Welcome to the Golden Age of Licensed Video Games

Video games based on movie or TV IP were once routinely terrible. How did they finally get good?More than any of the 21 prior Indiana Jones video games, Indiana Jones and the Great Circle grasps the art of the reveal. The latest Indy title, which was released for PC and Xbox on Monday, is chock full of them. In the opening section, a resplendent recreation of Vatican City, Indy comes across a fountain guarded by stone dragons. One puzzle later, and the fountain is rotating to reveal another puzzle, this time an ornately sculpted stone tableau. Deeper and deeper the famed archaeologist ventures into a series of geographically disparate subterranean labyrinths, each dislodged door revealing fresh, immaculately lit wonders of the ancient world. Such is the strength of the audio-visual presentation, you can practically smell the musty air that has not touched human nostrils in hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

These nested reveals are just one of the many ways in which Swedish studio MachineGames understood its assignment. To the extent that I can make such an assertion having played only a handful of the 22 Indy games listed on Wikipedia (including, crucially, the 1992 fan favorite point-and-click adventure Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis), The Great Circle is likely the greatest Indy game ever made. It has duly garnered stellar reviews. “The best Indy’s been since The Last Crusade,” Katharine Castle enthused for Eurogamer. Luke Reilly, writing for IGN, called The Great Circle an “irresistible global treasure hunt and far and away the best Indy story this century.”

The Great Circle joins the swelling ranks of recent licensed games done right. The Great Circle isn’t the only example based on a Lucasfilm property: Respawn’s third-person Star Wars Jedi titles, 2019’s Fallen Order and 2023’s Survivor, are both a big step up from comparable saber-wielding titles of the past two decades, such as 2008’s Star Wars: The Force Unleashed. Ubisoft Massive’s open-world adventure Star Wars Outlaws has undergone plenty of post-launch gameplay tweaks since its release this past August, yet as a Star Wars simulator, one that lets you simply live in a beloved universe, it nails the brief.

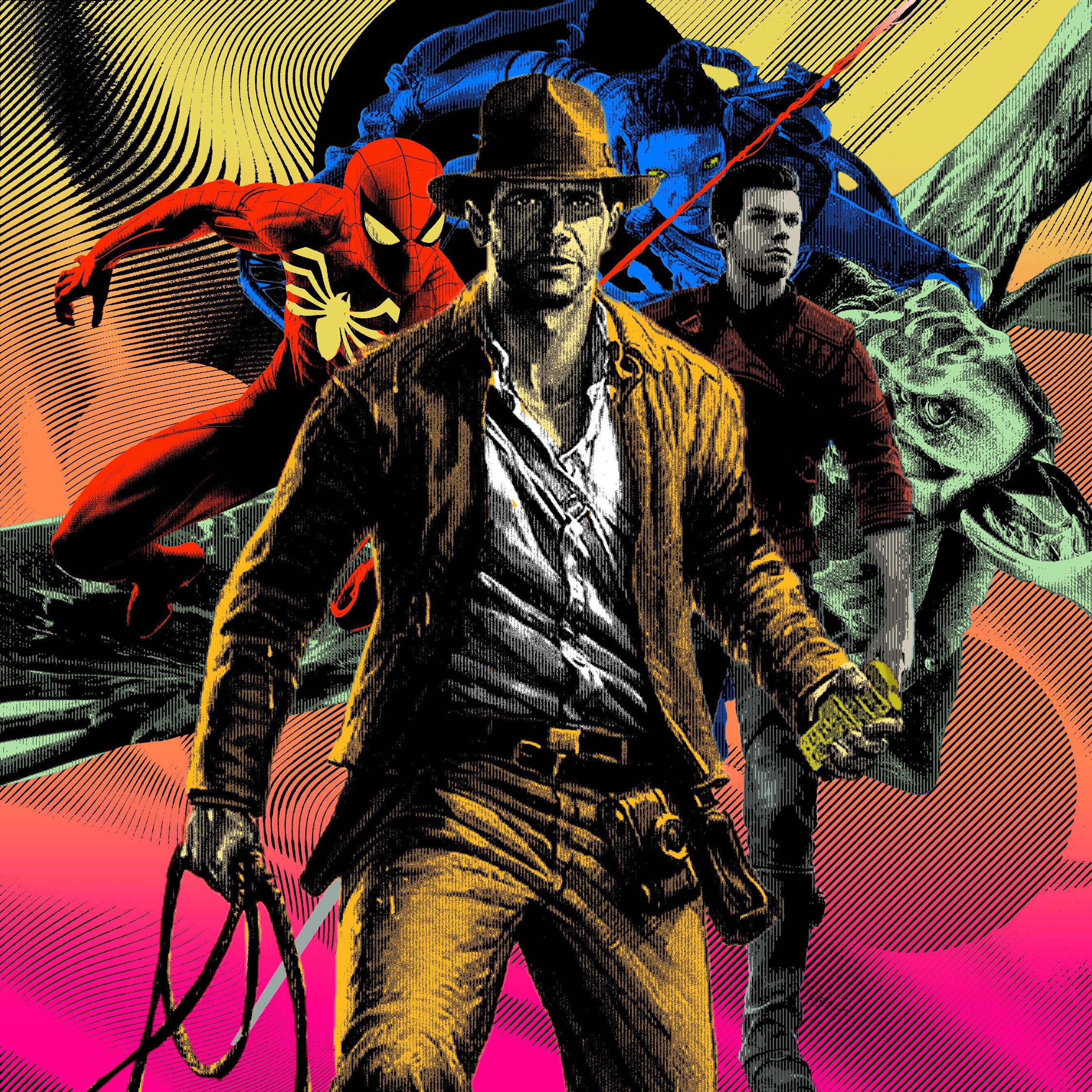

Last year’s Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora, also by Ubisoft Massive, gives players a vast, beautifully rendered version of James Cameron’s breathtaking (and record-breaking) Avatar universe. In moments of furious, physical, first-person action, the game tasks players with blowing up human infrastructure in the role of, essentially, a Na’vi ecoterrorist. Frontiers of Pandora does not pull its punches, either thematically or mechanically. Since 2018, Insomniac’s Marvel’s Spider-Man games—technical showstoppers infused with the effortless, breezy personality of a summer popcorn flick—have delivered the core fantasy of embodying the arachnid superhero, and then some. Operating at a scale just below these triple-A efforts, 2023’s RoboCop: Rogue City is an explosive action-shooter punctuated by brilliantly satisfying detective work.

In short, licensed games have never been better from a creative standpoint. In fact, titles based on non-gaming IP are enjoying nothing less than a golden age as studios make smart, evocative use of famous franchises.

For those who spent parts of the 1990s or 2000s playing abject licensed games (such as 2006’s dire The Sopranos: Road To Respect), the recent uptick in quality is striking. Sure, a few highlights from that era stand out: Spider-Man 2 (2004) was the first video game to truly impart a sense of the masked hero’s web-slinging locomotion; The Chronicles of Riddick: Escape From Butcher Bay (2004) delivered a gritty, immersive first-person shooter based on the Vin Diesel vehicle. (A large cohort of the Riddick dev team would stick together and eventually make the latest Indy adventure). But the vast majority were bad—really bad: essentially reskinned versions of better games rushed out of a publisher's door to coincide with a movie’s launch.

I subscribe to a broad definition of art, but a game such as Catwoman (2004) tests even my own expansive criteria, expressing grimly little beyond the profit-driven interests of studio heads and the joyless conditions of its making. Catwoman and its ilk are perhaps better thought of as expensive marketing initiatives intended to drive audiences to the theater. They are also merchandise, except of an interactive type that somehow manages to capture even less of the imagination than a static plastic figure.

“‘Licensed game’ has meant so many things over the years,” says Jeff Gerstmann, former editorial director at GameSpot during the 1990s and 2000s, and cofounder of Giant Bomb. “It became a scarlet letter—like, ‘Oh God, this going to be horrendous because they spent all the money acquiring the license and didn’t leave any money to make a decent game.’” Gerstmann sees this trend going all the way back to the 1980s with titles such as The Uncanny X-Men, released in 1989 on the NES: “Just a profoundly terrible game,” he says.

Today, that kind of unbridled awfulness is mostly a rarity; typically, the floor for licensed games isn’t much lower than, say, October’s A Quiet Place: The Road Ahead, which drew mixed reviews but had its passionate proponents. (One notable outlier is 2023’s so-called “worst video game,” The Lord of the Rings: Gollum). “The competition is much greater now,” says Piotr Latocha, director of RoboCop: Rogue City. “Even 15 years ago, the market was much easier. Game makers could drop an IP, make a very basic game, and it would still sell. Now that isn’t the case.”

Media giant Warner Bros. found out the hard way how fickle the current market can be. In February 2023, Hogwarts Legacy, the open-world take on the Harry Potter franchise, was released to much furor. Middling to some critics, magical to others, the game was duly lapped up by a global legion of Potter fans, selling more than 30 million copies and earning well over $1 billion. It was followed in February 2024 by Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League, a live-service open-world shooter that, while competent enough, was met by a distinct lack of enthusiasm from press and players alike. Later in the year, Warner Bros. wrote off Kill the Justice League as a $200 million disaster. In the weeks bookending Thanksgiving, the game was on sale for less than the price of a beer.

Together, Hogwarts Legacy and Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League represent a parable for the allure and pitfalls of the modern licensed blockbuster. Succeed in adapting a non-gaming IP—ideally one with a fervent, multi-generational fan base—and the ceiling of financial success can scarcely be higher. Fail—for any number of reasons, from the poor quality of a particular title to broader IP fatigue—and the results can be financially disastrous, not least for developers who stand to lose their jobs in subsequent budget cuts (which is what happened at Rocksteady, the Warner Bros.–owned studio behind Suicide Squad).

For what it’s worth, Warner Bros. doesn’t seem deterred: The company plans to keep promoting its IP’s potential in the interactive realm. And even if the odd flop flows from those efforts, no one will confuse the current landscape for licensed games with the bad old days of decades past.

It is the middle of a famously bleak U.K. winter in 2004. Andrew Curtis, director of Catwoman, is making his daily hour-and-a-quarter drive from Edgware, a small town in the suburbs of Greater London where he works, to hip Brixton, where he lives. It is nearly midnight, and the game maker is battling rain and snow with a belly full of Domino’s pizza. He is working overtime on one of the most notorious licensed projects ever made. Curtis describes the project, developed by Argonaut Games and published by Electronic Arts, as his “war story.” By the time the game shipped in July 2004, his entire team was “demoralized.”

Catwoman is an example of what Curtis calls the “day-and-date movie game,” an approach he blames for yielding some of the more “cursed” titles in all of licensed history. Typically, strict creative constraints were imposed on studios, such as following the movie’s plot (even if it didn’t make sense for a video game) and sticking to tight time frames in order to release alongside the film. The Catwoman tie-in game came about because of what Curtis understatedly describes as a “late request.” The movie, starring Halle Berry, was scheduled for release in just six months when the game got off the ground. Curtis admits he was “surprised” EA had greenlit the project because, as should have been clear to everyone, “six months is an insane development cycle for a game.” With access to the movie’s script, he and his team moved “quickly into crunch.” At the end of the development period, Curtis remembers thinking, “for six months, that's a possible seven out of 10—maybe.” It wasn’t. (Nor was the widely panned film, which failed to recoup its $100 million budget.)

In 2004, Gerstmann, then working at GameSpot, described Catwoman as a game whose “sharp graphics are offset by bad control, weak voice work, and shoddy gameplay.” Today, he sees it as an example of companies formulating “what would become the transmedia strategies of the future”—a lofty goal that nonetheless yielded mostly generic action games at the time.

Both Gerstmann and Curtis single out 2003’s Enter The Matrix as an interesting, if only fleetingly successful, example of a licensed title from the 2000s with marked creative ambitions. It follows Ghost and Niobe, two minor characters from The Matrix Reloaded, whose story wraps around that of the movie. It was pitched to Gerstmann as “transmedia,” one of the first times he’d heard the term from a publisher. The game’s story may have been inconsequential and largely uncompelling (“not even a B-plot,” deadpans Gerstmann, “more like a C- or a D-plot”), but “at least it felt as if they were trying to reach for something.”

Curtis sympathizes with the constraints the developers at Shiny Entertainment, the studio behind Enter The Matrix, were likely laboring under. “If something goes wrong creatively or technologically, then because of the fixed timeline, you have to cut content.” Curtis points to what he describes as the game’s “garbage” final level, in which Ghost and Niobe, while aboard their ship, the Logos, are being pursued by Sentinels in the dystopian real world. “It’s a perfect example of the kind of compromises that developers had to make,” says Curtis. “You’re just flying down tunnels.”

The development of Catwoman stung for Curtis all the more because, a few years prior, he had helmed an adaptation of John Carpenter’s 1982 horror movie The Thing. Curtis and his team at Computer Artworks were given the freedom to devise an all-new story. There was a sense at Computer Artworks that the studio had been cherry-picked by Universal: Their previous game was an acclaimed squad-based shooter called Evolva, and the studio’s founder, the famed digital artist William Latham, had produced cutting-edge generative screensaver art that looked like grotesque mutating organisms. This type of adaptation is one that Curtis describes as a “disconnected film IP game project,” in which developers aren’t restricted to a specific movie plot or release date.

For The Thing, Curtis was handed “no style guide.” It helped that the IP was, by the early aughts, practically a historical artifact in pop culture terms, albeit one whose renown and, just as importantly, fan base had grown over time. But the voice of these fans was contained to niche forums—their demands did not dominate the discourse about the game.

“In today's world, you have very active, opinionated fan bases on social media with expectations and questions about what you’re doing with their much-loved property,” says Curtis. “It just wasn't like that.”

Terror, isolation, and moments of emergent paranoia intermingle with more conventional action-horror gameplay in The Thing, a game that from a conceptual standpoint still feels thrillingly ahead of its time. There are few more affectionate tributes to the flawed, fascinating, and ambitious cult-classic game than the remastered version that was released last week, and the fact that Carpenter himself is a fan of it.

It’s perhaps a stretch to say that The Thing laid a blueprint for modern gaming adaptations of movie IP, but the creative pillars it rested on also support a raft of modern big-budget successors: a stand-alone story; an embrace of the interactive possibilities of the medium; a reverence for the source material. Those are precisely the qualities that Avatar stakeholders Disney and Lightstorm Entertainment thought Frontiers of Pandora should embody, explains Massive Entertainment creative director Magnus Jansén, via email. It was the IP owners’ and producers’ view that “to make a great licensed game you need to embrace the essence of the medium (interactivity, freedom, etc.), and you need to tell new stories with new characters in new locations.”

This philosophy began to gain steam in the mid-aughts, as game makers began to hone their adaptation craft just as filmmakers did with comic book IP. Nerd culture began to receive greater critical regard, and it also became a big business. In 2005, Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins showed that a superhero movie could attain an elevated aesthetic tone. In 2009, Batman: Arkham Asylum offered proof that a licensed video game could reach the same lofty level of quality.

Bryan Intihar, senior creative director of Insomniac’s acclaimed Marvel’s Spider-Man games, counts Arkham Asylum’s 2011 sequel, Batman: Arkham City, as an all-timer licensed title. “I think it really helped break the stigma [around licensed games],” he says, establishing “that you could make a ‘game of the year’ licensed title.” The Batman: Arkham games were validating for Intihar, because they demonstrated that if you “give these properties the proper respect, time, and talent, then you're going to be able to make something really memorable.” In 2018, Marvel’s Spider-Man was nominated for a slew of end-of-year awards, and it landed game of the year on Wired’s 2018 list. The magazine’s video game critic at the time, Julie Muncy, described it as a “title that adores its source material, that shapes its entire form around it.”

Intihar’s starting point on Marvel’s Spider-Man was modest: “Literally the first day, I said it’s not going to be an origin story, because those have been done to death.” He also stipulated that “[Spider-Man’s] webs have to attach to buildings.” From there, it was a case of homing in on the core “fantasy” of Spider-Man—swinging through Manhattan; quipping during street-level brawls—while tunnelling into the fundamental tension that has made the character so compelling for more than 60 years: Peter Parker’s struggles to do right in his regular life.

Intihar says the key component of a Spider-Man game is nailing the fundamental “duality” of the franchise’s storytelling: “Delivering a fantasy like the train fight [in Sam Raimi’s 2004 movie Spider-Man 2], and on the total flip side, making a scene between two basic talking heads feel as emotional and relatable as something in your favorite TV show.” In a video game, the latter is arguably just as hard as, if not harder than, the whiz-bang former.

For all the emphasis that the creators of licensed games inevitably place on the seamless nature of their collaborations with IP rights holders, the intensiveness of the work involved in these projects is significant. Jansén describes a “staggering” level of intercontinental communication concerning Frontiers of Pandora, because Avatar’s key creatives were in either Los Angeles or New Zealand and Massive is based in Malmö, Sweden. There was much to discuss: Jansén and his team devised an original story (which intersects with the events of the upcoming movie Avatar: Fire and Ash) while expanding the world of Pandora with emotive characters and new breeds of the captivating alien wildlife that’s such a calling card of Cameron’s environmentally themed, otherworldly opus.

Axel Torvenius, creative director of Indiana Jones and the Great Circle at MachineGames, admits there are “more things to consider” with a license holder such as Lucasfilm in the creative mix: “Making sure everything is signed off … something [might] need to be discussed, approved, and slightly adjusted,” he says. Torvenius took part in weekly meetings with representatives from Lucasfilm from the inception of the project. Pre-production was a painstaking process, as MachineGames fleshed out the story, incorporated feedback from Lucasfilm, and refined the vision. By modern triple-A studio standards, the Swedish outfit is a relatively lean operation, numbering just 162 employees, and a project of this nature placed significant strain on the studio. Torvenius describes the game’s production as “intense.”

Still, the results speak for themselves. Indiana Jones and the Great Circle is more than just a work of loving adaptation; it is a formally experimental first-person adventure that draws on the “immersive sim” elements of another Bethesda-published game franchise, Dishonored. MachineGames played with the swashbuckling tropes and heightened imagery that made the original movie trilogy such a hit, pushing what Torvenius describes as the films’ nearly “comic book” cinematography further than many would have dared. Think of The Great Circle as Old Hollywood meets New Hollywood meets genuinely bold triple-A game-making. The resulting experience feels familiar yet fresh, capturing the movies’ antiquated dustiness with cutting-edge rendering technology. Crucially, its focus on downing fascists also offers genuine skull-cracking catharsis. Like the Avatar game, The Great Circle does not pull its political punches.

For a new generation of fans, The Great Circle is the creative high point of a franchise that has, in recent years, waned in quality on the big screen. Does Torvenius feel the pressure of being a custodian for the Indiana Jones franchise? He rejects such a characterization. “I think we see ourselves more as a humble servant … that can carry a great legacy forward,” Torvenius says.

For Intihar, coordinating with Marvel Games has been part of his daily working life for a decade. He remembers when his boss, Insomniac cofounder and CEO Ted Price, gathered the whole studio in an auditorium on the Insomniac campus in Burbank, California, in 2014. Intihar knew the news that was coming because, at an earlier date, he had run into Price moments after the studio boss had stepped out of a meeting with Sony. As Price unveiled the Marvel logo behind him, Intihar remembers an “audible gasp” in the room. “That's a testament to Ted gauging the studio’s interest and going, ‘Hey, they seem really excited about this,’” Intihar says.

Now Intihar sends “five to seven” texts a day to Eric Monacelli, executive producer at Marvel Games, the division set up in 2009 to oversee the company’s interactive output. They talk “all the time,” he says, although the familiarity and trust took some time to develop. Intihar is proud of what their creative partnership has yielded—not just some of the most entertaining action games of the past two console generations, but a modernization of Spider-Man. Intihar recalls a line in 2018’s Marvel’s Spider-Man in which the idea of therapy is discussed. Monacelli looked at it as “an opportunity to show our audience that therapy is a good thing … He wasn’t looking at it from a Marvel standpoint. He was looking at it from a storytelling [perspective]—making a better, more powerful experience.”

“I know I’m painting a very rosy picture,” continues Intihar, “but I’ve had more disagreements internally than I have externally.” For Intihar, the relationship between Insomniac and Marvel is defined by a sense of taking things to the “next level” rather than getting bogged down in what many might assume would be a nearly endless paper trail of checks, balances, feedback, and sign-offs. This seemingly harmonious (and notably involved) relationship with Marvel—a far cry from the hands-off approach that defined licensed cash-ins of the aughts—has paid dividends not just in many millions of units sold, but also in the aggregate critical response. On Metacritic, Marvel's Spider-Man boasts a score of 87; Marvel’s Spider-Man: Miles Morales sits just below with a still-impressive 85; and Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 commands a remarkable average of 90.

In March 2024, Electronic Arts announced layoffs of about 670 workers, or five percent of its total global staff. Amid “accelerating industry transformation,” wrote CEO Andrew Wilson, the publishing behemoth was also “moving away from development of future licensed IP.” Greater focus, he continued, would enable EA to “double down” on its “biggest opportunities” including, he stressed, “our owned IP.”

A few years earlier, Japanese publishing giant Square Enix sold off Crystal Dynamics and Eidos-Montréal, the studios behind Marvel’s Avengers and Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy, respectively. Like the Warner Bros. Suicide Squad game, these gigantic licensed bets did not pay off financially. The same seems to be true of Ubisoft’s recent licensed efforts. In January, Frontiers of Pandora was reported to have made just $133 million in revenue, a figure that likely fell well below the game’s production and marketing budget. The sales projections for Star Wars Outlaws were lowered by J.P. Morgan not long after its release, from 7.5 million to 5.5 million. The game reportedly sold just 1 million copies in its first month.

Conventional wisdom might suggest that licensed games would represent safe investments, because the perceived bankability of known IP mitigates some of the risk associated with game development. But Gerstmann points to the unprecedented Insomniac hack, and the fees it appeared to reveal that Sony is paying Marvel for the Spider-Man license, as evidence that would contradict that theory.

“Because they’re having to give a bunch of money over to Marvel, they’re now having to sell even more copies of the game,” says Gerstmann. This is on top of the increasing cost of making and marketing triple-A games. Leaked budget figures for the Marvel’s Spider-Man series illustrate this trend. The first title, released in 2018 for PlayStation 4, is believed to have had a roughly $90 million price tag. The 2020 spinoff, Miles Morales, which was released simultaneously for PS4 and as a launch title for PlayStation 5, is said to have cost $156 million. 2023’s Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 is reckoned to have cost $315 million.

“The big-budget video game is at such a weird crossroads right now,” says Gerstmann. “I can see some of those deals being made with [mitigating risk] in mind. We’re seeing a lot of sequels, a lot of things that seem like safe bets. But they aren’t paying off either. I think studios are at a bit of a loss right now with how to proceed with games of this size.”

The investor, author, and essayist Matthew Ball paints a troubling picture. “Compared to a few years ago,” he writes in an email, “there are far fewer gamers, gamer hours, and gamer spend than nearly everyone anticipated. In fact, these measures have all declined.” Ball sees publishers going through a process of “re-evaluating” and “thinning” their production pipelines, doubling down on projects that might offer the greatest upside for success, “which tends to be their IP.” Ball contends that adapting another company’s IP comes with “substantial costs”—not just from a licensing fee that he says can range between 10 and 20 percent of net revenue, but because of the “incremental production costs that come from the time/rework required for various approvals (story, character, level, monetization, etc.).”

It might seem as if we’re in the midst of a glut of licensed video games, with some major titles set for release in the near-to-mid-term future: Arkane Lyon’s Blade; IO Interactive’s take on James Bond; Insomniac’s Wolverine; the final title in Respawn’s Star Wars Jedi series; a sequel to Hogwarts Legacy; upcoming Marvel and Star Wars games from Skydance New Media, a studio helmed by former Naughty Dog creative director Amy Hennig; Alien: Rogue Incursion, an attempt to follow in the (quiet, tentative) footsteps of revered (and influential) 2014 survival horror classic Alien: Isolation; a Monolith Productions Wonder Woman game (maybe).

However, it appears that some companies are actually in the process of shifting resources away from such projects. That dissonance is the product of the long lag time between a game getting greenlit and announced, and its actually coming out on consoles and PCs. Ubisoft unveiled Frontiers of Pandora in 2017, six years before its eventual release in December 2023. The industry’s pivot to subscription services like Game Pass, should it continue, could also cause licensed titles to get scarcer: Xbox CEO Phil Spencer recently expressed apprehension about greenlighting licensed games because of the risk of delisting from said services when their licenses expire.

If licensed blockbusters turn into an endangered species, then a wave of indie operations are positioning themselves to cater to legions of bereft fans. Indie publishing powerhouse Devolver launched its own sublabel, Big Fan Games, in October, dedicated solely to publishing licensed titles. Amanda Kruse is the head of its business development: She got her break in television and film before helping establish the video game division at Lionsgate. Kruse knows what it takes to turn up all manner of licenses, from “weird esoteric films that had a limited release in the 1930s” to Chuck Russell’s 1988 cult horror classic The Blob. Tracking down licenses and liaising with the licensors is an express part of Big Fan’s pitch to developers. Partners such as Disney (which Big Fan is working with on upcoming isometric action-adventure game TRON: Catalyst) are also pitching Big Fan, because they’re keen to put their expansive libraries of IP to work. “They're super into it,” says Kruse.

Xalavier Nelson Jr., creative director at Strange Scaffold, strikes a further note of caution against the widespread push towards licensed games (despite having just announced Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Tactical Takedown). The creative director of offbeat indie successes like this year’s Clickolding believes video games still command an audience that is willing to risk its time with an unknown entity simply because it “looks cool.” His worry is that if companies invest in licensed-game comfort food to a greater degree than their own original IP, players may forget how to take risks with their purchases. “If we erode that ability,” he says, “we may never get it back.”

Perhaps the name of Kruse’s label, Big Fan Games, is emblematic of this internet-age dilemma. These licensed games are an expression of a societal embrace of fandom at every level, from players to programmers, creative directors to C-suite executives. It helps that a demographic shift has occurred, according to Kruse: Decision makers at movie studios are increasingly “elder millennials” who can move “fluidly” between video games and movies. That’s part of the reason why, as licensed video games have improved in quality, the same has happened with movie and TV adaptations of video game properties, like The Last of Us and Fallout. “There is not a burden of education, they just organically get both,” Kruse says of these gaming-literate execs.

Intihar has now worked on Marvel’s Spider-Man games for the past 10 years. If leaked Insomniac slides are accurate, Intihar and his coworkers at Insomniac are signed up for at least an additional six years of Marvel games, and the studio’s next wholly new IP isn’t scheduled to arrive until 2031. This situation suits Intihar just fine. “I love all superheroes. I love working on these games. I love working on these properties,” he says. “I would do it forever if I could.”