When you grow up as a baseball fan, you know the best player born on your birthday. Sharing a birthday with a famous player is a point of pride: You can convince yourself that some measure of their glory reflects on you, or that you too might be bound for great things. I used to feel lucky to be born when I was, instead of on some inauspicious, mundane date like January 25 (career WAR leader: 19th-century pitcher Danny Richardson), February 14 (Pretzels Getzien), or December 3 (Wayne Garrett). If I’d debuted hours earlier, I would’ve been stuck with December 24 (Kevin Millwood now, maybe William Contreras someday, but when I was young … Zeke Wilson?). Instead, I was born on Christmas morning, which made my friends joke about how I had the same birthday as Jesus. But Jesus wasn’t truly born on December 25, and he was just alright. Rickey Henderson was a Christmas baby to brag about. And like Henderson himself, I happily did.

When I blow out my birthday-cake candles this Christmas, it will mark the first time I can’t take pleasure in thinking that somewhere, Rickey might also be blowing out his. Henderson, who burned as bright as any athlete, has himself been snuffed out: He died on Friday, reportedly of pneumonia, a few days short of turning 66.

On the field, Henderson had exquisite timing; in life, a little less so. He left the scene too soon, after arriving before baseball was ready for him. Had he come along today, he might have been embraced more warmly than he was in his day. Then again, baseball wouldn’t look like it does now if Rickey hadn’t refashioned the sport in his image. He turned his day into today.

Henderson’s “day” is difficult to identify, because his athletic longevity is legendary. He turned 28 the day I was born, yet he hung on so long that by the time he played his last professional game, for the 2005 San Diego Surf Dawgs of the upstart Golden Baseball League, I was just starting college. He was caught speeding during his days as a Surf Dawg, but rarely caught stealing; he nabbed 16 bags in 18 tries in his swan song, against independent leaguers who were, on average, 20 years younger. Rickey resisted retirement so successfully—and also unsuccessfully, for several years after teams decided he was done—that on some level, I assumed he’d hold off interment for a long time too. “I just don’t know if Rickey can stop,” Henderson told The New Yorker’s David Grann in 2005. Now we know, and I wish we didn’t.

In a statement about Henderson’s passing, MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said, “Rickey earned universal respect, admiration and awe from sports fans,” which would have been news to Rickey. In 1999, millions of baseball fans voted on MLB’s All-Century Team. The evidence that Henderson deserved to be selected was right in front of fans’ faces: He had claimed his record 12th stolen base title in 1998, and he still had plenty left in ’99, when at age 40 he hit .315/.423/.466 in 121 games for the Mets, with 37 steals. Yet Rickey ranked 17th among outfielders in the All-Century voting, well behind his former teammate Tony Gwynn—a great player, but not in Rickey’s class. Pre-Moneyball batting average fixation probably played a part in that placement, but so did Rickey’s reputation. “Rickey has been baseball’s most notorious hot dog for two decades,” ESPN’s Jim Caple wrote in 2001, noting that Henderson’s ego and perceived lack of effort had “alienated fans.” Caple reported Rickey’s take on himself and 18th-ranked Barry Bonds: “We never got our due and we’re never going to get our due until it’s all over with.”

It is, sadly, all over with now, so let’s give him his overdue due. Henderson’s baseball hero was Willie Mays, whose no. 24 he wore for all but the last two of the nine MLB teams he played for. When Willie—another all-timer with whom every baseball fan has been on a first-name basis—died in June, conversation turned to his successor as the game’s greatest living player. Bonds, Roger Clemens, and Alex Rodriguez had the strongest statistical cases, but they’d each incurred a degree of disgrace. Which left only one choice in the “believed to be clean” category: Rickey Henderson. (“My God, could you imagine Rickey on ’roids?” Henderson said in 2005. “Oh, baby, look out!”) It’s a pity that he held that distinction for only six months.

Henderson is most famous for violating the Eighth Commandment more often than any other player: His record of 1,406 stolen bases will remain almost as unbreakable as Cy Young’s 511 wins, no matter how many rules MLB tweaks to make it easier to steal. Henderson stole a record 130 bags in 1982, prompting Tom Boswell to marvel that Rickey was “challenging the basic dimensions of the diamond.” The distance between Henderson and second-ranked Lou Brock on the all-time stolen-base leaderboard is as wide as the gulf between Brock and Jimmy Rollins in 46th place.

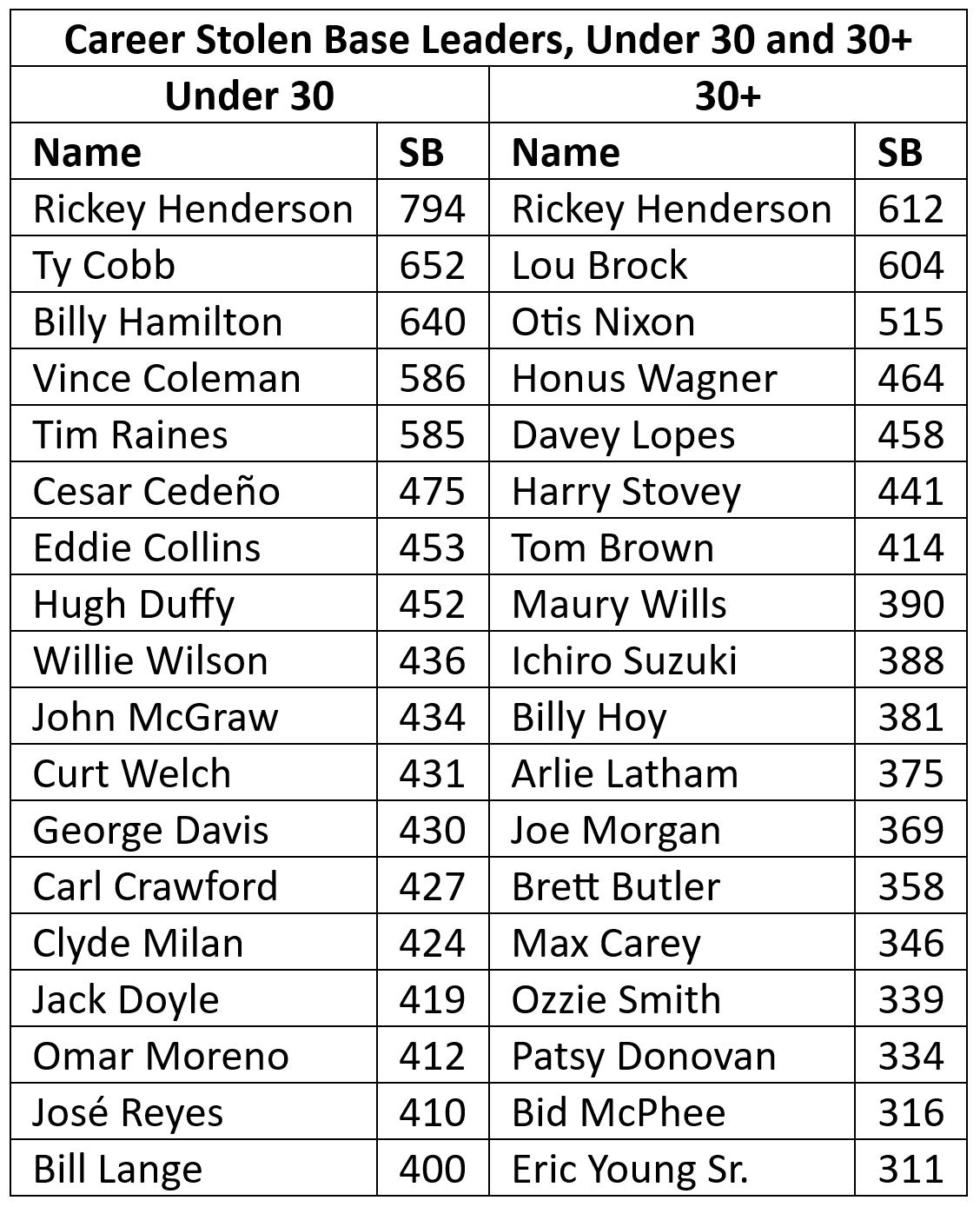

That’s not the most impressive stat about Henderson’s steals. Try this table on for size: The players on the left are the all-time stolen-base leaders through age 29; the players on the right are the all-time leaders from age 30 on.

Notice anything? Other than Henderson, who leads both lists, no other player appears on both leaderboards. You’d have to go down to no. 19 on the under-30 list (Max Carey) or no. 21 on the 30-and-over list (John Ward) to find other repeat appearances. Most prolific base stealers either burst out of the starting gate fast and then slow down dramatically, possibly because of the wear and tear that comes with so much sliding, or bloom late, because it takes time for them to refine their on-base ability or sliding technique. (Ichiro wouldn’t qualify for the under-30 list even if we counted his swipes in Japan.) And then there’s the Man of Steal, unmatched in both age groups. After Maury Wills stole 104 bases in 1962, he said, “I don’t see how I can ever come close again. The physical beating I took is more than I want to endure.” Rickey reached 100 three times in four years.

Relatedly, Rickey scored more runs than anyone else, achieving an offensive player’s primary objective 2,295 times. Much of his scoring was self-sufficient, supplied by his power or a manufactured (literal) run. The self-described “creator of chaos” also broke Babe Ruth’s record for career walks, and though his tally was soon surpassed by a PED-powered, game-breaking Bonds, Henderson still holds the record for unintentional walks. Thanks to those free passes, he finished with a .401 on-base percentage, after 25 years in the majors (or .409, across all professional levels over 30 years). I recently started using a laptop with a larger screen than my old one, which is fortunate now: If I futz with the scroll bar until the Baseball-Reference table is perfectly positioned, I can just see all of Henderson’s seasonal stats at once, with a few pixels to spare.

Even if you can cram those seasonal lines onto a single, unscrolled screen, you might miss the forest for the OBPs. Henderson seems even more amazing when we compare him to other elite talents—or when we focus on the components of his stardom. In his entry for Rickey in the 2001 New Historical Abstract, Bill James wrote, “If you could split him in two, you’d have two Hall of Famers.” Which, aside from the anatomical drawbacks of being bisected, is entirely true. Of the 172 non-Henderson Hall of Famer hitters who didn’t play predominantly in the Negro Leagues, the median member produced 61.8 WAR, roughly six more WAR than half of Henderson’s total. Split his 111.1 in two, and each half-a-Henderson’s worth of WAR would be enough to equal or exceed the sums of 72 whole Hall of Famers.

Another way to express Henderson’s overqualification for Cooperstown is to perform another piece of statistical surgery and subtract his greatest claim to fame: the steals. The havoc Henderson wrought on the bases was his greatest contribution to baseball lore, but not to his teams’ success. For proof of that, look no further than his work in the batter’s box, which may have seemed like the warm-up act for the real Rickey show but was really the main event. As Henderson said in 2013, “People ask, ‘How do you steal all those bases?’ But they never say, ‘What do you do to get on base?’”

Rickey was an offensive force before he stepped foot on the basepaths. From Henderson’s first full season through the end of his prime—let’s draw that line after 1993, his age-34 season—he was the fifth-best hitter in baseball, posting a 145 wRC+ surpassed only by Frank Thomas, Mike Schmidt, Bonds, and Fred McGriff. His performance at the plate alone would have made him a Hall of Famer: Rickey ranks 32nd in career batting runs (which are separate from baserunning runs). Only seven players who topped his total aren’t in the Hall, and they’re all either not yet eligible (Albert Pujols, Mike Trout, Miguel Cabrera) or excluded because of ties to PEDs (Bonds, Manny Ramirez, Rodriguez, Gary Sheffield). And it’s quite conceivable that Rickey, the rare natural lefty who hit righty, would have been better had he batted from the left side and enjoyed the platoon edge more often. (His OPS against righties was 74 points lower than his OPS against lefties, and he faced righties more than twice as often.)

Rickey’s walks (which far outstripped his strikeouts) were the foundation of his offensive attack, but he was hardly a slap hitter. Henderson ranks second behind Bonds in career power-speed number, a James creation that credits players for how many homers they hit and bases they stole, as well as the balance between those two sums. Rickey’s steals did a lot of the lifting in his power-speed rank, but hitting 297 homers helped. During that prime period from 1980 through 1993, only 31 players out-homered Henderson—and fewer would have done so had he not played most of his games for the A’s, whose home park was a lousy place to go yard. One of the few statistical goals Rickey couldn’t quite fulfill was reaching 300 homers, but he would’ve cleared that threshold easily had he hit in more favorable offensive environments. All in all, he homered 27 more times on the road than he did at home.

That Rickey worked his way on as often as he did, even though pitchers knew that to walk him was often tantamount to giving him second or third, was a testament to his eye. But it was also a byproduct of his power. Without that capacity to wallop mistakes, pitchers would have challenged him more, and he wouldn’t have walked as much no matter how minuscule his strike zone. All of his weapons worked in concert to ruin defenders’ days: The power forced pitchers to nibble; the eye gave him the discipline to let balls go by; and once he was on base, the instincts and speed went to work.

We’re still discussing stats, and numbers alone can’t capture the totality of Rickey: The way he modeled his headfirst slides after an airplane landing; the resulting rescue of his uniform from its pristine, unnatural state; the crouch that made his strike zone “smaller than Hitler’s heart”; batting gloves that put the green of the grass (or turf) to shame; his patented snatch catch; his compact, powerful frame; his hometown-hero status in Oakland; the frequent references to himself in the third person; and the countless stories about Rickey’s quirks, all too amusing to be true, though a few of them were anyway.

A player with such a distinctive style, and with such a standout tool, should’ve been ripe for overrating, if anything. (Stolen bases are flashier than they are valuable, and Rickey got caught stealing a record 335 times—albeit less often over time.) Yet Rickey was too great for even Rickey to overrate. Among most observers, he was underrated, and exclusion from the All-Century Team wasn’t the only evidence. He made 10 All-Star Games, not a lot for a guy who played 25 seasons and had 14 campaigns of more than 4.5 WAR. Bonds was the only hitter who compiled more WAR than Rickey over that quarter century, but nine hitters made more All-Star teams. (Cal Ripken Jr. made 19 Midsummer Classics, including several when he was well past his prime; Gwynn, less valuable than Rickey or Cal, was an All-Star 15 times.)

Rickey led American League left fielders in fielding runs five times, and AL center fielders once, and won one Gold Glove. He also won one MVP award, in 1990, which seems stingy for a player who had four seasons of more than 8.5 WAR. In 1980, he trailed only George Brett in AL WAR, but finished 10th in MVP voting; in 1985, he led the AL in WAR, and finished third; in 1989, he led all AL position players, and finished ninth. And it’s not as if he never played for good teams; he made the playoffs five times in his prime and eight times in total, won two championships (not counting a 2005 title with the Surf Dawgs), and hit better in October overall than he did during the regular season.

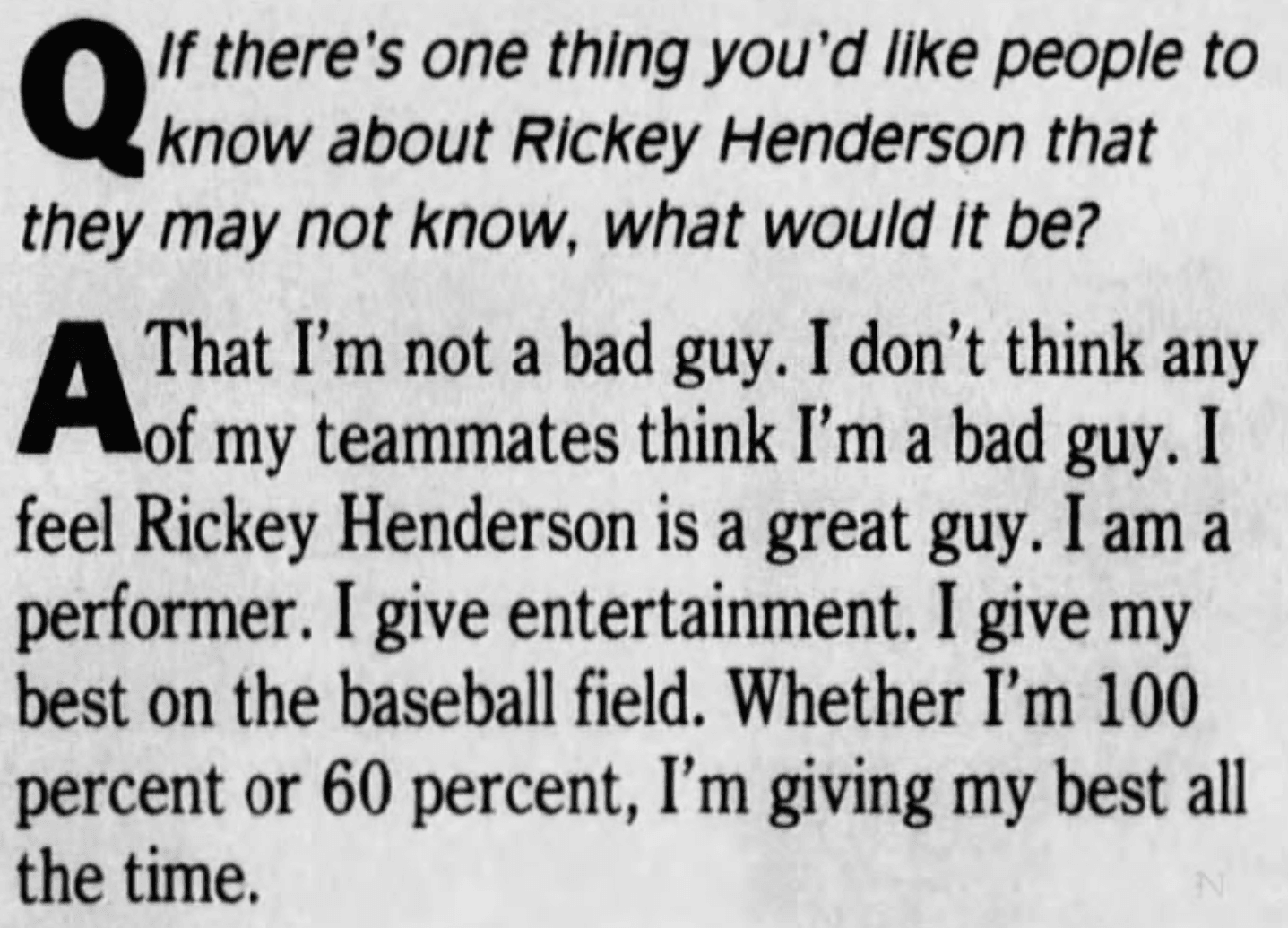

Granted, no one was looking at WAR in the ’80s and ’90s, and few people were paying attention to walks. (Moneyball came out during Rickey’s last big league season, and the following year, OBP became a better predictor than batting average of whether a player would return to his team.) But Rickey rubbed the public, the media, and sometimes his managers or teammates the wrong way. Sometimes, signals seemed to get crossed. Declaring himself “the greatest of all time” when he broke Brock’s record was one such occasion. Never mind that Rickey was specifically calling himself the greatest base stealer of all time, which seems indisputable. Or that before he praised himself, he thanked God, the fans, and his mother, among others, and credited Brock with being “the symbol of great base stealing.” His matter-of-fact pronouncement was still seen as the height of hubris. Few saw through the swagger to what his wife remembered as a “humble soul.”

Even more confounding, Henderson was dogged by doubts about his desire, which seems preposterous considering how hard he clung to the game when it wanted to be done with him. You could call that ego also: On some level, he couldn’t accept that his skills had slipped. But consider the absurdity of accusing a player who ranks fourth in games and plate appearances—and who would’ve kept climbing those lists if anyone would’ve let him—of not trying to stay in the lineup. “Sometimes when I sit around and look at the game and things [aren’t] going right, I just think, ‘Just let me put on the uniform and go out there and take a chance,’” he said in 2011. “I think that’s just because I love the game so much.”

Some combination of racism, resentment of his high salaries, and how easy he made the game look cost him popularity, if not notoriety. But in retrospect, his career controversies didn’t amount to much. The résumés of so many baseball icons who played before, during, or after Rickey’s career are littered with black marks: domestic violence incidents; DUIs; multifarious forms of cheating. Contrast those infractions with Rickey’s … tendency to talk a big game? The “personal life” section of his Wikipedia page, where one now expects to see a litany of misdeeds, contains two sentences that don’t pertain to his death: one about how he married his high-school sweetheart, and one about how they had three kids.

Let’s face facts: Football was Rickey’s first love, and given the NFL’s ascendance and MLB’s dwindling African American player base, a 2020s Rickey would probably gravitate toward the gridiron. But if this reincarnated Rickey were to stay on the diamond, he’d probably be beloved. Today, his self-aggrandizement and home run pimping would widely be seen as sincere, entertaining displays of emotion; his days off would be viewed through the lens of load management; his holdouts would be hailed by a more pro-labor fan base and baseball media; his holistic value would be quantified and acclaimed; and his small acts of kindness would gain greater visibility. See the viral response whenever someone invokes the unforgettable “Full share!” story from Mike Piazza’s autobiography.

No team today would let Rickey run like he did in the ’80s, but in other ways, he would fit right in. His record 81 homers to lead off a game presaged a leaguewide shift toward greater power and production from the leadoff spot, historically the realm of speedsters with meager pop. Maybe George Springer, Mookie Betts, Kyle Schwarber, or Ronald Acuña Jr., will topple that Rickey record, but whoever hits that 82nd airborne will be paying tribute to Henderson, consciously or not. Rickey will remain the best-ever leadoff batter, because all subsequent leadoff men have followed in his footsteps and struggled to keep up. Rickey was hyperbole-proof: By breaking records, he broke the mold.

Baseball has plenty of power, but Rickey’s other attributes have been in shorter supply. And with due deference to Tim Raines, Vince Coleman, and Willie Wilson, Rickey is the archetype of the high-contact, high-speed product MLB is trying to re-create. “When we considered new rules for the game in recent years, we had the era of Rickey Henderson in mind,” Manfred’s statement said. In an MLB promo last spring, Bryan Cranston intoned, “Field like Ozzie; run like Rickey.” Easier said than run.

“I wish the game would be just left alone,” Henderson said in response to the new rules. “But if they’re going to [make these changes] they got to add 50 or 60 on mine. That’s the new rule.” No one was sure whether he meant 50 or 60 steals total or per season, but knowing Rickey, it was likely the latter.

Cruelly, Oakland fans have in quick succession lost both Rickey Henderson and A’s games at Rickey Henderson Field, where Rickey was last seen standing—as usual, looking like he hadn’t strayed far from his playing weight—in late October. “I’m just happy to be here for this opportunity to be on this field for the last time,” said Henderson, who had never wanted to leave. No rule changes will produce a perfect copy of Rickey, and now the original is lost. But he left us lots of highlights, and I imagine he would want us to watch them and think, “Shit, that guy was good.”

“To steal a base, you need to think you’re invincible,” Henderson said. Rickey clearly convinced himself that he was—and until Friday, he had us fooled, too.