“Welcome back, Mark S.,” Mr. Milchick says near the start of the Season 2 premiere of Severance. “Been a minute.”

For Mark S. (Adam Scott), a “severed” employee who remembers none of what happens to his “outie” counterpart who lives outside Lumon Industries, the events of Season 1 literally seem to have happened a minute ago. For his outie, five months have passed (according to Mr. Milchick, at least). For Severance viewers, however, Mr. Milchick’s statement sounds like meta-commentary on the Apple TV+ show’s long layoff: Almost three years have elapsed since the start of Season 1, or almost 33 months since the Season 1 finale. Which means that many spectators must feel somewhat severed from the experience of watching that first set of episodes back in early 2022.

In prior eras of television, five months was not an abnormal break between seasons. Take Lost, for instance—another mystery-box-style sci-fi series that features an inscrutable, sinister setting, out-of-place animals, and enigmatic numbers on old-school computers. (Unsurprisingly, Lost is one of Severance writer, producer, and showrunner Dan Erickson’s favorite shows.) Lost’s two-part second-season finale aired on May 24, 2006. Its Season 3 premiere appeared on October 4, 2006—a little less than five months later. If anything, that turnaround seemed slow: The gap between the end of Season 1 and the start of Season 2 was a little less than four months.

These days, that seems inconceivable. Squid Game was gone for more than three years before the second season binge-dropped last month (though Season 3 will follow this year). Arcane was off for almost three years. Fans of Stranger Things, which will conclude later this year, endured an almost 35-month gap between Seasons 3 and 4; the interlude between Seasons 4 and 5 will likely exceed that. Almost two and a half years will have gone by between Andor seasons when the Star Wars series returns in April; ditto for Season 6 of The Handmaid’s Tale.

Even shows that utilize 2D animation aren’t immune to interminable waits: Blood of Zeus went quiet for more than three and a half years after its first season, and Invincible disappeared for more than two and a half years, then took a midseason siesta after four episodes. Speaking of which: Even single seasons are lasting longer. Outlander took a break of more than 15 months in the middle of Season 7; the season started in June 2023 and will end on Friday. Yellowstone’s fifth and final season, which ended last month, had a hiatus of more than 22 months; the season finale aired more than 25 months after the season premiere.

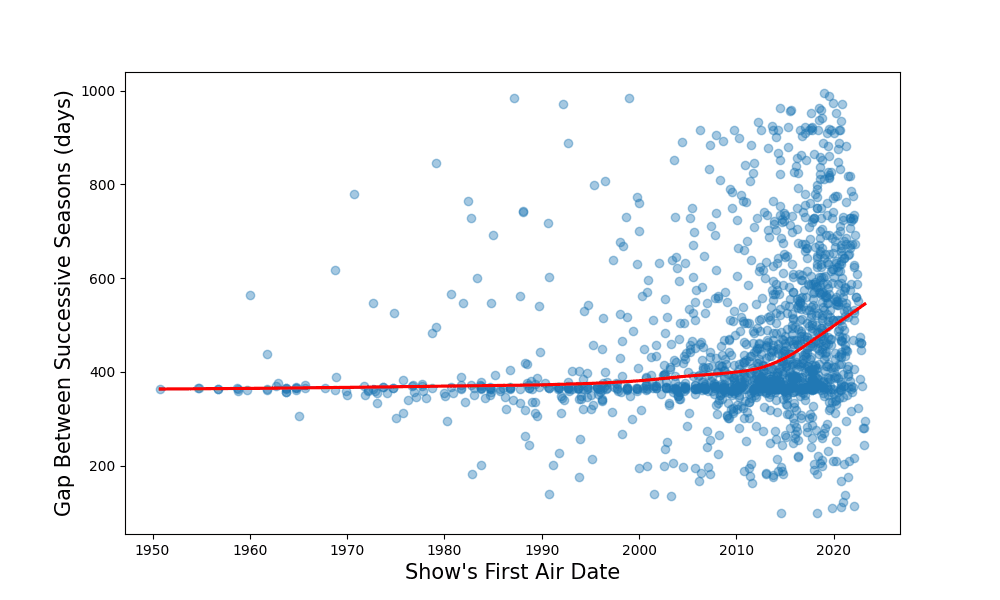

Let’s turn these anecdotes into data. The graph below shows the average time (in days) between the starts of successive seasons, by year. The sample is limited to series with at least 100 IMDb user ratings, includes only English-language releases (or shows translated into English), and excludes kids’ shows, game shows, reality shows, or news shows.

Clearly, there’s been a dramatic uptick in the typical time between season premieres, which had hovered around one year for decades before beginning a gradual increase around the turn of the century and then starting to spike in the mid-2010s. As Jake Kleinman wrote for The Ringer this week, “In our current streaming era … the idea that a new season will come out every year feels charmingly antiquated.”

If anything, that chart underrates how much longer more recent interludes between seasons really feel for viewers. Seasons are composed of fewer episodes than they used to be, and some seasons are binge-dropped, which means that most shows tend to go longer without actively airing new episodes. To go back to Lost: ABC pushed out new seasons of that series on a yearly basis, and the first few seasons ran for 23-25 episodes apiece, which meant that the show was in season for most of the year. It seemed to be on all the time. Compare Lost’s schedule to, say, that of The Bear, one of the few popular shows that still comes out like clockwork on an annual cadence. A season of The Bear runs for 10 episodes, max, and it’s binge-dropped, so fans who tear through a new season quickly have a full year to wait until the next.

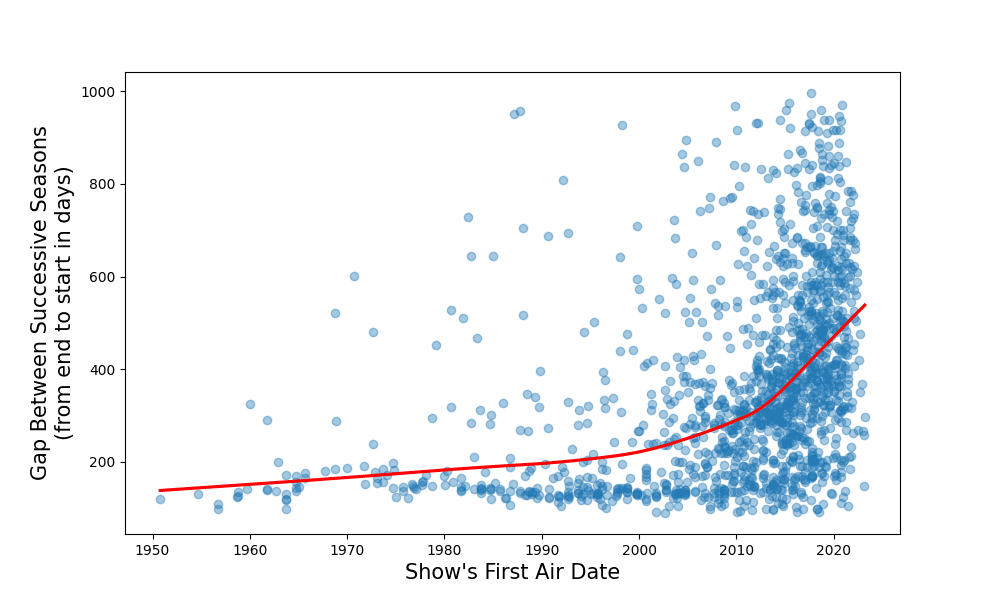

Thus, the next chart, which is drawn from the same pool of shows, displays the data a different way: this time, by showing the annual average gap (in days) between the airdates of the last episode of one season and the first episode of the next.

That’s an even more drastic increase. (The upward slope is slightly steeper for dramas, such as Severance, than for comedies.) The average wait for the next season after the preceding one ends is approximately three times as long as it once was. “Next time on” has never seemed like such a frustrating tease of a phrase.

Of course, a caveat is required. The past few years have been far from normal (or what passes for normal) in the entertainment industry. The COVID-19 pandemic and the 2023 actors and writers strikes derailed and postponed many a big- and small-screen production; now, the L.A. fires are poised to do the same. Most (though not all) shows that have come out lately or are due out soon felt those effects; for instance, the strikes shut down production of Severance for roughly eight months.

That said, Severance is a painstakingly (and deliberately) produced show under the best of circumstances: “We’re on the same really slow schedule we’ve always been on,” producer and director Ben Stiller tweeted shortly before the strikes. Average wait times for TV to return began growing well before the pandemic and the strikes; those events only exacerbated an existing trend. “The pandemic and strikes aren’t the sole reasons for the lengthening gaps, though the strikes probably made long gaps for some shows (Severance and The Night Agent come to mind) even longer,” says Rick Porter, who covers the television industry for The Hollywood Reporter.

What else could be causing more protracted timelines? Sources seem to agree on a few factors.

“This is a function of both the changing business model of television and the emergence of the new business of streaming,” says Matthew Belloni, a founding partner of Puck who hosts the Ringer podcast The Town. “TV used to be a purely free, ad-driven business that functioned on an annual calendar. Shows were conceived and produced in the winter, sold to advertisers in the summer, and then they aired during a season from the fall through the spring. As TV shifted to subscription via cable and as streaming supplanted linear as the platform for scripted shows, the business model worked differently. Shows don’t need to be on an annual schedule, because the platforms just need a regular cadence of any content to satisfy subscribers and keep them from canceling.”

Even so, subscriber churn has become an increasingly severe problem for streamers (with the notable exception of Netflix) as services multiply and raise prices. If it were easy to make quality TV quickly and give people more reasons to keep paying, companies probably would. Which means that there must be additional reasons for the slowdown.

Belloni mentions one of them: “The production value of TV has increased as consumers have demanded more, and higher production value takes more time (and costs more).” It’s probably not a coincidence that the time between seasons started soaring just as the concept of “prestige TV” took root.

The makers of Severance, as “prestige” a production as any sci-fi series, acknowledge that they’re the tortoises of TV: “We do shoot pretty methodically, and we probably don’t turn around as many pages of script per day as a lot of other shows,” Erickson told Vanity Fair. “That comes down to just trying to make sure that we get it right.” Patricia Arquette, who plays Ms. Cobel on Severance, recalled to Kleinman that while filming Season 1, she picked up a self-help prop book on set, expecting it to be blank inside, only to find that Erickson had filled it with words. That attention to detail helps explain Severance’s appeal—as well as the pace of its production. On a traditional network drama with 22-plus-episode orders and short recesses between seasons, deadlines and budgets probably wouldn’t have allowed for world-building that wasn’t visible to viewers.

The Entertainment Strategy Guy, a former network executive who analyzes the streaming landscape on Substack, confirms that “the delay between seasons is real, and I think one of the bigger changes from moving from a broadcast/cable model to a streaming model.” He echoes, “The show budgets and effects are also bigger, and hence require more production time. This doesn’t apply to every show, but certainly bigger-budget genre shows like House of the Dragon, The Last of Us, or some other big Netflix shows.”

And as Porter points out, filming is sometimes just the start of the protracted process that eventually delivers a broadcast-ready TV tentpole. “Shows like Stranger Things, the Game of Thrones–verse, and even something like Percy Jackson and the Olympians on Disney+ have huge amounts of VFX and other postproduction work that goes on for months after filming ends,” he says, adding, “That builds in more time between seasons.” Especially because the VFX industry has been strained to the breaking point as studios have flooded the market with effects-forward franchise fodder. (Video games are also taking longer to create, for some similar reasons.)

Just as there are only so many VFX studios, each of which can accommodate a finite number of jobs, there are only so many in-demand actors, who have only so much time in a year. “If a show signs an A-list actor up for a season that has eight or 10 episodes, that person probably has other jobs lined up, too,” Porter says. “So to get them back for the next season, the show has to work around or wait out the other commitments. That applies to working actors as well, who need more than a single eight-episode show a year to make a viable living.” It’s a plus that TV actors have time to take on a wider assortment of roles than they could when booking one leading role was a nearly year-round commitment, but it turns casting, booking, and scheduling into a less lethal game of Mingle from Squid Game Season 2.

Writers can be a bottleneck, too. “Solo writers tend to have longer writing times than writing staffs, and many streaming shows are auteur driven, meaning they have longer writing times than, say, sitcoms or procedurals of previous decades,” says the Entertainment Strategy Guy. One simple solution, in theory: more writers rooms. But there’s a fairly low ceiling on how quickly streaming series can ramp up production on a new season because of the way streaming services make programming decisions. As the ESG notes, “Streamers in many cases wait to see a show’s performance before green-lighting future seasons. Meaning if a show comes out, and a streamer waits four to 12 weeks for the data, and it takes a year or more to produce the next season, then the math just shows that that series won’t come out on an annual schedule.”

The ESG observes that this delay “is exacerbated when writing doesn’t start before a new season comes out”—a reality of streaming’s less modular, seat-of-the-pants approach to production. Or, as Porter puts it, “Even if it’s not a binge release, streaming shows tend to write and shoot an entire season before it premieres. If there’s then a month or two before it’s renewed, the process starts all over again. The old network model has production on later episodes happening while the first part of a season is running, which is more hectic but means that your favorite procedural is still premiering a new season every September.”

In some cases, absence may make spectators’ hearts grow fonder—or even afford time for word of mouth (or an appearance on a larger streaming service) to build buzz. In other cases, a lengthy intermission could have the opposite effect.

“I think it can be an obstacle for viewers,” says Porter, who points out that the U.S. audiences for House of the Dragon and The Rings of Power shrank slightly after close-to-two-year recesses, and that The Umbrella Academy, which had been one of Netflix’s bigger shows, “fell off pretty badly” in its third season following a two-plus-year pause. “Really big shows will survive an overly long break, but I don’t know if ones a tier or two below that can,” he says. “On the flip side, The Bear and Only Murders in the Building have premiered pretty much one year after their last season did every time, and they continue to do really well.”

Porter notes that FX cited the strike-driven gap of more than two years between seasons of The Old Man—less common for a series that originally aired on a linear channel than it is for native streaming shows—as a culprit behind the show’s cancellation after its second season. “I do think long breaks can hurt a show, but I haven’t tried to do a data analysis on it, and that’s a pretty messy data problem to solve when you account for all the variables,” the ESG says. “That said, I think the default position should be a long break hurts a show, not helps.”

Granted, it’s not as if viewers have ever run out of TV in an era when several hundred scripted originals air each year; there’s always something coming soon. The downside of this model from an audience perspective, aside from delayed gratification for individual shows, is that it’s easy to forget what happened in previous seasons by the time some of these series return. After a two- or three-year break, a two- or three-minute “previously on” montage doesn’t quite cut it. Consequently, many viewers seek out print refreshers or more detailed recaps on YouTube, or even resort to rewatching previous episodes or seasons. The latter solution may not be a bad thing from a streamer’s perspective—it means more time on the app—but there is an opportunity cost to revisiting old TV: having less time to try new TV. Plus, even with fewer episodes per season, rewatching a TV show’s back catalog in advance of a new season’s arrival is a more daunting proposition than rewatching a movie before its sequel comes out.

Longer layoffs could also affect how stories are structured, or at least how well they land. Consider the impact on cliff-hangers. When Star Trek: The Next Generation transformed Captain Picard into Locutus of Borg in 1990 Season 3 finale “The Best of Both Worlds: Part I,” fans faced what felt like an agonizing period of anticipation for the Season 4 premiere. But the wait for that two-episode arc to be continued wasn’t really that long: “The Best of Both Worlds: Part II” aired all of three months later. Now, a cliff-hanger could precede a multiyear hiatus. Which truly is a long time for today’s Picard equivalents to keep clinging to life—and for viewers to maintain their grasp on plot points, their attachment to fictional characters, and their curiosity about what will come next.

Perhaps the industry’s post-peak-TV production downturn will make scheduling conflicts scarcer and streamline production pipelines: If streamers make fewer shows, they may commission more of the ones that are still in their lineups. Even a moderate reduction in turnaround time would leave us a very long way from the days of Gunsmoke, which initially boasted 39-episode seasons and inter-season lulls of no more than three months. (When that Western started airing in 1955, there were only a few networks, and not much on them.) Yes, there was much more filler back then, but there was also a steady supply of the most beloved shows—enough for spectators to establish a TV-viewing rhythm. There has to be a happy medium between last century’s bloated episode orders and today’s tiny ones.

As for Severance, the series’ showrunner responded with what Kleinman described as a “soft yes” when asked whether the wait for Season 3 would be shorter. “We’re always trying to tighten it,” Erickson said. If the creators need extra incentive to pick up the pace, the potential for a larger, more engaged audience could be the perfect perk.