The Evolution of the NFL Play Calling Network

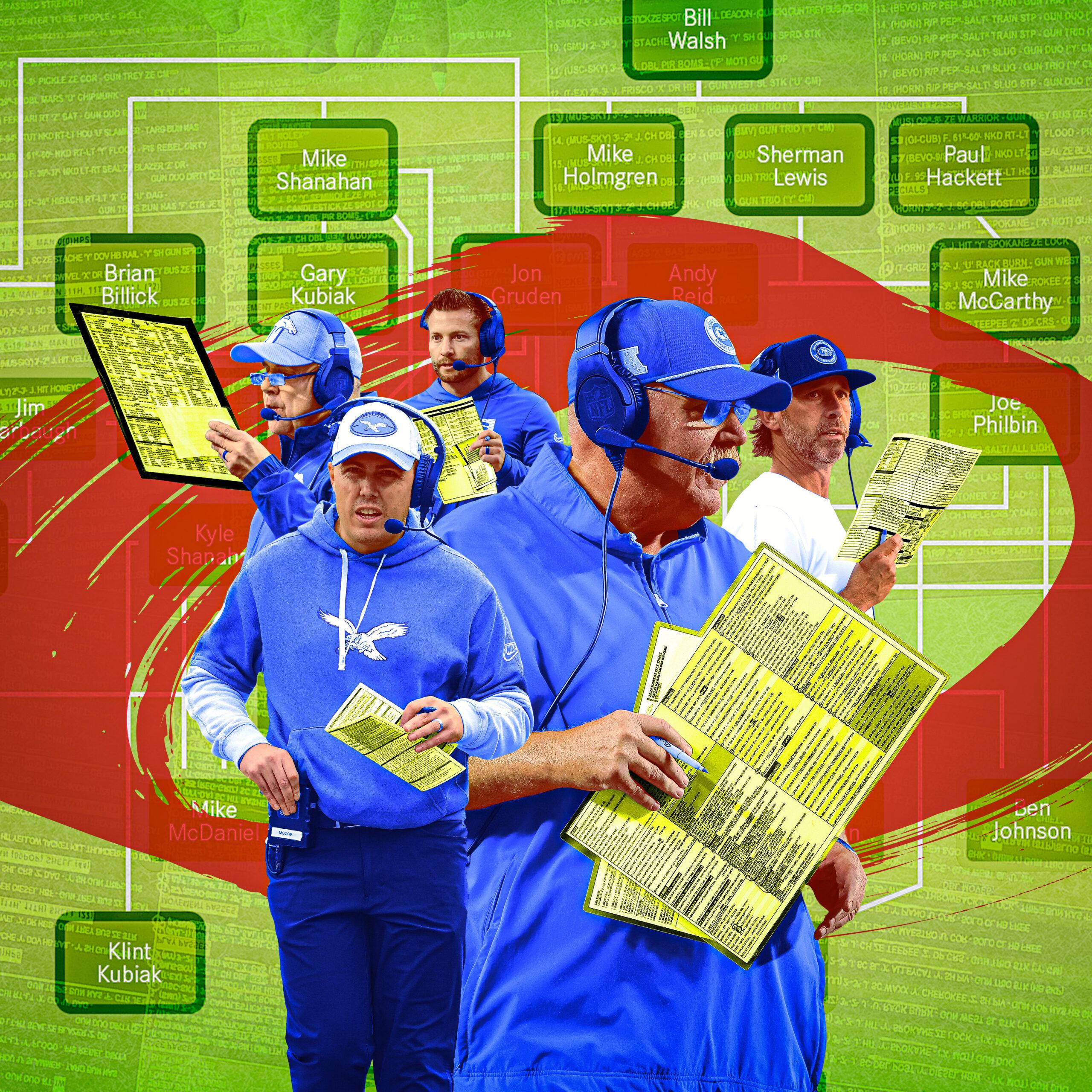

Kyle Shanahan and Sean McVay reshaped the modern coaching landscape—but now a new group of young play callers is starting to emerge. By looking back at how the dominant offensive trends of today were formed, we can see where that new group will take play calling in the future.

If at any given moment you polled 32 NFL head coaches about the importance of play calling, you’d likely get 32 different answers. You might expect Dolphins coach Mike McDaniel, who’s earned a reputation as one of the league’s most innovative play callers during his three seasons in Miami, to fall on the side that considers it a vitally important process. After all, he worked with Kyle Shanahan, Sean McVay, and Matt LaFleur in Washington during the early 2010s and served as Shanahan’s offensive coordinator in San Francisco—and, as such, is a prominent member of the modern league’s most dominant coaching tree, which has produced some of its best play callers. McDaniel has even held on to play calling duties (stubbornly, some might say) throughout his tenure as Dolphins head coach. But the 41-year-old doesn’t appear to have the same reverence for the process that some of his coaching buddies do.

“I think it’s pretty asinine when coaches think they win or lose games, and I think that most of the play callers think their play calls win or lose games,” McDaniel said on the Playcallers podcast in 2023. “That’s cool and all, but I don’t understand how you can overweigh your contribution to the team when you’ve had so many examples of calling a trash play and it works—or calling the perfect play and it doesn’t work.”

He continued, “All these things, so many people involved—how shortsighted and egotistical [or] dumb is it to sit there and act like your play call wins or loses the game?”

McDaniel may not consider play calling the be-all and end-all of coaching, but the league’s recent hiring practices would suggest most teams think otherwise. From 2017 to 2024, NFL teams hired 53 head coaches. Of the 33 with a background in offense, 23 had play calling experience. In this year’s hiring cycle, three of the six open jobs have gone to candidates who have called offensive plays. And that number could increase, as Eagles offensive coordinator Kellen Moore is currently seen as the favorite to land the Saints job. If Moore gets the gig, over half of the league’s head coaches will double as their team’s offensive play caller.

This trend started around the rise of McVay and Shanahan in 2017. They earned head coaching opportunities after successful stints as play callers in Washington and Atlanta, respectively. Shanahan needed a couple of years to elevate the 49ers offense. But McVay found instant success with the Rams—winning the NFC West in his first season, crafting the league’s highest-scoring offense, and inspiring teams to hire play calling head coaches. That offseason, four franchises hired head coaches who would also call plays on the offensive side of the ball, increasing the number in the league at the time to 14. A 2018 ESPN article described that shift as an attempt to find “the next McVay.” “Traditionally, NFL owners have wanted a head coach to act as a CEO for the football side of the organization,” the article read. “However, with the intense focus on the quarterback position and with playcalling being such an important part of game days, former offensive coordinators are choosing to continue doing what they are best at: calling plays.”

After McVay led the Rams to a Super Bowl appearance in his second season, the “Sean McVay effect,” which now has its own page on Wikipedia, officially took hold of the league, and anyone with even a slight connection to the Rams coach seemed to garner consideration for a head coaching job. The Bengals hired Zac Taylor, then McVay’s quarterbacks coach, as their head coach. LaFleur, McVay’s first offensive coordinator in Los Angeles, was hired by the Packers after one season calling plays for the Titans. And after the Cardinals hired Kliff Kingsbury from the college ranks, an article on the team website listed “friends with Rams coach Sean McVay” as a part of his résumé. It was later removed after being widely mocked across the internet.

After the league was done raiding McVay’s staff for offensive assistants, it turned its collective attention to Shanahan’s staff in San Francisco. LaFleur could also count as a Shanahan assistant after serving as his quarterbacks coach in Atlanta. And McDaniel spent one season as the 49ers’ offensive coordinator before getting the call from Miami. Today, 11 of the league’s offensive play callers have direct connections to Shanahan and/or McVay.

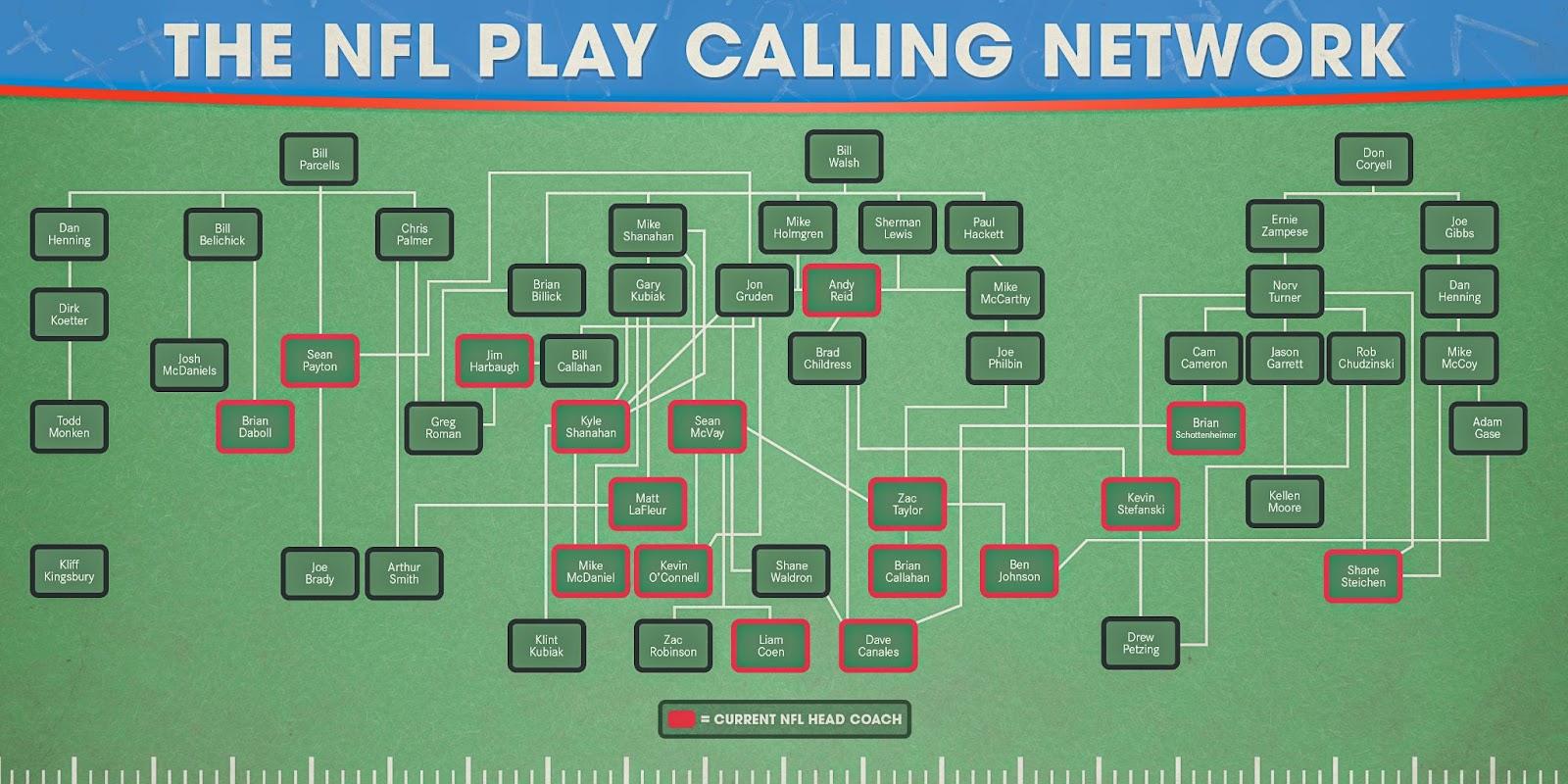

It’s shocking how quickly the McVay/Shanahan tree has spread throughout the past half decade, but if you take a step back to get a wider view of the NFL’s network of play callers, you’ll find that the “McVay effect” isn’t some isolated phenomenon. It’s the next phase in a process that started with Bill Walsh’s 49ers in the 1980s and was accelerated by the success of Mike Holmgren’s Packers and Mike Shanahan’s Broncos in the 1990s.

The elder Shanahan served as the 49ers’ offensive coordinator from 1992 to 1994, a few years after Walsh left San Francisco, but he didn’t change the offense and said the coaching materials Walsh left behind were vital to his development as a play caller. Shanahan continued running the West Coast offense in Denver, where he and offensive line coach Alex Gibbs meshed the passing game scheme with a run scheme that was built around zone blocking. That combination still serves as the foundation of Kyle Shanahan’s offense today.

Similar processes were taking place on other branches of the Walsh tree. Holmgren put together a legendary offensive staff in Green Bay, comprising eight future head coaches, including Jon Gruden, Andy Reid, Steve Mariucci, and Mike Sherman. That group expanded Walsh’s original playbook as far as their imaginations allowed.

"That started with Paul Brown and Sid Gillman,” Holmgren said in 2013. “Bill [Walsh] was an assistant coach and the [play]book kept getting bigger and bigger. I got to the 49ers, then you take it, then I take it to Green Bay, then Andy Reid and Steve Mariucci and Gruden they take it to their respective teams. And then you have creative young coaches throwing ideas on the table so you add this page and add this page.”

Those early innovators put their stamp on the West Coast offense, and their successes empowered their young assistants to do the same once they got bigger jobs with new teams. And now, while Kyle Shanahan and McVay have certainly reshaped the NFL’s modern coaching landscape, they’re also viewed as veterans—with the next group of young play callers starting to emerge. By looking back at how the dominant offensive trends of today were formed, we can get a better idea of where that new group will take play calling in the future.

McVay and Shanahan may be the rock stars of the NFL play calling landscape right now, but Reid has seniority and more rings than those two combined. He was also one of the key figures in the modernization of the West Coast offense—a process that started before he took over as Eagles head coach in 1999. Reid’s system is the ultimate manifestation of the air raid—a concept explained in detail in S.C. Gwynne’s book The Perfect Pass. It relies on simple concepts run at high volumes in order to ease the learning process for players and maximize efficiency.

Reid first encountered the system at BYU in the late ’70s, playing for LaVell Edwards, the coach who inspired the philosophies of the air raid. And once in the NFL, Reid learned the proper West Coast offense under Holmgren in Green Bay and sought to balance the principles of a timing- and precision-based passing game with a college-esque spread presentation. That began in earnest in Philadelphia, where he coached the NFL’s most dynamic skill-position group, made up of DeSean Jackson, Jeremy Maclin, and LeSean McCoy. The run game was efficient, the ball got out of his quarterback’s hands quickly, and if his quarterback did hold on a little longer, that probably meant a big play was coming.

Fifteen years later, Reid has those same concepts humming in Kansas City—and he has the most talented quarterback in football history at the center of it all. The offense hasn’t just incorporated the run-pass option: It’s damn near mastered it. And it’s done so by welding old-school quick passing concepts onto a shotgun-based rushing attack.

Whether defenses want to play conservatively, load up the box, or blitz Reid’s offense, he doesn’t have to overload the quarterback with multiple play calls to check into at the line of scrimmage. The answer to any defensive look is usually baked into the design of the play, like the example above, where the Chiefs are running power with a hitch route attached. This is the ultimate look into how Reid’s offense puts you in a bind: With the defense deploying two safeties deep, there aren’t enough bodies in the box to take away space between the tackles. But if the defense opted to load up or blitz, it’d be left susceptible to an easy completion on the perimeter.

Oftentimes, all defenses can do is play man coverage to try to take away space, and that’s where Reid’s dropback passing game best reflects both the simplicity of the air raid and the versatility of the West Coast offense. When you watch the combination of clips below, you’ll note that the formation is the same throughout and that the passing concepts are relatively basic progressions, but there are different players with different skill sets in different spots in each clip.

Defenses can scheme up answers for some routes—at the expense of opening up space for others—but receivers are equipped with small ways to adjust their routes based on where there’s open grass. The onus to find the holes in coverage falls on the quarterback. Because this offense’s foundation is built on conceptual mastery instead of rote memorization, limited quarterbacks can have a hard time maximizing this scheme—and less talented coaches have difficulty installing it. As it stands right now, no offensive play callers outside of Kansas City have coached directly under Reid in this century—and it’s likely that his unique spin on the West Coast offense will leave the league whenever he retires.

Because of that, while Reid might be the most successful former Holmgren assistant, he’s not the most influential. That would be Gruden, who not only gave Shanahan and McVay their first NFL coaching jobs but also brought Sean Payton into the league during his brief time as Eagles offensive coordinator from 1995 to 1997. Gruden was largely a disappointment as a head coach after his early-career success in Tampa Bay, but he did make a few important hires before his coaching career came to a shameful end; during an NFL investigation, emails in which Gruden made racist, sexist, and homophobic remarks were discovered, resulting in his resignation.

It may be hard to conceptualize Payton in the same space as Shanahan and McVay given that Payton is roughly two decades older than the other two. But when you consider their ties to Gruden—and their proximity to the original designs of the West Coast offense—it feels fitting to cluster them together. These guys aren’t just the icons of modern NFL offense; they also serve as the meeting point for where the OG iterations of the system bump up against new-school versions.

Whether you’re going back a decade and a half to study Shanahan’s offenses in Houston and Washington or Payton’s in New Orleans or watching the present-day systems of the 49ers, Rams, and Broncos, you can see the foundational pieces that make up this generation of offensive schemes—and the small tweaks that each play caller has made over the years.

Shanahan is still a devotee to the original outside zone scheme his father and Gibbs made famous with the late-’90s Broncos. Three decades later, the goal remains the same: beating defenses toward the widest edge the offense can create. And this offense successfully creates the creases that it needs through its use of condensed formations, motions that send players of every body type flying across your screen, and a wide array of winning blocks on the edge.

When an offense is as efficient with outside zone as Shanahan’s is, you need only a couple of counterpunches in the run game to keep defenses honest—and Shanahan is just as good at manufacturing cutback lanes as he is at stressing a defense’s outer edges. His offense does a beautiful job of fooling linebackers into flowing over the top to stop the outside zone they’re anticipating, then opening up space between the tackles for running backs to exploit. The clip below is an example of split zone, where the extra blocker who would have been helping to widen the play-side edge instead cuts across the formation to seal the backside. When you can pair these two concepts together, defenses struggle to know where the point of attack will be.

McVay worked in an outside-zone-heavy system in Washington—which ranked top five in rushing yards in 2012 and 2013. And when he first took over as head coach of the Rams, he replicated what he knew—you can still see the bones of that running scheme in the current iteration of his offense. His offensive line isn’t as fleet of foot as it was in 2017, and the backfield certainly isn’t as explosive as what we saw when Todd Gurley was in the fold, but McVay can still control the edge with receivers who show up as blockers and put stress on the integrity of a defense’s run fit.

Today, the calling card of McVay’s run game is getting downhill, most often behind pullers and double teams. Some believe that has cost McVay’s offense some explosiveness, but the Rams make up for it in efficiency. They were top 10 in rushing success rate in 2024 thanks to runs you’ll see in the clip below, using counter and duo run schemes to give their backs easy yards.

Payton uses zone running schemes in his offense, too, but he’s not a dyed-in-the-wool outside zone disciple the way the Shahahan guys are. His run game typically looks more like what you see from present-day McVay: zone runs interspersed with bully-ball gap schemes.

While the similarities between the Shanahan, McVay, and Payton run games are fairly subtle, those in the passing game are not—especially on play-action. These three will ruthlessly attack the middle of the field after run fakes, using both sharp in-breakers and deep crossing routes. And with how effective each of these offenses is at setting up efficient and explosive runs, the threat of the handoff alone is enough to displace linebackers and safeties and create easy throwing windows.

Even if Payton, Shanahan, and McVay came to the league at different times (1997, 2004, and 2008, respectively), they belong to the same generation of play callers. And they have become the tastemakers for the current group of offensive architects.

Within the “family” of the Shanahan/McVay coaching tree, Kevin O’Connell is the most interesting branch. O’Connell totally missed the scheme’s formative years in Washington, joining the staff after both guys had left for Atlanta and Los Angeles. He served as coordinator there for only one year before McVay hired him for the same role in L.A. in 2020. He became a head coach in Minnesota two years later, on the heels of the Rams’ Super Bowl win in the 2021 season. But in spite of his limited time spent as a play caller prior to his head coaching job, O’Connell seems very devoted to the central tenets of the scheme. Since he took over in Minnesota in 2022, only the Detroit Lions have had more designed runs from under center. In watching the Vikings, it’s hard not to see the schematic resemblance to the 2016-17 Falcons or the 2017-18 Rams, as O’Connell’s menu of zone runs looks almost exactly like concepts you’d find from those eras.

McDaniel and LaFleur have spent as much time under Shanahan and McVay as anyone in that coaching tree, but they haven’t built their offensive staffs by poaching assistants from the system they grew to master. Instead, both have filled positions with coaches who operate along the edges of the West Coast offense—if not outside of it altogether. McDaniel’s staff is a bit closer to the core of the system, with assistant head coaches Jon Embree and Eric Studesville having worked directly with Shanahan or Gary Kubiak, Shanahan’s former boss in Houston. The rest of his staff consists of younger coaches from different systems, and it’s led to a unique approach to the run game. McDaniel uses more elements of the spread offense, creating a scheme that almost looks like Shanahan’s offense combined with Chip Kelly’s at Oregon. There’s a shotgun-based approach and a large menu of run-pass options, which hardly exist in the 49ers or Rams offenses. LaFleur, meanwhile, has deviated even further in building his staff, leaning more on veterans and coaches who spent more time in college than the pros. Instead of relying on the classic presentation of the Shanahan/McVay run game, LaFleur has turned to some spread-to-run tactics like McDaniel, but he’s applied even more creativity to vary the angles and mask his tendencies.

The end result of those different strands of the West Coast offense coming into contact with outside systems might just be Ben Johnson. Johnson learned the Holmgren and Mike McCarthy side of the West Coast offense through Joe Philbin and Mike Sherman, parts of Peyton Manning’s spread passing offense by working with Adam Gase, and some of Payton’s offense by working with Dan Campbell the past few seasons. He’s taken his vast exposure to different offenses and distilled it in ways that maximize the talent at his disposal without putting too much on his quarterback’s plate. In the run game, Johnson’s menu has been complete with gap and zone running schemes, which featured Detroit’s offensive line as one of the best units in the league.

Johnson can borrow from the play-action and dropback passing concepts of the Payton-Shanahan-Gruden trio too, using the same presentation to manipulate defenses even though he never worked directly in that offense. The new Bears head coach doesn’t belong to one tree, and it’s his versatile schematic background that made him the league’s hottest coaching candidate this hiring cycle. He essentially had his pick of the available jobs, and he chose Chicago, where he’s promised to tear up the playbook he used in Detroit and start from scratch.

It’ll be a few months before we find out how his new offense will look with the Bears, but the way he’s filling out his staff follows a familiar pattern. He’s brought in Declan Doyle, a former Payton assistant, as his offensive coordinator, and hired Press Taylor, who belongs to the Reid tree via Doug Pederson, as the pass game coordinator. Johnson’s playbook in Chicago should blend Reid’s spread-based interpretation of the West Coast passing game and Payton’s style of run game. You can find those two components across the league, but we’ve never seen them mixed. If Johnson succeeds in Chicago, we could see another branch of this massive coaching tree grow into prominence over the next few seasons.

The success or failure of the recent play calling stars to land head jobs—Johnson with the Bears, former McVay assistant Liam Coen with the Jaguars—will ultimately determine which direction the league’s offensive evolution heads in next. Payton, Shanahan, and McVay took the work of their schematic influences, expanded on it, and helped their assistants get jobs around the league. But it’s not just the ubiquitous “West Coast” tree that’s shaping how offense is played in the NFL. Eagles coach Nick Sirianni and offensive coordinator Kellen Moore, Colts coach Shane Steichen, and Cardinals offensive coordinator Drew Petzing are keeping Norv Turner’s branch of the Don Coryell coaching tree alive. Joe Brady, a former Payton assistant with ties to Turner’s tree, and Kingsbury, who doesn’t belong to any tree, were up for head coaching jobs this offseason after impressive years coordinating the Bills and Commanders offenses, respectively.

If those coaches from outside of the McVay/Shanahan extended universe find success, the NFL might finally be released from the stranglehold that tree has had on head coach hirings for nearly a decade. But if Johnson turns the Bears into an offensive power and some of those other coaches turn their teams into winners, the league’s decades-long infatuation with play callers will only grow stronger.