In January 2024, director Steven Soderbergh returned to the Sundance Film Festival. His debut feature—sex, lies, and videotape—won the Audience Award there in 1989 and its subsequent success at the box office helped fuel the rise of Miramax and the American independent film boom of the 1990s. This time, he was in Utah to premiere Presence, his first-“person” reimagining of a haunted house story.

Soderbergh’s mind-boggling 34 full-length films in between those two festival appearances lay out the multitude of ways that movies have reached audiences over the past 36 years. He’s made crowd-pleasing and star-led pictures for major studios, polarizing and microbudget fare for indies, a prestige-y Best Director Academy Award winner for a now defunct arthouse shingle, small films that collapsed the window between their limited theatrical release and their appearance on paid video on-demand (PVOD) platforms, and well-regarded but little-seen movies for three different streaming services. At this point, there isn’t a filmmaker around who’s more aware of the possibilities and pitfalls of the different distribution channels.

Multiple suitors wanted to put out Presence, but Soderbergh chose Neon, the adventurous and often off-beat distribution and production company that’s become a key force in the revitalization of global independent cinema. He might not have known it, but Neon was on the precipice of its biggest year yet.

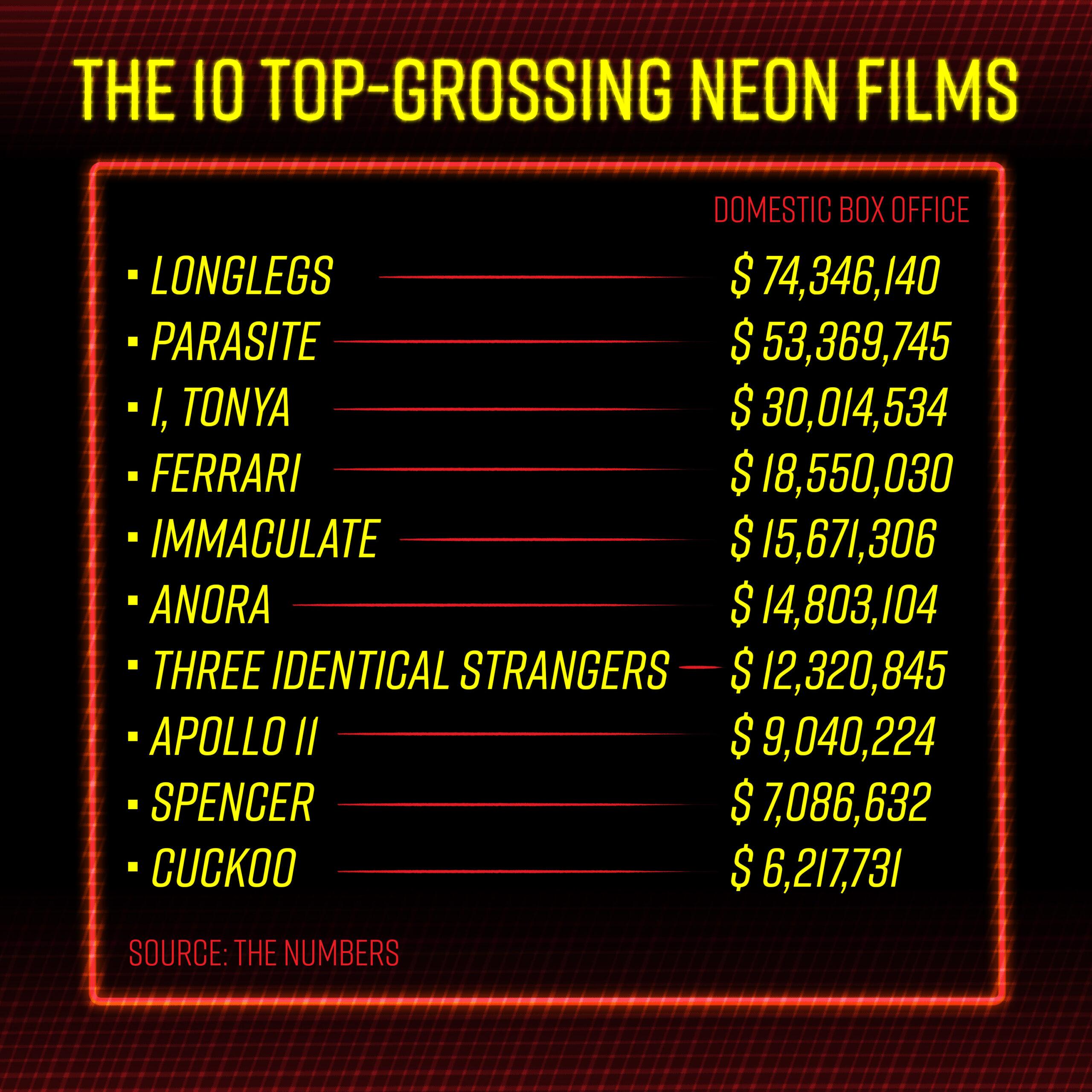

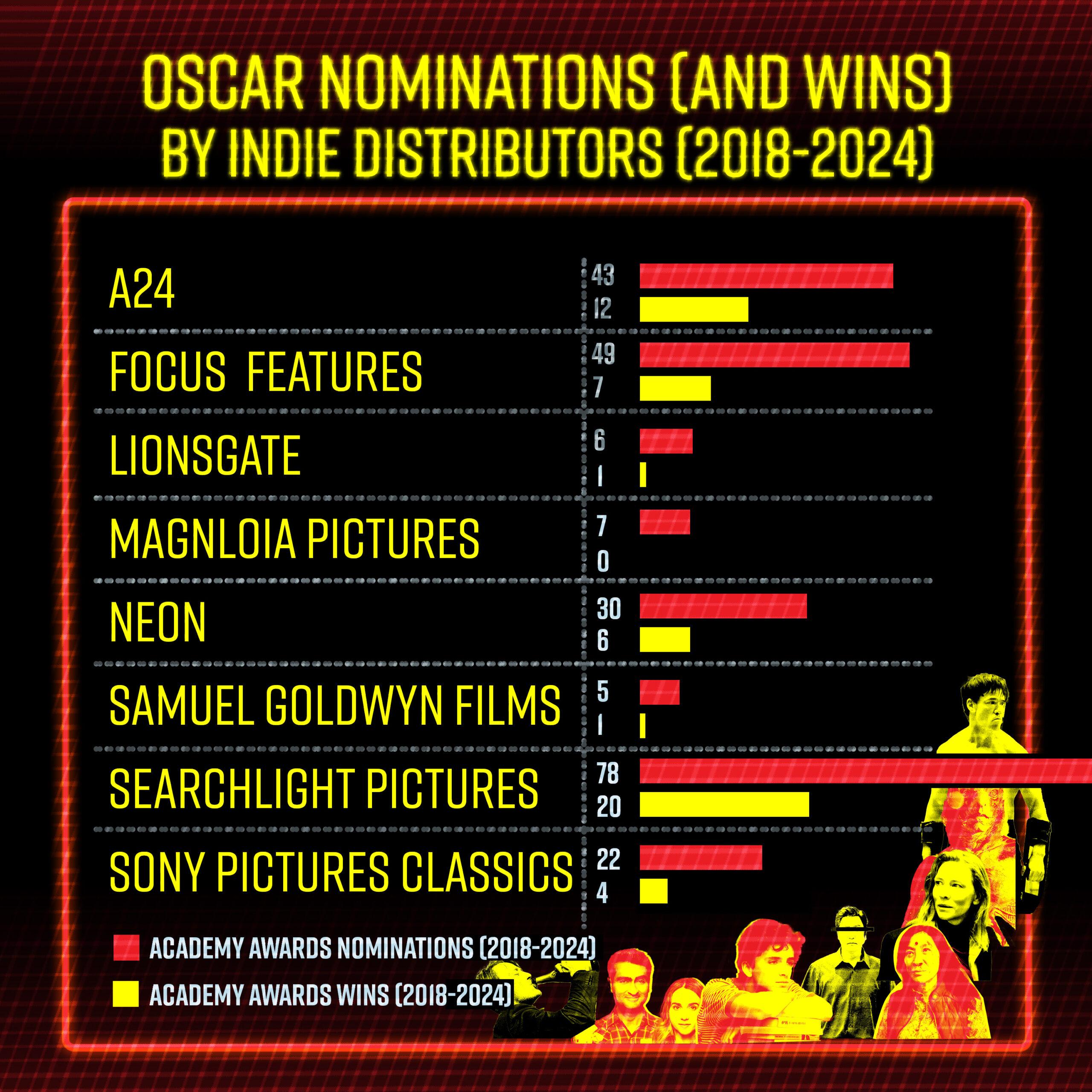

In 2024, Neon’s 15-film slate included Longlegs, the serial killer creep-out that took in almost $127 million worldwide at the box office, and the Sydney Sweeney-starring nun horror flick Immaculate—both of which surpassed their financial expectations. They also released Anora, the latest film from low-budget auteur Sean Baker. Anora became the fifth consecutive Neon movie to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, cementing an unrivaled and prestigious run. Since its release in October, Anora has remained a lead contender to win Best Picture at the Oscars, amidst challenges from Emilia Pérez, Wicked, The Brutalist, A Complete Unknown, and others. When the nominations are announced Thursday, Anora is also expected to be recognized in the categories of Best Director and Best Original Screenplay for Baker, Best Actress for Mikey Madison, and Best Supporting Actor for Yura Borisov and/or Mark Eydelshteyn. Additionally, Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig, another Neon release, was already shortlisted in the Best International Feature Film category and is predicted to be one of the final five nominees.

Soderbergh explains that he took Presence to Neon primarily because of the people who work there. “They were passionate in a way that gets you excited as a filmmaker,” he says. “They came to the first Sundance screening that was a Friday night, and when we spoke on a Zoom the following week, it turned out they were excited enough by the first screening to wrangle their way into a Saturday morning screening at 9:30 because they wanted to see the film again.”

This approach is typical for the 55-person company. “When we come into a screening, we roll deep—every department head is there,” says Tom Quinn, Neon’s co-founder and CEO. “When you get on that Zoom with us, we're making that decision there. The decision doesn't disappear into a black box or go through a morass of corporate red tape.”

During the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, it seemed like the crumbling indie film economy might never recover. Theaters were closing and the big studios were muscling into the day-and-date market out of desperation. And while those were certainly some dark times for the industry, Neon emerged as a trusted brand for a new generation of film brats whose education comes from Letterboxd recommendations, podcast picks, and a newly invigorated repertory house scene. Neon is a name they’ve come to count on, even if they don’t always know what type of film they’re going to get.

Presence will arrive in theaters on January 24. (Soderbergh’s 37th film, Black Bag, will be released by Focus Features less than two months later.) So far the filmmaker has been impressed with everything Neon has done during the lead-up. And unlike the give-everything-away-in-the-trailer tactic that’s become the default approach of many studios, Neon seems to trust that its followers will show up. “Neon’s whole attitude from the jump was, ‘We want to save all of it for when they come to the theater, so we’re selling a vibe, we’re selling your pedigree,’” Soderbergh says. “That’s unusual, and I think it comes from a place of confidence, as opposed to coming from a place of anxiety.”

It was an evening of streaming-choice paralysis that inspired Quinn to start Neon in February 2015. “I was sitting at home struggling to find anything to watch on either Netflix or Amazon,” he says. “I was stuck staring at the tiny sliver between the buttons for these two juggernaut streaming apps and thought, wouldn’t it be great to fill that space with the best cinema the world had to offer?”

It took him a little under two years to find the financing and eventually release Neon’s initial film, the toxic sci-fi comedy Colossal, in the spring of 2017. Quinn has 30 years of experience in indies and had built up lots of goodwill in the industry, having worked for Samuel Goldwyn Films, Magnolia Pictures, and Radius (a boutique label for the Weinstein Company), but Neon was his first attempt at starting his own stand-alone venture. According to Christina Zisa, Neon’s president of publicity, it began as a six-person team operating out of a WeWork on West Broadway in Manhattan. Most of Neon’s current department heads were part of this original group and several of them came over with Quinn from Radius.

“If you’ve heard Tom talk about movies for five minutes, it’s really hard to not get swept up in the passion that he has for films,” Zisa says. “If you’re going to follow someone into the fire of starting a company in this industry, why not make it the most excited person in the room who truly just loves the shit out of movies.”

(The other Neon cofounder is Tim League, the Texas-based figure originally behind the Alamo Drafthouse chain, Fantastic Fest, and the distribution company Drafthouse Films. In the early days, Drafthouse helped provide back office support for Neon and League is now a board member.)

Neon distributed eight films in 2017, striking a cultural nerve early with Ingrid Goes West. Their most impressive feat was landing I, Tonya at the Toronto International Film Festival, beating out competitors including Netflix, which was just beginning to express interest in awards aspirants. Neon’s minuscule team then pulled off an Oscar campaign in six months that resulted in three nominations and a Best Supporting Actress victory for Allison Janney. “It made us a company that people realized they had to take seriously,” Zisa says.

Key to Neon’s I, Tonya campaign was how it ignored some of the usual awards season rules. They introduced the film to the greater world with a red-band trailer that features Janney calling a parent “a cunt” in an ice rink full of kids within the first 45 seconds. “Everyone was like, this is an awards movie. Prestige! Prestige! You can't go out with a red-band trailer,” Zisa says. “And we're like, that's what this movie is. Why are we trying to change what the movie is? Let's celebrate what's on screen.”

Neon continued to expand, diversifying its offering with more international films and documentaries, including Three Identical Strangers and Honeyland, as well as bold-but-flawed selections like Harmony Korine’s The Beach Bum and Sam Levinson’s pre-Euphoria rampage Assassination Nation. Neon found its next landmark release in 2019 with Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite. The seventh film from the South Korean master would go on to win the Academy Award for Best Picture (making it the first non-English-language film to ever do so), as well as Best International Feature Film, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay. Parasite also helped normalize the idea that films and TV shows that aren’t in English can be mass-market entertainment in the United States. (You could argue the similarly anti-capitalist South Korean production Squid Game may not have crossed over without it.) “It's important for us to have an intent of not serving the traditional audience for specialized art films,” Quinn says. “These can be big movies, these can cross over. The idea that Parasite grossed $54 million [in the U.S.], well, that expands the border of what's possible.”

Neon’s momentum from both Parasite’s victories and the critical embrace of Portrait of a Lady on Fire crashed almost immediately into the realities of the pandemic. The film industry, which was already experiencing stagnant box office returns before the shutdowns, was thrown into further disarray as many small theaters closed for good and long-running chains faced possible bankruptcy. “Consolidation with the studios, battling streamers—the battle for hearts and minds has been so important and so aggressive over the course of the last five years. It's unlike anything that we've seen for decades prior,” says Christian Parkes, Neon’s chief marketing officer. “I'd held this belief that it's a war of attrition and whoever came out the other side still alive was going to be in the best position to actually be successful and to grow.”

During that brutal first year, Neon managed to have a hit with the comedy Palm Springs, thanks to their long-running streaming deal with Hulu. (The companies reportedly acquired the film at Sundance that January for $17,500,000.69, breaking the record for the largest purchase amount in the history of the festival by 69 cents.) As audiences were able to return to theaters in the ensuing years, Neon put out some of its best and most acclaimed projects, including The Worst Person in the World, Pig, Flee, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, and Anatomy of a Fall.

Still, it really was only until 2024—as more and more members of the public got back into the habit of going to theaters—that the money started trickling down to smaller movies. Coming out of the pandemic, a realistic prediction for a well-performing indie film would be to make $5 million, if that. In 2024, non-Neon pics The Bikeriders, Conclave, Nosferatu, We Live in Time, and the conservative hagiography Reagan were all bona fide hits that each made over $30 million globally. “You’re seeing these green shoots happen in independent film,” says Sean McNulty, the creator of The Wakeup newsletter at The Ankler. “I can’t tell you independent film is doing gangbusters. Most of them don’t make that much money. But now we’re at least starting to see things break through, where between 2021 and 2023 that was extremely rare.”

Neon’s Longlegs turned out to be the surprise hit of the summer. It was driven by an unnerving and atmospheric marketing campaign that consciously avoided showing Nicolas Cage, the film’s most famous star and titular villain. Key to its success was its ability to draw in younger viewers, who many in the movie business believed they had forever lost to TikTok and Twitch. “Longlegs did 75 million dollars [in the] U.S. this summer,” McNulty says. “That was not 50-year-olds going to see that movie.”

For decades, the art house market has typically skewed older, but the pandemic swapped the demographic trends. Viewers with either health concerns or who were exhausted by managing their children’s remote learning grew accustomed to waiting for titles to come to streamers or PVOD. Meanwhile, many college students and young adults who didn’t have anything to do while stuck inside used their free time to give themselves a cinematic education. “They’re like, ‘Shit, I’m going to go back through and see all these films that I never got a chance to see. This guy Akira Kurosawa, everyone says that he’s cool, so I’ll start burning my way through his films,’” Parkes says. “The emergence of a younger, more digitally active art house audience has just exploded.”

With their tastes broadened, these viewers don’t want to spend their time and money on normie fodder. “There is a general boredom with studio fare, which has become increasingly conservative and increasingly conventional,” Parkes says. So this audience is more primed for, say, a film like Anora—a nominal rom-com that features a not innately likable sex-worker protagonist, supporting actors pulled from the world of Russian cinema, nudity, commentary on the crushing nature of class inequality, and an emotionally devastating ending. Though Anora’s financial returns have been more modest than Longlegs, it did earn the highest per screen opening of 2024 and was Neon’s top-grossing film in limited release.

Having a viable Oscars contender like Anora can have many repercussions for Neon. As such, Zisa estimates that between August and March, awards campaigns take up 85 percent of her time. In terms of the potential financial results, she notes that Anatomy of a Fall, which received five Academy Awards nominations and won for Best Original Screenplay, made $5 million in the home entertainment market, the same amount it amassed during its U.S. theatrical release that began in October 2023.

This push can also have tremendous effects in terms of attracting talent and future projects. “When Oscar nominations come out, we're at Sundance,” Zisa says. “If we have nominations and then we're going into rooms and we're pitching movies to buy them later that day, who are you going to want to sell your movie to in that moment?”

As a relatively small company, however, Neon needs to be judicious about how it deploys resources and which films get this specific attention. “We’re not a Netflix who has $40 million to throw at an awards campaign,” Zisa says. “We have to be pretty concise and methodical about what we're doing and what we're choosing to support in that way because it is a huge financial undertaking.” This financial reality can cause friction. In December 2023, Neon released the Ava DuVernay film Origin. The movie’s official Twitter account (which has since been deleted) posted and reposted dozens of times about the lack of awards attention the film had received, putting the blame directly on a lack of effort by Neon and Quinn.

A robust Oscars campaign can be gruelling for its participants. Anora’s star, Madison, appears to be the contender from the film most likely to win an Academy Award, though she was recently eclipsed by Demi Moore in The Substance as the favorite after Moore’s victory at the Golden Globes. “[Madison] hasn't had a day off since August, literally since Telluride; she's maybe had a day or two off,” Zisa says during an interview in late November. “So I want to win, not just for ourselves because we like to win, but she is working really, really hard and deserves it. I want it for her more almost than I want it for the company.”

The filmmakers behind Anora decided to go with Neon because they knew that although the scale of their film was relatively modest, Neon could put it on the same level as movies with much more sizable budgets. “They were going to treat it like an event and make it feel important to see,” says Alex Coco, one of its producers. He also mentions that he still takes a picture of the film’s risque billboards on Sunset Boulevard every time he passes them “to cherish and remember that we had this for this window of time."

Parasite was previously Neon’s top-grossing film in the U.S., the winner of the Best Picture Academy Award, and the winner of the Best International Feature Film. Perhaps more notable is that in 2024, Neon released three different films that have or could find themselves in each of those three categories: Longlegs, Anora, and The Seed of the Sacred Fig, respectively.

As Osgood Perkins, the writer and director of Longlegs, notes in an email, “[Neon’s] just playing a different game than everyone else, a new kind of music for people’s weary and wary ears and eyes.”

Even if Neon is on the rise, it still is a distant second to A24 in terms of brand recognition in the contemporary indie film space. There aren’t Vox explainers about the Neon phenomenon or derisive comments about “Neon bros” yet. “Younger movie-goers, and certainly older ones too, know the A24 brand,” says Glenn Whipp, the Los Angeles Times film writer and columnist. “A lot of people will go to a movie just because it's A24. I don't think Neon has quite broken through in that way, but amongst cineastes or the Letterboxd crowd, for sure the Neon logo before a movie would get them into a film."

As A24’s status has grown, so has both the scale of its projects and the financial expectations for them. Of the company’s three biggest films at the box office in 2024, only the unsettling horror of Heretic seems obviously at home in their filmography. Civil War is a large-scale action movie and We Live in Time is a weepy romance with beloved young stars, though each does feature uncharacteristic flourishes for their genre.

The differences between the two companies’ output, however, may be more a matter of taste than resources. “Tom Quinn is just more adventurous,” Whipp says. “[Neon] has much more of a focus on documentaries and international film than A24. Those movies just aren't going to break through with movie-goers in a way that We Live in Time will.”

McNulty puts it another way. “[Neon] is more of a kookier uncle to A24,” he says. “It will probably go beyond what A24 will do in certain regards, maybe a little bit riskier. The size of their projects are not as large as A24 has gotten into of late—[A24] have a Timothée Chalamet movie, they have a Robert Pattinson movie, they're spending a good amount of money to work with the new A-list in Hollywood.”

Still, there is plenty of overlap between the two companies. Neon’s Immaculate is a religious-themed horror film with an ascendant female star—a microgenre in which A24 has excelled. And several directors behind Neon films previously made A24 movies, and vice versa. In fact, A24 released Red Rocket, Baker’s last film before Anora, while Neon did Vox Lux with Brady Corbet before he made The Brutalist, A24’s top Oscar contender. “How it's framed a lot, at least in film Twitter circles, is this A24-versus-Neon rivalry or competition,” says Graham Blackaby, the video essayist who releases pieces through his Captain Midnight channel on YouTube. “That's probably the wrong way to look at it, because I think they really, really need each other for a healthy American film industry right now.”

This past summer, A24 finished another round of investing and was reportedly given a valuation of $3.5 billion. At the end of November, Neon announced it reached a deal with Comerica Bank for up to $200 million in credit. In recent years, Neon has been able to take on a greater and earlier role in the production of many of its movies, so the company can rely less on just being the distributor of completed films. That means its slate isn’t at the mercy of whatever entrants make it into the film festival circuit each year. In the final months of 2024, filming began on I Love Boosters, Neon’s first film with director Boots Riley, which will be led by Keke Palmer and feature the resurgent Moore. Neon also recently announced that it will make Brides, its third film starring Maika Monroe, after Longlegs and the upcoming They Follow (the decade-later sequel to It Follows).

For Quinn, the real opposition for Neon has always been the streamers, which largely keep movies out of theaters and people in their homes, and have remained voracious in their amount of acquisitions. “Our largest competitor for the first five or six years of the company was Netflix, it was not other independent distributors,” he says. “I’ve talked about losing Hit Man, Richard Linklater’s film, to Netflix. It hurts. It’s tough. It’s tough for the marketplace itself. The idea that you’re losing one of these dominoes that is a great trailer target for other success. The in-theater experience and model is that all studios, all films cross-pollinate their success.”

As the marquee-conjuring name of the company suggests, one of the central tenets of Neon’s strategy is that nearly all of its movies get shown in theaters. Which, of course, runs counter to the economic trends of the times. “I can't say that this is a business plan that Wall Street gets excited about,” Quinn jokes.

In the spite of this reality, Neon’s in-theater emphasis does help them attract the people they want to work with. “They made 35-millimeter prints for Anora,” Coco says. “They made theater negative prints, beautiful prints, expensive prints, to take out around the U.S. All that stuff matters to us as the filmmakers, it matters to Sean, and it clearly matters to Neon.”

At times, Neon’s need to defy the current streaming-related ignominies in the film industry has led to some unexpected decisions. In 2023, the company paid STX Entertainment $15 million to distribute Michael Mann’s long-delayed biopic Ferrari in the United States. It subsequently underperformed at the box office and failed to get much awards recognition. “Obviously Michael Mann is an icon of cinema—I mean, a titan,” Quinn says. “The idea that a movie like Ferrari is somehow inconceivably available outside of the studio system and in danger of being relegated to a streaming premiere on Showtime, I feel that that's a great place for us to have impact and to step in and try to figure it out.”

For some, the importance of pushing against the streaming-first philosophy borders on existential. Perkins directed three films before Longlegs, including I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, which Netflix debuted in 2016. “I know I sound like some frothing crank on a street corner with a megaphone—streaming is the end of the world in terms of how movies are valued and loved and held in the firmament of eternal art,” he writes. “I think it’s different for episodic content, which is consumed differently, as something that is meant to pass one thing on to the next, but movies are meant to stay with you and streaming promises exactly what it sounds like. Streaming is built, at least it seems to me, on the notion that what comes next is more important than what is in front of you and so streamed movies are essentially not allowed to exist. Luca Guadagnino’s Suspira [which was released predominantly through Amazon Prime Video] is one of the best horror pictures in recent memory and no one knows it exists. With Neon, I had the remarkable good fortune to have my movie injected into the bloodstream of the culture where movies are meant to live.”

Perkins's next two films, including the Stephen King adaptation The Monkey that is coming in February, will be released through Neon.

When director Daniel Goldhaber was in the early stages of putting together his environmental thriller How to Blow Up a Pipeline, his dream was to shoot the movie at the end of 2021, premiere it at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2022, and then sell it to Neon. Which is exactly what happened. “We wrote a little roadmap and never again will I be so lucky for it to all work out that way,” he says.

Goldhaber believes that with the ongoing degradation or disappearance of institutions like local newspapers, assiduous film criticism, and independently owned theaters, viewers are in desperate need of discerning voices they can trust. “I became friends with the guy who worked at my local video store when I was 10 years old and he started recommending crazy stuff to me,” he says. “That’s who I had loyalty to.”

And in terms of potential replacements, for Goldhaber, the algorithmically created “For You” tab on a streamer isn’t just useless, it’s harmful. “It’s removing any sort of actual social relationship or context from finding work,” he says. “It makes the work less meaningful inherently.”

Talking about the importance of a strong brand identity can feel gross, but for Goldhaber, having the Neon name attached to a film has taken on a greater significance given the current entertainment climate. “We live in a moment where obviously curation is a dying art,” he says. “[Neon] are positioning themselves inside the culture as curators. That’s a complicated thing, but I do see it as something that is meaningfully helping to support movies that otherwise probably would fall through the cracks.”

When Quinn was still working in acquisitions for Magnolia Pictures in 2011, he went to a random screening of David Gelb’s Jiro Dreams of Sushi at the Berlin International Film Festival and ended up buying the movie. It did well, making over $2 million at the box office, which was extremely rare for a foreign-language documentary at the time. Yet it was the approach of the film’s subject, the at-the-time octogenarian sushi chef Jiro Ono, that was even more influential. “The thing that stuck with me was the idea of this restaurant, the significance of it, sitting inside of a subway station in a very humble setting,” Quinn says. “The prominence and impact of that restaurant with only 10 seats was global. Being one very specific thing and doing that one thing very well was more exciting and interesting than the idea of growing at all costs, of serving everybody.”

Given the breadth of the type of films that Neon releases, it isn’t intuitive that Neon does one very specific thing. Unless that one thing is to create a body of films that only makes sense for Neon. Many Neon films are divisive and hard sells, and a fair number of them don’t even break the $1 million mark. But each of them is a passion for at least one person inside the company who believes that the film has an audience, they just need to figure out how to find it. “What we’re doing is most important in the aggregate, that all these films together really can stand the test of time,” Quinn says.

Steven Soderbergh witnessed the thrilling days of indie film in the ’90s. During that era, the money could be great and the allure of fame was high, but as more tales and secrets from that time become illuminated, it’s clear just how vile it could be. In that context, maybe the limited possibilities of the modern indie era aren’t the worst. “Look, making a profit, winning a few awards, building a catalog that’s really valuable, and being able to feel good about what you do—if you want more than that, you’re pretty greedy,” Soderbergh says.

Hearing Soderbergh speak about the latest wave of indie film companies, it’s easy to recognize the similarities to his own approach as a filmmaker. It’s not a bad model to follow. “If your brand is that you are continually swimming upstream from shit that’s down the middle, there are endless opportunities to reinvent yourself,” Soderbergh says. “If you define yourself as being not the mainstream, you can always find a space to do something new.”