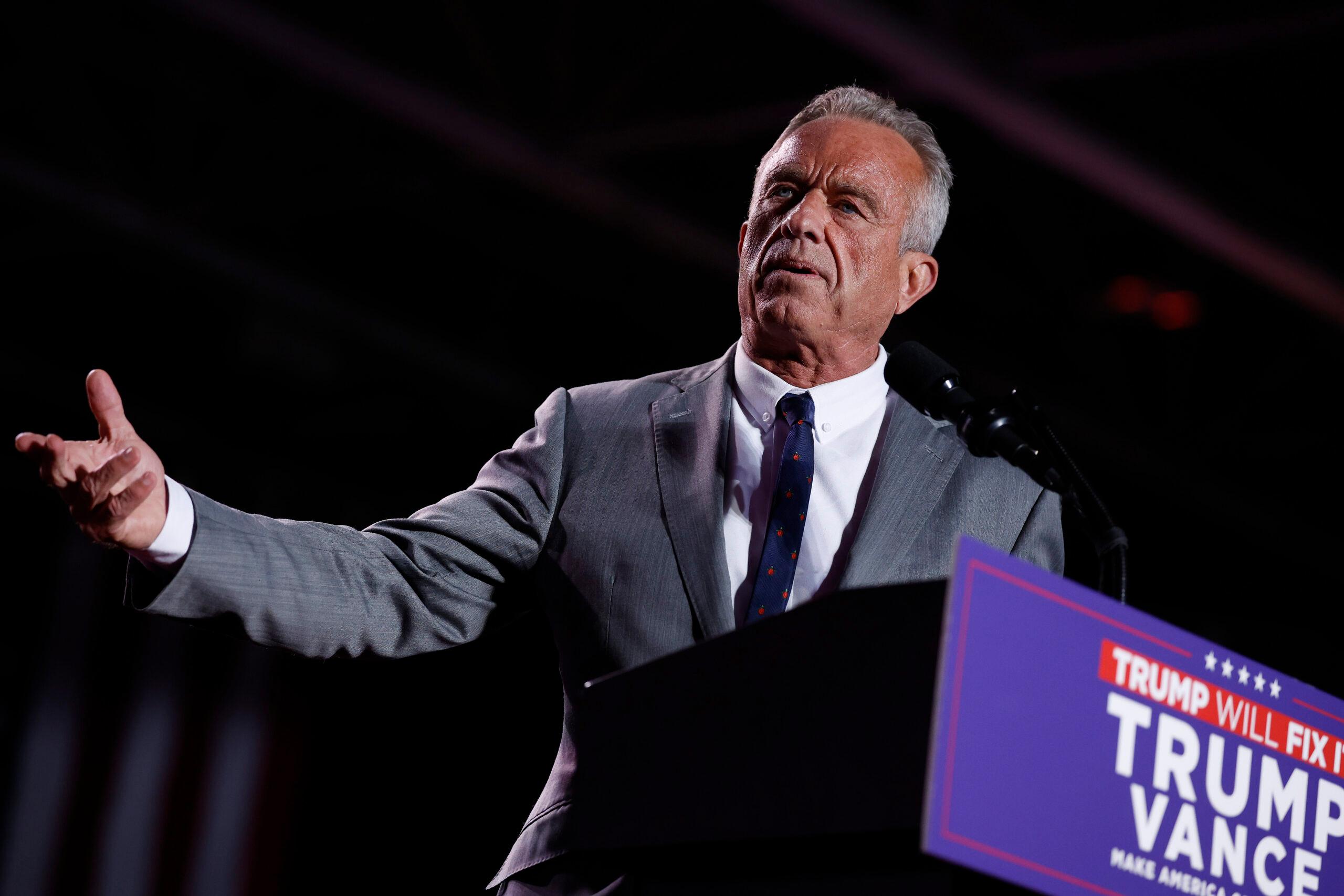

Vaccine Conspiracies, Fluoride Myths, and America’s Broken Public Health Discourse

Brown economics professor Emily Oster joins the show to talk about Robert F. Kennedy Jr., his fluoride and vaccine theories, and how the media and science community should treat the most controversial topics

Emily Oster, professor of economics at Brown University, joins the show to talk about Robert F. Kennedy Jr., his theories about fluoride and vaccines, and how the media and science community should treat the most controversial topics. This is a new age of science and information, where trust seems to be shifting from institutions like the FDA and CDC to individuals like RFK Jr. and Oster, and I consider her a model of public health communication.

If you have questions, observations, or ideas for future episodes, email us at PlainEnglish@Spotify.com.

In the following excerpt, Emily Oster and Derek dive into how economics relates to public health communication and the debate about whether to reopen schools during the pandemic.

Derek Thompson: You’re a professor of economics. You’re also widely known as a public health communicator, whether it’s your books about pregnancy and parenting or your commentary about the pandemic and other public health issues. How do you think economics can make people smarter about public health?

Emily Oster: The kind of economics that I’m most interested in is the kind where we analyze data and we try to understand what data is telling us. And the other really important piece of economics is decision-making, weighing costs and benefits. And in my mind, those are both really key in how we talk about, communicate about public health and how we evaluate the public health advice we give. There’s a piece where we really want to understand what the data says about something, and then we want to communicate that out to people. And at the same time, we want to think about the costs and benefits of any of the advice that we’re giving. So for me, economics is really core to all of this discussion.

Thompson: These costs and benefits, the trade-offs, I think, that economics seems to bring to the fore are really important, right? Economics says: You raise taxes. That’s good. Now you have more revenue. But there’s a trade-off. It’s not just more revenue. Those taxes also discourage activity. Trade-off here, trade-off here. And public health is a set of interventions, and interventions are rarely all good or all bad. So, for example, during the pandemic, you were very influential and, in some corners, controversial for calling for the reopening of schools. Do you think this was a good example of people in the public health space failing to think deeply about trade-offs, costs and benefits at play when it came to the policy of school lockdowns?

Oster: Yes and no. So I think initially, there was a lot of disagreement and misunderstanding around the data, so around how risky was it to open schools. And this is a place where I tried to positively contribute to the body of evidence and where I think, initially, maybe reasonable people differed. I think ultimately it became pretty clear the schools were not a source of substantial spread. As time went on and that became more clear, I think we did get into a place where the cost-and-benefit argument started to fracture a bit between how an economist would think about it and how public health was thinking about it.

For my mind, there was a potential cost. If everybody gets together, there could be some cases spread in schools; certainly some were. But there was an enormous benefit to opening schools, which is that it was the right thing for kids. And I think in the public health language—and this was an argument I heard a lot at the time—it was much more what economists would call lexicographic, caring only about one thing, which was the amount of COVID, and never wanting to think about the risks on the other side, only thinking about the risks in front of you. And I just don’t think that’s a good way to make decisions.

Thompson: And correct me if I’m wrong: One of the contributions that you made to this debate is that you gathered a lot of data that people could use, so that whether or not people were going to think lexicographically, if that’s an adverb that I maybe I just made up or ...

Oster: Oh, totally. That works.

Thompson: ... if they were going to think more, “OK, this is about a classical economic weighing of costs and benefits.” Well, the thing you have to do before you even get to that debate is have all the data on the table, right?

Oster: Yes. I believe that the thing that we needed to have in front of us was the data so we could have a reasonable discussion about this question. But I will say that if you have the view that the only thing, 100 percent of your goal is not ever spreading COVID in this particular case, then, actually, you don’t really need data because it wouldn’t matter how costly it was for kids to be out of school because it’s infinitely costly if even one person gets COVID. My view on this was: Actually, the benefits to opening school are quite real, and therefore we do need to understand the size of the cost. And that’s why it’s so important to get data on how much COVID is spreading in schools because we need to weigh the costs and benefits. If you’re not interested in weighing the costs and benefits, maybe it’s less interesting to have evidence.

This excerpt was edited for clarity. Listen to the rest of the episode here and follow the Plain English feed on Spotify.

Host: Derek Thompson

Guest: Emily Oster

Producer: Devon Baroldi

Subscribe: Spotify