We could tell two contrasting stories about the 2024 Los Angeles Dodgers, who won the World Series with a wild Game 5 comeback against the Yankees on Wednesday night in New York. Let’s try each tale on for size.

Version 1: The Dodgers splurged on stars, committing more than $1.5 billion over the past few years to extend trade acquisition Mookie Betts and sign free agents Freddie Freeman, Shohei Ohtani, and Yoshinobu Yamamoto in the franchise’s quest to construct a superteam. All went according to plan. The 2024 Dodgers were the best team in baseball during the regular season, and key contributions from that costly quartet propelled them to a title. Ohtani was the National League’s most valuable player, Betts led the Dodgers in October OPS, Yamamoto delivered their best start of the World Series and two of their four strongest of the postseason, and Freeman won World Series MVP.

Version 2: The Dodgers splurged on stars in their quest to construct a superteam. Little went according to plan. The Dodgers recorded their worst winning percentage in the regular season since 2018, which was years before Betts and the rest joined the roster. Speaking of Betts: He was pressed into service as their starting shortstop, before he got hurt and missed almost two months. Their rotation, projected to be baseball’s best, instead finished 20th in FanGraphs WAR. They lost so many starting pitchers to injury that 58 percent of their postseason innings were thrown by relievers. Johnny Wholestaff started Game 6 of the National League Championship Series and World Series Game 4, and the last contest of their season effectively became a second consecutive bullpen game when starter Jack Flaherty was knocked out after recording only four outs.

Here’s the twist: These are two tellings of the same story. In some respects, this season definitely didn’t unfold the way the Dodgers drew it up. In other ways, it went exactly as they’d desired. The Dodgers’ record fell short of its ceiling over the first six months of the season, but by signing those superstars and surrounding them with a strong supporting cast, owner Mark Walter and POBO Andrew Friedman raised that ceiling so high that the team’s floor—like its depleted October roster—was still championship caliber. Despite being slowed by what Freeman referred to as “every speed bump possible”—and, in the process, amassing the majors’ most injured list time—the wounded, shorthanded Dodgers were good enough to be better than everyone else during both the regular-season marathon and the postseason sprint.

“This game was no different than our entire season,” Max Muncy said after Game 5. “Get dealt a couple blows, come back from it.” But even if the Dodgers “didn’t plan it out this way,” as manager Dave Roberts remarked, the result was what they wanted: a totally untainted title that cements their status as a modern-day dynasty. As Walker Buehler said moments after setting the Yankees down in order in the ninth inning of Game 5, “Everybody talks shit about 2020 and whatever, but they can’t say a whole lot about it now.”

Or, at least, they shouldn’t. Then again, L.A.’s 2020 title arguably should have been unbesmirched already. The Dodgers were by far the best team during the COVID-shortened 2020 regular season, leaving next to no doubt that they would’ve made the playoffs if they’d played 162 games instead of 60. And if anything, their path through that postseason was harder than it would have been in a normal year. Because the playoff field was expanded to 16 teams, L.A. had to beat the Brewers in a best of three just to get to the division series. And starting with the division series, games were played at neutral sites, depriving the Dodgers of true home field advantage.

But yes, that was a weird season, and so the Dodgers needed to be the last team standing one more time, to show that they could do it in a year with fewer fans made of cardboard and to top off the win with a parade. Now that they’ve sealed a second series victory under Roberts, you do, in fact, have to hand it to the Dodgers—much like the Yankees handed the Dodgers Ws in Games 1 and 5. “I’m sure there’s no asterisk on this one,” Roberts said after the game.

As comments like that one make clear, everything the latter-day Dodgers do is viewed in light of what earlier editions of the Dodgers didn’t do. Those frequent comparisons come with the October territory when you reel off the third-longest postseason appearance streak in MLB history, but they can be a bit misleading. As a franchise, the Dodgers have been postseason staples for a decade, but individual Dodgers have come and gone (in some cases, multiple times). Clayton Kershaw is the only 2024 Dodger who’s been on the team continuously since that streak started, and he missed most of the 2024 regular season and the entirety of the playoffs. (No wonder L.A. won! Sorry, low blow.)

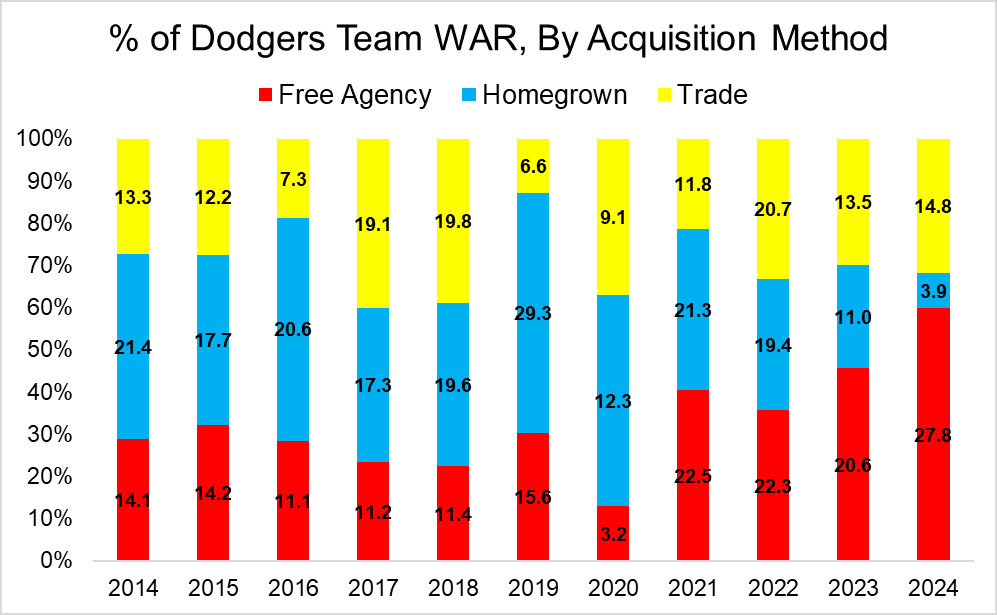

This year’s Dodgers were different from the 2020 champions not only because they featured some fresh faces, but also because their semi-uncharacteristic offseason spending spree cemented a marked shift in the composition of the club. The graph below breaks down the Dodgers’ Baseball-Reference WAR into three buckets, based on how the players who produced it were acquired: WAR from big league free agents, WAR from homegrown players (as in, those who were acquired via the draft or amateur free agency), and WAR from players acquired by trade (or waiver claim, purchase, or Rule 5 pick). The bars represent the percentage of team WAR made up by each category, and the numbers indicate each subset’s actual WAR total.

Check out the change in the relative heights of the blue (homegrown) and red (free agent) bars, in particular. Until recently, the Dodgers’ homegrown players usually outproduced their free agents or at least held their own. This year, they didn’t come close. The 2020 team (which was among the more homegrown-centric contenders that year) got way more WAR from homegrown guys in 60 games than this year’s group (the least homegrown team in the 2024 tournament) did in a full-length season. The only homegrown players who made contributions in Game 5 were Buehler (an impending free agent), Gavin Lux (the no. 9 hitter), and Will Smith (who signed a sizable extension of his own this spring). The Dodgers’ track record of adept drafting and development has helped them afford and seduce superstar talent—Juan Soto, Roki Sasaki, or Corbin Burnes could be next—but it’s no longer paying huge direct dividends.

If you still want to find fault with the Dodgers, you could say that the 2024 team didn’t have to tangle with any truly formidable opponents. You could say that the Yankees gave games away. And you could say that compared with past editions of the Dodgers, this one paid to win—not that there are necessarily less or more righteous ways to win a World Series.

Or, for that matter, foolproof ways to win one, however high one’s payroll.

After suffering the most playoff pain of the 2010s, the Dodgers set a record in 2022 and 2023 with the most wins (211) in a two-season span by a team that didn’t make the championship series in either year. They were, per Friedman, a failure—which made them more appealing to Ohtani, who envisioned an alliance between the league’s best regular-season player and team that would bring both parties elusive postseason success. (Or, in Ohtani’s case, at least an elusive MLB postseason appearance.)

It took a single season for Ohtani’s move from one “L.A.” team to another to have the hoped-for effect, probably putting an end to Friedman self-flagellation. What a difference a second championship makes. “For our organization, we deserve this,” Buehler said. “We’ve been playing really good baseball for a lot of years.”

Buehler is right: Two titles in 12 years is almost exactly what the Dodgers deserve. The table below shows the Dodgers’ probabilities of winning the World Series in each season since their playoff appearance streak started in 2013. The column labeled “preseason probability” reflects the team’s World Series odds as of Opening Day; the column labeled “postseason probability” displays the corresponding odds as of the end of the regular season. The numbers in the bottom row represent cumulative totals—as in, the number of championships the Dodgers should have been expected to win. (All of these figures primarily come from FanGraphs—whose playoff odds date back to 2014—with Baseball Prospectus’s odds subbing in for 2013.)

Dodgers Preseason and Postseason Championship Probabilities, 2013-24

Based on the odds on each Opening Day, the Dodgers “deserved” to win 1.7 championships over this dozen-year span. And based on the odds when each postseason started, the Dodgers “deserved” to win … 1.99. In other words, given the hands they held in each of those 12 seasons, the most reasonable expectation was two titles. And when have sports fans been known not to be reasonable?

Without falling prey to the gambler’s fallacy, I suppose we could say that the Dodgers were due. By winning this series, they erased the stain on their October record—statistically speaking, at least. Had they lost, they would’ve had half as many championships on their recent résumé as they “should” have. Instead, they’re right on target—which isn’t to suggest that their old losses don’t still sting.

The lesson, of course, is to keep at it. The only predictable quality of the MLB playoffs is that you can’t win a World Series without making it to October. “We did go through a lot … but one thing is that we just kept going,” Roberts said after Game 5, referring specifically to the 2024 Dodgers but just as aptly describing the Dodgers of the past decade. Keep putting together great teams. Keep qualifying for the playoffs. Keep showing up for those bingo games, and eventually, your winning numbers will be called. Over a sufficiently large sample of small samples, the results may even out.

Most teams don’t make enough playoff appearances for that truth to be demonstrated. The Yankees have had the second-most regular-season wins during the Dodgers’ postseason streak—and also, for that matter, over the 15 seasons since New York last won a World Series—but unlike the Dodgers, they haven’t made it to October every year. (They missed the playoffs in 2013, 2014, 2016, and 2023.) Nor have they consistently assembled squads that entered October as favorites, as the Dodgers and Astros have. Fans of most teams would gladly sign up to lose like the Bombers, but there’s always a bigger fish: Privileged as they are, Yankees fans can perhaps be forgiven for feeling some superteam envy when they look at L.A. The Dodgers’ perpetual playoff machine will have to break down someday—right?—and the fact that they fielded the oldest hitters and seventh-oldest pitchers in the game this season might be a disconcerting sign. But it’s tough to bet against them, considering the prospects of improved health and two-way Ohtani in 2025.

In mid-September, during a lackluster stretch for the Dodgers that briefly appeared to put their march to another NL West title in jeopardy, Betts conceded that the team’s pitching injuries had taken a toll on morale. “It does suck,” he said, before adding, “It’s no excuse.” You won’t hear Betts or his teammates making excuses now, either. After winning this World Series, the Dodgers don’t need them.

Thanks to Ben Clemens of FanGraphs and Kenny Jackelen of Baseball-Reference for research assistance.