In a year when at least three conversation-piece releases featured sequences involving visionary architects outlining their grand plans for the future (The Brutalist, Megalopolis, and Wicked), the question of form and function loomed large: Does one follow the other, vice versa, or not at all? Beautiful compositions can be superfluous, throwaway inserts can be essential, and elaborate tracking shots can lead to nowhere (or, if you work for Alfonso Cuarón or Alejandro González Iñárritu, straight to the awards podium). As always when compiling this list, I’ve tried to give a sense of variety in the ways that filmmakers and cinematographers can distill meaning, emotion, and mystery into camera placement, movement, and color. As social media becomes increasingly screenshot happy, it’s worth thinking about the dangers of proffering individual frames as evidence of mastery, but it will also hopefully lead readers to check out the movies these fleeting glimpses are attached to—to let the part lead them toward the whole.

The Brutalist (Directed by Brady Corbet, Cinematography by Lol Crawley)

The curtain-raiser of Brady Corbet’s immigrant epic nods to The Godfather Part II (and also maybe Planet of the Apes). For Adrien Brody’s travel-weary Hungarian émigré, America and its coastal sentinel have the appearance of a world turned upside down. The Brutalist is explicitly a movie about iconography—about building things up and breaking them down—and Corbet’s polyvalent use of the Statue of Liberty deserves props for imagination and engineering. Viewed through a lurching, seasick lens that aligns our point of view with the protagonist’s, Lady Liberty appears simultaneously as a creative muse, a beacon of freedom, and a siren potentially luring our hero to shipwreck—or maybe a gigantic statuette for a director and his cinematographer to add to their mantelpieces.

Deadpool & Wolverine (Directed by Shawn Levy, Cinematography by George Richmond)

To clarify: Deadpool & Wolverine is mostly an ugly-looking movie devoid of the kind of visual imagination on display in other 2024 blockbusters like Dune: Part 2 and Furiosa, both of which make desert landscapes beautiful and immersive. But to paraphrase a much better comic book franchise, these aren’t the images we need, but the images we deserve, and Deadpool & Wolverine’s smug procession of industry in-jokes feels like Hollywood’s reckoning. Of course, it’s supposedly all in good fun that Levy’s film stages a victory lap for the MCU around its own ever-expanding intellectual properties, and that this guided tour involves having our hero pose amid the ruins of the 20th Century Fox logo—a moment no less monumental than the aforementioned shot from The Brutalist. The point, such as it is, has to do with one of the great American studios being reduced to a half-buried sight gag in a competitor’s unstoppable conglomeration, and it lands like a semiotic sucker punch—one vicious enough that you wish the filmmakers didn’t hedge by shelling out for Green Day over an end credits montage celebrating Fox’s Marvel-branded output. No less an industry bible than Variety called the coda a “shockingly sweet eulogy” for summer blockbusters past, but in the context of a film that’s the cinematic equivalent of a shit-eating grin (Ryan Renolds’s specialty these days), the deluge is made up entirely of crocodile tears.

Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World (Directed by Radu Jude, Cinematography by Marius Panduru)

Forget A Complete Unknown: The best Bob Dylan homage in any movie this year comes near the end of Jude’s extraordinary tar-black comedy Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World, which knowingly evokes—and travesties—the memory of the pioneering music video for “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” The man holding the cue cards has been selected to star in a PSA about job safety subsidized by the company under whose employment he injured himself; instead of letting their wheelchair-bound star say his piece—or even parrot the lines being fed to him by the director—the producers tell him to hold up green cue cards where the correct statement can be added in post. At nearly 40 minutes in length, Jude’s coda is like a self-contained short film—one where the camera never moves, cuts, or blinks. Instead, it holds its gaze while a victim is instrumentalized into a late-capitalist mouthpiece while surrounded by his increasingly impatient and bewildered family—props in a diabolical photo op whose static, distanced style hearkens back to the origins of cinema while diagnosing and distilling 21st-century malaise.

Here (Directed by Robert Zemeckis, Cinematography by Don Burgess)

Technically, Here qualifies as a single 104-minute shot, albeit one subject to endless physical and digital manipulations (a behind-the-scenes documentary on its production would be a thriller). The contents of the frame keep changing—and subdividing—even as the camera remains still; the carefully blocked movements of the actors compete for our attention with the shifting positions of various props and ever-mutating gradations of fashion and decor. That many of Here’s spectacularly multifaceted compositions are taken directly from Richard McGuire’s graphic novel doesn’t diminish their inventiveness; in a true conceptual coup, Zemeckis has two characters in one timeline drag a mirror into the line of sight, which ends up reflecting—and revealing—their home’s heretofore unseen kitchen and dining room table, as well as serving as a proscenium for two similarly fraught family meetings occurring several decades apart in time and side by side in space. The sheer complexity of Here’s visual scheme is such that it’s hard to take in on a single viewing. The strangely anodyne nature of its storytelling and CGI-assisted performances, meanwhile, may also keep people from coming back for a second look. For those inclined to analyze Zemeckis’s stylized mise-en-scène—to pore over its intricate latticework of planes and angles—Here could become a source of obsession.

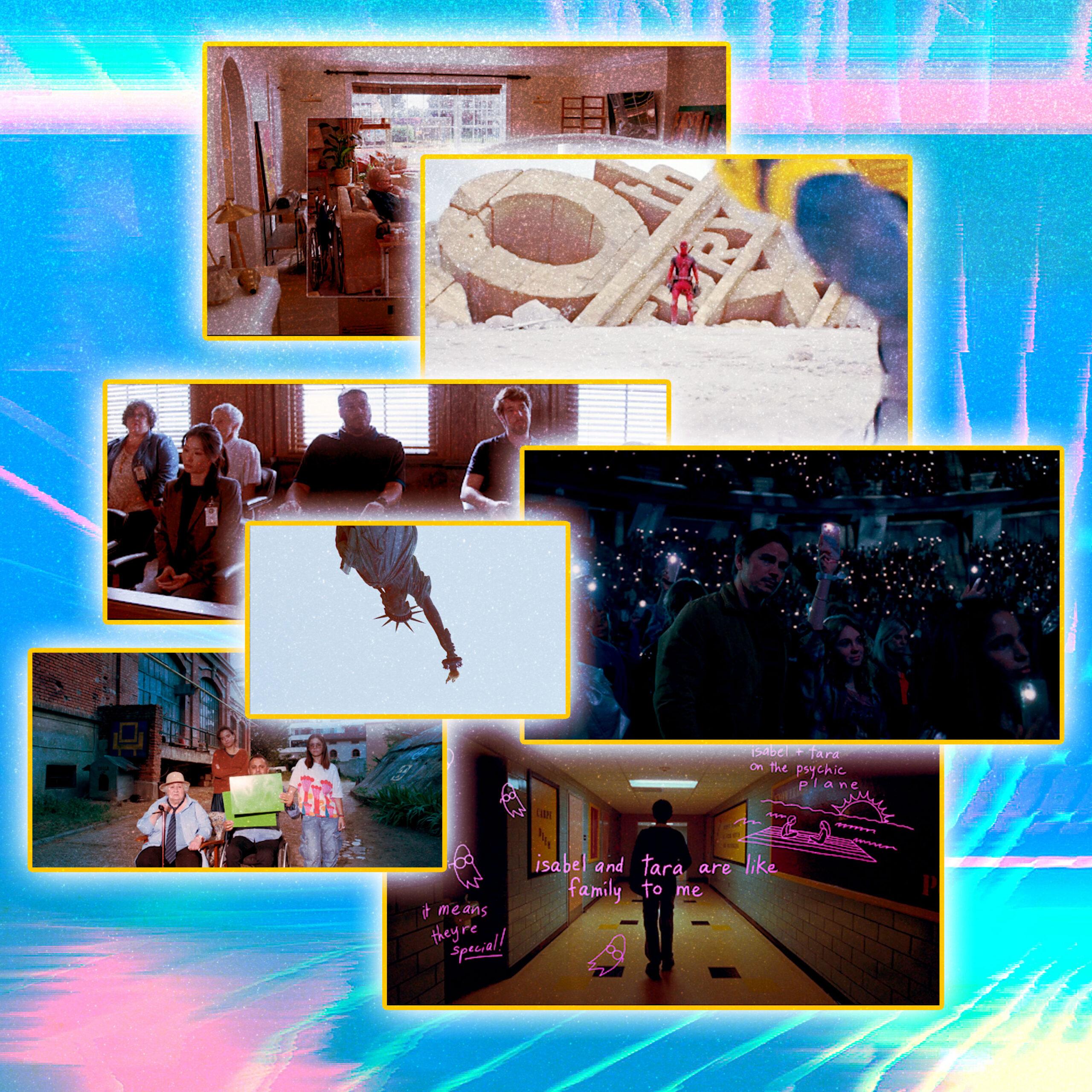

I Saw the TV Glow (Directed by Jane Schoenbrun, Cinematography by Eric Yue)

The writing is on the wall, and also on the screen: The centerpiece sequence of Schoenbrun’s melancholic and hauntological I Saw the TV Glow subsumes influences from Jean-Luc Godard to Gus Van Sant to the David Fincher of Zodiac while sketching out an original vision of adolescent exile. Stalking through the halls of his high school en route to retrieve a precious VHS that’s been stashed away by his best pal, Maddy, Justice Smith’s Owen is surrounded by superimpositions of her notebook scribbles; the warm, neon hues of her writing illuminate their shared obsession with a YA TV show called The Pink Opaque. Meanwhile, the official school signage on either side of the frame completes the semiotic puzzle—seize-the-day platitudes relegated to Owen’s peripheral vision, where he may not notice them until it’s too late. The use of Caroline Polachek’s gorgeous, grungy song “Starburned and Unkissed”—a track about ardent, ephemeral desire, manifested in whistling kettles and dangling phantom limbs—blasts Schoenbrun’s filmmaking into the stratosphere.

Juror No. 2 (Directed by Clint Eastwood, Cinematography by Yves Belanger)

Your honor, let the record show that Eastwood is historically one of the most self-aware American filmmakers of all time, consistently and compulsively reflecting on and revising his legacy as both an action star and auteur. Sometimes, it’s easy to see the mirroring between Eastwood’s life and work because he’s right there on the screen, squinting into the middle distance. Sometimes, though, he asserts his presence in more abstract ways: I submit into evidence this crucial—and spoiler-free!—composition from Juror No. 2, which cannot help but call to mind Eastwood’s bizarre chair-addressing performance at the 2012 Republican National Convention, which had plenty of people writing him off on ideological grounds as well as ageist ones. Leaving aside the fact that the 94-year old Eastwood would seem to have his shit together more than a number of present or future American political figureheads, the focus on an empty chair in a movie deconstructing the challenge (and necessity) of personal accountability demands commentary; not only does it work on multiple levels as a plot point and a personal reckoning, but it also collapses the distance between them. For people who think great directing consists solely of showy camera moves, Eastwood’s plain mise-en-scène can seem drab or underwhelming—a by-product of always shooting quickly, with the finish line in sight. Simplicity isn’t so simple, though, and like the movie it’s attached to, this shot gets more beautiful and stark and troubling the more you turn it over in your mind.

Nickel Boys (Directed by RaMell Ross, Cinematography by Jomo Fray)

Here’s looking at you, kids: The dual-point-of-view gambit of Ross’s feature fiction filmmaking debut unfolds as a balancing act between technique and emotion, and the moment when the eyelines of the characters played by Ethan Herisse and Brandon Wilson converge provides something that no other movie this year can claim. It’s an image we haven’t quite seen before: a gaze that looks in two directions at once, through two different sets of eyes, hovering detachment and street-level humility in the same instant. Isolating this frame from the sophisticated slipstream of Nickel Boys’ visual storytelling arguably does Ross and his cinematographer Jomo Fray a disservice, but this is also supposed to be a frozen moment—something both boys will remember as long as they live, in exactly the same way. By the end of the film, the sense of mutual wonder and recognition on display will be reconfigured, but not broken—the beauty of the shot is indestructible.

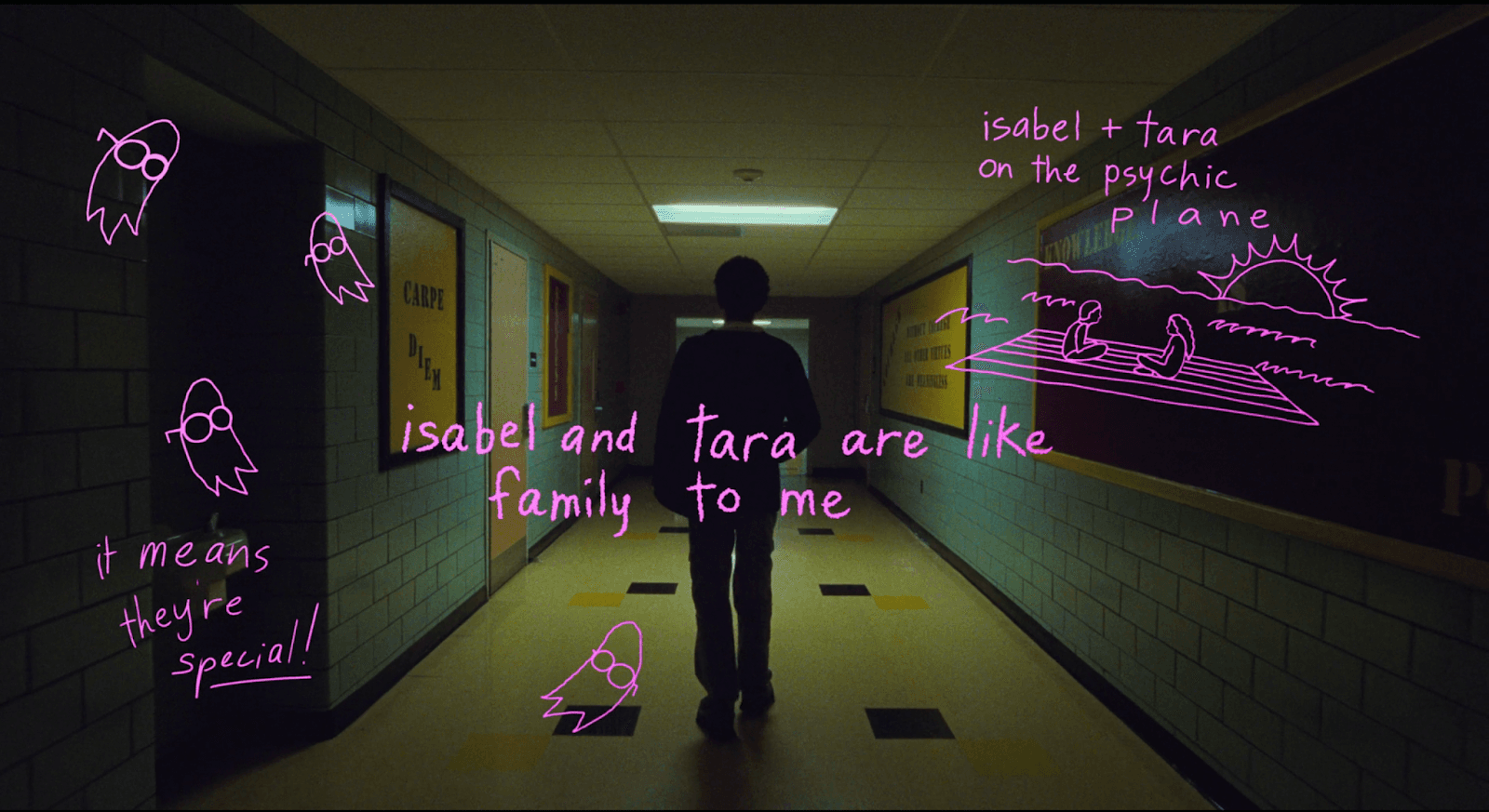

Last Summer (Directed by Catherine Breillat, Cinematography by Jeanne Lapoirie)

Each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Sipping coffee on the porch of their well-appointed home, Anne (Léa Drucker) and her husband, Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin), don’t notice the latter’s teenaged son, Théo (Samuel Kircher), hovering behind them like a ghost. Catherine Breillat’s movie takes the form of a jagged, semi-incestuous love triangle, with Théo recklessly seducing his stepmother only to run crying into his dad’s arms when things go awry—at which point loyalties start getting tested in every direction. Breillat isn’t a flashy director, but she’s been pushing buttons and prodding sensitive spots for the better part of 50 years now, and she wields her camera setups with surgical precision; the killer detail in this shot is the way that the glass door renders Kircher’s character ephemeral—as a reflection of the adults’ subconscious anxieties about themselves and each other. The filmmaking in Last Summer feels effortless at all times, which doesn’t make watching its emotional atrocity exhibition any easier.

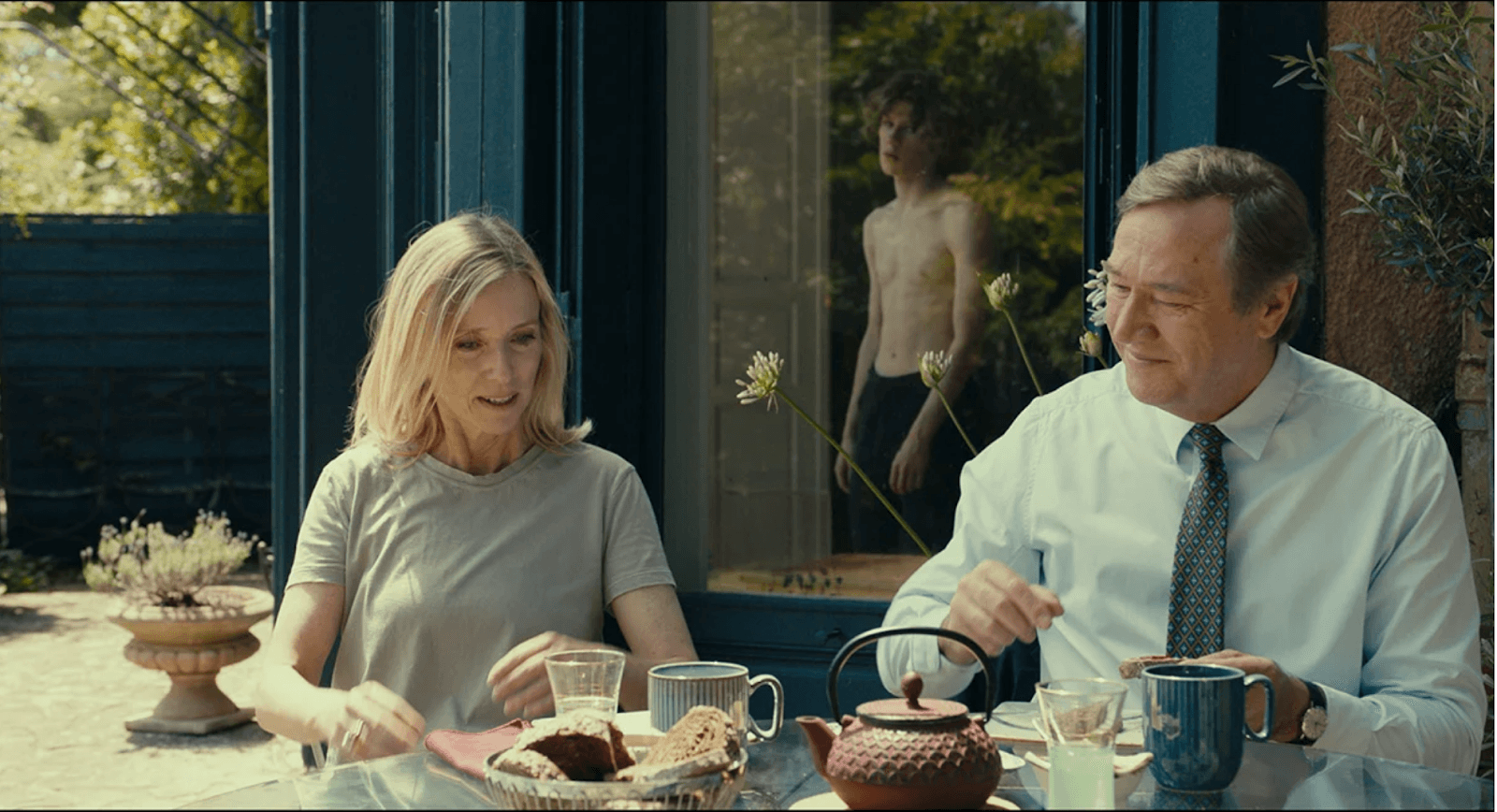

Red Rooms (Directed by Pascal Plante, Cinematography by Vincent Biron)

There’s an art to taking a great selfie—ideally, it involves cosplaying as a complete stranger with a tragic backstory. For extra cred, sneak into that person’s bedroom in the middle of the night, in the dark, and make sure to use the flash on the brightest setting. While not technically a horror movie, Red Rooms features several of the year’s weirdest, freakiest, most watch-through-your-fingers compositions; in addition to being a superbly inscrutable character study, Plante’s movie is savvy about image making in general. Consider that Juliette Gariépy’s character makes a living as a model—the subject of a probing and commodified professional gaze—and that her journey toward self-actualization (via a series of bizarre choices not worth spoiling here) involves capturing and uploading her own image in a moment that’s genuinely horrifying and suddenly gives even more context to unpack. It’s a Pandora’s box containing ideas and feelings that most viewers would probably rather keep tightly packed away.

Trap (Directed by M. Night Shyamalan, Cinematography by Sayombhu Mukdeeprom)

Like any good pop demagogue worth her entourage, Lady Raven preaches the purifying powers of forgiveness: Staring out at her throngs of adoring fans, she tells them to turn their flashlights on and imagine somebody who’s hurt them, and then to imagine telling the guilty party that it’s all OK. Now notice that this man—Cooper Adams, the lank-haired hulk in flannel played by Josh Hartnett—did not have his hands up. Being a serial murderer, Cooper has plenty to apologize for, but at this point in Trap, he’s preoccupied with memories of the woman whom he believes shaped him into a monster—his mother, of course. He won’t be forgiving her anytime soon, and for all its goofy expositional flourishes, Trap is locked into the loneliness of its protagonist, whose preternatural skills at blending in grow increasingly strained as he tries to balance his instincts as a butcher against his responsibilities as a father. The superbly color-coded cinematography by Sayombhu Mukdeeprom drenches Cooper’s alienation in cool blue hues illuminated by a thousand points of light—a prelude to a key moment involving a cellphone as a source of salvation.

Union (Directed by Brett Story and Stephen Maing, Cinematography by Stephen Maing, Martin Dicicco, et. al)

Full disclosure: Brett Story, the codirector of Union, is a colleague of mine at the University of Toronto; hopefully, saying that this is one of my favorite cinematic images of the year doesn’t seem like favoritism. Union’s chronicle of the grassroots worker campaign coalescing around an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island combines journalism and polemicism in powerful ways; the fact that the scenes depicting employees being fed corporate union-busting rhetoric via video were filmed surreptitiously with cellphones gives the footage the charge of a paranoid surveillance thriller. The best documentaries are the ones that question and challenge power, and Union punches up in sync with its subjects.