It’s traditional, before a World Series starts, to compare and contrast teams, breaking down the rosters piece by piece and pronouncing who has the edge. We could run through that exercise with this season’s pennant winners, in advance of Friday’s Game 1, but it wouldn’t be very revealing. The Dodgers are much more capable base runners, excel at controlling the running game, and have the better bullpen, probably. (Who really knows about bullpens?) The Yankees boast a stronger starting staff and superior pitch framing and blocking, and their righty-killing bats may match up well with the Dodgers’ lefty-less rotation. The lineups (relentless) and defenses (fine)? Too close to call. There’s not a lot of daylight between the best teams in their respective leagues; even the projections refuse to take sides, stubbornly sitting on the 50-50 fence.

Maybe the mistake is studying the players who are on the roster, rather than those who aren’t. In this case, the players who may make the difference don’t show up on the depth chart—unless the depth chart lists the injured pitchers and hitters who’ll be forced to sit out the series. As the Fall Classic starts, the Yankees have health on their side. The Dodgers don’t. L.A.’s lopsided list of injury-compromised players won’t necessarily decide the series—the club beat the Padres and Mets while suffering from most of the same aches, pains, and surgical scars—but it is a hurdle that hasn’t been placed in their opponent’s path.

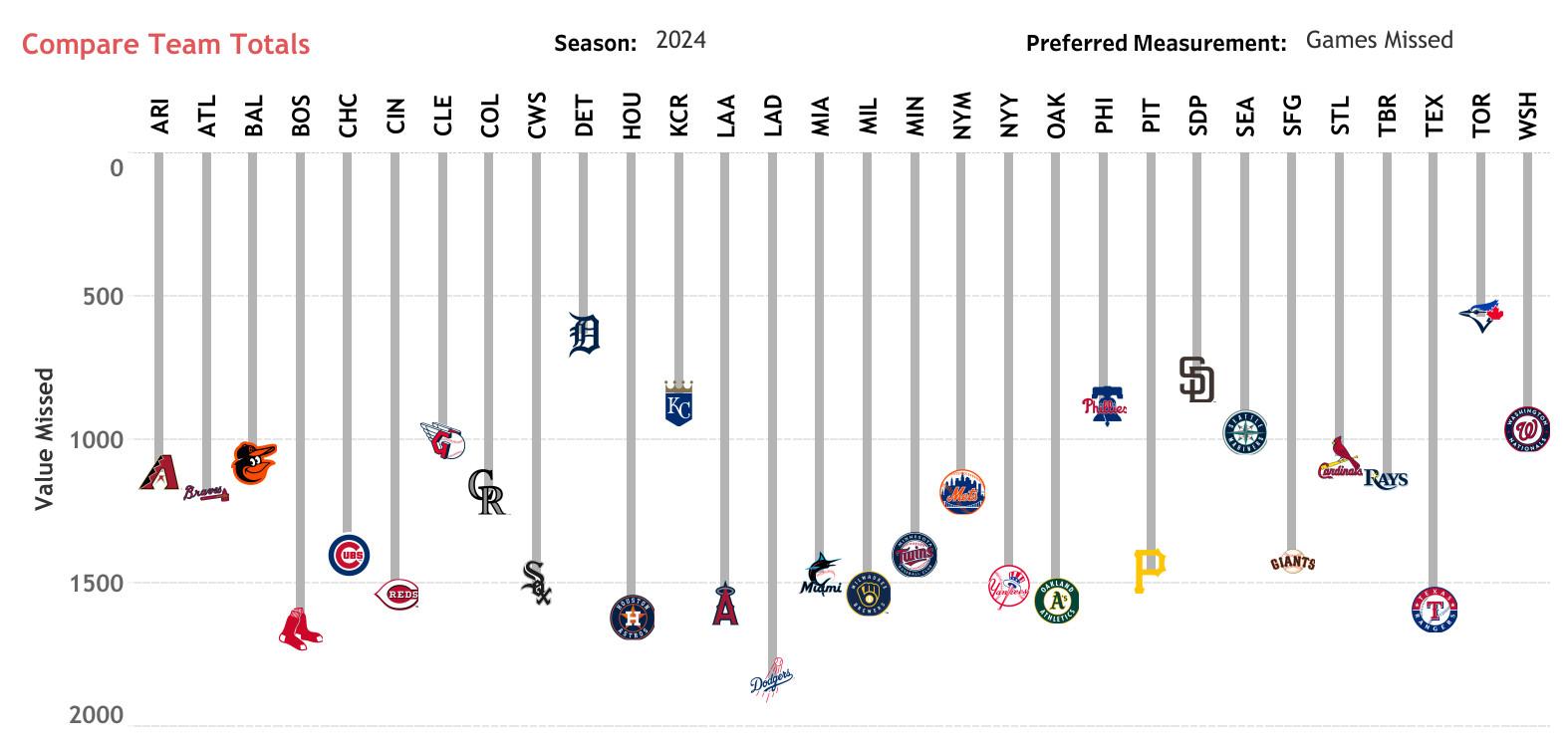

Last year, the Yankees lost by far the most projected wins to injury of any team, according to Baseball Prospectus’s Injured List Ledger. This year, they lost fewer than average. That’s far from the only factor that propelled them from a disgraceful-by-pinstriped-standards 82 wins in 2023 to 94 wins and an AL East title in 2024—have you heard of Juan Soto?—but it sure as heck helped.

The Dodgers, meanwhile, went from losing the second-most projected wins to … losing the second-most projected wins again. L.A. led the majors in player games missed on IL stints.

In January, FanGraphs’ Dan Szymborski pointed out the downside of the Dodgers’ pitching approach:

There’s certainly some risk with the Dodgers. They have a lot of talented arms, but they have very little certainty in terms of who will be available, when, and for how long. If they manage to get five of Yamamoto, Glasnow, Bobby Miller, Walker Buehler, Gavin Stone, and Emmet Sheehan all in the rotation at the same time, this is a very dangerous unit. The Dodgers have been happy to assemble rotations on the fly, but while that has worked out in recent years, it’s no guarantee going forward.

That’s a prescient passage. When pitchers and catchers reported, the Dodgers boasted baseball’s best projected rotation. Sure, many of their pitchers had been hurt before—one of them was named Kyle Hurt, which was a little on the nose—but their list of starters projected to produce positive WAR went about a dozen deep. If a few fell, there was no shortage of next men up.

At least, until there was. Tyler Glasnow. Dustin May. Tony Gonsolin. Clayton Kershaw. Gavin Stone. River Ryan. Emmet Sheehan. And yes, Kyle Hurt. One by one, they all injured (or failed to recover from previously injured) shoulders or elbows … not to mention a toe, and even an esophagus. (Even after coming back from shoulder inflammation, Miller unexpectedly flamed out and got demoted to the minors, and midseason call-up Justin Wrobleski got knocked around and became another next man down.) The Dodgers traded for Jack Flaherty at the deadline, and they still finished 20th in starting pitcher WAR during the regular season. More importantly, that entire phantom rotation—most of two rotations—has been off-limits to L.A. this month.

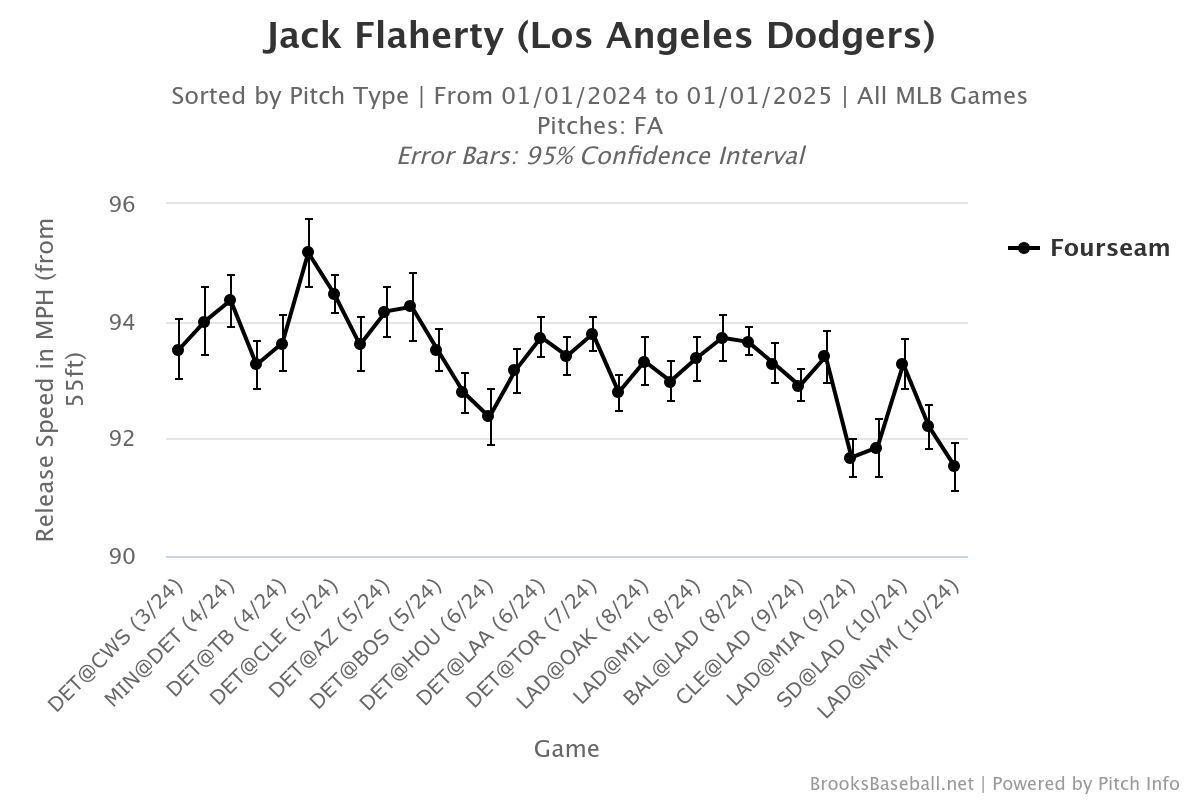

The Dodgers are down to three starters, and each of them comes with a cause for concern. Flaherty, who’s starting Game 1, saw his pitch speeds sink in September, and his strikeout and walk rates soon headed in similarly disconcerting directions. The righty’s one strong start this postseason, in NLCS Game 1, was sandwiched between a couple of clunkers. This week, Dodgers pitching coach Mark Prior said Flaherty’s problems aren’t injury related, but Prior still described himself as “moderately concerned.”

And that’s the guy going in Game 1. Then there’s Yoshinobu Yamamoto, who’s averaged four innings per start (and maxed out at five) in seven outings since his mid-September return from a strained rotator cuff that cost him almost three months. Yamamoto’s bat-missing ability has come and gone—he induced five and four swings-and-misses, respectively, in his two NLDS starts before whiffing 16 in NLCS Game 4—and he requires extra time between starts. Finally, there’s Walker Buehler, who hasn’t been his old self in his first season post–Tommy John surgery. Of the 145 pitchers who made as many starts this season, Buehler’s 5.54 FIP was fifth worst. His first start this postseason was so shaky that his four scoreless innings in NLC Game 3 were seen as something of a triumph.

The Dodgers’ pitcher-injury issues are nothing new. The table below, based on data provided by BP’s Derek Rhoads, shows the team’s annual MLB ranks in non-COVID pitcher IL stints, dating back to 2018 and excluding 2020.

The Dodgers’ Perennial Pitcher-Injury Issues

That pattern is partly a product of L.A.’s willingness to flex its financial might by taking risks on injury-prone pitchers in the draft and free agency. The Dodgers could afford to splurge on, say, Glasnow, knowing that although he might miss time throughout the year, the deal would be worth it if he could answer the October bell. That gamble didn’t pay off fully this year, but Glasnow did throw a career-high 134 innings, which helped L.A. fend off the Padres in the NL West.

However, the problem is persistent and widespread enough that it may be a product of how the Dodgers develop pitching. Pitcher injuries are a scourge on other teams too, and it would seem to make sense that if modern, max-effort pitching has helped cause an increase, then the teams at the bleeding edge (so to speak) of developmental trends would be hardest hit. (Dodgers president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman’s former team, the Rays, ranks second in pitcher IL stints, days missed, and games missed since 2018; the Yankees rank fourth in the latter two categories.) Last month, Friedman pledged to reevaluate the team’s approach to pitching development, but that won’t summon more reinforcements now. No wonder Dave Roberts keeps getting asked about using Shohei Ohtani in relief; the bullpen games will continue until pitcher health improves.

With an all-righty rotation, the Dodgers will be at the Yankees’ mercy in the early innings: During the regular season, New York’s lineup was the 10th best against southpaws but the best against righties. If playoff performance to date is any guide, though, the Bombers’ bats won’t see those starters for long. What with all three righties’ inconsistency, Yamamoto’s rest schedule, and the lack of a palatable fourth starter, Roberts has let the Dodgers’ Bullpen Dawgs out early and often. Dodgers relievers have thrown 58.8 percent of the team’s innings this month, a rate barely lower than those of the “pitching chaos” Tigers (59.0) and the “Best bullpen ever?” Guardians (60.6). The Yankees come in at merely 46.5 percent.

Aaron Boone’s starter should have the edge in every matchup. But riding relievers has gotten the Dodgers this far, thanks in part to terrific run support from the team’s powerful offense, which has allowed Roberts to rest (and avoid overexposing) his high-leverage arms. And relief reinforcements may arrive in the persons of crucial lefty Alex Vesia and flamethrowing righty Brusdar Graterol, who’ve been angling to be added to the World Series roster. Graterol, who’s hardly pitched this season—he hurt his hamstring immediately after completing a comeback from shoulder discomfort—is a cipher at this stage, but a fully operational Vesia could help neutralize the Yankees’ lefty swingers. And the more relievers Roberts trusts, the less liable L.A.’s arms are to fall prey to fatigue or the reliever familiarity effect, and extend the trend of high-profile blowups by normally dependable bullpen monsters this month.

Both of these lineups are quite capable of chewing up pitchers: During the regular season, they finished first and third in the majors, respectively, in walk rate; first and second in chase rate; and third and fifth in pitches per plate appearance. Although neither team’s pitching staff was top-tier in earning chases, Yankees pitchers threw pitches in the strike zone at the majors’ lowest rate. Dodgers hitters should be happy to let them go by—which would be particularly true if Freddie Freeman looks more like his usual self.

By late October, almost everyone who’s still playing is a bit banged up, but Freeman’s late-September ankle sprain seriously impeded his performance in the first two rounds. When the injury wasn’t keeping him out of the lineup, it was hobbling him in the field and on the bases and limiting him to sporadic singles at the plate. Freeman’s first-base counterpart, Anthony Rizzo, is playing through pain himself, but he’s been much more mobile than Freeman, and he hit .429/.500/.500 in the ALCS, broken fingers and all. According to Freeman, rest has helped: Given that the Dodgers were in worse shape than the Yankees, they’ve probably benefited more from the break between series. Those four off days may make a difference for Freeman and Gavin Lux (who had a bad hip in the NLCS), in addition to providing time for Vesia, Graterol, and perhaps Miguel Rojas to work their way back. It seems safe to assume, though, that some or all of those players won’t be at their best; Rojas, for one, has to have offseason surgery.

It’s not as if the Yankees have been wholly unscathed. Gerrit Cole didn’t make his season debut until June 19; Giancarlo Stanton strained his hamstring, as Yankees GM Brian Cashman had foretold; Rizzo, Jasson Domínguez, Clarke Schmidt, Tommy Kahnle, and others missed months. But almost everyone returned in time for October. With Nestor Cortes seemingly set to be added to the World Series roster after recovering from an elbow injury, the only Yankees missing in action will be reliever Ian Hamilton (who hurt his calf in the ALCS) and a few marginal players who’ve either barely played this season (Jonathan Loáisiga), not played at all (Lou Trivino), or played so poorly that their absences seem like cases of addition by subtraction (DJ LeMahieu). If the Yankees don’t win, it won’t be because they weren’t at full strength. If the Dodgers don’t, they’ll have an excuse—not that they’ll use it.

When the Dodgers and Yankees faced off in the 1978 World Series, the Yankees’ staff was the one “held together by one huge roll of medical tape.” (Yankees manager Billy Martin was notoriously tough on pitchers’ arms.) Now, the roles (and rolls) are reversed, and the Dodgers’ rotation is running on fumes. Of course, the Yankees beat the Dodgers in six games in ’78. Maybe the outcome will be reversed this time, too.

It’s a testament to the Dodgers’ depth and talent—and, admittedly, their payroll—that they’ve won 105 games (and counting) despite so much going wrong. They’ve beaten two good teams in October with several arms tied behind their backs, and they aren’t even underdogs in this series, though they’d probably be favorites if they weren’t shorthanded.

“We’re gonna have enough pitching,” Roberts said in September of the Dodgers’ postseason approach. “The names might be a little bit different. I don’t think anyone knows who and who won’t be a part of it.” In that respect, the Dodgers’ pitching plan is in line with Tigers skipper A.J. Hinch’s recent observation about the perils of treating October too much like the preceding six months: “I think you see that the teams that win, they’ve had to veer off of their norm. I think that is the art of managing in the postseason.”

Roberts has veered from how the Dodgers drew things up out of necessity: No team’s plan survives first contact with the season, but the Dodgers’ order of battle has been distorted almost beyond belief. Yet they’re right where they wanted to be, thanks to Roberts’s string-pulling and L.A.’s substitutes stepping up. The Dodgers who are still standing seem to have rallied around each other in response to the vagaries of what Roberts has called his “most challenging season.” If they can keep overcoming fragility long enough for four more wins, it would probably be his most rewarding one as well.