The great directors tend to have their great muses: Scorsese has the mob, Leone had the American West, De Palma has Hitchcock. For Sean Baker, his greatest artistic muse is the world’s oldest profession. Or, perhaps more accurately: sex work in all its many forms.

This isn’t an entirely new observation, nor is it meant to be reductive. Baker’s work—which includes Tangerine, The Florida Project, and Red Rocket—is dripping with empathy for its characters. His filmography is on the short list of the best of the past decade, and that’s largely thanks to his ability to plumb new depths each time out. “I became friends with [sex workers] and realized there were a million stories from that world,” Baker said earlier this year, before teasing that his next movie would also include sex work. “If there is one intention with all of these films, I would say it’s by telling human stories, by telling stories that are hopefully universal.”

Baker’s latest is his most accessible, and it may be his best yet. Anora, which opened in limited release last week, stars Mikey Madison as a sex worker who has a torrid love affair with the son of a Russian billionaire. It won the top prize at Cannes this spring and seems like a lock for a Best Picture nomination (at the very least). It also puts Baker on another short list—one of directors who are making major works that prominently feature sex. In two watches, I clocked eight distinct sex scenes. (Or, as Baker calls them, “sex shots.”)

Movies have come a long way since the dawn of New Hollywood five decades ago, when the X-rated Midnight Cowboy became a box office hit and won Best Picture. While movies like Anora and last year’s Poor Things feel like anomalies, bigger-budget crowd-pleasers like Basic Instinct and Fatal Attraction are now essentially nonexistent. Even some recent hits hailed by critics as sexy, like Challengers and Twisters, have been devoid of much on-screen action. (And in the case of Twisters, the movie couldn’t deliver even a single kiss thanks to a note from Steven Spielberg, who himself has never had much use for sex in his films.)

Sex scenes aren’t entirely absent from the current theatrical landscape: The megahit and last year’s Best Picture winner Oppenheimer had a few, and even Joker: Folie à Deux had a brief moment of coitus—whether you wanted it or not. But it’s become hard to shake the feeling that these instances are increasingly rare. So what gives? Is cinema actually in a dry spell? Or is it all just a fantasy?

Well, allow The Ringer to present to you the naked truth. We’ve crunched the numbers since the turn of the century, and by at least one metric, sex in movies is way down.

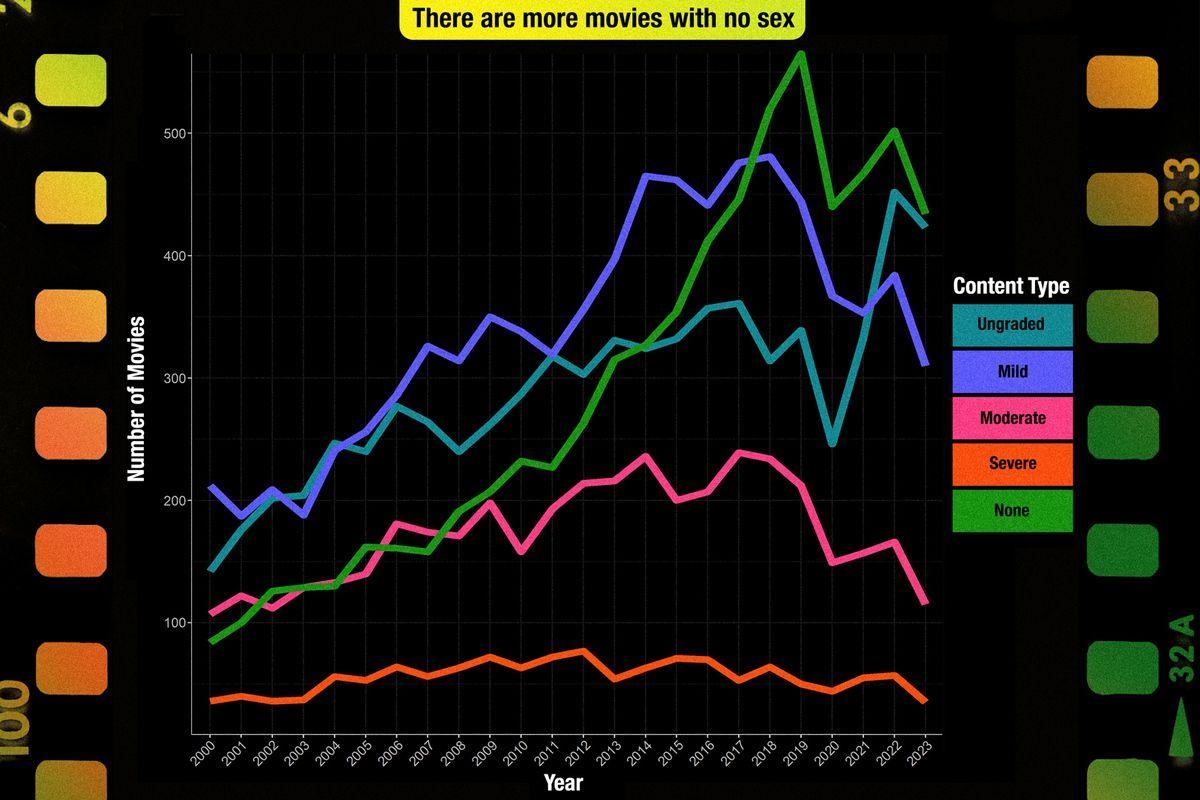

To determine the amount of sex in movies over time, we pulled data from the IMDb Parents Guide, which allows users to self-report the content they come across in films, including drug use, violence and gore, profanity, and—most importantly for our purposes—sex and nudity. That’s a data set of more than 40,000 films from the dawn of the millennium through 2023. The chart above shows that not only have the numbers of movies tagged as having “mild” and “severe” sexual content declined by as much as 30-50 percent from their peaks but the number of movies tagged as having no sexual content has skyrocketed from less than 100 movies in 2000 to 400-500 in the past few years. (There’s also been a spike in movies that have yet to be graded for a few reasons: First, people can’t grade a movie until it has come out; second, there’s typically some lag time before enough people leave grades for IMDb to report the data.)

Some of this is to be expected, as R-rated movies have been in decline for years now. (For reference: According to data from the box office tracking website The Numbers, a quarter century ago in 1999, 245 R-rated movies were released. They had a nearly 41 percent market share. Since 2021, the number of R-rated releases has ranged from 113 to 144, and they haven’t posted a market share greater than 30 percent in that time frame.)

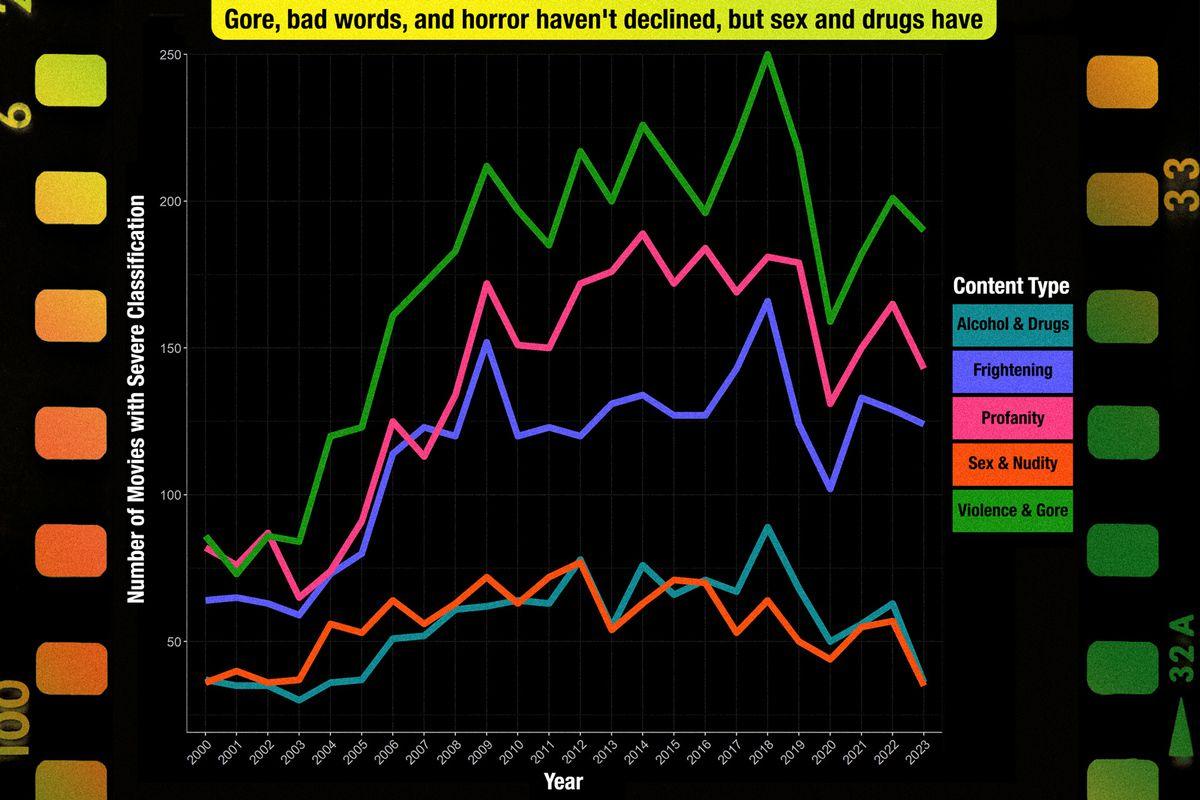

Fewer R-rated movies should naturally mean fewer movies tagged on the Parents Guide as having steamy content. But there’s a catch: There hasn’t been a corresponding drop-off in the other areas that users self-report.

While the numbers for movies tagged as having “severe” violence and gore, frightening content, or profane content are still below their peaks or near peaks in 2018, those figures have bounced back since 2020. (For obvious reasons, 2020 saw a decline in new movies released overall.) Meanwhile, the number of movies that users reported as having “severe” sex and nudity remains down—below its circa-2000 numbers. Only 35 movies in 2023 carried that tag, compared with 64 in 2018 and 77 in 2012. (Interestingly, alcohol and drug use in movies also appears to be way down, though still above the early-century numbers. Perhaps we’ll tackle why for the Trainspotting anniversary in 2026.)

With an average of about 1,900 movies added to the database every year, we’ll likely never get complete numbers on just how chaste or unchaste movies have become. But what we can review points to a clear statistical trend that backs up the anecdotal evidence: Movies today are far more sexless than they have been in the past.

But don’t mistake this shift toward prudishness as a newfound box office puritanical streak. It is, like most things in Tinseltown, the result of trying to cater to tastes, market factors, and changes in consumption habits. The adage has long been that sex sells, but now it appears the opposite is true—at least at the Cineplex. The explanations paint a picture of an industry that has rarely put morals above profits yet suddenly wants to keep its clothes on.

It’s worth remembering that even three decades ago, the top of the box office wasn’t a Caligula-style orgy of flesh and debauchery. While you’ll see the occasional Basic Instinct or Indecent Proposal crack the top 10 in the early ’90s, the highest-grossing films were often the big-ticket action, IP adaptations, and children’s movies that we still expect to make bank today.

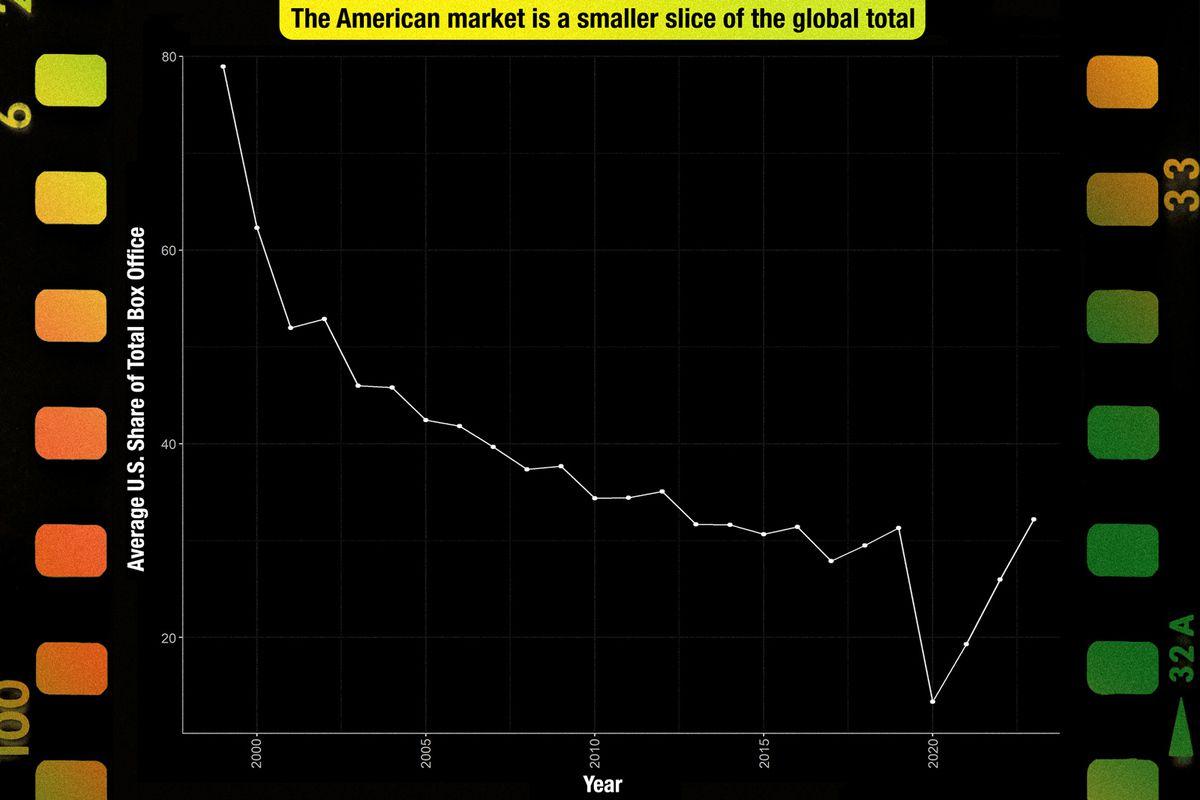

What has changed is the ability to make a Basic Instinct or Indecent Proposal, particularly at that scale. “You can look at it and see it as the box office and as the business has been narrowing, especially theatrically, in the last couple of years,” says Joshua Lynn, president of box office forecasting company Piedmont Media Research. The reason for this is the same reason driving many of the decisions at the top of the Hollywood landscape: the importance of foreign markets to the bottom line.

It’s a matter of simple economics. While a Gower Street Analytics report said that North America remained the largest moviegoing market in the world in 2023 with $9.07 billion in sales, China was estimated to be second at $7.71 billion. Gower Street didn’t report numbers for India, but a separate study put the country’s box office haul roughly in line with third-place Japan at just shy of $1.5 billion last year—but with much more room for growth.

With those countries’ receipts at those levels, the American audience is taking up an ever-shrinking piece of the pie. Here’s the percent of revenue for the top 200 of each year that’s come from U.S. ticket sales, dating back to 2000.

In 2023, just north of 30 percent of ticket-sale revenue came from the U.S. That’s up from the COVID-era nadir but dramatically down from the early 2000s, with the percentage at nearly 80 percent at the turn of the century before dropping to about 60 and 50 percent in the years immediately following. It’s affecting all types of non-blockbuster films: not just your Basic Instincts and Indecent Proposals, but also your Old Schools and Superbads. “Not just specifically ‘adult’ films, but even comedies—you’re seeing less of those being made now, theatrically, because those don’t travel as well,” Lynn says. “Comedy doesn’t travel as well to other countries. A lot of it is very sort of specific, where you’ve got action movies or sci-fi: That travels a lot easier to different countries, to different cultures.”

Of course, this applies to movies at the highest end of Hollywood—Anora won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in May and is currently one of the betting favorites for Best Picture, but it’s distributed by Neon and has different goals than, say, Bad Boys: Ride or Die. But in the place of more adult dramas and other suddenly more niche films, the larger studios are investing more in reliable, preexisting IP—Hollywood’s North Star in recent years—and horror movies, which tend to be relatively cheap to make. When it comes to filling out the slate beyond the biggest-ticket releases, Lynn says, the studios look to mid-budget action movies helmed by the likes of Jason Statham or Gerard Butler. And it’s paid off: Statham’s 2024 movie The Beekeeper and Butler’s aptly titled 2023 Plane both grossed more internationally than they did in the U.S. “The reason those work and the reason those are made, for the most part, it’s not because of how well they necessarily do in America, but because they’re able to presell them foreign for a pretty set amount,” Lynn says. “There’s books that people will go by—‘OK, here’s an action movie starring this person. This is what we expect it to make in this country, and so this is what we can sell it for.’”

Besides trying to predict what kinds of films will land with international crowds, there’s a scarcity issue, says Lynn. Every movie must be reviewed by the Communist Party of China before it’s granted release in the country. According to a Deadline report last year, only 15 U.S. movies were allowed into China in 2022. That was down from 2019, when more than 30 U.S. movies were released there. Part of this is due to a desire to promote Chinese productions rather than American. But some films are denied for political reasons—take 2022’s Top Gun: Maverick, which was snubbed by the CCP for its inclusion of the Taiwanese flag—while others may get flagged for having sexual content. “China and India—the cultures or the governments might be more restrictive, and so you’re not going to see things that are as sexually driven,” Lynn says. Even when China agrees to let a movie into its domestic market, it may edit out material deemed too steamy for its audience, like when significant cuts were made to The Shape of Water.

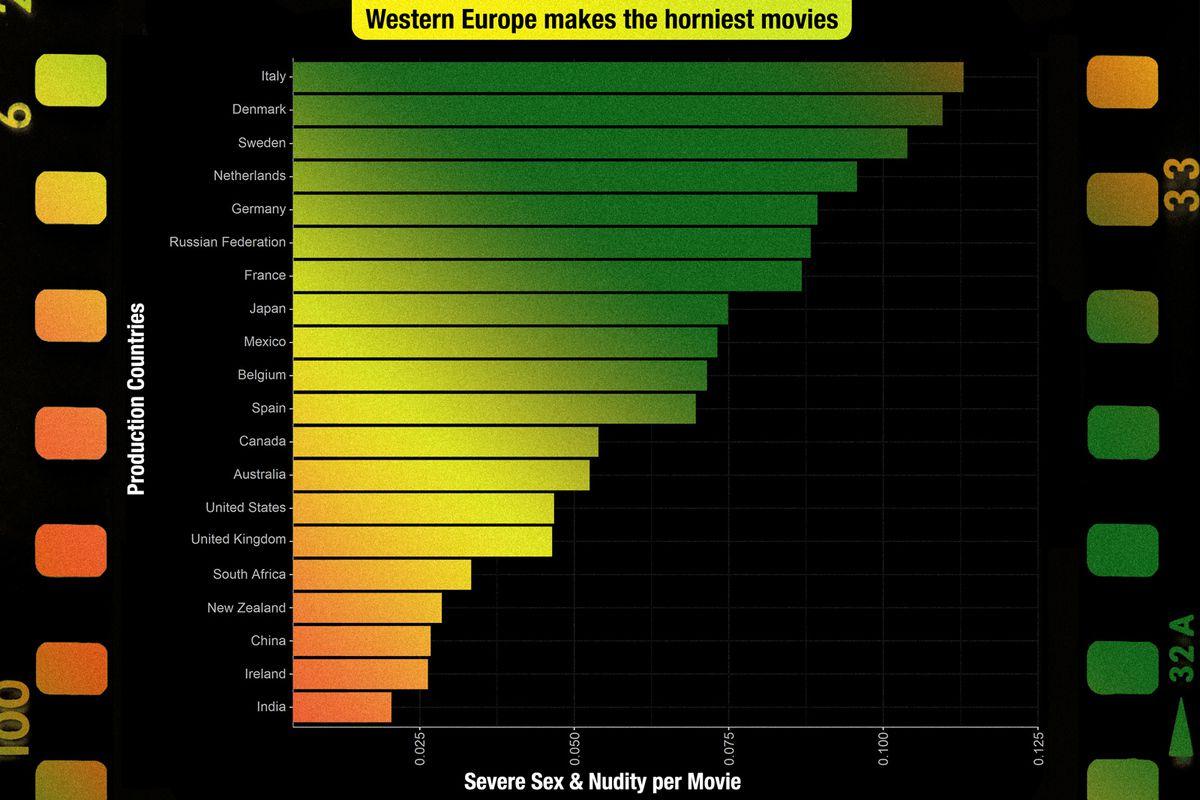

Indeed, returning to the IMDb Parents Guide, you can see just how relatively little “severe” sexual content is appearing in not just American productions but also Chinese and Indian ones.

The first takeaway: As always, Italians do it better, with the highest rate of movies released from 2000 to 2024 that were tagged as having “severe” sex and nudity (11 percent). But Europe takes the first seven spots, with the U.S. coming in at no. 14 (5 percent). China and India rank no. 18 and 20, respectively, at about half of the U.S. quotient, with only Ireland in between them—though, by some estimates, Ireland produces as few as 20 domestic films a year, while India sees as many as 2,000 and China made around 800 in 2023. When you factor in North American releases—about 500 in 2023—that’s a lot of skinless cinema coming from the largest movie-making markets in the world. It’s also a potential indication of less consumer interest from two of the largest (and still growing) movie-buying markets in the world.

To A/B test how this shift has played out specifically at American studios over the past few decades, it’s helpful to look at RoboCop of all things. The original 1987 film was directed by Paul Verhoeven and rated X before it was trimmed to appease the MPAA, which reviews most big-ticket movies before their theatrical releases. The R-rated version grossed $53 million domestically on a $13 million budget. José Padilha’s 2014 remake was rated PG-13. It grossed just $59 million—which, when adjusting for inflation and accounting for its $100 million–plus budget, means the movie was far less successful in the U.S. than its predecessor. However, the reboot made $184 million internationally—good for 75 percent of its gross revenue. (It should be noted we can’t compare the two films’ international hauls because it’s difficult to track down international box office numbers prior to the 1990s.)

For Rich Juzwiak—a culture writer who’s written for places like Jezebel and The New York Times and currently writes many things for Slate, including the sex and relationship column How to Do It—the differences between the two films underline the direction the movie industry has been heading for decades. “PG-13 became the norm,” he says. “It just seemed like as our culture turned more and more toward the importance of numbers, movies did as well. That’s not to say that numbers weren’t always important, but there seemed to come even more fear, even more adherence to, ‘This has got to hit. We have to make this as across-the-board appealing as possible.’ So you do that by defanging it.” (Another egregious example Juzwiak brings up relates to, again, the Top Gun franchise. 2022’s Top Gun: Maverick has a brief romance scene with only implied sex. The 1986 original fully goes for it, with a moonlit encounter soundtracked by Berlin’s “Take My Breath Away.” Maybe slow down on that need for speed.)

As for the moment that may have soured Hollywood’s feelings about sex and erotic thrillers, Juzwiak points to another Paul Verhoeven movie: Showgirls. The 1995 film is notorious for a few things: its NC-17 rating, its failure at the box office, and its imaginative approach to pool sex. Today, the movie has been reclaimed (rightfully) as a cult classic, but its performance at the time—coupled with the failure of William Friedkin’s erotic thriller Jade the same year—caused Hollywood to rethink where it was investing its resources. “I don’t think that this is a nefarious plot on Hollywood’s part to take sex out of our culture,” Juzwiak says. “I think it’s just about making money.”

So sex in movies is down. But that doesn’t necessarily mean we’re less into sex as a culture. Lynn points out that Pornhub is the 20th-most visited website in the world, by one metric, and every person interviewed for this article cited ease of access to pornography in the 21st century as one reason why sexual content in movies is down. “Back in the day, when you couldn’t just bring up whatever porn you wanted to see with a few keystrokes, I think more people were relying on [mainstream movies] for titillation,” Juzwiak says. “Obviously, not masturbating in the theaters—which, Basic Instinct, a lot of people went to the theaters to see that movie. But just in general, to have any sexuality in front of your eyes, doing anything to your senses, there was a certain reliance on these movies that just became kind of irrelevant as time went on into the 2000s.”

It’d be unfair to make a one-to-one comparison between movies and porn. Despite the outsize reputation of Basic Instinct’s most infamous scene, it was a small piece of the larger film, and (presumably) many people got something out of it that had nothing to do with titillation. We can debate the artistic merits of porn all day, but what’s undeniable is that in most cases, people seek it out primarily for arousal. Still, the fact that many of us are seeking lewd and sexual content in this way shouldn’t be shocking. It should be considered natural.

This idea that lewd and sexual content is better suited to be consumed in the privacy of our own homes, on smaller screens, may help answer where this type of content has gone: television. The streaming age gave rise to peak TV, which happened practically in tandem with the decline of the “adult” dramas on the big screen. We’ve reached a point where Presumed Innocent gets a star-studded reboot on TV and Alfonso Cuarón is making a seven-part miniseries starring Cate Blanchett. It’s easy to envision both as mid-budget, profit-turning movies 30 years ago. But instead, they landed on Apple TV+, and yes, both feature sex and nudity. (In the case of Presumed Innocent, the IMDb Parents Guide has it pegged as “moderate.” For Cuarón’s Disclaimer, the early episodes are firmly in the bright-red “severe” category.)

It’s tough to gauge just how commonplace sex has become on streaming, but it stands to reason that it has increased. We were unable to find any recent reliable studies showing just how much it’s jumped in the past 25 years, but that was certainly the trend in the mid-2000s, as HBO and Showtime redefined the concept of television, both in terms of storytelling and what was permitted to be shown. (A study from 2022 by VidAngel—a video-streaming service that allows users to filter out nudity, sex, and violence and therefore has a vested interest in these numbers—found that on-screen sex was up dramatically in the streaming era, but it didn’t separate TV and movies.)

There are likely myriad reasons why TV sex has increased while movie sex has dwindled. For one, Juzwiak says that streamers don’t have the MPAA breathing down their necks and threatening an R rating—or, even worse, an NC-17 rating. Also: Because TV shows aren’t reliant on the foreign box office, they don’t have the same distribution issues that movies may. Or maybe it’s partly a matter of available real estate: One or two sex scenes per episode of a 10-hour show feels like a lot less sex than three sex scenes in a two-hour movie, Juzwiak says.

“Even though Game of Thrones is about politics and dragons, it’s also about sex, or at least it’s one of the things that would come immediately to mind when they think about that show,” he says. “So I think for whatever reason, TV is able to just kind of jump that hurdle better.”

It might also be a matter of age for the target demo. A 2022 survey showed that 18 percent of people in the U.S. aged 45-64 reported never going to the movies. That number shot up to 30 percent for people aged 65 and up. By comparison, only 15 percent of people aged 35-44 said they never went to the cinema, while the number dropped to 9 percent for young adults aged 18-34. In terms of the frequency with which people go to the movies, a similar trend emerges: 12 percent of people aged 18-34 reported going to the movies often, and the numbers dropped with each successive group. Just 4 percent of people aged 65 and up said they went to the movies frequently. Meanwhile, a 2022 Wall Street Journal report found that viewers aged 50 and older have become the largest streaming demographic, making up 39 percent of the audience on Netflix, Hulu, and Disney+ at the time of the study.

The factors driving older viewers away from theaters and to their TV sets are up for debate—lack of appealing options at the Cineplex, perhaps, or maybe at a certain point, life’s responsibilities make going to the cinema a hurdle not worth jumping. But if older people aren’t making as many trips to the theater, it makes sense that streamers would be serving them more “adult” fare on the small screen. And if younger audiences are making the pilgrimage, it’s better to try to meet them on their terms. “I just think the bottom line is that people want to go to the movies to have fun, and the age bracket of people who want to go to the movies is younger,” says Gigi Engle, a certified sex and relationship psychotherapist and resident intimacy expert at 3Fun. “So maybe they veer away from sex.”

But maybe the reason these younger people are veering away from sex has only a little to do with the concept in general and more to do with how it’s often depicted. And it may point to the direction sex on the silver screen could be headed.

There’s no shortage of headlines that could make you believe that Gen Z is, well, a little more puritan than previous generations. They drink less. They have fewer social connections. And the big one: They’re not having as much sex.

There are valid explanations for this in Engle’s view that don’t necessarily equal younger people being boring. They had COVID-19 to contend with, they’ve had much easier access to porn than previous generations, and they came of age in the smartphone era. Those three factors alone are enough to alter their approach to interpersonal connections. “They’re much more involved in their devices; they’re less likely to meet up in person,” Engle says. “I don’t know so much that it’s a noninterest in sex as much as it’s a socialization thing because everybody’s just on their phones and not really meeting up in person as much.”

The changing socialization of Gen Z also shapes what they want to see in movies. Yalda T. Uhls is the founder and executive director of the UCLA Center for Scholars and Storytellers, which last year released the first version of “Romance or nomance?,” a study that found that younger people had a different relationship with on-screen sex than previous generations. The top-line items from it: 51.5 percent of people aged 13-24 wanted to see more platonic relationships in their movies and TV shows, while 47.5 percent thought that sexual content was not necessary for advancing the plot. In this year’s version of the study released this week, those numbers jumped to 63.5 percent and 62.4 percent, respectively.

The easy takeaway is that young people are turned off by sex—or at least sexual content. But it’s more nuanced than that, Uhls says. It’s not that they don’t want to see zero sex, it’s that they want to see themselves reflected in what they’re watching—at that age, forming friendships is very often more important than sex or romance—and when do they do want sexual content, they want it to feel authentic to the stories and characters. “They don’t want to see it shoehorned in,” Uhls says. “It’s intrinsic to the characters, and it’s intrinsic to the storytelling. Anora—it would be weird not to have it. If it feels really authentic and real, then they want to see it.”

In other words: the opposite of what movies like Basic Instinct offered—those highly stylized moments, almost necessitated by the shape of the movie. “When you watch Basic Instinct or any of the copies of it—Body of Evidence, whatever—the sex scenes play,” Juzwiak says. “There’s a certain inevitability to them, there’s a certain amount of, ‘And here’s what we’re doing now.’ The plot stops. It’s kind of a musical number, almost. Or the way musical numbers happen.”

Uhls, who was an MGM studio executive in the 1990s, stressed that Hollywood could stand to listen to younger people on this issue. But the people making the movies may be in the process of shifting toward more considered (if not more realistic) sex scenes regardless. The past few decades have seen the growth of queer sex in media, meaning better representation for different groups of people. But the continued impact of the #MeToo movement also plays a role. That may have had an effect on the amount of sex we see in movies—Piedmont Media’s Lynn says that it led to an environment where female actors are more willing to say no to situations that make them uncomfortable and where men in power are more likely to listen to their concerns. It also gave rise to something else: intimacy coordinators.

The coordinators are a relatively new presence on Hollywood sets, and at a base level, they’re there to look after actors’ comfort, well-being, and safety. But they’re also there to help choreograph and execute the sex scenes. “It’s a much better experience for the actors, but it’s also a better experience for the viewer because those sex scenes are much more highly coordinated,” Engle, the sex therapist, says. “The actors are kind of thinking about exactly how their characters would have sex, and I think that makes for better sex scenes in general on-screen.” More realistic scenes featuring more comfortable actors may mean fewer gratuitous shots for the camera.

And in the end, if the overall number of sex scenes is declining, that may be the means to an end we’re looking for: a better approach to sex on-screen. For now, we’ll take it where we can get it, like in the sexually-charged-if-not-entirely-a-sex-scene Challengers threesome scene (or in the maybe even more sexually charged tennis scenes). Or, as Juzwiak calls out, the armpit scene in Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, which used implied foreplay and sharp editing to create something that felt even more sexual than if the film had just shown the two leads actually having sex. “Céline said that she liked doing that because it was better than a simulated sex scene, because that act that she showed was real, and that was intimacy,” Juzwiak says. “She was able to kind of be explicit without actually even suggesting sex at that point. So that, I thought, was really creative and kind of novel. And as long as there are filmmakers that are looking for ways to convey that kind of intimacy and connectedness without actually doing a kind of rote sex scene, I’m all for that.”

Which brings us back to Anora, where the so-called “sex shots” feel anything but rote. Of course, Sean Baker’s film is free from the international pressures that face studio blockbusters. But Anora’s many instances of sex serve a variety of purposes. They’re sometimes casual, sometimes emotionally devastating, but always natural feeling. They’re intrinsic to the plot, often bold artistic choices, and sometimes just downright fun.

But even if they weren’t, would that be such a bad thing?

“Of course there’s gratuitous stuff, but sometimes gratuitous stuff is amazing and fun, you know?” Juzwiak says. “Are the sex scenes in Showgirls necessary? No. Would I be absolutely heartbroken if I couldn’t watch Elizabeth Berkley thrashing around a pool tomorrow because some kid on Twitter complained about it? Yes, that would break my heart.”