The only truly universal experience among Star Wars fans isn’t scorning The Rise of Skywalker or bemoaning The Book of Boba Fett. It’s pretending to use the Force. Maybe you’ve imagined a well-timed Jedi mind trick to get out of trouble; maybe you’ve daydreamed about floating the TV remote from a distant table to your hand so you don’t have to get off the couch; maybe you’ve yearned to use Luke’s fancy Force projection technique to look like you’re at the office while working from home. Even experienced Star Wars actors—the people most keenly aware that the Force is fiction—can’t resist maintaining the illusion off set. “I always do a little Jedi move for the doors,” Ewan McGregor confessed a few years ago, describing his routine on the way in and out of the supermarket. He continued, “Occasionally I’ve been caught doing that, and that’s kind of embarrassing. It’s difficult not to, isn’t it?”

Refrain from futilely trying to harness the energy field that supposedly surrounds us and penetrates us? That’s impossible! Sure, it might be a bit embarrassing to be spotted stretching one’s hand toward an unreachable object, but it’s also extremely relatable. Most of us never come closer to manifesting Force powers than when we wave or clap to turn lights on or off, yet we can’t help but make the attempt.

Think about this, though: In the Star Wars galaxy, the Force is not a bunch of mumbo jumbo—it’s all true. In a world where the Force is real and technology is sufficiently advanced to be indistinguishable from magic, wouldn’t people pretend to be Jedi all the time? Whether just for fun or because—if the Force doesn’t defy physics—they could, with the right props, plausibly pass themselves off as mystical superheroes?

Skeleton Crew, the latest Star Wars series on Disney+, has played with the potential for Force fakery through its central scoundrel, Jod Na Nawood. Jod, who’s played by Jude Law, appears to possess at least a rudimentary command of the Force. Of course, in the pirate captain’s case, appearances are usually deceiving: He’s a mask-wearing trickster who goes by many names. Perhaps, some viewers continue to postulate, his use of the Force is a trick, too. The series seems to invite such speculation: It can’t be a coincidence that almost all of Jod’s Force flexes so far have involved manipulating metal objects—calling a key toward him through the bars of a cell, for instance, or freeing himself from wrist binders. Might his displays of telekinesis stem from concealed magnets or some other artifice that doesn’t depend on high midi-chlorian counts?

Jod’s enigmatic origins—one of a few pleasantly surprising sources of mystery in Skeleton Crew, along with the nature of new planet At Attin and its “Supervisor”—are still a cipher with one episode left in the season. Is Jod/Crimson Jack/Dash Zentin/Silvo/etc. an ex-youngling who survived Order 66, like Third Sister from Obi-Wan Kenobi? The timing doesn’t quite work, considering Law’s age (52) and how long it’s been in-universe since Order 66 (28 years), but Star Wars stories don’t strictly abide by actor ages; even after a retcon, Cassian Andor is close to 15 years younger in Andor Season 1 than Diego Luna was while filming. (For that matter, actors’ real-life appearances sometimes belie their ages: Does Law look 52 to you?) Or maybe, like The Last Jedi’s Broom Boy, Jod is an intuitive adept, a Force neophyte who’s clumsily cultivated a few handy get-out-of-captivity-free tactics during his many misadventures.

In past Star Wars projects, both big screen and small, we’ve seen light siders, dark siders, and every shade of Force alignment in between—even Padawans who have little affinity for the Force. However, we haven’t seen many Force-sensitive characters who only dabble in developing that skill set. (Save for the sequel trilogy’s Finn, who was hardly developed at all.) After all, if you could use the Force, why wouldn’t you? Aside from the fact that for a while there, wielding the Force was a way to earn a visit from Darth Vader?

Law is one of the best actors to make his Star Wars debut during the Disney era, and Jod is a fantastic character, whatever his backstory turns out to be. If he’s an ex-Jedi, it’s particularly poignant that he turned a lightsaber on the kids in Episode 7, echoing Anakin’s slaughter of the younglings at the Jedi temple in Episode III. (Maybe his words—“weak, sheltered, spoiled children”—were projection, reflecting hard-learned lessons about betrayal and self-reliance.) Either abbreviated Jedi training or informal, self-directed dabbling would explain why he has a distorted understanding of Jedi philosophy. And if he’s just a slippery, self-interested hustler who’s hiding some device up his literal sleeve, well, that tracks too. Hell, I’d be happy never to know for sure.

I expect that we will learn the truth, and that Jod isn’t purely a pretender. For one thing, the sound that typically accompanies on-screen Force use in Star Wars—which seems to be a non-diegetic indicator to the audience, not an in-universe sound—is audible whenever he performs some seemingly Force-assisted sleight of hand. But preserving some uncertainty surrounding Jod’s abilities is one of the cleverest ways that Skeleton Crew has tapped into tradition. The history of the franchise has demonstrated this much beyond a doubt: Like Harry Burns, Star Wars characters can’t always tell what’s fake from what’s real.

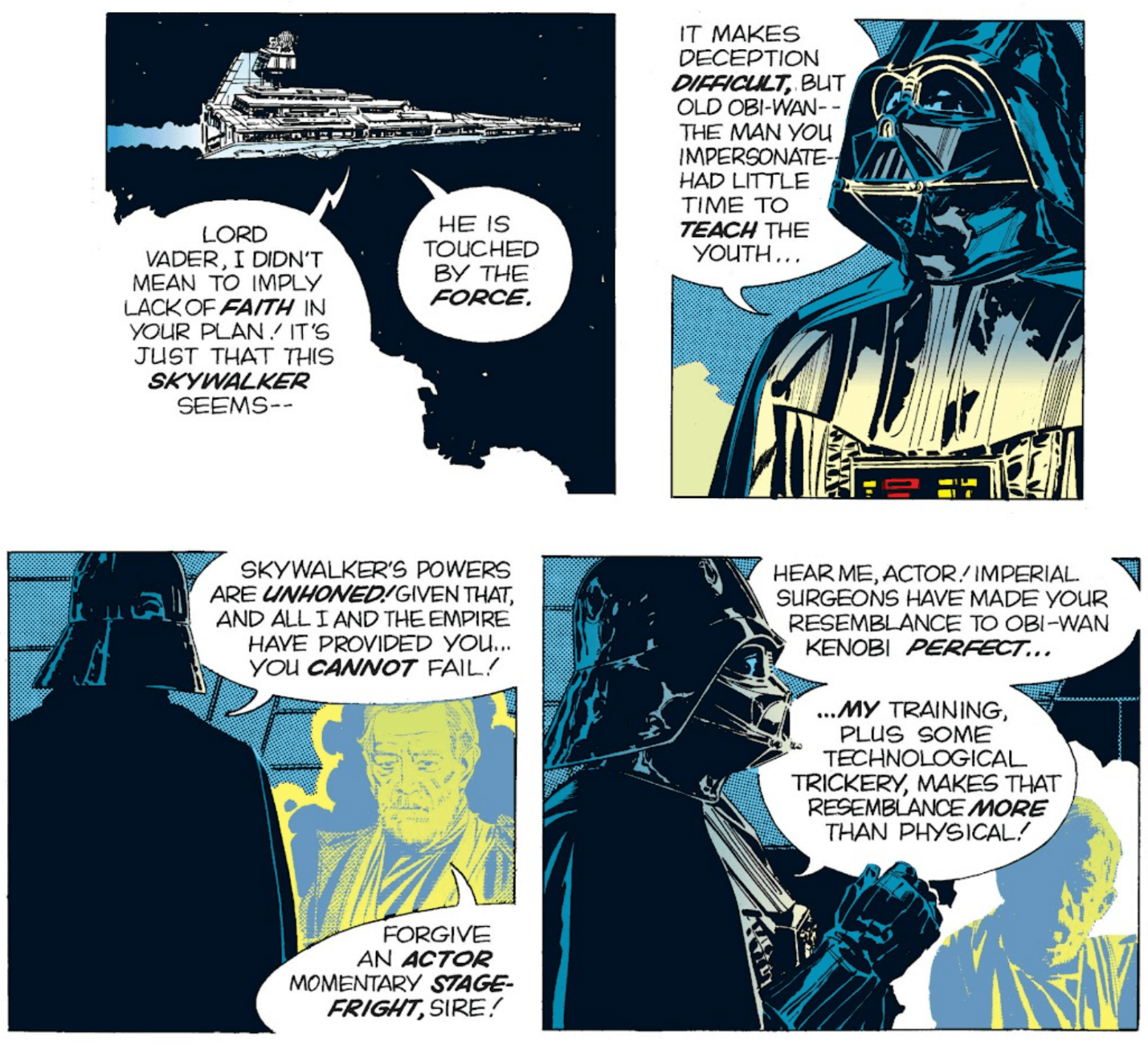

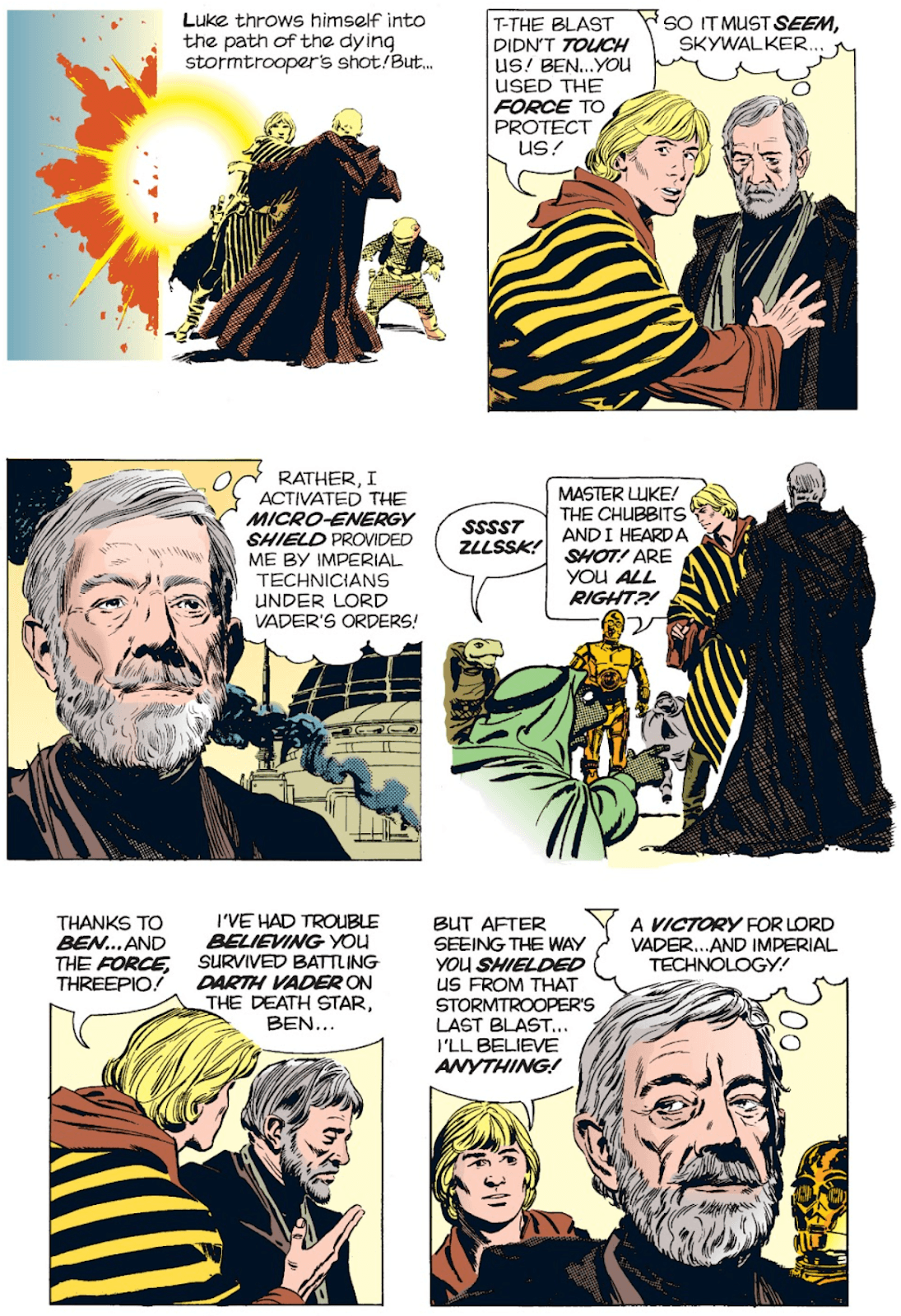

The history of Force frauds date back to at least 1982, when the Star Wars comic strip written by Archie Goodwin and drawn by Al Williamson introduced an Obi-Wan impostor in an arc entitled “The Return of Ben Kenobi.” In this story set between the first two films of the original trilogy, Darth Vader hires an actor to impersonate Obi-Wan Kenobi in order to lure Luke Skywalker into a trap. The actor undergoes facial surgery to look exactly like the deceased Jedi master, and that superficial Kenobi-ness, in tandem with “concealed circuitry that enables [him] to simulate aspects of the Force,” ensnares the young Rebel hero. (The first of these plot devices actually anticipates a plot line produced 30 years later in our galaxy, in which the real Obi-Wan transforms his face to resemble a bounty hunter’s in an effort to thwart a Sith lord’s plot on The Clone Wars.)

Of course, it takes a demonstration of this Faux-bi-Wan’s powers to convince Luke that the old man whom Vader struck down on the Death Star is somehow still alive. That’s where the “technological trickery” comes in.

Ultimately, the Obi-Wan actor plays the part too well, from Vader’s perspective: He starts to sympathize with young Skywalker and, like the actual Obi-Wan, sacrifices himself to allow Luke to escape the dark lord. With that, though, the precedent for Force charlatans was established.

The concept of an Obi-Wan lookalike resurfaced decades later in the 2008 video game The Force Unleashed, in the form of PROXY, a droid assigned by Vader to train Galen Marek (alias Starkiller), a secret Sith apprentice. PROXY is programmed to try to assassinate Galen, on the grounds that what doesn’t kill Starkiller will make the apprentice stronger. PROXY’s holographic capabilities allow him to alter his outward appearance and masquerade (and fight) as any other adversary, as long as he’s equipped with the proper combat module. Obi-Wan isn’t PROXY’s only impression—he also does Darth Maul and other famous Force users—but he describes it as his “most dangerous.” As a droid, PROXY is devoid of authentic Force powers, but he can handle a lightsaber, and he’s also equipped with built-in repulsors and tractor beams that enable him to mimic Force pulls and pushes.

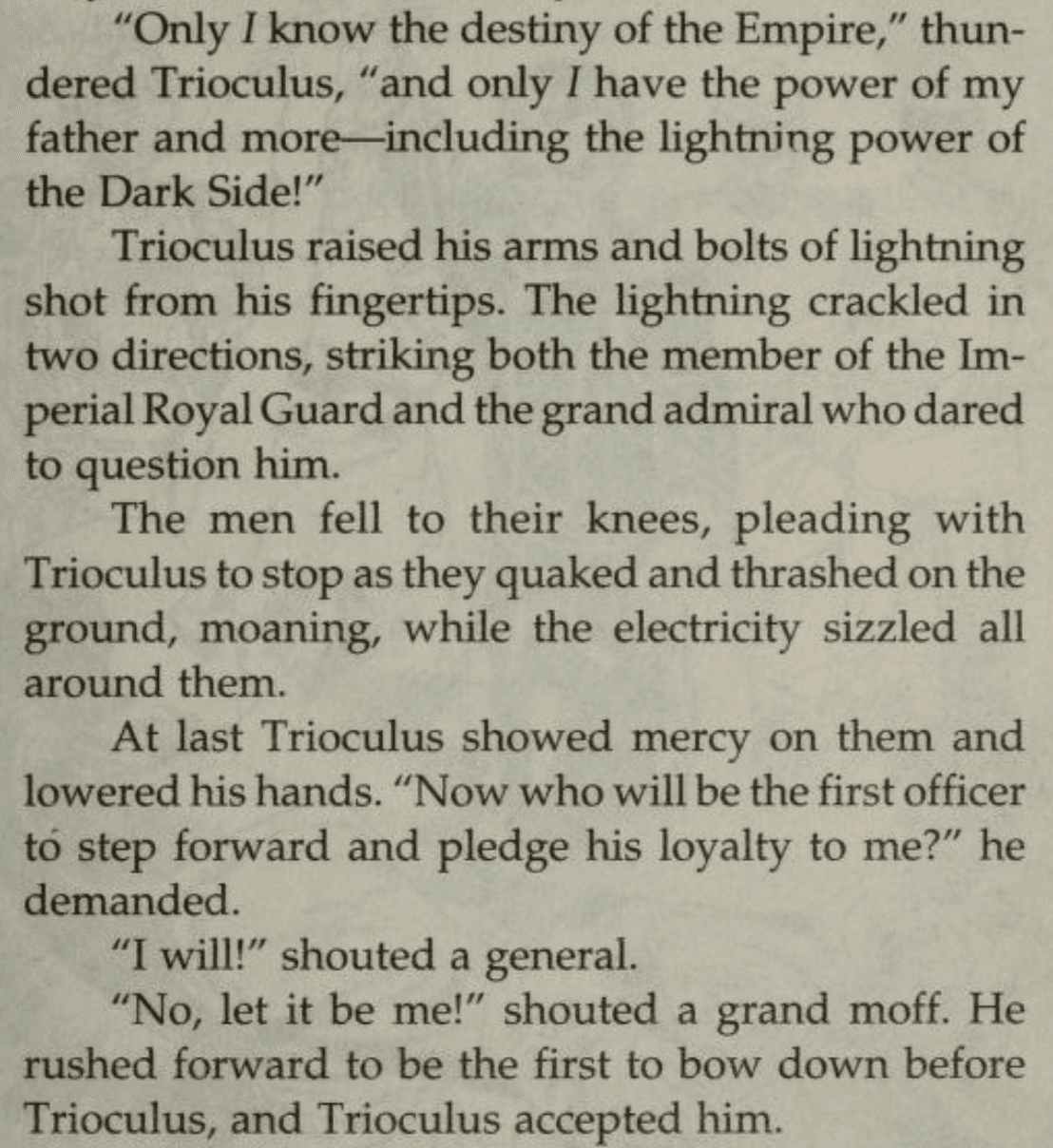

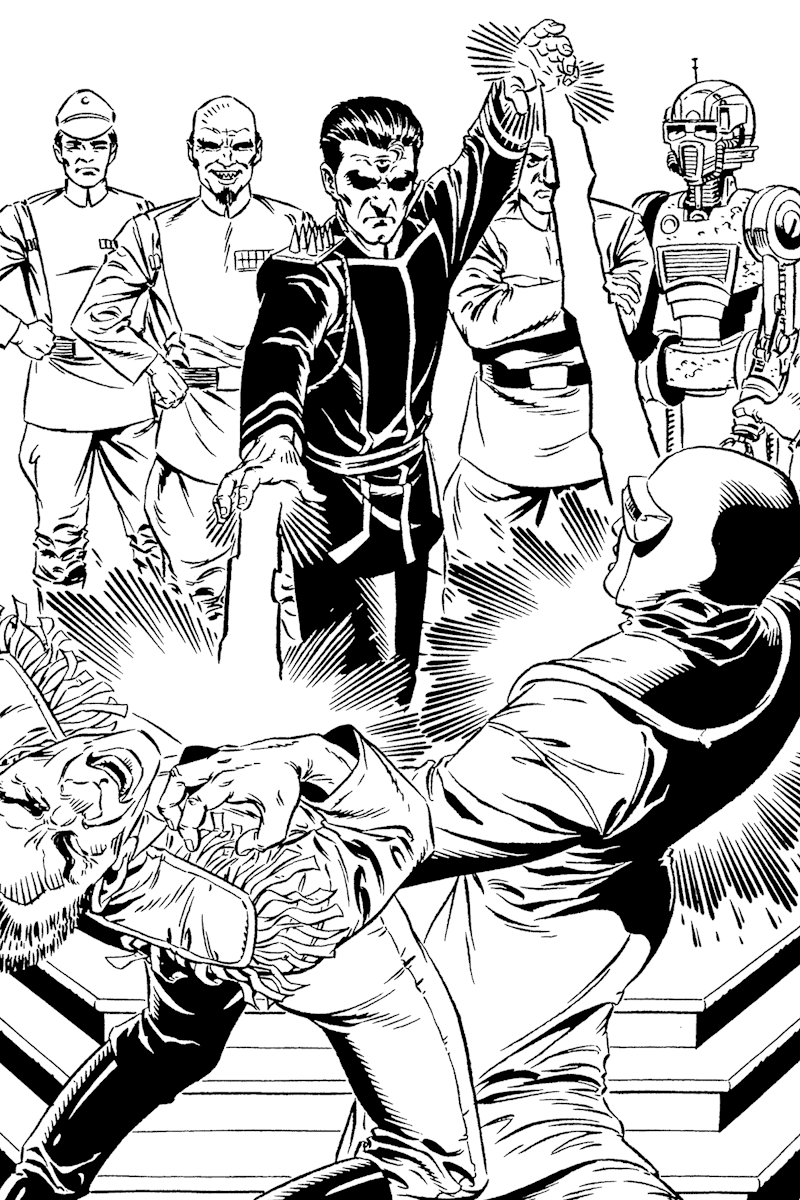

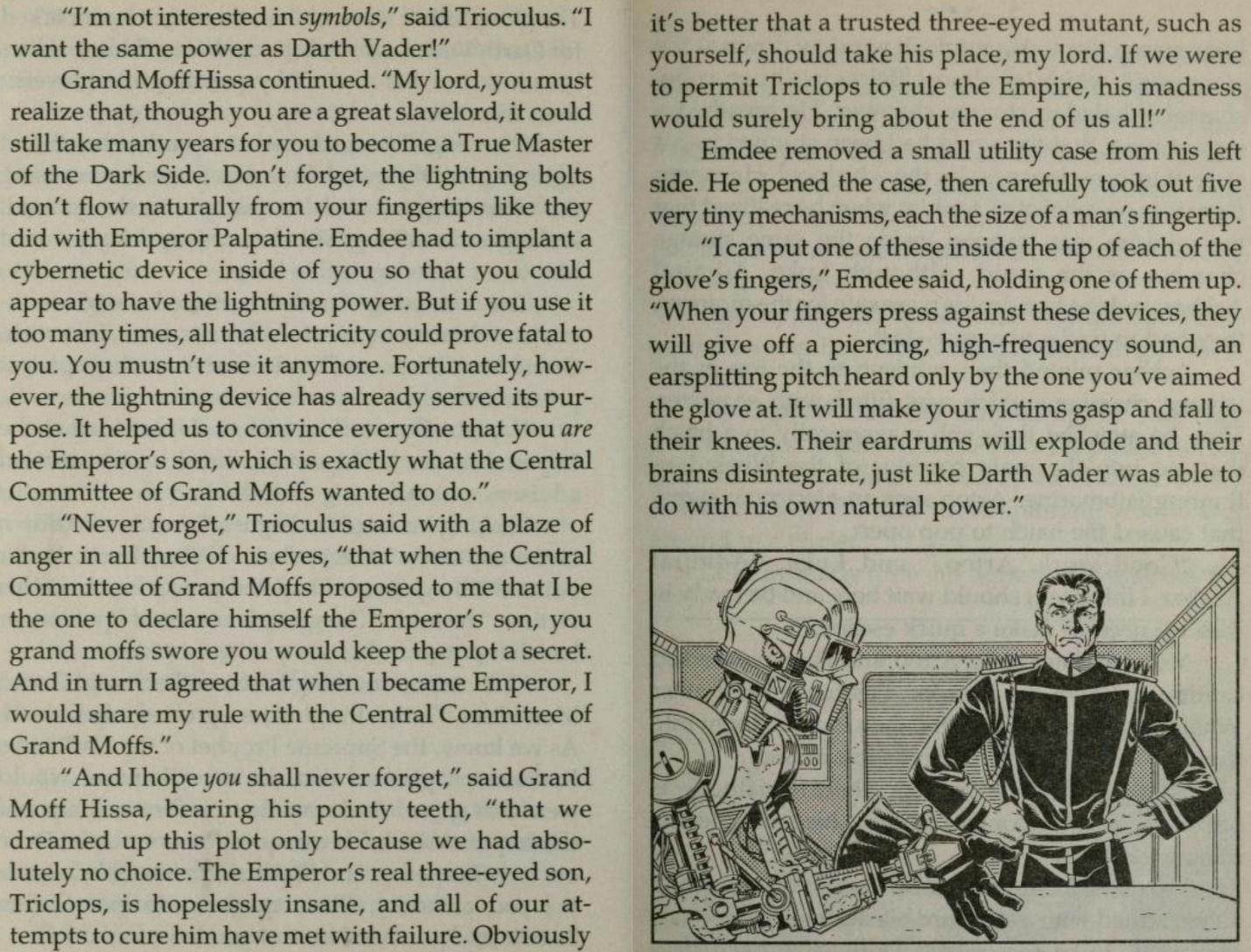

The practice of pretending to wield the Force is far from an Obi-Wan-oriented phenomenon. The Disney-decanonized Legends corpus is replete with examples of Force phonies—my personal favorite (in a so-goofy-it’s good sort of way) being the tale of Trioculus, a character who appeared in the Jedi Prince series of junior novels published in 1992 and 1993. Trioculus—not to be confused with Triclops, who appears in the same series—is the self-proclaimed son of Emperor Palpatine. A mutant who has a third eye on his forehead (in case you hadn’t guessed) and rules as the “supreme slavelord” of the spice mines of Kessel, he’s installed by the Grand Moffs as the new Emperor after Palpatine meets his end. Although he has no Force sensitivity, cybernetic implants in his fingertips allow him to project convincing-looking (and -feeling) “Force” lightning, which helps him command the Moffs’ respect and consolidate control. Few others know that his abilities come more from machine than man.

To further strengthen his claim (and his power), Trioculus searches the galaxy for—and finally finds—the glove of Darth Vader. But the glove didn’t give Vader his knack for Force-choking, and it doesn’t do anything for Trioculus except look kinda cool—which means more modifications are in order to make the monarch seem scary.

These Force prosthetics possess real power—albeit not the kind derived from midi-chlorians—but they hurt Trioculus too. (Eventually, he loses his sight, at least temporarily.) In the end, the threat posed by Trioculus and his faked-but-nonetheless-potent powers was extinguished by a human replica droid that looked like Leia Organa; the Leia decoy droid skewered Trioculus with its laser eyes. Perhaps you’re starting to see why Disney decanonized stories such as this one. (RIP, my sweet, extremely silly Trioculus, both in the Jedi Prince series and in the Star Wars canon.)

The Trioculus trope was repeated in the 1997 conclusion of the Junior Jedi Knights series of young reader novels, in which a character called Orloc (rhymes with warlock!) declared himself to be an “Emperor’s Mage,” a member of a group called the Prophets of the Dark Side. Orloc is a false prophet, but like Trioculus, a persuasive one. He’s a little lower-rent than Trioculus, though: Real, lethal lightning is beyond his budget. Orloc uses a spangled robe to control speakers, flickering lights, and sprinklers,and other equipment that produces a sound and light show and makes it look like Orloc can summon storms and lift heavy objects. He’s no match for real Force-sensitives, once they’re onto his act.

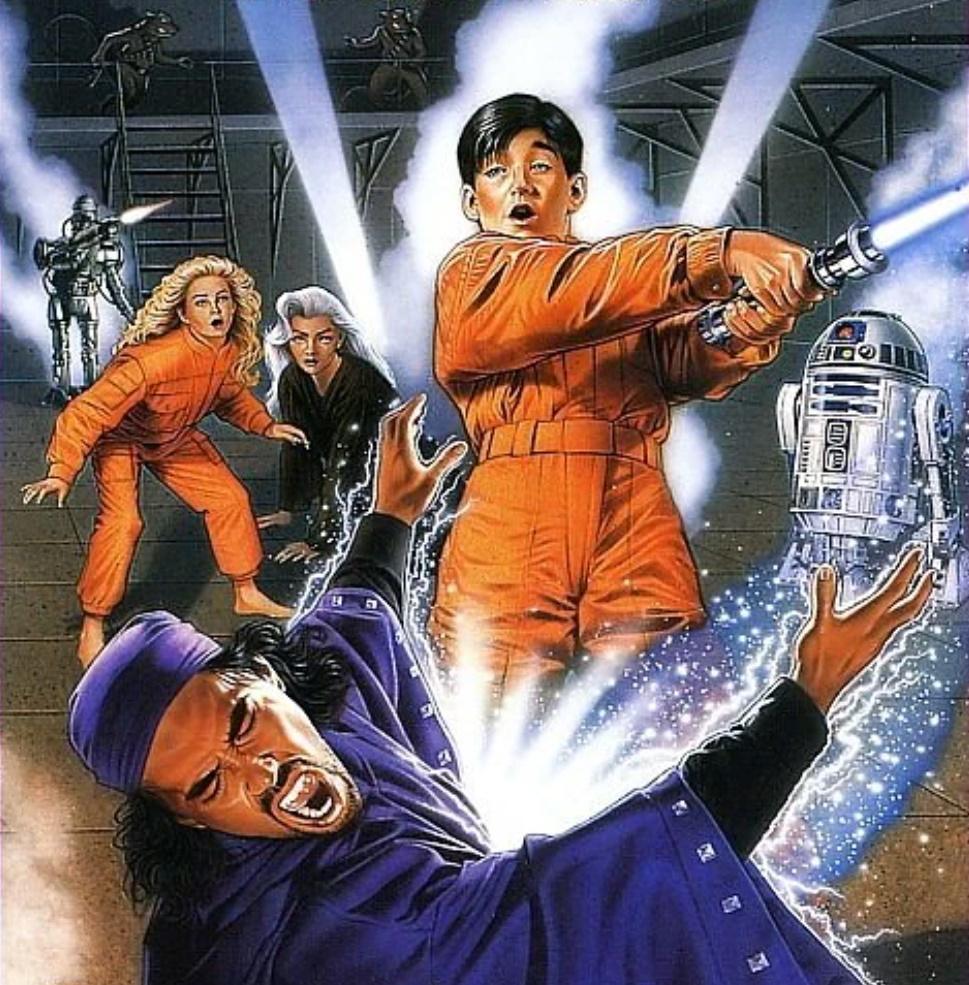

Another ’90s character related to this lineage of Force fabulists is Anja Gallandro, who appeared in the last three entries in the 14-book Young Jedi Knights series of young-adult novels. Gallandro, who lacked any aptitude for touching the Force, used and abused spice that heightened her senses and reflexes and helped her fight like a Jedi (lightsaber and all).

A lot of Legends stories played pretty fast and loose with Force powers. A character called Jorj Car’das, who first appeared in Timothy Zahn’s 1998 novel Vision of the Future, gained some small amount of Yoda’s power after Yoda healed him following an encounter with a dark Jedi. Despite still being at most minimally Force-sensitive, Car’das learned to wield the Force to some extent, after studying with a species of non-Jedi, non-Sith Force monks called the Aing-Tii. Legends releases such as the Jedi Knight games also featured objects that could confer Force powers, including the Scepter of Ragnos, or Artusian crystals that, when infused with the power of the Valley of the Jedi, could create Force-sensitive shadowtroopers. (Again, Legends was wild.)

The last Legends instance I’ll cite comes from “Reputation,” a 2012 short (origin) story published in the magazine Star Wars Insider just before Disney purchased the Star Wars franchise. It’s about bounty hunter Cad Bane, who first appeared in The Clone Wars and later leaped to live action in The Book of Boba Fett. “Reputation” finds a young Bane working for a crime boss who’s been harried by a Jedi. He uses a thermal detonator and carries a lightsaber that looks more like a spear. And as for his Force jump: “For just a split second, as the Jedi crouched, the bounty hunter swore he spotted tiny flashes of light from the soles of the man’s boots.”

In addition to the jetpack boots, the “Jedi” (who’s really an assassin hired by the Hutts) uses “monofilament cable with a magnetic grapple” to snag enemy blasters from afar and a gas emitter in his wrist gauntlets to “Force” choke his target. Bane admires the ruse and decides to model his own go-go-gadget arsenal on it, which prepares him to hold his own against real Jedi down the road.

Bane is still canon; that particular tale is not. But the current canon does include a few examples that laid the groundwork for doubts about Jod—even excluding cases of mistaken identity, like the time Jar Jar Binks was mistaken for a Jedi in Season 1 of The Clone Wars. (Everyone knows Jar Jar is actually a Sith lord.)

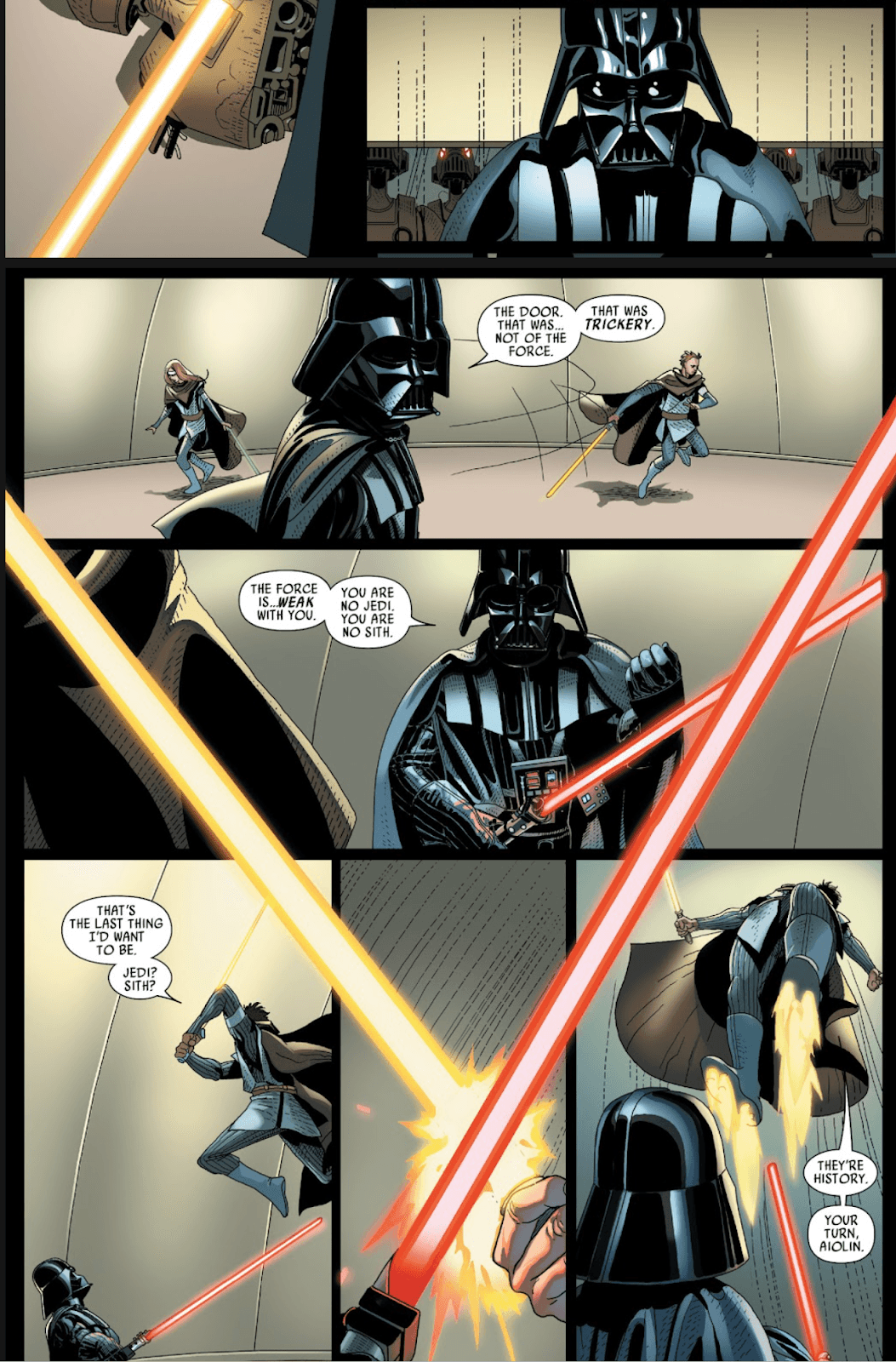

In the Darth Vader comics published in 2015, the Emperor’s apprentice battles a cohort of rivals genetically and cybernetically enhanced by a mad-scientist servant of Palpatine named Cylo, who bases parts of their design on General Grievous.

“The Force is obsolete,” Cylo (or, well, one of his clones) tells Vader. “These are its successors.” Predictably, the Emperor’s helmeted enforcer isn’t impressed by the technological terrors Cylo has constructed; he considers them heretical, blasphemous abominations. Cylo’s creations are formidable, but their “trickery” can’t compete with the power of the dark side.

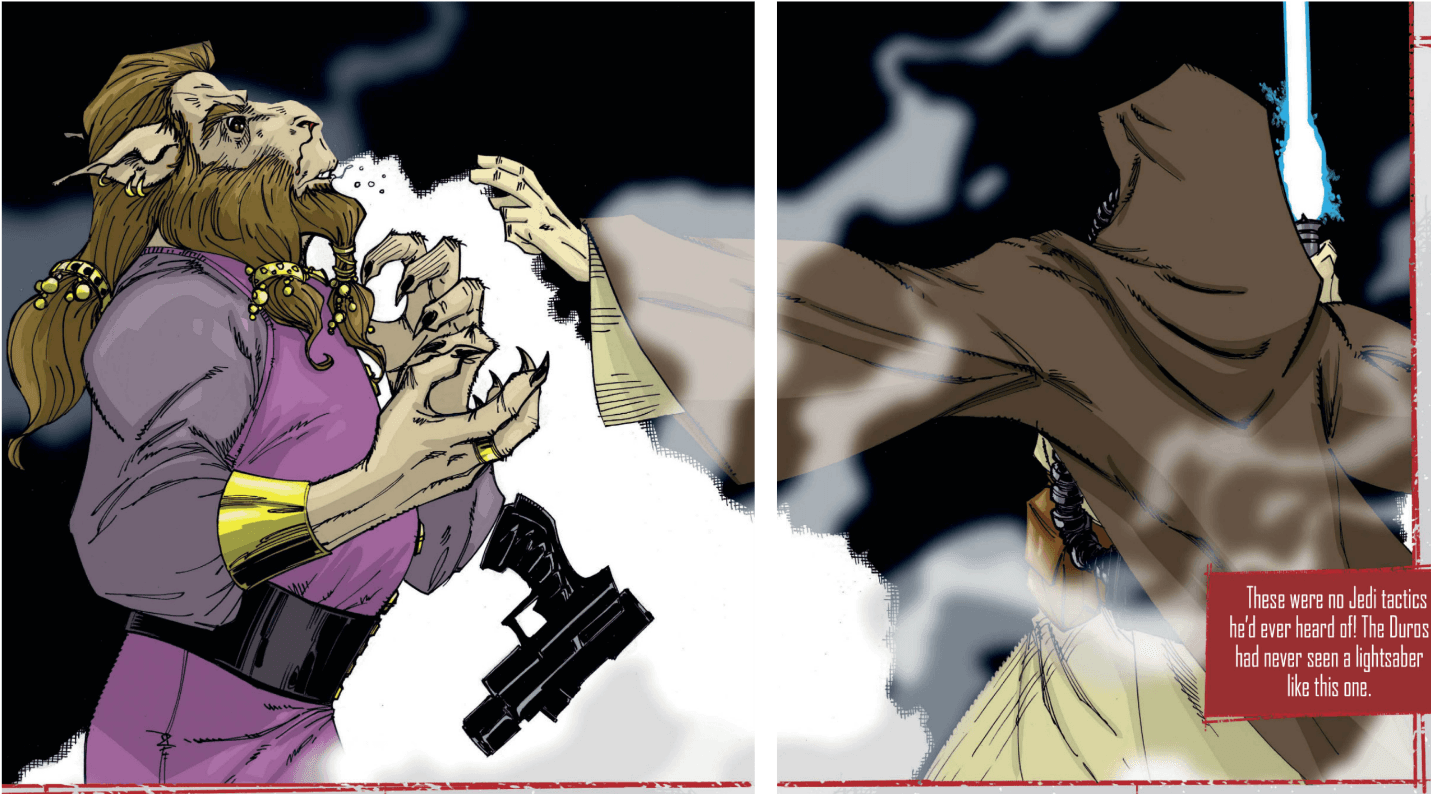

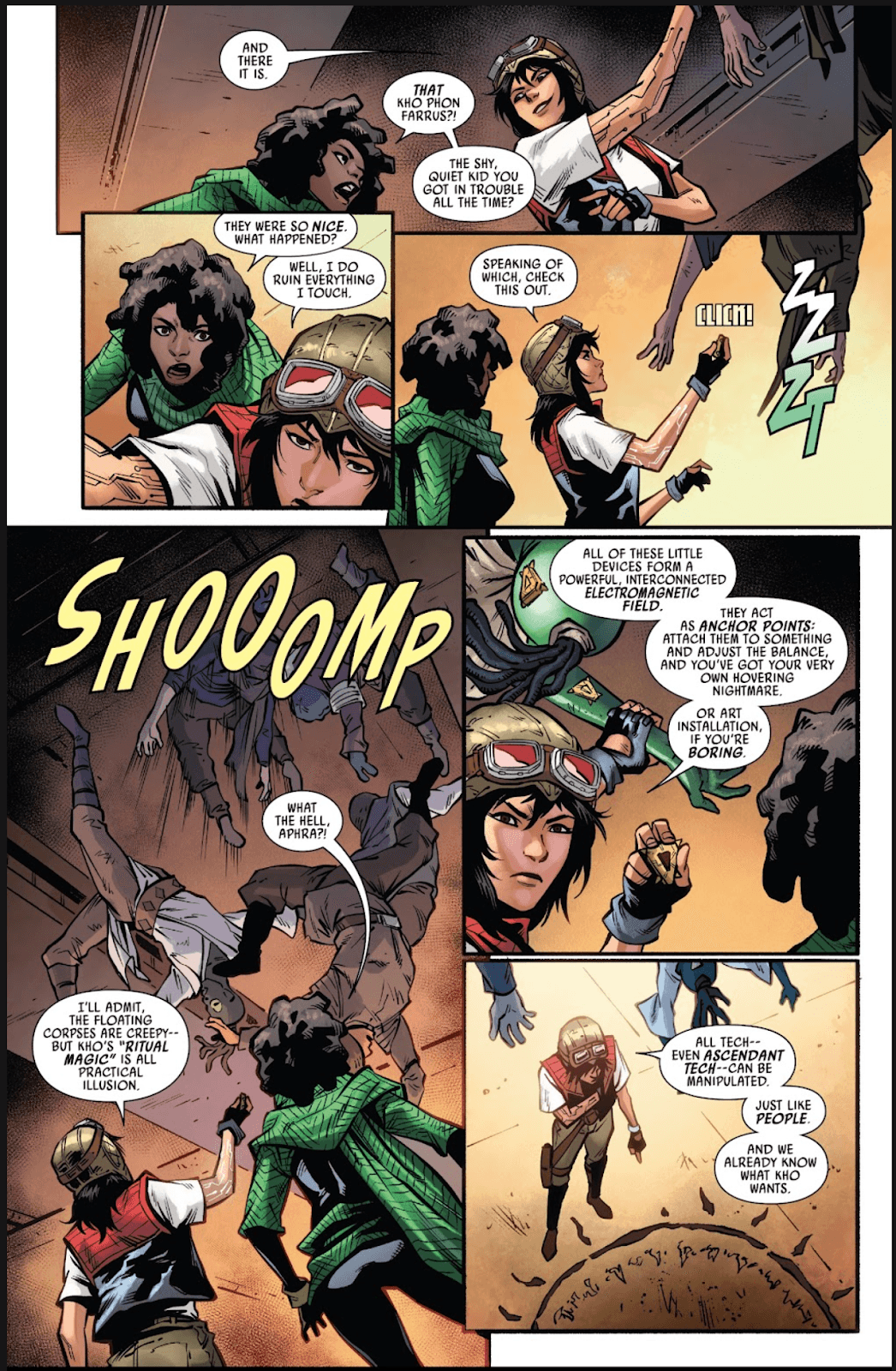

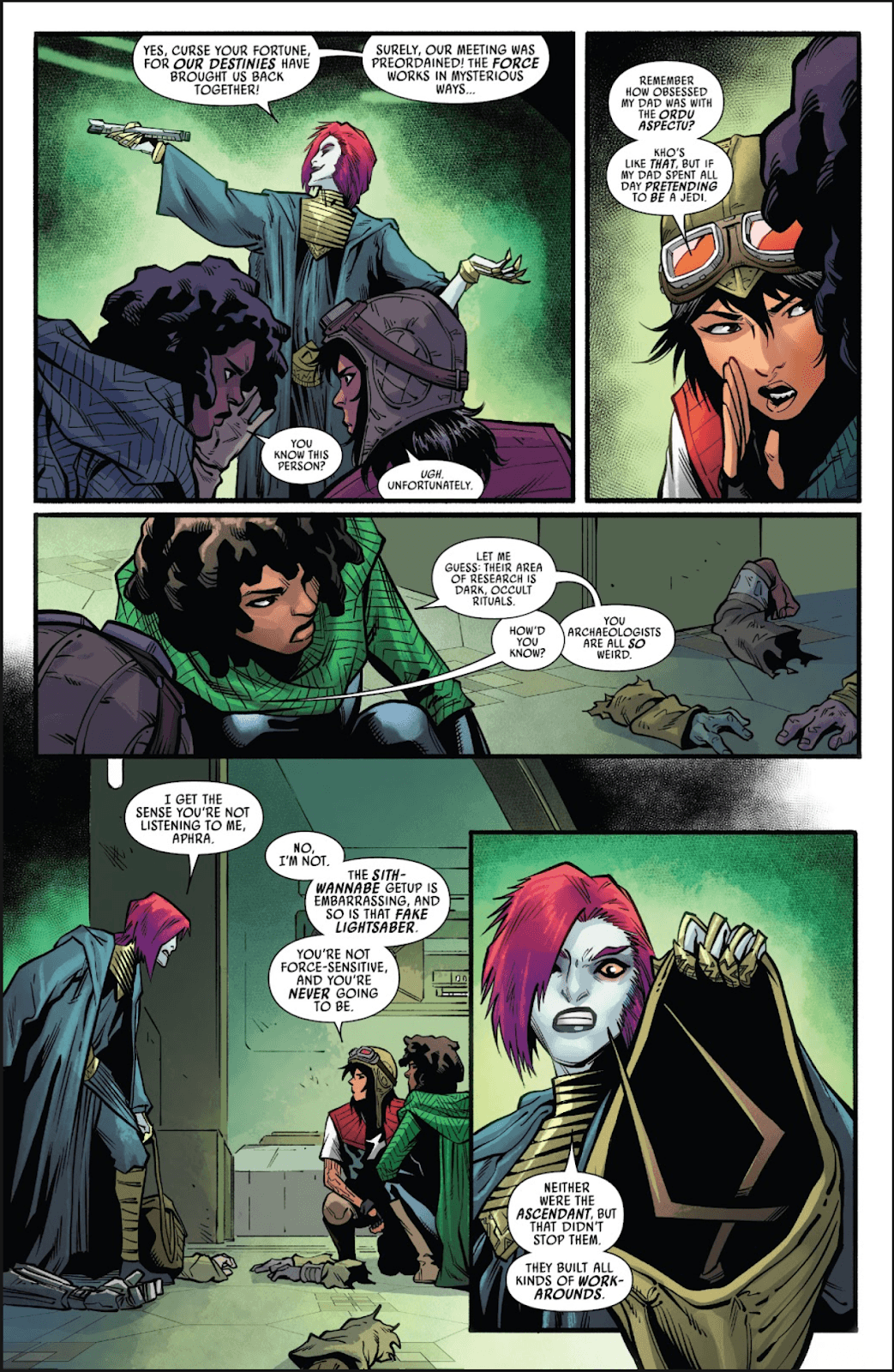

Years later, in an early 2022 arc of comic Doctor Aphra, the popular eponymous protagonist (who debuted in that 2015 Darth Vader run) tangles with a dark-side wannabe named Kho Phon Farrus, who uses electromagnet fields and ancient artifacts to simulate Force sensitivity.

Aphra is less than impressed with Farrus’s Force “workarounds.” “The Sith wannabe getup is embarrassing, and so is that fake lightsaber,” she says. “You’re not Force-sensitive, and you’re never going to be.”

Later that year, Obi-Wan Kenobi brought a Force huckster to the screen, courtesy of Haja Estree, the cut-rate, Jedi-cosplaying swindler played by Kumail Nanjiani. “The Force is so strong with you,” one of Estree’s grateful marks tells him. “Yeah, I know,” he responds, immodestly—moments before Obi-Wan, an actual Jedi, exposes the “remotes and magnets” he uses to perpetrate his scams. “Con artist” is too flattering a term for this Force grifter, considering the transparency of his shams. “Mountebank,” maybe.

If Jod is a fraud—which the preponderance of the evidence still argues against—he’ll have plenty of company in the annals of Star Wars. If anything, it’s surprising that fake Force-sensitives aren’t more common. After all, many of the physical manifestations of the Force are easily reproduced by bog-standard Star Wars substances or technology, which make marvels such as droids, blasters, and interstellar travel. Of course, equipping every Star Wars character with Dune-style shields and suspensors would, in effect, make Jedi less special—or, at least, less uniquely fun to imitate. (The Bene Gesserit Voice is entertaining too, but it doesn’t work on supermarket doors.) As long as Star Wars has existed, fans have indulged in Jedi dreams. Small wonder, then, that at least some inhabitants of the galaxy far, far away would do the same—or that generations of Star Wars storytellers would find it useless to resist sticking the idea in their characters’ heads.