Ever since 2012, when MLB wild-card winners first faced off for the privilege of advancing to the division series, the early days of the sport’s October tournament have been a bit of a guilty pleasure. On the one hand, the stakes in a single-elimination matchup, or even a best-of-three series, are so high that every pitch is important. On the other hand, sending a team home after one or two losses feels more than a tad premature, given the 162 games it takes to get there. Deciding clubs’ playoff fortunes that quickly—in an era when October results have come to define fans’ perceptions of success—feels foreign to baseball, which is both the most tantalizing and the most dismaying thing about this blink-and-you’ll-be-eliminated stage.

In a sense, though, this year’s playoffs offer the best of both worlds: all the pleasure of the baseball bacchanal, without the hellacious hangover. The back-to-back, all-day four-game frenzies that kicked off the postseason featured teams too evenly matched for any great injustice to be done to the losers. On average, fewer than four regular-season wins separated opponents in the wild-card round; the five-game gap between the 91-win Orioles and 86-win Royals was the biggest mismatch. The projections picked sides heading into each series, but based on their records, the favorites were almost indistinguishable from the underdogs. To a lesser extent, the same will be true in the division series, where the Dodgers, Phillies, Yankees, and Guardians await—talented teams, but hardly titans whose toppling would shake the sport to its foundations.

None of this applied to the past two postseasons. In 2022, the Padres’ dismissal of the 101-win Mets in the wild-card round, and the Phillies’ and Padres’ double dispatching of the 101-win Braves and 111-win Dodgers, respectively, in the division series sparked existential questions about the postseason’s purpose. Last year’s wild-card-round defeats of the Rays and Brewers, followed by the division-series demises of the 100-plus-win Braves, Dodgers, and Orioles, rekindled the conversation.

It’s nothing new that anyone can win (or lose) in the postseason: For baseball fans, fretting about playoff formats and complaining about early-round upsets is as rich an October tradition as consuming pumpkin spice or spotting Spirit Halloween. Yet the advent of the 12-team playoffs seemed to supercharge the standard discourse about crapshoots and Billy Beane’s shit. The discontent reached a crescendo with last year’s all-wild-card, 90-game-winner-vs.-84-game-winner World Series matchup between the Rangers and Diamondbacks (both of whom missed the playoffs this year, in a post-pennant double downturn not seen since 2007). MLB commissioner Rob Manfred conceded at the start of that series that the league would need to have “a conversation about whether we have it right,” noting, “Enough has been written and said that we have to think about it and talk about it.”

The league can likely table that talk this October. The postseason’s inherent randomness hasn’t changed; what has is the strength of the teams at the top of the field. As usual, everybody’s beatable, but this year, the vulnerabilities are unusually obvious. In 2024, there’s almost no such thing as a playoff upset.

This playoff parity was foretold by preseason projections, as I noted when I wrote about the “clouded postseason picture” back in March: “It’s just like Joe Morgan used to say—there are no (well, almost no) great teams anymore. What we have instead is an amorphous, mediocre middle. … We’re trying to pin the tail on the playoff team while blindfolded, basically.” I was talking about the pennant race, not the postseason itself—I correctly called that “this might be the year that we finally get a meaningful, three-or-more-team tie”—but one could say the same about October.

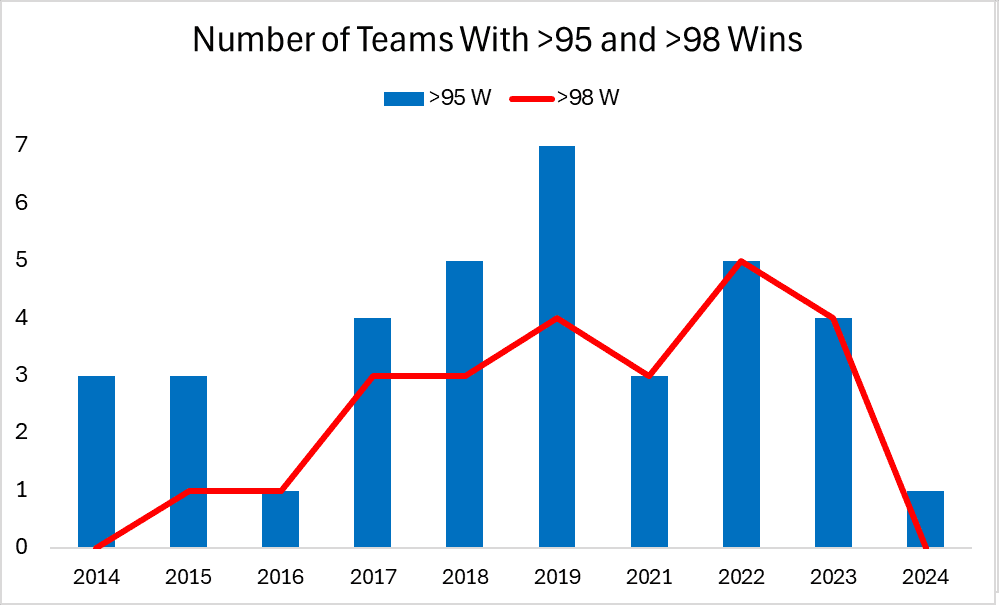

The absence of superteams this season is striking in relation to the past decade. The Dodgers led the majors in 2024 with 98 wins, marking the first time since 2014 that no one won 100 or more. The Dodgers were the only team to top 95 wins, and for the first full season in half a century (since 1974), no American League team even reached that mark. The graph below, which excludes COVID-shortened 2020, shows the number of teams to top 95 and 98 wins, respectively, in each of the past 10 seasons, making clear that this year is a dramatic deviation from recent norms.

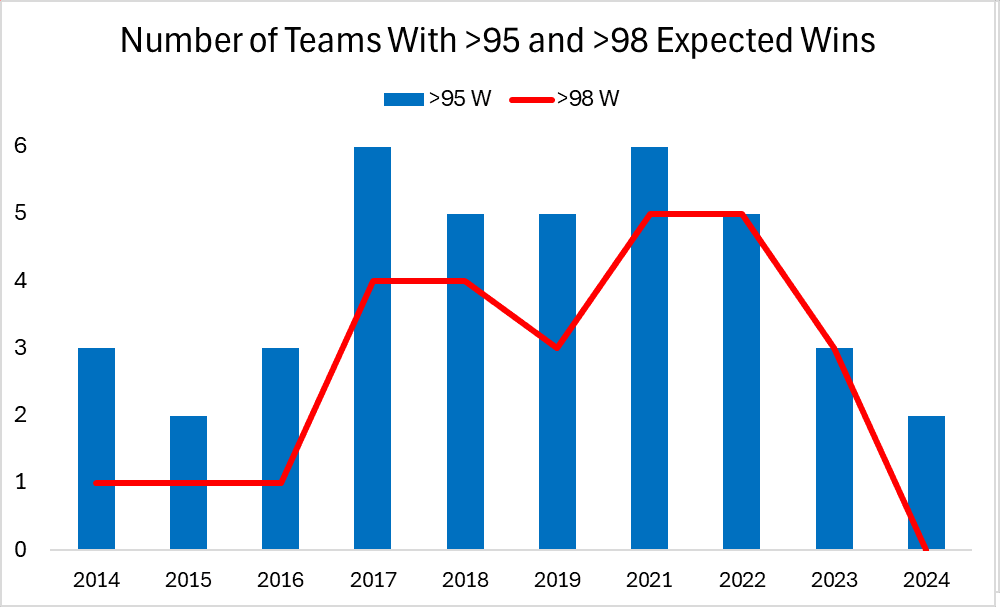

If we go by Pythagorean record, a slightly less luck-dependent measure of team quality based on runs scored and allowed, then this season’s lack of standout teams, um, stands out even more. The Dodgers and Yankees paced the sport with 96 expected wins, the lowest leading total since 2012.

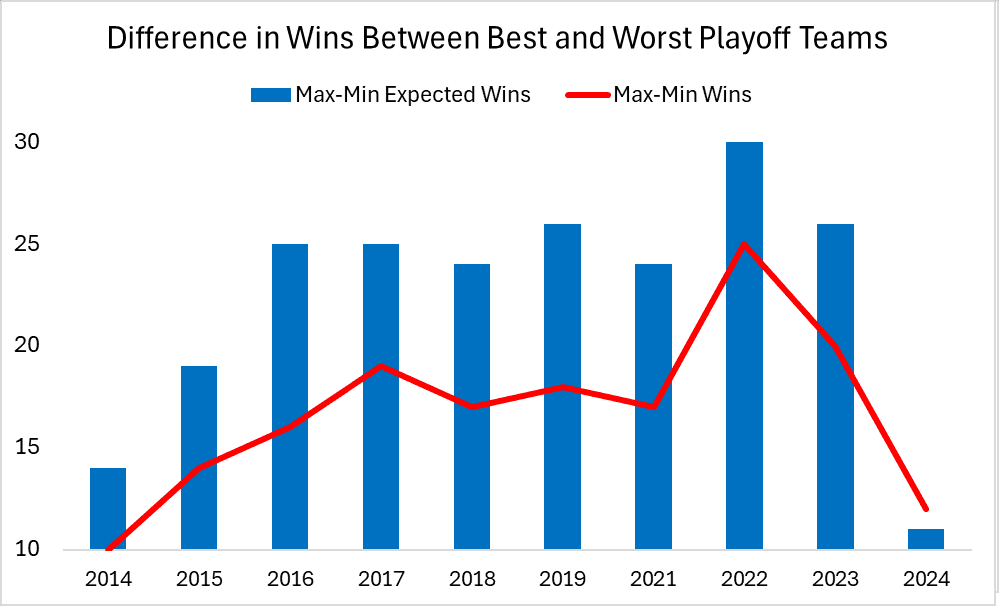

Even in a typical year, there’s a limit to how lopsided playoff matchups can be—there aren’t any bad teams in October—which is one reason the results are so unpredictable. (Along with the sport’s inherent randomness, which makes it unremarkable for even the very worst teams to beat the best.) But this year, especially, the competitors are evenly matched, as evidenced by the modest differences in actual and expected win totals between the best and worst teams in the playoff field. This season, 12 wins separated the Dodgers and the 86-win Royals and Tigers, while only 11 expected wins distinguished the Dodgers from the Tigers. Those figures are the lowest since 2014 and 2010, respectively, even though the expansion of the playoffs has lowered the bar for entry to October, theoretically enabling bigger gaps between the top and bottom qualifiers for the postseason.

All of those win totals reflect full-season performance, which—thanks to call-ups, trades, injuries, midseason player improvements, and so on—doesn’t always reflect a team’s true talent by the time October rolls around. But even if we focus on clubs’ rosters as currently constituted, the difference from last season is stark. In each of the past two Septembers, FanGraphs’ Dan Szymborski has used ZiPS to project the strength of teams’ rosters as composed on the precipice of the postseason. He ran the numbers two ways: one based on normal player usage, and one based on usage patterns in the postseason, when teams can assign a higher proportion of playing time to their best players (particularly pitchers). Last year, the ranges from the strongest to the weakest postseason teams, according to those two methods, were 134 and 174 points, respectively. This year, they were only 53 and 111. Whether this year’s compressed playoff-team quality is a one-year blip or a sign that owners and front offices are responding to the incentives of the expanded playoffs—which, as I put it in March, “encourage teams to be decent but not dominant”—it’s changed the complexion of the postseason.

Perennial postseason staples such as the Dodgers, Astros, and Braves entered the bracket in more compromised states than they have in previous years. Atlanta (Ronald Acuña Jr., Austin Riley, Spencer Strider, and, at least for the wild-card round, Chris Sale) and Los Angeles (roughly an entire rotation’s worth of starting pitchers) are missing some of their core contributors: Per Baseball Prospectus, the Dodgers led the majors in regular-season days and games lost to injury and trailed only the Braves in projected wins lost to injury. The Dodgers clinched their 11th NL West title in the past 12 seasons with just a few games to go; their 98 wins were their fewest since 2018, and their 96 expected wins were their fewest since 2016. The Braves, who clinched a wild card in the last game played in the regular season, failed to win the NL East for the first time since 2017.

The Astros, who’ve made seven consecutive American League Championship Series, are seemingly the only club that possesses the postseason’s elusive secret sauce. (Insert tired sign-stealing reference here.) But although they won the AL West again, they posted their worst actual or expected record in a full season since 2016, thanks to a slow start that prevented them from surpassing .500 for the first time until June 30. Houston has an entire rotation on the injured list too, but midseason turnarounds by healthy starters Framber Valdez and Hunter Brown, along with the deadline acquisition of Yusei Kikuchi, propelled the Astros’ starting staff to a major-league-leading fWAR after the All-Star break. (Though Valdez was no match for presumptive Cy Young winner Tarik Skubal in Detroit’s Game 1 win on Tuesday.) Among other contenders, the Yankees, Phillies, and Padres appear particularly formidable—the latter two boast the healthiest, most well-rounded rosters at present—but it wouldn’t be shocking for any of them to falter following strong but unspectacular 93-to-95-win showings over the past six months.

Despite the dearth of postseason powerhouses, there’s no shortage of excellent story lines to savor this month. Shohei Ohtani’s first trip to the MLB playoffs, and the possibility, however remote, that he could cap off the first-ever 50-50 campaign, and the first MVP win by a dedicated DH, with a postseason pitching appearance. Appearances from the full phenom lineup of the Jackson Four: Chourio, Holliday, Merrill, and Jobe, all promising rookies ranging in age from 20 to 22. The Yankees’ murderers’ row duo of Aaron Judge and Juan Soto, the most potent twosome this side of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. The shortstop stylings of Bobby Witt Jr., Gunnar Henderson, and Francisco Lindor, all of whom would be MVP candidates if not for the exploits of Judge and Ohtani.

On a team level, there’s the Phillies’ transformation from “nobody believed in us” upstarts to grizzled old hands of October, who have a stronger roster than they did during their deep runs in 2022 and 2023. The Royals’ and Tigers’ improbable paths to the playoffs, featuring Kansas City’s 30-game year-over-year improvement from a 106-loss low, and Detroit’s torrid run to erase a 10-game wild-card deficit on August 10, after the Tigers sold at the deadline. The Padres’ and Brewers’ quests for their franchises’ first championships, in seasons that they started with worse than 50-50 chances to make the playoffs after trading Soto and Corbin Burnes, respectively. The Guardians’ hopes that their historically clutch bullpen will deliver relief from their 76-year title drought. The Yankees’ bid to avoid a 15th straight season without a pennant, which would be their longest such span since the franchise won its first pennant in 1921. (The Guardians won a pennant in 2016, so I’m sure their fans’ hearts go out to the long-suffering Bronx faithful.)

If anything, the wide-open nature of this year’s postseason enhances the suspense: It’s an October unburdened by what has been. So enjoy the small-sample sugar rush, without fearing regret; embrace the chaos, without dreading post-dogpile clarity; revel in the slight upsets without getting upset yourself. (Unless, of course, you’re a fan of the favorite.) Even more so than usual, the World Series is anyone’s to win. And for once, everyone watching knows it.