The Old Man and the Keys: The Improvised Legacy of Garth Hudson

Writer, musician, and Hold Steady member Franz Nicolay remembers the Band’s famed keyboardist and sage eccentric, who died Tuesday at age 87Garth Hudson wasn’t the most magnetic, the most handsome, or the most financially successful member of the Band—a group George Harrison, of all people, called “the best band in the history of the universe.” He didn’t sing or compose. Of the many words written about them, the fewest are devoted to him. He has the least screen time in The Last Waltz, the Martin Scorsese documentary of their final concert which cemented their mythology. His essentially settled and placid nature, and apparent lack of ego, made him a less obvious object of attention than the volatile and leonine Helm, the childlike Danko, the hapless Manuel, the canny Robertson. He mostly stayed out of the later Helm/Robertson blood feud. He passed through the Band’s narrative—their evolution from barnstorming bar band to super-sidemen to mystic mountain men to dissipated rock burnouts to ghost-band afterlife—seemingly unscathed, untouched by Helm’s bitterness or Manuel’s despair. He resisted, without visible effort, the chemical temptation that led to the band’s physical and musical decline. It made sense that he, the oldest member of the band, and Robertson, the youngest, would be the last ones standing—the latter ultimately protected from his indulgences by his savvy and practical-minded ambition; Hudson by his gently single-minded focus on perfecting the details of his musical vision. Meanwhile, his bandmates spoke of him with something like awe: “He could’ve been playing with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra or with Miles Davis,” said Robertson, “but he was with us, and we were lucky to have him.”

In his quiet way, it was Hudson—who died Tuesday at age 87—as much as any of them who made the Band sound the way they did, by expanding their harmonic palette as songwriters and their aural palette as arrangers, the ever-expanding breadth and depth of his musical reference—Anglican hymns, Bach, country polka, parlor song, jazz, R&B—broadening what had been a very good bar band into a group which, at its best, seemed capable of summoning the whole of American vernacular music. Band producer John Simon said of the group, “They were sometimes a single organism: Rick, the heart; Richard, the soul; Levon, the guts; Garth, the intellect”—but that “Garth was a universe unto himself.”

Eric Garth Hudson’s retelling of his childhood shares something with the imagined world of Charles Ives: the long tail of 19th-century America, an inventive but culturally conservative world of Protestant farmers, tinkerers, and brass-band fathers. Hudson was an only child, born in Windsor, Ontario, in 1937. Hudson’s parents, Olive and Fred, soon moved to London, Ontario—farther from the American border but, crucially, still within range of Detroit and Cleveland radio. His father and two uncles played drums and woodwinds in local dance bands. His mother’s Soprani accordion had pride of place next to their piano, and Garth eventually picked up both, along with his father’s saxophone. The Hudson family piano was a player model, so he both “heard and watched music being played.” (Not realizing that some of the rolls were four-hands arrangements led to some technical challenges as he tried to imitate them, a formative misunderstanding he shared with Art Tatum.) When he finally pieced together “Yankee Doodle,” his persistent playing annoyed his parents enough that they sent him down the street to his first piano teacher, Nellie Milligan, who drilled him in Carl Czerny and Florent Schmitt exercises and the sight-reading of hymn books. Eventually his parents sent him to Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music. But even as his technical capabilities—extraordinary by rock standards—made him a valuable commodity, he occasionally expressed a practice-room jock’s regret over the woodshedding he gave up: “I found out I could improvise; I probably found out too young,” he told Time magazine in 1970.

His practical training, though, was hardly limited to the classical canon. Two musical experiences in particular shaped his sensibility: Anglican church music, then American R&B and rock ’n’ roll. His first experience playing in public was as an accompanist at his uncle’s funeral parlor, where he assembled a repertoire of genteel and unpretentious Anglican and Baptist hymns. While church work encouraged Hudson’s dutiful and familial side, he had become aware of and fascinated by a more Dionysian outlet when he began, in the early ’50s, to listen to Alan Freed’s pioneering rock ’n’ roll radio show: “That’s when I realized there were people over there were having more fun than I was.” He hooked up with a rockabilly outfit, playing Little Richard covers at teen dances, backing touring acts (Bill Haley, Johnny Cash, the Everly Brothers), making the bar scene in Detroit, and recording a few singles as one of the few white acts on Detroit R&B imprints.

At this point he was still primarily a horn player, under the influence of hard-edged soloists like Clifford Scott. (The lineage of “the tenor saxophone from 1943 to 1958 in rhythm and blues and rock ’n’ roll,” as he put it with customary specificity, remained a Hudson fixation.) He was an awkward fit in the teeny-bop world—frontman Paul Hutchins remembered him as “very professional, with a strange, dry sense of humor”—though not quite the chaste, reserved figure he seemed in the context of the roistering Band. “He’d jump up and down while he played the accordion,” said Hutchins; and Hudson’s attraction to rock ’n’ roll was hardly monkish: “It all started with the reaction I got from girls because I was a musician. I thought if I could get that many girls phoning me up, I should really get into it.”

Hudson became, wrote Band biographer Barney Hoskyns, a “little legend” in the small world of Ontario rock, and was courted for poaching by Toronto rockabilly kings Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks—a mixed ensemble of Canadians and Americans that would, within a few years, evolve into the Band. For his part, Hudson was skeptical about a personality clash with the hedonist Hawks, and questioned whether he was suited for the pounding rock piano style: “I thought, I can’t play this music. I don’t have the left hand these guys do. … The whole thing was too loud, too fast, too violent for me.” Fortunately, the Hawks already had a piano player in the engine room: Richard Manuel said he played “rhythm piano,” which clarifies the general roles they would come to occupy: Manuel a heavy-pawed accompanist; Hudson the lead player, a spiralling melodist.

There were two roadblocks. The first was Olive and Fred Hudson, who feared that joining a touring rock outfit would be a squandering of their son’s training. (“Unfortunately,” Garth deadpanned, “in order to become acquainted with the idiom of rock ’n’ roll music it is occasionally necessary to play in a bar.”) Hawkins, a charismatic performer with unlimited faith in his own charm, made a pilgrimage to the Hudson household. As the oft-told story goes, he convinced them that the band would be hiring Garth not just as keyboardist, but as a music teacher for the other members—at an extra $10 a week. In practice, these “lessons” were more suggestions than organized instruction—bassist Rick Danko, for one, groused at the idea of practicing scales. Essentially he expanded the band’s harmonic vocabulary. “Garth showed us some shortcuts to more sophisticated chord progressions,” wrote guitarist Robbie Robertson in his memoir. “When we were practicing or learning some new songs, we’d get stuck and we’d say, ‘Hey Garth. How do we do this?’ He’d always have the answer.” His sax playing gave the group a professional sheen and, Helm wrote, “a soul-band horn section when we needed one,” moving the Hawks “toward a more R&B feel from the rockabilly we’d been playing.”

But first, the Hawks had to buy him his dream Lowrey Festival organ, which offered him pitch-bend effects and an old-timey, pump-organ affect. Hudson wanted to avoid the Hammond organ clichés which were already endemic: “He wanted to be Garth Hudson, not a Jimmy Smith,” said Hawkins, referring to the jazz organist who helped popularize the hegemonic Hammond. “It took us six months to save up enough money to buy the Lowrey organ,” said Rick Danko; but once they had, the lineup of what eventually became the Band—a slick social climber, three good-time Charlies, and a genius—was set.

Hudson was, indeed, an unusual fit for the Hawks. He “spoke seriously and deliberately,” said Helm, “and whored around less than us.” For someone who had been in rock bands since his teen years, Hudson was a restrained presence in that louche era: “Groupies don’t come up to me because I’m the old man,” said Hudson (who ranged from three to six years older than the rest of the group). “It’s usually too much hassle. Unless, of course, it’s a day of spring in the middle of winter, but those chicks—it’s just not real. God bless them just the same.” Jonathan Taplin, the Band’s former road manager, put it more simply: “Garth was not an orgy guy,” he told the podcast The Band: A History in 2021.

Hudson was generally spared the armchair diagnoses that might accompany a shy eccentric with obsessive tendencies. He spoke elliptically, in a free-associative monotone croak (one writer referred to “the oddly measured, august cadence of a 19th-century scholar”) with a lateral lisp that became more pronounced as he aged. He was euphemistically referred to as odd, or private, or “in another world.” His bandmates talked about him as a kind of holy fool—sweet, acquiescent, humble, accommodating, and disassociated (Helm, in particular, took a protective, motherly tone about him). “He had narcolepsy and could fall asleep at any time,” wrote Robertson. “He claimed he didn’t sweat, no matter how hot it got. He would buy orange juice but wait for two days to drink it until all the pulp had sunk to the bottom. He would eat around the seeds of a tomato.” Interviewers had to adjust to his deliberate pacing, to gnomic digression and an aversion to emotional introspection. His memory of The Last Waltz focuses on details of a malfunctioning Leslie speaker; his recollections of the Music From Big Pink period involve domestic arrangements—“Richard did the cooking, I did the vacuuming.” He was unaffected by the drugs and paranoia of the tours with Bob Dylan—“You get up in the morning and mow the lawn, or you get up on stage and get booed. What’s the difference?” The sentimental power of music amounted, it sometimes appeared, to just another technical challenge: He told Danko that when playing at his uncle’s funeral parlor, “he’d just listen to the eulogy. And when it was time to push the buttons that made people cry, he would push those buttons.”

The Band’s rustic image was always a bit of a put-on—these were, after all, ’70s rock stars, with all the womanizing and indulgence that implies. But Hudson embraced the identity of hillbilly oddball with gusto and evident sincerity: He grew out his beard, took up pipe-smoking, trucker caps, and the wide-brimmed, Amish-style hats that became his signature performance attire in later years. He collected guns and knives—even molding his own bullets. He settled in the hamlet of Glenford, New York, worked on building his house, and taught Helm how to dowse for water with a bent stick. “I’ll never forget,” said Helm’s ex-partner Libby Titus, “seeing him skin a deer that had been hit in the road” by the glow of Helm’s headlights.

Rock writer Ralph J. Gleason called him “the first organ player since Fats Waller with a sense of humor,” and his droll wit was underrated by people who thought him, perhaps, a bit simple. He described touring as a series of chairs: “First, you get in a car and go somewhere to sit and wait in someone’s living room. Then you all go to a meeting place and sit and wait. … There are about 80 chairs in a weekend. If you do it in different weekends there are 240 different chairs in a row.” When the Band was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, he stepped up to the podium and announced, “This’ll be short and sweet,” before spending several minutes listing obscure names from the band’s past—Thumbs Carllile?—and giving a short lecture on tenor sax players from the early rock period, as Danko and Robertson looked on, bemused.

For all his deflection and diplomacy, he could occasionally let slip an opinion on Band dynamics. When Robertson, in an interview, seemed to diminish Hudson’s role in songwriting—“with Garth, every time we sat down it was like a musical journey into the cosmos … Beautiful stuff came out of it, but no defined structures, nothing I could repeat or build upon”—Hudson pushed back in his understated way: “Now as then, I provided and placed a thesaurus of melodies for the writer to capture.” (What this meant in practice can perhaps be seen in another Robertson quote: “If I was trying to do a song that was on the verge of being a little more sophisticated than what we normally did, Garth would help me [complete] the chord structures.”) His doggedly literal-minded answers to interviewers provided an implicit contrast to Robertson’s pompous self-mythologizing. And he seemed to endorse a criticism sometimes leveled at the Band, that their vaunted democratic ethos which rejected having a designated “frontman” also exposed a kind of weakness in a group which had, after all, spent the bulk of its career as a backing group. Contemporary reports sometimes criticized the Band as alienating and inward-looking on stage without a welcoming or focusing presence at the center. “That one feature we did really well,” Hudson once said, was “accompanying a singer.”

But it was the piano and organ doubling of Hudson and Manuel that was the foundation of what became the Band sound—“that’s what we built on,” said Helm; Robertson called the instrumentation “secure.” The piano/organ combo was familiar in late ’50s gospel music—Hudson pointed to the Caravans’ “To Who Shall I Turn” as a model—and proved immensely influential, notably in the E Street Band. (Roy Bittan’s piano melodies in right-hand octaves share more than a little DNA with Hudson’s fills in, for example, “The Weight.”) Hudson took his role as aural set designer seriously, “considering the meaning of the words, and the time period” in which the song took place. The group nicknamed him H.B., for “Honey Boy,” because, said Helm, “at the end of the day … Garth was still in the studio sweetening the tracks, stacking up those chords … whatever was needed to make that music sing.”

His drive for novelty was powered by his technical proficiency—Taplin called him “a born tinkerer.” Hudson was the de facto engineer of the so-called “Basement Tapes,” recording experiments, sketches, and publishing demos with the Band and Bob Dylan (as well as a group called the Bengali Bauls) in their cinder-block basement with a pair of microphones perched atop the hot-water heater. (Hudson made a rare vocal appearance in a Basement Tape recitation called “Even If She Looks Like a Pig.”) He built a pipe organ in his shed. He was, said Danko, “interested in Scriabin around then,” and the possibilities of synesthesia. In the studio for the Band’s debut album, he put his organ speakers in a booth against the wall, so he could overdrive them while still getting a muffled tone he liked. He triggered a Rocksichord with a telegraph key for a special effect in “This Wheel’s on Fire.” He played the weeping, harmonica-like melodica in the verses of “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” with the instrument wedged against one leg while playing the Lowrey with the other hand (“kinda tricky”). He rigged up a talk box for Helm on their cover of “Ain’t Got No Home.” And, on “Up on Cripple Creek,” he innovated the use of the wah-wah pedal on a Clavinet, for a jaws-harp effect that was picked up by Stevie Wonder for “Superstition” and became a key trope in funk. “Some people want to know how a watch works,” said Robertson, “and other people just want to know what time it is”—Hudson was emphatically the former.

It is perhaps worth pondering for a moment Hudson’s contribution to the whiteness of the group. Not as a pejorative—although Ta-Nehisi Coates has written about his visceral reaction against “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” calling it “the blues of Pharaoh”—but as a sonic marker of (mostly) working-class identity. When the band was trying to choose a name to go on their record contract, they seriously considered calling themselves the Crackers or the Honkies. Their homespun image, which was a crucial element of the evolution of the vague genre of “Americana,” was one of rural whiteness: the Scotch Irish whiteness of Appalachia, the proletarian English whiteness of the South, and the contested whiteness of the francophone Acadians (Americanized to “cajuns”) who connected Helm’s deep Southern heritage to that of his Canadian bandmates. Hudson was capable of the funky Clavinet that inspired Stevie Wonder, but also of what Greil Marcus once called “the whitest organ playing imaginable—circa 1900 Episcopal funeral music so palely genteel it could lighten the skin of the janitor.” His chosen instrument was not the gospel-associated B3, but the more Victorian-domestic Lowrey; his church music not gospel but Anglican; his musical core not the soul of Ray Charles and Bobby “Blue” Bland that animated Manuel or the devotion to the blues of Muddy Waters and Sonny Boy Williamson that leavened Helm’s redneck affect—instead, it was Bach. The mythos Robertson created owed a great deal to Helm’s Southern upbringing, but also to Hudson’s aural evocations of the minstrel and medicine shows, the shape-note singers and hillbilly squeezeboxers, the pre-rock sonic popular detritus of white North America.

Hudson became a more prominent part of the Band sound as the group’s recording career stumbled along, if only because he and Robertson were the members who could be relied on to turn up for work. When the group relocated to Malibu in the 1970s, Hudson had the time, budget, and space to experiment with new synthesizer technology, enlivening the Band’s lackluster latter-day records. By the late-career highlight Northern Lights–Southern Cross, Greil Marcus wrote, “he wrap[ped] his sound around the Band, enfolding their performance with a warmth of spirit.”

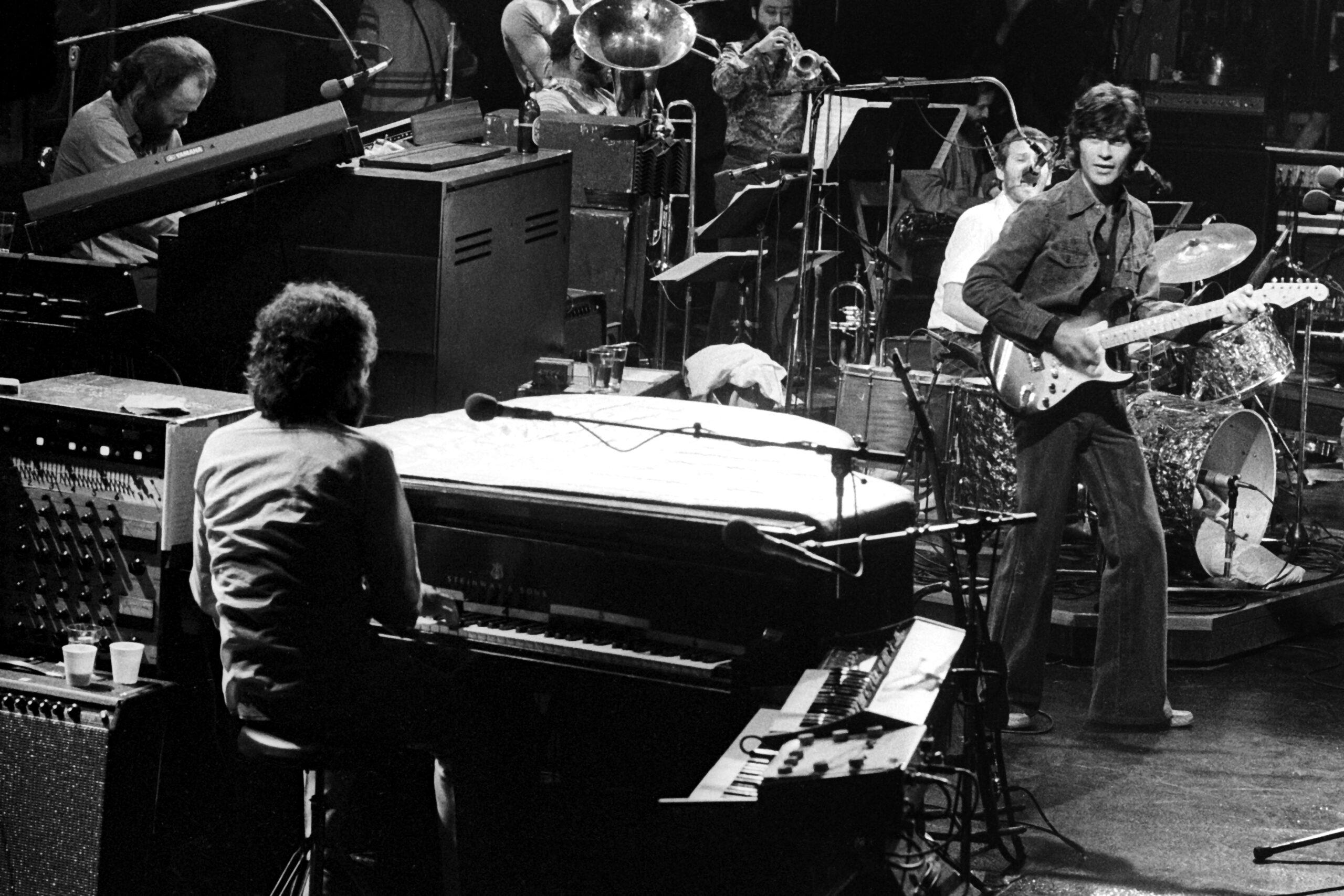

Like his bandmates, the press had a tendency to exoticise Hudson with a mix of bewilderment and veneration: “a bearded, big-browed Thor in the back,” “a combination of Beethoven and U.S. Grant,” “one part Rick Wakeman and one part Civil War … more peculiar than persuasive.” Time, in its 1970 cover story on the Band, called him “beyond question the most brilliant organist in the rock world … a predictable surprise, [like] a cuckoo from a cuckoo clock.” His signature showcase was an extended improvisation, usually culminating in the organ riff to “Chest Fever,” which the group came to call “The Genetic Method” (after a book of speculative ethnomusicology Hudson had been reading).

In a famous incident, the Band’s set at Watkins Glen (for a then-record crowd of 600,000) was interrupted by rain. The group had left the stage, but as Helm tells it, “Garth has a couple of sociable pulls on this whiskey his homeboy has, and all of a sudden the roadies are shouting and scrambling, and Garth climbs into his organ seat and starts to play by himself. It was extra-classic Hudsonia: hymnody, shape-note singing, gospel, J.S. Bach, Art Tatum, Slim Gaillard … the rain petered out. Just like that. It seemed clear to me that master dowser Garth had stopped the rain.” In post-Band years, these improvisations would move to piano, and integrate new enthusiasms—cocktail jazz, Stephen Foster, Leo Ferre, Hawaiian music, norteño, Eastern European accordion. Not infrequently, he offered them to interviewers in lieu of verbal answers. It seemed to be the way he preferred to communicate, to illuminate his interests and the musical connections he intuited directly, by example.

His participation was crucial to the reunited Band tours of the ’80s, when the musicianship of his compatriots (sans Robertson) had begun to deteriorate. Though he joined the reconstituted group—he needed the money, among other things—Garth said touring hurt his technique: “I had a considerable piano technique built up. … But when I got on the road, I lost it.” He was typically unsentimental about his recorded legacy with the Band. In 2010, he said he hadn’t listened to Band records for years. When he did, his review was, simply, “I was satisfied that I had done my job, that I fulfilled the role.”

Hudson spent the decades following The Last Waltz on a steady string of sessions. A certain lore has evolved around his magical in-studio ability to assemble a part from multiple overdubs. This trope is encapsulated by Mercury Rev’s Grasshopper in Barney Hoskyns’s Small Town Talk: “He’d bring out one horn and play a few notes, and then he’d play another horn and play some notes. It was all in his head. And after an hour, all the parts fit together into this melody line. We were flabbergasted. It was like, ‘How did he do that?’” (Artie Traum’s twist: “My fondest memory is watching [Garth] cut a track and before listening back say, ‘You know the 22nd measure, third note? Take that out.’”) But there may be an aspect of wishfully affectionate mythmaking in play. An acquaintance told me a story of friends of his who hired Hudson to play on their children's record: “He came in and recorded a track on accordion, then asked to overdub another, and another, and another. When all four were done he asked for playback. It sounded awful; and he just laughed and said, ‘Sometimes I get lucky.’”

But his bank account didn’t grow at the rate of his discography. Despite the resumption of Band touring, Hudson suffered three bankruptcies, the loss to fire of his Malibu ranch, and the theft of many of his golden-years instruments from a storage space. In 2013, the contents of another loft in Kingston, New York—which he rented after his house was foreclosed on—were auctioned off after seven years and a reported $60,000 in unpaid rent, after what The New York Times called “years of unanswered correspondence, a second eviction in 2010, and an unsuccessful attempt to coordinate a fundraiser for Mr. Hudson with other Band members.” (Rolling Stone added that the stash apparently included an uncashed royalty check from 1979 to the tune of $26,000.) He, along with Danko and Manuel, sold his share of the Band’s publishing and legacy to Robertson, saying only, “The deal was made. It was a good job. And I got out of it alive.”

The one thing Hudson didn’t do was release music under his own name. “I’ve never seen someone more able, and less willing, to take the spotlight,” said producer Janine Nichols. His jammy solo debut The Sea to the North (2001) exists in two versions, the second a “Collector’s Edition” for some reason re-ordered and shortened. Probably the best available distillation of Hudson’s live appearances and his unfiltered aesthetic—improvisations, selected classic Band songs, hymns and Balkan accordion, and eclectic covers—is Live at the Wolf, credited to Garth and Maud Hudson.

Garth met Sister Maud—as he liked to call her—around 1978, shortly after The Last Waltz, when the former Maud Kegel was singing on a Hirth Martinez session that Robertson was producing. The two got together, and until her death in 2022, she remained a constant presence in Garth’s life, as not only his wife, but a gatekeeper, publicist, manager, and collaborator. “We’re both old-fashioned,” Maud said of their long marriage. The couple were nocturnal—playing music, listening to college radio (he taped and catalogued the polka/norteno show on SUNY New Paltz’s WFNP), meeting journalists for 3 a.m. interviews at all-night Kingston diners—retiring each morning just after sunrise.

I should admit to a deep bias toward Garth Hudson. My own encounter with The Basement Tapes as a teenager was transformative. It made me pick up my father’s accordion (Hudson was the lone advocate from the rock world for the accordion during its long cultural eclipse), and the hobo-formal vision of the Band in Elliott Landy’s sepia photographs directed me toward a stage attire that I could adopt just as well as a 20-year-old and as a middle-aged man. I finally got to see him at what was aspirationally billed as a “festival” in the fall of 2016, on a farm in the eastern Hudson Valley. A few dozen people huddled under a drink tent, sheltered from the cold rain, a hundred yards from the small stage where Hudson, shrunken and bent, shuffled around his keyboards, slowly plugging in cables. He worked his way through a 45-minute set of his signature improvisations while cycling through keyboard presets. I noticed the lack of festival-style fencing or any security and decided to take the opportunity to introduce myself to my hero.

Some helpers were loading Hudson’s gear into a battered white minivan. Maud sat on a bench seat. I lurked awkwardly, looking for an opening. Hudson was in the passenger seat in his long black coat and wide-brimmed hat. I said something generic, that I was a big fan and a piano player. “Oh yes?” he said. “What piano players do you like?”

For some reason, the only name I could come up with in the moment was Art Tatum. Hudson recoiled. “I don’t recommend Art Tatum for young players,” he said sternly. “Start with Johnnie Johnson and montunos.”

I asked if I could take a picture with him, but he had embarked on a lecture. I tried to listen while surreptitiously snapping a photo of the two of us in the low light, suppressing a twinge of guilt at my own frivolousness. A handler said it was time to go, I thanked him, and that was that.

I’m tempted to simply execute a notebook dump, in the name of corralling all known Garthiana in one place: how he advocated for jazz saxophonist Ben Webster to open for the Band in Hamburg in 1971. How he often played shoeless, or barefoot. How, when asked to describe himself in one word, he chose “eager,” and when asked what song he’s most proud of he named one that didn’t exist. How his five favorite records, he said, were The Best of Spike Jones, Leona Anderson’s Music to Suffer By, The Four Freshmen Live, Johnny Hodges With Wild Bill Davis, and Primus. His favorite musician? “Me.”

Hudson was one of those people who finally achieved their apotheosis, or seemed to settle into their proper form, as an old man—a gnome obscured behind an accordion, an ancient mariner with a shrunken carved-apple face. It made sense that he would identify Chuck Berry’s pianist Johnnie Johnson as a foundational player. In a way, Johnson was Hudson’s nearest precursor in reinventing the role of keyboardist in a rock band: not a self-accompanying frontman like Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, and the other early rock pianists, but an inventive and invaluable sideman. Hudson’s two-handed agility was rare, and his inadvertent, antiquarian charisma—“less a mad professor,” said John Simon, “than a very dedicated pedant”—and appropriately old-fashioned name made him more memorable than the next generation of ’70s virtuosos. For such a restrained and rooted person, Hudson’s playing was notably restless and overflowing, constantly swirling on multiple fronts: the woozy pitch slippage of his carnivalesque organ, the accelerating and slowing Leslie and chorus settings, the overflowing fills and stuttering octaves that poked through the spaces between the end of each vocal line and the beginning of the next, never quite the same shape or rhythmic pattern or even sound. To picture Hudson in flight is to picture precarious organs and synths stacked on each other—a rickety fortress almost completely enclosing Hudson—on a festival stage, where he reaches for them, eyes closed, in turn, never settling on a tone for more than a phrase or two, always in the process of approaching or leaving or decorating a chord tone with grace notes, passing tones, mordants, and appoggiatura, snakelike chromatic obbligati, circling without resolving, flashy but nonchalant: Hoskyns called it “inspired noodling;” Hudson called them his “rotlings.” Even the clavinet bass in “Up on Cripple Creek”—a single repeated note—gets played by multiple fingers in turn, and morphed and twisted by the wah pedal.

Hudson’s anchorite, inward-looking devotion to the study and pedagogy of music undermined the truism of the naïve rock performer, the inspired noble savage. “Most of [the learning process] is supposed to be a secret,” he said in one interview, while playing through Hanon piano exercises. “You’re supposed to jump off the turnip truck and grab an axe and perform.” He was neither rebellious nor dissolute. But he drew on as deep a well of musical vocabulary, and the curiosity that engendered it, as any musician in the rock canon. “The way Bob [Dylan] was Shakespeare compared to all the other songwriters,” said Al Kooper, “Garth was the Shakespeare of the organ.” The analogy is perhaps less hyperbolic than it appears. Hudson, too, assimilated a vast array of (musical) language, from the vernacular to the elite, into a deeply referential but unmistakably personal and original idiolect. That he deployed it in the service, mostly, of other peoples’ songs and under their names is no diminishment, and is perhaps to his credit. His self-effacing, autodidactic virtuosity wasn’t in the service of ego, but—like an anonymous monk copying and illuminating a manuscript toward the furtherance of human knowledge and the glory of God, while adding his errata, inside jokes, and graffiti in the margins—in the awe of the bottomless wonder of human musical expression.