long as it creates conversation—ahem, profitable conversation. And with contract disputes and broken records and hot dog babies, it certainly did that this year. Netflix hasn’t released viewership numbers for the special, but judging by less hard metrics like social response and general buzz, Unfinished Beef was a success. If nothing else, it was an advertisement for its other, bigger live events: WWE’s Raw, coming to Netflix this winter! But whether it was a long-term success for competitive eating—for Kobayashi, its godfather, and for Chestnut, its champion—remains to be seen. Netflix could present an opportunity to grow the sport of competitive eating in a way that a league built around a brand will never be able to. But it could just as easily decide that the story is over, the beef is now well and done.

In a sport that can render its competitors incapable of feeling full, I just hope that Joey Chestnut and Takeru Kobayashi are satisfied.