Tim Walz and the Mankato West Dream Season That Will Live Forever

In 1999, Walz was the defensive coordinator who helped lead Mankato West High School on a storybook run to a state title. Now, he’s a vice presidential candidate campaigning in the final days before the election. Here’s the story of how Walz became “Coach”—and how the last few months have extended the glory days of his former players.They grew up playing on asphalt—touch football in the summer and tackle when winter snow arrived to soften their falls. They played everything, baseball and hockey and basketball, but they always loved football the most. They grew up, in the late ’80s and early ’90s, with the belief that they were special. That someday this collection of boys from the west side of Mankato, Minnesota, would achieve something that no one from their town ever had. “We always felt,” says Chuck Wiest, “like we were going to do something great.”

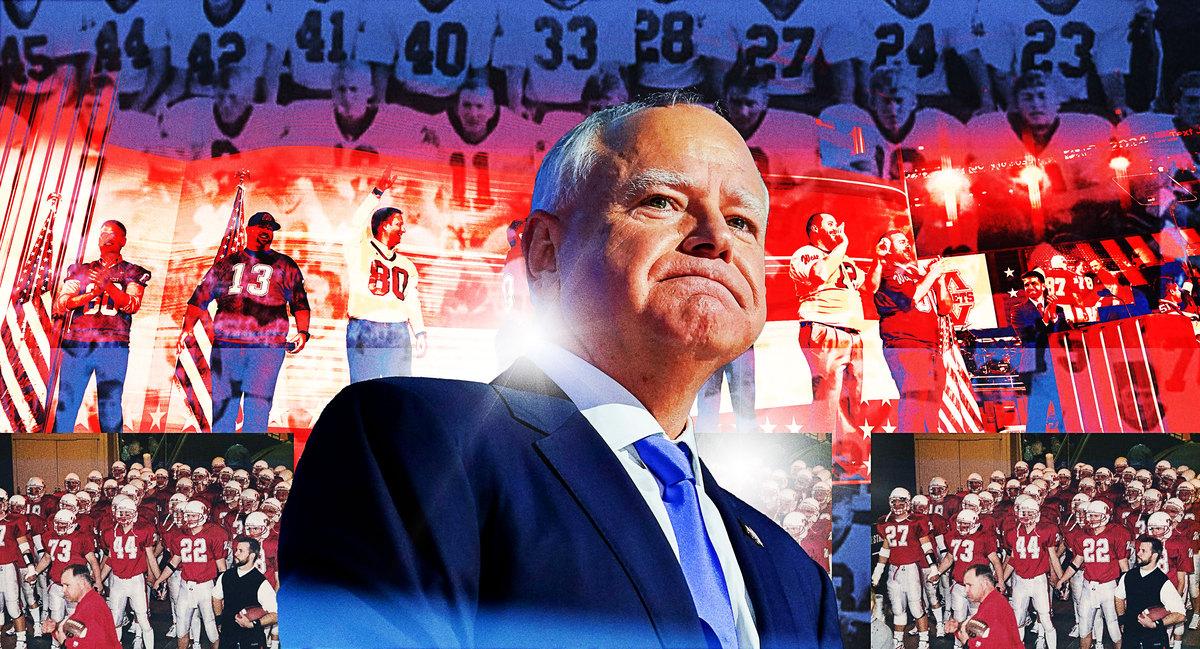

On a recent summer night, those boys reunited in a greenroom in Chicago, wearing old jerseys and searching their minds for lost memories of games played decades before. They were in their 40s now, and they’d come from around the country to be with the man who once shouted encouragement at them in the weight room, pushing them to finish one last rep. They weren’t the only people in that greenroom: John Legend walked by, on his way to sing onstage; Oprah Winfrey readied herself to speak; Bill Clinton stopped to shake a few hands. Suddenly, they were the most famous group of ex-jocks in the country. All because their high school defensive coordinator, Tim Walz, was about to accept the Democratic Party’s nomination to be vice president of the United States.

Current Vice President Kamala Harris had announced Walz as her running mate a couple of weeks earlier. And from the moment he joined the ticket, Walz has run not just as Minnesota’s governor, or as a plainspoken attack dog, or as the man who branded Donald Trump and J.D. Vance as “weird,” but also as Coach—the man this group remembers from his volume in the huddle and the weight room, from his impassioned encouragement on the sidelines and in the classroom. “Hearing him speak,” says Wiest, “the emotion and the passion, that’s just who he is.”

When Harris was initially considering Walz as her running mate, some within her campaign reportedly compared him to the fictional coach Eric Taylor from Friday Night Lights. Onstage, Harris rarely calls Walz Governor, instead choosing an apparently higher honorific. On the night of Walz’s convention speech, the United Center floor was filled with signs that read COACH WALZ, and onstage, he said, “I haven’t given a lot of big speeches like this, but I’ve given a lot of pep talks.” He went on to sum up the state of the presidential race in football terms. “We’re down a field goal,” he said, “but we’re on offense and we’ve got the ball. We’re driving down the field, and boy, do we have the right team.”

The framing makes sense. In a country that features a highly polarized electorate and a fractured media ecosystem, attaching your vice presidential candidate to football is among the simplest ways to reach a massive cross section of potential voters. According to polling, Walz has the highest net favorability numbers of anyone on either ticket, but the race remains deadlocked and could ultimately be defined by gender—polls point to Harris’s strength among women voters and Trump’s similar strength among men. The hope in the Harris campaign has been that Walz could change the calculus. He represents progressive ideas in a Midwest dad package; he’s an advocate for abortion rights who can draw up a blitz scheme and look comfortable dapping up a college football coach, as he did to P.J. Fleck at the Minnesota-Michigan game in late September.

Yet for the men who played on Walz’s most famous team, the Mankato West Scarlets, 1999 Minnesota state champions, the guy they see on-screen these days is merely a grayer version of the one who pushed them to relentlessly pursue the ball on every down. “Yeah, that’s Coach,” says Wiest, describing what it’s like to watch Walz’s political speeches. “That’s exactly what he sounded like in the huddle.”

Now, with Walz mired in what appears to be a toss-up election and standing days away from potentially winning the vice presidency, his former players and students say that these past several months have drawn them closer to politics—and even more strongly to one another. Group texts have emerged after decades of no contact. Reunions have sprouted up, both at the Democratic National Convention and back home in Mankato. Stories from the dramatic resurrection of the Scarlets’ program have been retold. Many are awed by Walz’s rise to fame but also unsurprised that once he entered politics, he marched straight to the precipice of the White House.

“It’s amazing,” says John Considine, an offensive tackle on that 1999 team. “And it’s completely surreal.”

Walz has spent most of this fall barnstorming around the Midwest, working to win over the ever-important “blue wall” states of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, and talking about football at nearly every stop. There was the trip to the Big House in Ann Arbor, which Walz called “a religious experience.” A stop in Green Bay for both a rally and a tour of Lambeau Field. A bus tour through Western Pennsylvania that included a pep talk to the Aliquippa High School football team.

Walz’s performance has felt familiar to Rick Sutton, his former boss at Mankato West. When Sutton interviewed for the West head coaching job in 1994, the program was a doormat for the bigger schools that dominated their league. Still, Sutton says, “You could see the potential was there.” Mankato was a growing town with highly engaged parents. Its enrollment was a decent size, with about 300 students per class. And at least a few of those students knew how to block and tackle.

Sutton’s tenure started miserably. The Scarlets endured a 1-22 stretch over the course of three years. But a few weeks before the start of the 1996 season, he got a call from the school’s principal, John Barnett. “We just hired this guy who used to be a football coach in Nebraska,” Sutton remembers Barnett telling him. “You should probably go talk to him.”

The day Walz and his wife, Gwen—who’d been hired at the school as an English teacher—arrived in town, Sutton went to their house to help them unload the truck. “It wasn’t really an interview,” Sutton says, “but we just talked. And the things you see in Tim now were evident then. He’s very, very genuine. He’s the kind of guy that he’s your best friend as soon as you meet him. And his enthusiasm was incredible. He was obviously very knowledgeable about football. So it was obvious that I wanted him on our staff right away.”

Walz signed on to be the team’s defensive coordinator—but he and the rest of the coaches knew they had a long way to go. “This is nonsense,” Walz recalled the staff saying to one another in his interview with Pod Save America’s Tommy Vietor. “Let’s just turn this thing around.” First, though, they had to gather enough players to field a team. West held no formal tryouts. Everyone who wanted to play was guaranteed a spot. “We were just trying to find enough bodies,” Sutton says.

One of those bodies was Eric Stenzel. Since elementary school, Stenzel had been the star athlete of his class, the biggest and strongest kid on any field, in any neighborhood, almost anywhere in the entire state. By seventh grade, he was already over 6 feet tall, and he had a frame that carried plenty of muscle and looked equipped to carry plenty more. Sutton called him up to varsity his freshman year, and he was immediately inserted as the team’s starting running back.

At 14 years old, Stenzel stepped onto the field against 18-year-olds every Friday night. “My first varsity game,” he says, remembering the 1996 season, “I got picked up and thrown to the ground like a rag doll.” West finished 0-8 that year and didn’t score a single touchdown through its first six games. “For most of the season, our leading scorer was a defensive tackle,” Stenzel says, “just because he got a safety in the first game.” West suffered one shutout loss after another, until finally, in the penultimate game of the regular season, the Scarlets scored a touchdown and fans rushed the field. But the game wasn’t over, so they were flagged for excessive celebration. West missed the extra point. Stenzel laughs, remembering the debacle of that season. “It was really bad,” he says.

While Walz led the defense, he also coached the running backs. And even as the team struggled, Stenzel says, “He was always so energetic and positive. He never got down on you. You loved playing for him.” Linebacker Dan Clement remembers Walz roaming the field during Clement’s JV practices, noticing every extra effort made by any player, rushing in to lavish attention and praise for a job well done. “He was always pumping me up,” Clement says. “I know he wanted to get me to be good so his team would be good, but he just gave me so much attention, even on the JV team, and it made me love being around him.”

Until the late ’90s, Mankato West football had no formalized offseason program. The school had a weight room, sure, but students had no real sense of when or how to use it. Sutton and Walz worked to change that. Even as freshmen, the class of 2000 spent long summer days down in “the dungeon,” as they called it, following personalized weight-lifting plans. “Everybody would bring one or two people, and then they would bring one or two people,” remembers Bryan Meger, an offensive lineman in that class. “Then it felt like, ‘Oh shit, I’m not there. What am I missing out on?’”

In 1997, West won a few games and showed that it at least belonged on the field with most of the teams on its schedule. And going into 1998, it seemed like the team had a roster full of players willing to make the commitment to be great—and a staff that was ready to help them do it.

On the fringes of that roster, though, was Clement, a senior linebacker who was both talented and angry. On the football field, he was violent. Off it, he was often drunk. “I was a scared little kid for so long,” Clement says now. “Then I started partying,” he says, “and I’m like, ‘Don’t worry, Dan. Life’s not that bad. You don’t have to be so angry anymore.’”

Clement made the all-conference team as a junior and started getting recruitment letters from colleges. Walz encouraged him, Clement says, to pursue a college football career. But the summer between his junior and senior year was “a shit show,” Clement says. He got arrested a couple of times for underage consumption of alcohol. The school year began, and his drinking continued. Going into his senior football season, he had to serve a suspension before he could play. “Fuck it,” he remembers thinking. “I’m just not going to play at all.”

That seemed easy enough. He could keep drinking, float through the school year, hopefully pass enough classes to graduate, then figure out what might come next. But every day, when Clement passed Walz in the hallway, his coach stopped him and delivered a simple message: “We need you.” Day after day, before school or during, wherever he saw him, the same refrain. We need you. We need you. We need you.

“He knew I was struggling,” Clement says. Walz never spoke with him directly about his drinking. “I don’t care about that other stuff,” Clement says Walz once told him. But Clement heard, in his voice, both an invitation and a declaration that he mattered. Finally, he decided to return to the team for the second half of that 1998 season, and he helped deliver the Scarlets their first win over crosstown rivals Mankato East in 11 years.

More than a decade later, when a friend of Clement’s got sober and encouraged him to do the same, Clement thought back on his high school experience and the encouragement he’d gotten from Walz. “The caring attention he gave, that positive support can pull you through really dark times in your life,” he says. By coming back to the football team, he says, Clement was telling Walz, “‘I’m leaning on you. I’m trusting you here. I think partying is a better idea. You don’t think so. And I’m going to trust you on that.’

“And he was right. I was wrong. And later in life, when I continued to do that, when I continued to trust other people who love me, then it led my life in this beautiful direction. Just like it did back then.”

On the field and in the classroom, Walz was perpetual motion at maximum volume. “He’d pull you aside,” remembers Clement, “and say, ‘Go hit ’em in the fucking mouth so we can go celebrate.’ It was like that. We don’t want to hit ’em in the fucking mouth to hurt ’em, but we want to win, and we want to celebrate winning.” Sutton could be an old-school screamer at practices and in games, like a fire-and-brimstone preacher using the sideline as his pulpit. But when Walz yelled, it was mostly to encourage. “It was kind of a good cop, bad cop deal,” says former defensive tackle Matt Laird.

At least most of the time. Nick Wiest (Chuck’s little brother) remembers a time when Walz got into a shouting match with a linebacker. “It was intense,” he says. “And when you think about it, it’s an adult in a shouting match with a high school kid.” Afterward, though, Wiest remembers Walz apologizing both to the player and to the entire team. “He owned up to it,” he says. And most of the time, when Walz needed to criticize a player, he took a gentle tone. Says Stenzel: “He could tell you that you’d done something wrong without ever making you feel small.”

In the classroom, Walz also made an immediate impact. “He really was everybody’s favorite teacher,” says Holly Mickelson-Whitney, a student from that era. “That’s not just rhetoric. Everybody loved him.” Walz taught social studies, working to connect students to the world around them, both at home in Mankato and farther afield. Often, students would file into the classroom and see the news playing in the background. Walz used the stories of the day to spark debate. “He brought up all these global topics,” says Sean Koomen, a student who kicked for the football team his senior year, “and introduced them to this small Minnesota farm town. He opened our minds.”

Mickelson-Whitney remembers that she was never able to tell where Walz fell on the political spectrum. She says he welcomed and challenged all points of view, attempting to teach students how to engage with someone whose opinions they didn’t share. “I think what people loved so much about him,” she says, “was that you really felt like he was listening to you and that your voice was heard.”

Outside the classroom, Walz found other opportunities to deepen his relationships with students, joining the staff of both the boys and girls basketball teams as an assistant coach. “I didn’t like him at first,” says Andy Thompson, who initially encountered Walz on the basketball court and later played for him on the football field. “Because he made me work very hard, and I was a big fat kid who didn’t want to run very much.” Over time, though, Thompson came to appreciate Walz. “He wouldn’t let you quit,” he says. “He made you go beyond what you think your abilities are.”

The basketball court was also where Walz got to know Anne Steffan, an outrageously talented athlete who struggled to embrace that piece of her identity. “It was different back then for girls who were really into sports,” Steffan remembers now. “I wasn’t exactly embarrassed by it, but I wasn’t always comfortable with showing the fact that it was my passion.” Steffan enjoyed basketball, but she loved softball, where she was a power-hitting shortstop who was getting recruited by schools across the country. She tended not to share with friends how badly she wanted to play college softball, though, worried about what it would say about her femininity. “When I wouldn’t let myself get excited, he got excited for me,” she says of Walz. Steffan went on to become an All-American second baseman at Nebraska. “He was the one who would celebrate these accomplishments that I was too self-conscious to celebrate myself.”

When the Scarlets showed up for the first day of fall practice in 1999, they had photos taped to each of their lockers showing the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome. Above it, two words were written: DOMEWARD BOUND. This seemed ambitious. To that point, West had never even reached the state tournament, much less the semifinals and finals, which were played each November in the Dome. But this group of guys had won at every level—middle school, freshman, and JV—and wasn’t concerned with their varsity program’s previous failures. “I never felt associated with those teams,” says Chuck Wiest. “It was more like, ‘What happens when we get there?’”

The Scarlets knew that their offense had enough talent to compete with anyone. And with a defense built around Stenzel, now a dominant linebacker, and led by Walz, they believed that side had the potential to do the same. West’s defense ran a 4-4 scheme that was geared toward stopping the run. (In a state where teams had to prepare for snow games in October, most every school built its offense around the run.) Nick Wiest remembers how Walz drilled into the inside linebackers’ heads that on every single play, their job was to read the opposing guards. “The quarterback and the running backs, those are your girlfriends,” Wiest remembers Walz saying. “The guards, they’re your mom.”

The distinction was important. “The girlfriends are going to lie to you,” Wiest remembers Walz saying. “They’re going to do a fake one way or another. The guards are your moms. They’re never going to lie to you. They’ll pull one way, and that’s the way the ball is going. They stand up to pass block, that means they’re passing.”

Walz also had a slogan: 11 to the ball. This was the defense’s mantra. On every snap, he wanted to see 11 helmets in rapid motion, moving to the ballcarrier and ending the play. He got T-shirts made emblazoned with the slogan, and every Friday, the defensive starters wore those shirts to school. If you lost your starting job, you lost your T-shirt. You had to fight in practice all week to earn it back.

The season started with a gauntlet, game after game against bigger and better-funded schools. Mankato West played in the AAAA classification, but many schools in their conference played in AAAAA. The Scarlets lost their first game to one of those larger schools, Rochester John Marshall, and afterward, Mankato West hosted a dance. “Girls and other students were coming up to us saying, ‘Well, you guys almost beat ’em, and you’re looking a lot better than our teams have ever looked in the past,’” Considine remembers. “But we didn’t want to hear it. Our expectations were a lot higher than that.”

After winning two of their next three games, West traveled to Faribault, a small town just south of the Twin Cities. Defensive tackle David Schoettler remembers Walz prepping them over and over for one play: a counter that Faribault would run until West proved that they could stop it. Sure enough, Faribault ran it right at Schoettler on the first play of the game and broke loose for a long touchdown. Schoettler remembers Walz pulling him aside on the sideline and saying, “You’re done.” He was benched for the rest of the night. Schoettler sulked. One play, one mistake, and that was it? But afterward, Walz talked to him. “It was like the ‘disappointed dad’ talk,” Schoettler says—gentle but direct. West lost that game 20-14, to a team that they knew had less talent. “How are we losing to this team?” Chuck Wiest remembers thinking. “What is going on with us?”

The next week they played Owatonna, a bigger school they’d beaten the year before. “They wiped the floor with us,” Considine says. Owatonna pulled their guards and ran sweeps in either direction on damn near every play. Final score: 42-7.

Following that loss, the team held a players-only meeting, trying to unlock the potential they knew still existed. “We have two paths we can go down,” Chuck Wiest remembers saying. “We can just end this season, maybe win a playoff game, and that’s it. That’s our senior year. Or we can do something special.” They needed to make a choice. “We weren’t sad,” says Considine. “We were angry.”

The next week, says Laird, “we had one of those rare moments where Walz lost his mind.” Someone made a mistake in practice. “And he got right in all of our faces,” Laird says. “I don’t remember exactly what was said, but I remember the very next play, whatever happened, the offensive player regretted it.”

Ahead of the team’s next contest, the “Jug Game” against crosstown rival Mankato East, Walz tweaked the defense. He dropped his beloved 4-4 and shifted West’s fastest linebacker, John Kozitza, to a “star” defensive back position, operating much closer to the line of scrimmage than the deep safety but farther off the ball than he’d been playing as a linebacker. East ran a spread option offense. “The defensive backs were instructed that we don’t care if there’s a pitch, we’re hitting the quarterback no matter what,” says Considine. On the first play of the game, the quarterback offered a fake pitch to the running back, but Kozitza never flinched. “He lifted him up off the ground,” Considine remembers, “and put him right back down into it.”

On the sideline, Walz and the players erupted. “That could have been a season-changing play,” Considine says. West won 21-0, and the game never felt that close. “It could have been 120 to nothing,” says linebacker Jimmy Baker. The Scarlets closed the season with a 31-24 win over Rochester Century, to finish 4-4. It wasn’t a dream season, but it was something. And with the postseason awaiting, they had new reason for hope.

In the week leading up to the playoffs, Walz was even more frenetic and loud on the practice field and in the locker room. “If he could have snuck pads on and gotten out there with us, he would have,” says Chuck Wiest. “His mentality was ‘I want to be out there with you. If I can do it, you can do it, and we’re going to do it together. Climb up this mountain with me so we can both be at the top.’”

All season long, week after week, players had returned to their lockers and seen the same image of the Metrodome. Now they had to win four games to get there.

They started the sectional tournament with back-to-back blowout wins, 55-0 over Waseca and 43-0 over Marshall. “I always felt like going into the next game,” says Baker, “the other team was screwed.” Walz’s defense had now pitched shutouts in three of its past four games. For the sectional final, they had to go on the road to play Worthington, a school with small but tough kids in an old manufacturing town. Again, West won with ease, 42-20.

For the first time in school history, they advanced to the state tournament.

Their first opponent: Totino-Grace, a private school up in the Twin Cities that was rumored to recruit athletes from nearby public schools. “No one in the world except us gave us a chance,” says Sutton. That week, the coaches tried to motivate the team by pointing out the contrasts between their two schools and programs. “Gentlemen,” Considine remembers the coaches saying, “let me read off the names of some of the players on this team.” And then they did: Spencer Cone. Jesse Linstroth. Tim Singewald. The players got the message. “They sounded like preppy kids,” says Considine.

Yet on the field, Considine says, “it was an absolute dogfight.” “I think at halftime I had a bruised stomach from getting punched and beaten. They were playing to the echo of the whistle.” The Scarlets trailed 8-7 at the half, but they felt like they had taken Totino’s best shot. They had. Mankato West dominated the second half, getting two touchdowns from running back Chris Boyer and another from Chuck Wiest to win 28-16. Afterward, they rode the bus back down to Mankato from the Twin Cities, bruised and elated. They’d done it. They were going to the Dome.

This, they believed, was the place they were always headed. To gather in this locker room, footsteps from where the Minnesota Vikings got dressed each Sunday. To run onto this turf, where they’d watched Cris Carter and Randy Moss terrorize defenses week after week. Now that they were here, there was little time to reflect on where the program had once been, on how much they’d changed the culture of Mankato West football. They didn’t care how many games the varsity had lost back when they were all freshmen. Even Stenzel, who was on that 1996 team, had long believed that this was where they would end up, that someday they’d be seniors finishing their careers in the Dome. “I knew we would be back in a week,” he says of his mindset going into the team’s semifinal game against Northfield. “This will not be our last game.”

And it wasn’t. West dominated the Raiders, winning 45-8 behind a suffocating defensive effort and a massive game from Chuck Wiest, who caught five passes for 175 yards and two touchdowns. That set up the final against Cambridge-Isanti.

The moments from that game are all fragments now, floating through memories 25 years hence. “Holy crap,” Schoettler remembers thinking before the game, finally allowing the reality to hit him. “We’re here.” Sutton remembers addressing the team, grasping for ways to communicate just how special this moment was, how much its imprint would linger in the long arc of their lives. “Enjoy it,” he remembers telling them. “In life, you don’t get to do things like this very often. You get to play old man softball when you’re 50. You get to play pickup basketball forever. But you don’t get to play football. You don’t get to do what we’re about to do.”

Chuck Wiest remembers his second grade teacher, someone he hadn’t seen in many years, coming up to him. “The whole community, everybody was there,” he says. Special teamer Adam Segar remembers standing on the sideline and looking up at the jumbotron, in disbelief that he was watching his teammates on such a massive screen. Sherri Blasing, Mankato West’s principal and Walz’s neighbor, remembers sitting in the stands, eyes glued to Walz on the sideline. “My husband looks at me and he goes, ‘Tim has not stopped jumping straight up and down through the whole game. He’s just going to die after this game or something. He’s just so intense.’”

West controlled the game but never pulled away. Calen Wilson returned a punt 93 yards for a touchdown. Boyer ran wild, rushing for 202 yards and three touchdowns. But Cambridge-Isanti hung close until the end, when Jacob Schmiesing intercepted a fourth-down pass to seal a 35-28 win. Sutton remembers Walz and the other coaches coming together for a giant group hug after the interception. Considine remembers unbridled delirium in the locker room, so much excited energy with so little idea of what to do with it. “We were just ecstatic,” he says.

The team rode back to Mankato that night with police escorting them to the high school, where a packed gym of people waited, screaming their names. No one can quite remember whether they took time to reflect on all the losses the school had suffered when they’d been too young to compete. No one quite remembers whether they speculated about how long this win would stick with them, or whether they imagined some future versions of themselves coming together to think back on this moment, on this night, when they were briefly invincible, the boys who’d accomplished something no one from their town had ever done.

“It was,” says Considine, “just kind of a blur.”

Twenty-five years later, these men wear baggy shorts and old jerseys, baseball caps to cover bald spots and loose-fitting hoodies over early-middle-aged paunch. They are talking and laughing on the track in the corner of Mankato West’s stadium, footsteps away from the field they last played on decades ago. “I was a little nervous about this,” says Stenzel, who, if not for the flecks of gray in his beard, looks like he could still put on pads and patrol the middle of the defense. “You never know how this sort of thing is gonna go.” It’s the anniversary of the 1999 team’s championship, and they’re back to be honored at halftime of the Scarlets’ clash against Waconia.

Some have scattered around the country. Stenzel went on to play for the University of Minnesota, Chuck Wiest at North Dakota State. Even the kicker Sean Koomen went on to play at Division III St. Olaf’s College. Nick Wiest lives in California, his brother Chuck in Montana. Baker moved to Hawaii before returning to Mankato to raise his kids. Long after they left, though, subsequent teams worked to uphold the standard set by the ’99 champions. West won another state title in 2002, with Sutton and Walz still on staff, and three more after those coaches had moved on, in 2008, 2014, and 2021. Today, it’s considered one of the elite programs in the state.

There was talk, coming into the night, that Walz might show. He had made a campaign stop earlier in the day in Wausau, Wisconsin, just a five-hour drive or a short flight away. His rise to political prominence has left his old players in shock. “Surreal” is the word they use, over and over again. Some are into politics, but many aren’t. Still, they’re thrilled by the new stardom of the man who’d once pushed them to be the best version of themselves.

Clement says he usually votes third party but can’t wait to vote for Harris, largely because of the fact that she chose to run with Walz. Baker says, “I’m not a huge political guy, not by a long stretch. But what I look for in a president or politician and what I hope for is that at the end of the day, my kids can look at that person as an example. This is how I should live my life. And I think [Walz] is perfect for that. He exemplifies everything that I hope that my daughters would look for as a man anywhere, and the kind of guy I would like my son to grow up as.”

Several members of the 1999 team had made it to Chicago for the DNC in August. Many others were hoping to reconnect with Walz the night of the reunion. But as the game wears on and it becomes clear that the potential vice president isn’t going to make it (he did later return to do the pregame coin toss ahead of this year’s “Jug Game” against Mankato East), they content themselves by catching up with one another. They talk about their kids: Considine’s daughter is a star shortstop; Meger’s son is getting ready to make his varsity football debut. They talk about the calls they’ve gotten since Walz was announced, the reporters now so interested in this long-ago chapter of their lives. And they talk about Walz.

“You want to run through a brick wall for him,” says Meger.

“He was so energetic and positive,” says Stenzel. “He never got down on you.”

“I played,” says Clement, “for him.”

The air is thick, a little humid, and the sky is swirling oranges and blues. It cools as the first half ends and the sun sets, and they turn their attention to the game, watching a new generation of Mankato West Scarlets come back from 14 points down to win. Afterward, some talk about heading downtown, hitting the bars. Others joke that it’s already past their bedtime at 8:30 p.m. They don’t know when they’ll see one another again. Maybe they’ll have another reunion 25 years from now. Maybe Walz will be there. By then he’ll be in his mid-80s, either a former vice president or the answer to a trivia question, but still their coach, then and now and always.

Considine says he supports Walz’s candidacy, but he’s more grateful for the excuse to talk to guys he’d long ago lost touch with. To reconnect not only over the newfound fame of the man who coached them, but also over all that they accomplished in that fall of ’99. To celebrate a high school team that will live on forever—and whose legacy has transcended their wildest dreams. “Now we have a reason to talk about our glory days,” he says.