Rick Mahorn, the former Pistons power forward and center, had Hakeem Olajuwon right where he wanted him. He dipped his shoulder into the Houston Rockets big man, backing him down before gently pulling away for the shot. Olajuwon lost his balance and fell to the ground, but quickly popped up. “You won’t get me with that move again,” Olajuwon said as the two ran downcourt, according to Mahorn.

Now Olajuwon was on offense, pushing Mahorn back, faking one way, spinning the other way, then swishing a buttery fadeaway jumper. Now Mahorn was on the ground. “Sorry,” Olajuwon called out to him. “Did I … shake you?”

Olajuwon started laughing. Mahorn, one of the original “Bad Boys” Pistons, scowled: “The hell outta here with that bullshit!”

Only now, more than three decades later, can Mahorn admit that Olajuwon had gotten him good. “In my mind, you know back then, I was a Bad Boy, I’m like, ‘Mothafucka?! You ain’t shake me! You just made a shot.’” But deep down, he knew it wasn’t any old shot. “It was something new. It wasn’t [Kareem] Abdul-Jabbar’s skyhook. It wasn’t Bob Lanier’s [left- handed hook] shot,” Mahorn says, adding later: “He perfected moves. We call it stealing, but he ain’t steal anybody’s moves.”

Olajuwon was in his second NBA season, and his offensive repertoire wasn’t just coming along—it was developing its own manual. He moved like a guard, shaking left, shaking right, pirouetting this way, that way, falling away for a silky jumper. It was a thing of beauty, the way he made off-balance shots look like layups. If he was fading, especially toward the baseline, the defender knew he was cooked. Olajuwon had such a high arc that he once called the technique “putting [the ball] to the moon.”

“I never saw a shot like he had from that angle,” says longtime sportswriter Jack McCallum. “I mean it looked like he was going to hit the edge of the backboard. The only person I’ve ever seen do that is Larry Bird, and that was in fool-around shooting games. It’s an incredible shot.”

Olajuwon didn’t just move; he flowed. “If he ever got you in what we called the popcorn machine,” says Ralph Sampson, Olajuwon’s teammate on the Rockets, “once you jump up in the air, and you make that move, he knew it, and then he could counter that move into something else. He was deadly with that Dream Shake.”

And then after embarrassing someone, he’d start giggling, like a teenager. Olajuwon played with sheer joy, which came not from racking up video-game statistics but from losing his man completely. Sometimes he’d even miss the shot because he himself was so distracted by the thought that two people could start in the same spot and, in a blink, he could make his defender believe he was going one way, then change directions on a dime to go the other way while his defender lay helpless. “That is art,” he would later say. “It is art to keep someone frozen like that until you are gone.”

Olajuwon turned the court into his own canvas. He was bright red in a black-and-white era. “I am not an artist who paints or draws,” Olajuwon continued. “I look at basketball like an artist looks at painting. When you look at basketball as an artist, you get so much joy from the fakes and the creativity. That is the part that is so much fun.”

“Shake” seemed the only way to describe such a quick move, according to Bill Worrell, the longtime voice of the Rockets, who coined the name “Dream Shake.” He initially called the move on live broadcasts the “shake and bake” or even casually in conversations as doing the “dipsy do.” “I just needed to come up with something that was as regal as he was, that kind of fit his style,” Worrell says. “It’s just that he was such a blur. I always thought of making a milkshake. Just putting stuff in a blender and shaking it up.”

Stuff. That would be the arms and legs and hearts of some of the most elite centers in NBA history, men much bigger and taller than Olajuwon. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Patrick Ewing, and, later, David Robinson and Shaquille O’Neal—Olajuwon shook them all. He had to use his quickness and creativity out of necessity because as strong as he was, he wasn’t going to outmuscle those players. He wore them out by constantly moving. “He was probably one of the first really versatile big men,” O’Neal says. “One of the first big guys to be able to step out.”

And he had this unflappable confidence about him. “Just give me the ball, man!” he’d tell his teammates. “Talk to me, man!” When Dream was hot, Dream was hot. Worrell knew he needed a name for the move that matched that kind of pizzazz and felt he had to run the name by Olajuwon before using it. The two were sitting at a Cleveland airport on a road trip when he asked Olajuwon’s opinion. “That is good,” he remembers Olajuwon saying. “I like that.”

The Dream Shake kept evolving. Take away the middle? He’d spin baseline. Take away the baseline? He’d spin middle, fake once, twice, maybe even a third time, then score. He had a counter for every counter. “You could see the look of desperation on the defender’s face,” Rudy Tomjanovich, a Rockets assistant at the time, says. “That little distance there, 8 to 10 to 12 feet, is, I think, one of the harder shots in basketball, and to do it with big people pushing on you? … It was pretty amazing that he could just keep that soft touch with all that physical play inside.”

Olajuwon approached basketball with the same creativity he did with fashion. Having just one move, in his eyes, was like having one outfit; one wouldn’t wear the same outfit to the party as one would to the gym. He needed to have multiple moves—multiple outfits—revealing his wardrobe slowly while continually adding new pieces.

Players had no choice but to respect him.

Michael Cooper, former Lakers guard: “You got kind of mesmerized in watching him.”

Bill Walton, Hall of Fame center: “His footwork is an extension of his character, his mind, his spirit, his soul, his vision. … He was quick as could be, and quickness is not a physical skill. Quickness is a mental skill. His mind just goes so fast.” (Walton gave an interview for this book before passing away in May 2024 at age 71.)

Vlade Divac, former Lakers center: “If you’re not ready, he’ll kill you.”

Gary Payton, former Sonics guard: “He always tricked you. … He used to give you fits because he was so light on his feet.”

Robert Reid, former Rockets teammate: “It was just like the Swan Lake ballerina.”

Kenny Smith, former Rockets teammate: “He’s one of the few players that was indefensible. Because the shots you were basically saying, ‘Hey, we want to force you to make, take,’ those are actually the shots he was looking for. He was like, ‘Oh, you want me to spin baseline, fake toward the rim, and fade away and shoot? That’s the shot I want to take.’”

Mychal Thompson, former Lakers center and now the team’s radio analyst: “He was a combination of LeBron, Jordan, and Kobe in a center’s body. … He’s gotta change his nickname. He’s no dream. He was a nightmare. … It was exhausting and demoralizing trying to guard him. … I had to really practice—like an opera singer. I had to warm up before the game and start learning how to say, ‘Help!’ in a really loud voice.”

Cedric Maxwell, former Celtics forward and current Boston broadcaster: “He was unreal. … Hakeem was doing the Eurostep before the Eurostep was invented. The spin move on the post was like putting your clothes in a dryer. That spin move, it was like you can’t even watch it, it was so fast.”

That’s because Olajuwon studied guards, ever since that day in Lagos when he saw a teammate dribbling between his legs without looking. That was challenging, and that thrilled him; he didn’t want easy. He felt the traditional back-to-the-basket big-man game was … boring. “I never really liked being a center,” Olajuwon later said. It was far more fun, he realized, grabbing the rebound, dribbling all the way down the court, and creating. Stop and pop. Dunk. Even he never knew what was next.

That thrilled fans—but gave some referees pause.

Ed T. Rush, former longtime NBA veteran referee, remembers studying Olajuwon’s film more closely than he did the film of other players. “The study of his footwork was like none other. I mean, we had not seen a big man put himself in that kind of position on the court and do those kinds of things,” Rush says. “Initially, I think when he first came in the league, we got some of those plays wrong, because it just looked like, ‘Wait a minute. That can’t possibly be legal.’”

Many weren’t sure if Olajuwon was traveling. “If a player is doing something that nobody else can guard,” says Don Vaden, another former veteran NBA referee, “you think, ‘OK, well, he’s got to be doing something illegal.’ … He was just a magician with the ball.” Still, it was challenging to determine with the naked eye which foot was Olajuwon’s pivot foot. “It’s like boom, boom, boom, and he’s gone,” Rush says.

Olajuwon forced referees to prepare a little harder for Rockets games. They’d often watch a series of his moves in their pregame meeting. “We would look just to make sure,” Rush says. “It was pretty amazing.” And, most importantly, “It was not illegal,” says Bob Delaney, another former veteran NBA referee. Referees also realized that they, too, could get caught reveling in his moves. “I do remember a couple times just thinking to myself, ‘I don’t care who it is, there’s no guarding this guy. He’s unguardable,’” says Bill Spooner, another former veteran NBA referee.

Even more impressive, Olajuwon was only 23, a second-year pro just beginning to realize his powers. “He knew he was unstoppable,” Sampson says.

His former teammates and coaches in Lagos weren’t surprised. They had seen traces of the shake and of his quickness, his agility, his fakes, while he played football. When he was running to the ball in football and his defender would chase him from behind, he’d have to shake in one direction in order to evade him, confuse him, and ultimately control the ball and sprint in the other direction. He was not as helpless on the basketball court early on as some portrayed him to be. “He was not the overnight American wonder phenomenon that they want to make the world believe,” says Oritsejolomi J. Isebor, his former Leventis Buffaloes teammate.

Beginning hoops at a later age actually worked in Olajuwon’s favor, allowing other muscle groups to develop first. He was an athlete first, basketball player second, which is why Anthony Falsone, former Rockets head strength and conditioning coach and Olajuwon’s personal fitness trainer, called him “Athlete.” Whereas many have acknowledged how football helped foster Olajuwon’s hand-eye coordination, speed, and change of direction, handball’s influence has been underestimated. Handball is all about mobility, pivoting, faking a defender one way, then shooting over him the other way. Olajuwon constantly reverse pivoted, possessing the spatial awareness and lateral foot speed to know where he and his defender were—and would be—at all times. That ultimately helped him pull off his signature Dream Shake on the basketball court, feeling where his defender was, intuiting which way to spin.

But many didn’t realize that the shake was influenced by something else. Or, more accurately, someone else: Yommy Sangodeyi, his boyhood hero and friend. “Yommy taught him the greatest move Hakeem used in playing in the NBA,” says Agboola Pinheiro, who coached him on the Buffaloes. “I wanted [Hakeem] to be an identical player [to] Sangodeyi, and that was his greatest move in the NBA. That’s the Dream Shake.”

Sangodeyi wouldn’t just shake people; he would rarely miss the shot that followed. Gbade Olatona, Olajuwon’s former Lagos State teammate, says, “Yommy had this clinical touch, wrist touch, after he does the shake, and then faces his opponent. … He has a way of finishing it, you see his wrist dangling like, ‘Heeeeeeey,’ already calling it.” Sangodeyi worked on the shake religiously. “It was almost scientific,” says Delphine Sangodeyi, his wife.

Delphine cautions against giving her late husband full credit for the move. “I think it was not [Yommy] that created it alone. … Yes, it was Yommy, but it was also Hakeem,” she says. “It doesn’t just belong to somebody.” Rather, the move was a blend: “I think the Dream Shake was really the fruit of their friendship,” Delphine says, “and the respect for each other and closeness that they have.”

Like music. One artist shares a song with another; then the listener adds his or her own flavor to it. There were bits of Sangodeyi, and bits of coaches Carroll Dawson and Pete Newell. Bits of football, bits of handball. Inspiration rarely flows back to a single beat.

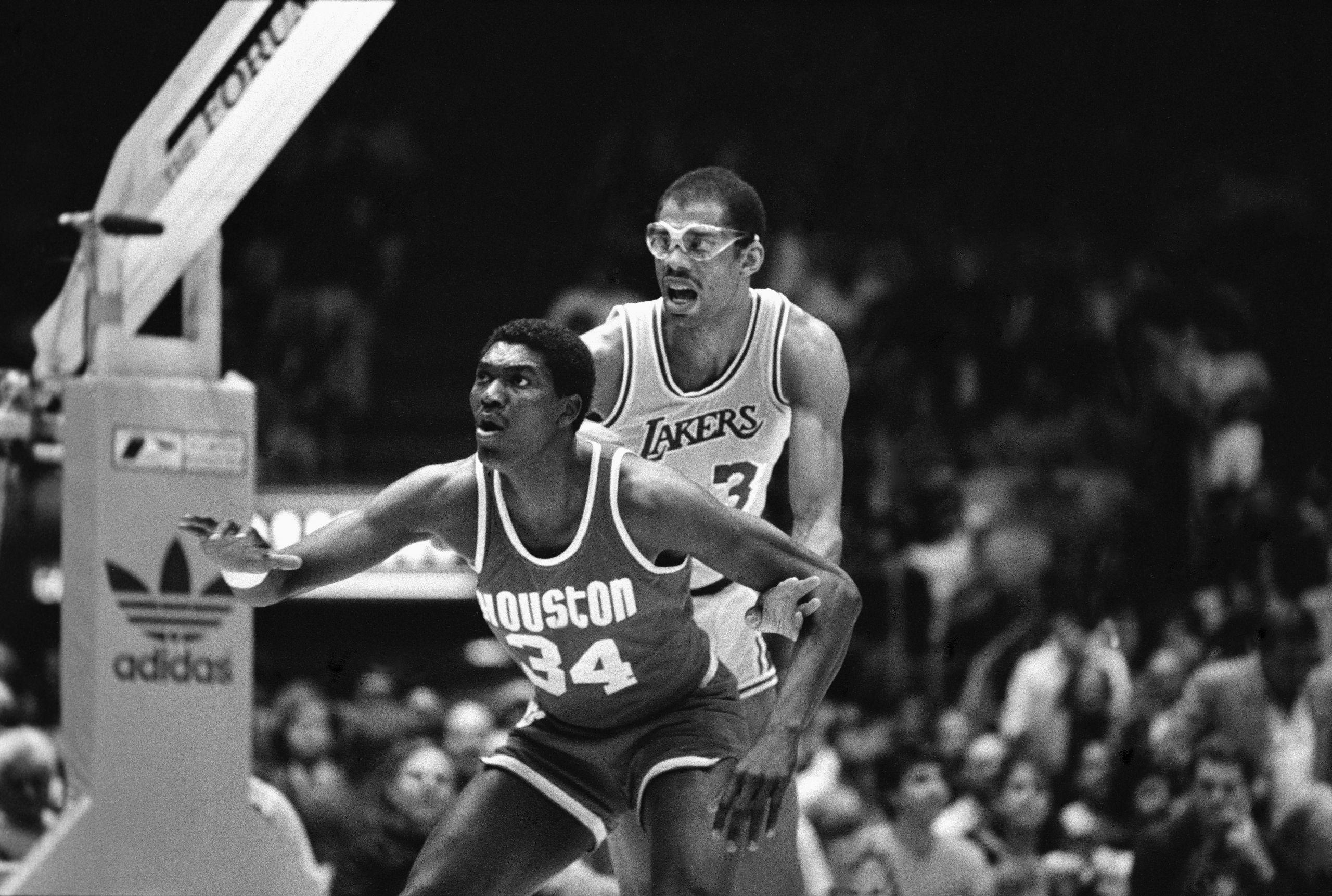

After defeating the Sacramento Kings and Denver Nuggets early in the 1986 playoffs, the Rockets made it to the Western Conference finals against the defending champion Lakers. It was a surreal experience for Olajuwon, taking the court against Magic Johnson and Abdul-Jabbar, the two players he had seen on Ebony covers back in Lagos. The Showtime Lakers, coached by Pat Riley, were the overwhelming favorites. “It was a challenge to [Olajuwon],” says former strength coach Robert Barr. “To be the best, he’s gotta beat the best.”

Abdul-Jabbar had known of Olajuwon’s prowess much earlier, after he had asked Lynden Rose, Olajuwon’s former college teammate who had been drafted by the Lakers in the sixth round in 1982, whether the “big African kid” was legit. “Oh, he’ll be your heir apparent,” Rose said. “He’s that good.”

That much was clear by the end of the series, although one wouldn’t have known it from the Rockets’ 119-107 Game 1 loss. At one point, the crowd of 17,505 rose for a two-minute standing ovation after Johnson dropped a no-look bullet pass to a slashing James Worthy. Riley was so confident he gave his players a day off: “Go to the beach.”

But that confidence, that hubris, backfired as the young and hungry Rockets stole the next three games to take a 3-1 series lead. It was Olajuwon’s coming-out party. He was no longer just one of the Twin Towers—the nickname for the duo of Olajuwon and Sampson—but a gloriously talented player in his own right, exploding for 40 points in Game 3 and 35 in Game 4. To watch 23-year-old Olajuwon against 39-year-old Abdul-Jabbar was to say to yourself, Here is the future. Jerry West, then the Lakers general manager, thought, “This guy is going to get better every year.”

Abdul-Jabbar still took it to Olajuwon, dropping 31 points in Game 1 and 33 in Game 3, but other times, he looked helpless. Sports Illustrated quipped that the Lakers might have had better luck if they had “tried to tie [Olajuwon’s] shoelaces together.” When Abdul-Jabbar showed up to Lakers’ practice with his team down 3-1, he seemed … vulnerable. “I remember at practice, Pat Riley [turned] to Kareem and said, ‘How can we help you?’” says Josh Rosenfeld, the Lakers director of public relations from 1982 to 1989. “I think it was one of the few times in his career that Kareem didn’t have an answer for someone. It was one of the very few times in his career that somebody was better than him. I think he realized that, and it had to be hard.”

Olajuwon had 30 points in Game 5, spinning and scoring at will. The Lakers, knowing Olajuwon had a quick temper, substituted nearly every big man on him to ruffle his feathers, including Mitch Kupchak. In the third quarter, Kupchak kept elbowing and shoving Olajuwon, who finally snapped and punched Kupchak. The two tussled as referee Jess Kersey desperately tried to get between them, finally grabbing Olajuwon by the waist as the big man continued to swing at Kupchak. Olajuwon and Kersey fell to the floor. In the ensuing chaos, someone punched Kersey in the head. “I don’t know which one of you just punched me in the head,” Kersey said, “but if I find out, you’re going to be ejected.”

“Jess,” Bill Fitch, the Rockets coach, said to him, “I know who punched you.”

“Who was it?”

“It was Kareem and Magic.”

Olajuwon and Kupchak were both ejected. “[Olajuwon] was very, very upset that he did that,” says Craig Ehlo, former Rockets guard, “but it also showed that there was a lot of fight in that dog. He didn’t want to go down. … He lost his cool,” Ehlo says, “but you could tell, it kind of sparked us.”

The game came down to the last minute. With the score knotted and just over a second left, Sampson, about 12 feet from the basket with his back to both defender Abdul-Jabbar and the rim, nailed an off-balance prayer of a shot, one that bounced on the front rim, then on the back rim before falling through the net as the buzzer sounded. The Rockets won, 114-112, advancing to the NBA Finals.

“I hate talking about it because we were supposed to kick their ass that game,” says Cooper, the Lakers guard. Sampson was the hero, but Olajuwon had been lethal. It didn’t matter who the Lakers assigned to him; he had his way with them all. “Hakeem was on a mission,” Cooper says. “He literally put that team on his shoulders.” Cooper laughs because now, all these years later, the two are friends. But then? “Enemy for sure.”

“He is truly that wolf in sheep’s clothing,” Cooper says. “Hakeem comes off as nonthreatening, but, shit, ‘I’m going to kick your ass and I’m going to do everything I gotta do.’” Off the court, Cooper says Olajuwon is different. “You think somebody that big and intimidating would have a fierceness about them, but he is so timid and so likable and so courteous. It was a pleasure playing against him. I hated him. But I also had to love him.”

The Rockets faced the Celtics in the Finals. They believed they were on the verge of shocking the world. “We felt we could do it,” Sampson says. The Celtics were loaded with Larry Bird, Danny Ainge, Dennis Johnson, Robert Parish, Kevin McHale, and Bill Walton. “It was the deepest, richest, greatest frontcourt of all time,” says Bob Ryan, the Hall of Fame journalist who covered the team for The Boston Globe. Many consider the 1986 Celtics the NBA’s all-time greatest team. They went 40-1 at home that year. “We were playing so well,” says Ainge, who is now the CEO of the Utah Jazz, “we felt like we were going to beat anybody. But I think we definitely had respect for the Rockets and what they did to the Lakers.”

The Celtics weren’t just confident—they were, in some ways, superstitious. When the Celtics played an early-season game in Indianapolis, Bird and Walton went back to Bird’s childhood home. Walton scooped dirt from where Bird first began playing as a young boy, packing it into a mason jar. He kept that jar in his bag throughout the season, occasionally sprinkling bits of it for inspiration. It was Bird’s team, but no one acted as if he were better than the other. Dan Shaughnessy, longtime sports columnist for the Globe, remembers “how secure they were in their own greatness. There was not a lot of ego.”

Approaching tip-off for Game 1, Olajuwon walked up to Parish and said: “What’s up, big Chief?” That was Parish’s nickname, but it also showed Olajuwon wasn’t intimidated. That was clear as play began, with Olajuwon Dream Shaking Parish early. “Great move, big fella,” Parish remembers saying to him as the two ran down the court.

“He had me allll the way turned around,” Parish recalls.

Parish then remembers catching the ball in the post and outmuscling Olajuwon before softly laying the ball in. “Way to go, Chief,” Olajuwon said. “I guess that’s a little payback, right?” “Yessir! That’s payback!”

The Celtics, though, were too deep and too poised, winning the first two games. Olajuwon had 33 points and 12 rebounds in Game 1, but struggled to find his rhythm in Game 2. He told reporters afterward that he was “ashamed” of himself. He was refreshingly honest. He tended to be hard on himself, hanging onto mistakes.

Olajuwon came back with a vengeance to help the Rockets win Game 3, but the Celtics stole Game 4 in Houston to hold a commanding 3-1 series lead. Olajuwon wasn’t going to give up. “The tougher the game got,” Ainge says, “the tougher he was. And I always respected that about him.”

The Celtics’ front line felt it. “Just the hardest elbow I ever received,” Walton said. “He was a rock. My whole body just went numb.” But what stood out about Olajuwon more than anything was his mentality. “He was the only person on the Rockets not scared shitless,” says Jack McCallum.

Olajuwon led the Rockets to a 111-96 Game 5 victory, tying a then-Finals record with eight blocks, but the game ended in a brawl as Sampson and Jerry Sichting got into a fight. Celtics players were pissed. Up 3-2, the Celtics headed back to Boston and were ready to end the series. “I’ve never seen a team more focused in my life than when we lost that game,” Ainge says. “As we sat and listened to the celebration in Houston, there was a lot of frustration and anger in our locker room.” Nobody said a word on the plane ride home. Practice the next day was so intense that Celtics coach K.C. Jones ended the session early. He didn’t want anyone to get hurt, and he knew the team was ready. “There was no way we were losing Game 6,” Ainge says.

Tensions were high at the Garden. Bird was so fired up he could feel his heart pounding through his chest, a feeling that lasted until the final buzzer when he thought he might have a heart attack.

Rockets players just tried to focus on their play. But Boston was so in sync that, at halftime, Bird changed his uniform, something he never did; he felt so confident of victory that he wanted to have two championship uniforms. Indeed, the Celtics ended up winning the title with a 114-97 rout.

As disappointing as the loss was, Rockets players were filled with hope. They felt as if they were merely scratching the surface of a bright future in which they’d compete for many championships. But that isn’t how history played out. It would be a painful road ahead, one that Houston couldn’t quite figure out how to overcome.

Excerpted from Dream: The Life and Legacy of Hakeem Olajuwon by Mirin Fader. Copyright © 2024 by Mirin Fader. Reprinted by permission of Hachette Books an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc., New York, NY. All rights reserved.