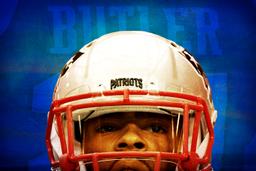

Malcolm Butler knows exactly how a movie about his life would unfold. A kid from Mississippi with nothing but a dream plays one year of high school football, fights off demons, works at a fast food restaurant, toils at a small college in the South, then somehow emerges from obscurity to make the NFL as an undrafted free agent. The raw rookie struggles to learn his new team’s complicated playbook but flashes signs of greatness. But it’s all building toward an unimaginably cathartic climax: the underdog walking off the field in a daze, mobbed by teammates, crying tears of joy.

That is The Malcolm Butler Story. Or at least the one America knows by now, beat by beat. The instant Butler intercepted Russell Wilson at the goal line to snatch victory away from the Seattle Seahawks in Super Bowl XLIX 10 years ago, the New England Patriots cornerback became a folk hero. “Malcolm,” says Josh Boyer, Butler’s position coach at the time, “was the right guy, at the right time, in the right spot.”

What Butler did was so inspirational, so impossible, so shocking that it’s easy to reduce him to a cinematic cliché. The truth is his life as a pro athlete did really unspool like a biopic—but in reverse. The most dramatic moment happened at the beginning. Nothing he or anyone else has done can ever compare.

“There are guys who played 15, 16, years,” Butler tells me, “and don’t get the love I get off of one play.” But when you’re known for making a play that changed the fates of two franchises, that immortalized and scarred dozens of players, that lifted up one fan base and traumatized another, that led to unfathomable personal glory, moving on is hard. Especially when you’re asked, after a career that didn’t end with that moment, to revisit it repeatedly. But now, almost 35 years old and retired, Butler has embraced what made him famous, even if he sees it as most don’t: a launching point, not a crowning achievement.

“That is always going to be there no matter what,” Butler says. “But you’ve got to keep going.”

By now, Butler knows the play as well as his social security number. Sitting in a booth in a suburban Houston restaurant on a December afternoon, he starts rearranging silverware to make an impromptu diagram.

At the time, the Patriots clung to a 28-24 lead late in the fourth quarter. It was second-and-goal, Seattle had the ball just outside New England’s 1-yard line, and the clock had ticked down under 30 seconds. Butler lined up on the outside, a few yards deep in the end zone, well off of receiver Ricardo Lockette. Inside and in front of Butler was veteran cornerback Brandon Browner, who stood opposite Jermaine Kearse. Butler, who had covered Kearse during the second half, recalls tapping Browner on the butt and asking him to confirm his assignment. “I said, ‘Who I got?’” Butler says. “He said, ‘You got the back guy.’” That meant Lockette. Browner’s job was to jam Kearse so he couldn’t pick off Butler. Butler pushes the salt shaker into the pepper shaker, showing me what Browner needed to do.

When Wilson took the shotgun snap, Browner jammed Kearse. Simultaneously, Lockette broke inside and looked for the ball. With a path cleared by Browner, Butler sprinted diagonally to get in between the receiver and the throw. “Malcolm has to take the perfect angle to get over the top and break this ball up for a no-yard gain,” says former Patriots cornerback Logan Ryan. “Intercepting it is almost impossible.”

Almost. Even from the coaches’ box of what was then the University of Phoenix Stadium in Glendale, Arizona, it was easy to see that Butler was moving extraordinarily fast. “He’s going to break this up,” Boyer remembers saying to himself.

Boyer had long known about Butler’s ability to cover a lot of ground quickly. He’d seen tape of the corner playing at Division II school West Alabama. “I have my notes on Malcolm,” Boyer says. “One of the things that I wrote was ‘good burst.’”

The coach remembers talking to Butler’s agent, Derek Simpson, from a tunnel underneath the lighthouse at Gillette Stadium in early 2014. Despite the conversation, Boyer had a sneaking suspicion that there weren’t many, if any, other teams interested. “Basically, Malcolm had nothing,” Boyer says. “Derek was trying to make it seem like he did.”

Coming into the 2014 season, the Patriots’ cornerback room was crowded. Darrelle Revis, Kyle Arrington, Alfonzo Dennard, Ryan, and Browner were all experienced vets. But Boyer thought that Butler was worth pursuing. “Malcolm was at the top of my list,” Boyer says. After all, he adds, “developing young players was a big thing for us because the expectation was that we were going to be good, and the expectation was that when they got to free agency, guys would probably have better opportunities elsewhere.”

After the NFL draft came and went without any team selecting Butler, Boyer tried to sell Nick Caserio, then the Patriots director of player personnel, on signing him. The pitch didn’t work: “I already had a position that had a lot of guys,” he says. Still, Boyer didn’t want to give up. So he took a risk and visited head coach Bill Belichick’s office. “Hey, Bill, I got this guy,” Boyer remembers saying. “We could sign him for $100. He’ll come.” The plea worked. “All right, all right, got it,” Belichick told him. “We’ll bring him in for a rookie tryout.”

At the time, Butler would’ve taken any NFL opportunity he could get. A few years prior, even a tryout would’ve been unlikely. After graduating from Vicksburg High in 2009, he played half a season at Hinds Community College before getting kicked out of school after he reportedly got into an altercation with a campus police officer. Not long after that, he started working at his hometown Popeyes—a detail that, predictably, appeared in almost every single article about his surprising rise.

Hinds eventually reaccepted him, and he played one more year there. Then he transferred to West Alabama, where he became an honorable mention All-American in 2013. But that wasn’t enough to make up for the gaps in his résumé. “I had some scouts come talk to me,” Butler says. “They asked me about my past troubles. That was that. I watched the draft, but I knew I wasn’t getting drafted. … I was, what, 24 years old? That’s old as a rookie. I’d lost some years just going through what I went through to make it to where I was.”

“Malcolm was the right guy, at the right time, in the right spot.”Josh Boyer

Before his trip to Foxborough, Butler had been on a plane only once—when West Alabama traveled to Texas to play Abilene Christian. During his first trip north, he lost his wallet. “Left it at the airport,” he says. Still, there was nothing that could break his almost irrational confidence. Well before making the team, Butler carried himself like Deion Sanders. “It’s nothing new,” he says. “You can ask people in my city how good of an athlete I was.”

During the tryout, though, humility crept in. Just a little. “A guy ran a comeback route during the trial, and I picked it off,” he says. “And I’m still thinking I’m in college, and I threw the ball [away], and the guy said, ‘You’re not down.’” All Butler recalls thinking was: Oh, shit.

The way Boyer remembers it, Butler’s performance was just “OK.” But in May, the Patriots signed three undrafted rookies—and one of them was Butler. He came to his first OTAs that month as a complete unknown. Yet the 5-foot-11 cornerback immediately stood out. “Malcolm was making plays all the time,” the coach says.

At one point, Belichick actually started to notice. “We’d be in the staff meeting in front of everybody, and he’d make a play,” Boyer says, “and Bill would be like, ‘Is this your guy? Is this your guy?’ Kind of being a smart-ass.” A week or so later, Belichick was still asking Boyer the same question. “Bill goes, ‘I don’t see him,’” Boyer says. “I go, ‘Bill, he’s the only one out there in red shoes.’” Butler was still wearing his team-issued cleats from college.

Ruby slippers and all, Butler made it to Patriots training camp. But this wasn’t West Alabama anymore. “He was so unprepared for the league,” Ryan says. “He didn’t know what Cover 2 was. He didn’t know nothing, man. He was playing straight off his instincts, street smarts. He had to learn a lot.”

Because Browner was facing a season-opening four-game suspension for violating the NFL’s substance abuse policy, Butler got more practice reps in camp than he would’ve otherwise. “He was out there with us a lot,” says former free safety Devin McCourty, one of New England’s defensive captains that year. “And I can’t imagine what he was out there thinking. You’re taking the field with Revis and all these veteran guys, and you’re just this rookie that was a walk-on.”

“He had just such a country background, and the odds of him even making it to the Patriots were so—he was working at Popeyes, you know what I’m saying?” says Ryan, a third-round draft pick in 2013. “So we were polar opposites, but we kind of hit it off. I had to teach him a lot, but I learned a lot of fight from him.”

That first summer with the Patriots, Butler earned two nicknames: “Scrap” and “Strap.” “Man, he was feisty. Super scrappy,” McCourty says. “His nickname ended up being ‘Strap’ because he was locking everybody down, strapping everybody up in practice. He just had this edge and attitude about him every single day.”

“He made plays early where you were like, ‘This guy could become a ballplayer!’” says former receiver Julian Edelman, a seventh-round pick. “And you were speculating, Why the hell did he not get drafted?”

Even when he was playing the wrong coverage, Butler often made the right play. “We’d be in Cover 2; he’d be in man-to-man,” McCourty says. “The [receiver] would run an end cut. Because he was in man, he would undercut it and get an interception. We’d be like, ‘No!’”

That happened at least three or four times, Boyer says. He and then–defensive coordinator Matt Patricia joked with each other about it. “We were like, ‘Maybe we should put that coverage in.’”

Sure enough, Butler made New England’s opening-day roster. “Never was on the practice squad,” he points out. Few people outside of Mississippi knew this, but he’d fulfilled a public promise he’d made that July. “You can go back and look at the Vicksburg newspaper,” he says. “When I didn’t make the team yet, I said, ‘I’m coming home to visit, not to stay.’”

Even as a rookie, Butler claims that he never had any self-doubt. Well, except for when temperatures in Massachusetts dipped below freezing. “I never felt cold like that,” he says. “I should’ve brung some more drawers.” When the Southerner complained about it once, receiver Brandon LaFell half-jokingly told him to “get [his] shit together” or he might get cut. Butler came back the next day with hand warmers, which he stuffed into his cleats.

Butler’s first year in the NFL was exceedingly undramatic. As the Patriots overcame a slow start and rolled to the best record in the AFC, the undrafted cornerback tried to make the most out of his limited playing time. Late in an October blowout of the Bears, he broke up two passes. He also started at safety in a lopsided December win over Miami. Butler was on the field for only 16.9 percent of New England’s defensive snaps during the regular season. But when he was out there, he wasn’t a liability. “I don’t know if he knew it, but I think for the rest of the guys, we trusted him,” McCourty says. “If he got in a game, it wasn’t like, ‘Why the hell is Malcolm in?’”

That January, Butler logged just 15 defensive snaps in the Patriots’ 45-7 victory over the vengeful Colts in the AFC championship game. He didn’t know if he’d play much, or at all, in the Super Bowl against the defending champion Seahawks, but he tried to stay focused. “Josh Boyer, he was like, ‘Malcolm, just keep working hard,’” Butler says. “‘You never know when your opportunity is going to come. You’re going to put West Alabama on the map.’”

“I said, ‘If this play shows up, I know what’s going on.’”Malcolm Butler

Leading up to Super Bowl XLIX, the Patriots defense, like usual, practiced plays that the other team might run. One, singled out by brainy football research director Ernie Adams, was a pass Seattle liked to call when it was deep in its opponent’s territory. There were several versions of it, including one where Seattle lined up in shotgun with one running back, one tight end, and three receivers. Two of them were positioned parallel to each other. At the snap, the inside receiver was supposed to get in the way of the defender covering the in-breaking outside receiver, leaving him open.

The Seahawks had scored on the play in the regular season, and when the New England offense ran it repeatedly before the game, the defense couldn’t seem to figure it out. “We didn’t have much success in practice defending the route,” Boyer says. “It was a pain in the ass at the time.”

Butler in particular kept getting scored on by the outside man, backup receiver Josh Boyce. He had played in one game all season. “If you see the whole clip, I end up dancing in the background,” Boyce says. “It’s pretty funny.”

Diagnosing the problem was simple. “The inside receiver got off the line and up into the end zone,” Belichick said in Do Your Job, a 2014 NFL Films documentary. “Malcolm didn’t really have enough awareness for the play, so he had to go all the way around the receiver and the defensive back, and there was just too much space, and it was an easy touchdown.”

In the film room the next day, McCourty says that Bill “tore into” Butler. That raised Ryan’s eyebrows. “Malcolm’s not going to be in during the game for that anyway,” he says. “So why are we really even correcting him?”

For his part, Butler didn’t really mind being called out. “Preparation rules the nation, and being prepared will put you ahead,” he says. “I said, ‘If this play shows up, I know what’s going on.’”

Before the game, Butler asked Edelman to borrow a pair of his red gloves. The receiver called him a rookie and said no. But as always, the undrafted free agent strutted onto the field with confidence. “I know I’m not starting, but I’m walking out the tunnel like this, with my head shaking,” he says, bobbing his head up and down.

With the game tied 14-14 at halftime, there was an opening for Butler. Patriots cornerback Kyle Arrington was struggling to cover Chris Matthews, a free agent receiver who hadn’t caught a single pass during the regular season. It was his 11-yard touchdown grab at the end of the second quarter that evened the score. “I can remember we talked about it at halftime,” Boyer says. “I said, ‘Look, if they hit us on one more, then we’ll make a change.’” Early in the third quarter, Wilson connected with Matthews for a 45-yard gain. Boyer had to make an excruciating decision. “Kyle Arrington is one of the toughest players I’ve ever coached,” he says. “And he did a great job on T.Y. Hilton the week before. To tell you how tough Kyle was—most people wouldn’t know this—Kyle had a shoulder [injury] and played in a couple of games, and he really couldn’t lift his arm. That’s how tough Kyle Arrington was.”

From the booth, Boyer called down to the sideline. “I said, ‘We’re going to put Malcolm in for Kyle,’” he recalls. The move wasn’t as strange as it seemed. “Someone asked me, ‘How the hell do you put an undrafted rookie free agent in the game?’” Boyer says. “And I said, ‘You’ve got to understand, we had two weeks of practice.’”

New England was also playing a lot of man-to-man coverage, Butler’s specialty. Right away, Boyer thought about putting Butler on Kearse. “Kearse was very good at running the entire route tree: short, intermediate, and deep,” he says. “And Malcolm could cover all those.” Kearse was a few inches taller than Butler, but, Boyer adds, “Malcolm had the ability to play bigger than what he was.” Still, Boyer didn’t want to mess with the matchups and throw the corners off: “That can be a mental thing for the guys.”

Browner, who’s 6-foot-4, then piped up and volunteered to switch to Matthews, who’s 6-foot-5. “I was like, ‘Perfect, that’s great,’” Boyer says. With Revis on Wilson’s top target, Doug Baldwin, and Browner locking down Matthews, the rookie was responsible for stopping Kearse. And for the most part, he did. In the third quarter, Butler broke up Wilson’s deep shot intended for Kearse. Then, late in the fourth, after Tom Brady’s touchdown pass to Edelman had just given New England the lead, Butler made a second highlight-reel play. On the Seahawks’ final drive, when they had first-and-10 just inside Patriots territory, Wilson again threw at Butler, who knocked the ball away.

Three plays later, Butler looked like he was on the way to making another spectacular breakup. On first-and-10 at the 38, Wilson dropped back and lofted a throw toward Kearse. Butler stayed with the receiver step for step, leaped, and tipped the ball. “A fucking unbelievable play,” Edelman says.

Both Butler and Kearse fell on their backs. “I thought it was over,” Butler says. “I thought it was over.” Somehow, though, the pass bounced off Kearse’s legs and into his hands. “I looked up,” Butler says, “and he caught the ball.” The rookie still had the awareness to push Kearse, who’d gotten up and started to run, out of bounds at the 5-yard line. “Ain’t no reason to sit there and look stupid,” Butler says. “You go try to punch the ball out, try to do something.”

For the Patriots and their fans, the catch brought back memories of New England’s Super Bowl losses to the Giants. Would Kearse become the new David Tyree or Mario Manningham? “It almost felt like,” Ryan says, “Here we go again.”

But the game wasn’t over yet. New England didn’t plan to concede a touchdown and just hope that Brady would save the day again. On first-and-goal, Wilson handed the ball off to Marshawn Lynch. The Pro Bowl running back looked bound for the end zone until Patriots linebacker Dont’a Hightower seemingly came out of nowhere to tackle him at the 1. That ended up being the second-most important play of the game.

With Seattle so close to scoring and the clock ticking, Belichick’s obvious move would’ve been to call timeout. He didn’t. Over the years, he’s said that it seemed like the Seattle sideline was in disarray. He didn’t want to give his opponent time to regroup. The Seahawks were in 11 personnel for the next play: one running back, one tight end, and three receivers. Belichick told Patricia to “go goal line.” Boyer quickly radioed down to safeties coach Brian Flores about putting in Butler, who he knew could handle another man-to-man assignment. “I said, ‘Flo, send Malcolm,’” Boyer recalls.

From the sideline, Flores shouted, “Malcolm, go!”

“I turned around,” Butler says, “and I said, ‘I got you.’”

At that point, Seahawks coach Pete Carroll had to call a running play. Lynch already had 102 rushing yards and a touchdown. Surely he’d be the one to punch in the game-winner. Yet, as Boyer says, the Patriots were in their beefed-up goal-line defense. “I don’t think they get a yard,” Ryan adds.

Sure enough, Seattle lined up in what appeared to be a passing formation. It was a familiar look—the one that, thanks to Ernie Adams, the Patriots had seen before. Butler still thought Lynch might get the ball—“It’s on the goal line!” he says—but he was ready for a pass. “If you throw this ball, it’s on. Sometimes you’ve just got to believe in yourself and say, ‘I’m going to do what I’ve got to do.’”

Browner, it seemed, knew what was coming and let Butler know. Looking back, Boyer knows that they’re lucky Lockette didn’t break outside. “There wouldn’t have been anybody within 10 yards,” he says. “Hell, I probably would’ve gotten fired. You’ve got an undrafted rookie in the game, and you’ve got the game-winning touchdown.”

Of course, Browner jammed Kearse, and Lockette broke inside. And Butler managed to do what he couldn’t in practice: make a beeline toward the path of the ball. “That’s exactly what Malcolm did,” Ryan says. “I don’t think he looked at the receiver. He went straight with his gut.”

Wilson’s pass was high. Butler closed fast and beat his man to the ball, which he caught and pinned tightly to his chest. “The key to that play is that he went for the interception. That’s the most ridiculous thing about it,” McCourty says. “Most guys would’ve been like, ‘Man, this is close. I’ve got to just break this pass up and live to see another down.’”

“That ball stuck to his pads like Velcro,” Ryan says.

After securing the interception on the goal line, Butler collided with Lockette, landed in the end zone, tucked the ball, and fell forward to the 1-yard line. “Sometimes you’ve got to know what’s at stake,” Butler says. “And you’ve got to want it the most.”

The play happened so fast that everyone in the stadium, except for maybe NBC’s Al Michaels, needed at least a few seconds to fully grasp what they’d just seen. “Pass is intercepted at the goal line, by Malcolm Butler!” the legendary announcer shouted. “Unreal!”

From his spot on the sideline, Ryan struggled to process it all. “What does that mean? Is it a touchback? Is it our ball? Was it a safety? Where’s he at?” Ryan says. “I just thought of all those things. Like, Yo, there’s no way that’s real.”

In the coaches’ box, Boyer felt frozen. “The place erupted, and basically I’m just sitting in my seat like I was at school or something, you know?” he says. “I didn’t get up. I didn’t yell. It was just one of those things.” It was, he admitted, a relief. “I’m like, ‘He’s got it. This is awesome.’”

After Butler hit the ground, he buried his head in the turf. “I’m sure he didn’t know what the heck was going on at the time,” Ryan says. “But it was surreal.” One of the first Patriots defenders to reach Butler afterward was Hightower. “He was on top of me, crying,” Butler says. “I said, ‘I ain’t heard a grown man cry in a long time.’”

As his teammates helped him off the field, Butler himself sobbed. “It was a crazy, crazy thing,” Ryan says. “Me and Malcolm are super close. That’s like my brother. I said, ‘Bro, why are you crying so hard though?’ Just made fun of him immediately.”

“The key to that play is that he went for the interception. That’s the most ridiculous thing about it.”Devin McCourty

“I don’t know if it was sweat or tears,” Butler deadpans.

Even for the NFL, the moment was uniquely dramatic. With the Super Bowl on the line, there had never been such a stunning—or, if you’re a Seahawks fan, sickening—reversal of fortunes. Butler’s pick clinched Brady and Belichick’s first title in 10 years. It also may have killed a potential Seattle dynasty.

“There’s two shots that really capture the moment,” says Fred Gaudelli, then the executive producer of NBC’s broadcast. “Richard Sherman’s visceral reaction, almost as if he’s about to vomit. That’s what it looked like. Then Tom Brady jumping up and down like an 8-year-old.”

After yelling, “Oh my God!” and hugging offensive coordinator Josh McDaniels, Brady composed himself enough to officially seal the victory. With 20 seconds remaining and New England on its own 1, he drew Seattle offside and then kneeled down to end the game.

A brawl briefly broke out sometime in between all of that. In the aftermath of the loss, the Seahawks were understandably distraught. One player allegedly punched a locker so hard that he broke his hand. As he sipped a bottle of Hennessy, Lynch reportedly lamented, “These motherfuckers robbed me!” Offensive coordinator Darrell Bevell owned up to calling the fateful final play, then dug at Lockette without naming him, saying, “We could have done a better job staying strong on the ball.” Carroll blamed himself. “That’s my fault, totally,” he said, and he inexplicably claimed that his team was “playing for third and fourth down” to make sure New England had no time to come back. Wilson also took responsibility. “We were right there,” he said. “So I put the blame on me.”

Boyer understood why the Seahawks were so stunned. “I’ve lost three Super Bowls. … That feeling is about the same as losing a close friend,” he says. “There’s so much sacrifice, with time away from your family. It’s a very emotional game. There’s such a finality to it.”

That night in February 2015, Butler had no clue that his interception would be responsible for a decade of finger-pointing and conspiracy theories among Seahawks players and fans. He was too busy celebrating. There’s footage of Brady, the game’s MVP, hugging Butler and yelling, “Malcolm, are you kidding me?!”

“I used to pick him off at practice all the time,” Butler says with a smile. “So that was nothing new.”

The next morning, Butler and Edelman headed to Southern California to make an appearance at Disneyland. At the airport, the vet turned to the rookie and said, “See, if you would’ve worn those red gloves, you wouldn’t have caught the ball,” Butler recalls. (“I don’t remember that, but I probably did say that,” Edelman says.) After riding on a float in the Main Street parade, they flew back east. To Butler, the whole thing felt miraculous. When he left New England on the team plane a week earlier, he never expected to return on a private jet.

For a little while at least, the party continued. Butler rode on a duck boat during the Patriots’ championship parade through Boston, presented a Grammy Award to Beck, and received a big gift from Brady: his Super Bowl MVP prize, a red Chevrolet Colorado truck. Then his hometown of Vicksburg honored him—as promised, he came to visit, not to stay.

Eventually, Butler got back to work. “Him and I had a conversation probably within a week after the Super Bowl,” Boyer says. “And his big thing was, ‘Hey, I don’t want to let this one play define me.’”

That spring, Brady playfully gave Butler a hard time about his newfound fame. “Brady teased him,” McCourty says. “Malcolm, have you ever heard of David Tyree? You know who that is?” Brady wasn’t the only one who got on Butler. “Whether it was Tom, whether it was Bill, somebody would always say to him, ‘Well, what are you going to do now?’” McCourty says. “We didn’t want to make him feel bad, but I think everyone saw the potential he had, and I don’t think anybody wanted him to take that one play as, like, ‘That’s my career.’”

In 2015, Butler didn’t just become a starter. He became a Pro Bowler. “I still remember the Giants game, him going toe-to-toe with Odell Beckham and how big of a deal that was,” McCourty says. “He took the next step, which was really cool to see.”

The next season, Butler was named an Associated Press second-team All-Pro while helping New England win its second Super Bowl in three years. Clearly, he was more than a one-pick wonder. “If I was trash, the NFL would’ve gotten rid of me after that, especially playing for Bill Belichick,” he says. “I knew I was a good player, a good teammate. It just didn’t work out all the way how it was supposed to.”

In 2017, there were contract negotiations between the Patriots and Butler, a restricted free agent who hoped to sign a long-term deal fit for a Pro Bowler. But the team stalled. Then it gave $31 million guaranteed to cornerback Stephon Gilmore. Butler did sign a first-round tender with New England for $3.91 million that spring, but as far as he was concerned, he was still underpaid.

If Butler was angry about the situation, the bad blood didn’t seem to spill onto the field. Starting opposite Gilmore that season, he finished with two interceptions, three forced fumbles, and 12 defended passes. And for the second straight year, the Patriots reached the Super Bowl. Then came the second-most shocking, cinematic twist of his career: Before the title game against the Eagles in Minnesota, Belichick benched him.

While every member of the media was trying to track down why the Patriots had relegated one of their better defensive players—a guy who already had a Super Bowl–winning play on his résumé—to the sideline, Eagles quarterback Nick Foles was on his way to throwing for 373 yards and three touchdowns. Some of Butler’s teammates were incredulous. At halftime, McCourty says he remembers imploring Flores to put him in the game. “He was like, ‘The head coach said we can’t.’”

In his press conference after the 41-33 loss, Belichick predictably stonewalled all questions about the decision. When asked if Butler didn’t play because of a disciplinary issue, he said, “No.” Afterward, Butler sounded like he’d been blindsided. “They gave up on me,” he told ESPN’s Mike Reiss.

“It is what it is. It was a coach’s decision.”Butler

Over the past seven years, players, reporters, pundits, and fans have never stopped speculating about Butler’s benching. “I just felt bad for him,” McCourty says, “because I’m like … nothing’s ever going to come out about this, and he’s going to have to deal with it.”

Hell, even the Patriots owner has weighed in. In the 2024 Apple TV+ docuseries The Dynasty, Robert Kraft said only this: “What has been told to me is that there was something personal going on between Bill and Malcolm that was not football related.”

Maybe the best clue to what really happened can be found in It’s Better to Be Feared, ESPN senior writer Seth Wickersham’s definitive book about the Brady-Belichick era. In the author’s words, Butler and Patricia “exchanged heated words” at a Super Bowl–week practice over the cornerback’s perceived “lack of effort.” According to Wickersham’s reporting, Butler blamed the coaches for sitting him.

At lunch, Butler anticipates the question like Ricardo Lockette’s slant route. By the time we met, he’d practiced his answer over and over. “It is what it is,” he says, echoing Belichick. “It was a coach’s decision.” He doesn’t elaborate beyond that, other than to stress that he’s still fond of his former coach. “He gave me an opportunity,” Butler says. “You’re here because he gave me an opportunity and I gave myself an opportunity. I respect New England. I respect him. I respect everything he’s done.”

There’s no anger in Butler’s voice. He just has no interest in giving into curiosity. It’s hard to know why he’s keeping the mystery alive, but it feels like simple self-protection. Over the past 10 years, he’s had to share his greatest moment with the world. He prefers to keep his lowest one for himself.

In 2018, Butler finally signed an eight-figure contract—with the Tennessee Titans. In Nashville, he reunited with Ryan. It was bittersweet for the two former Patriots. As Ryan points out, division games at noon in Jacksonville just don’t feel the same as snowy battles in Foxborough.

Occasionally, opponents talked trash to Butler about his recent past. But he was ready for it. “You got benched in the Super Bowl,” one unnamed receiver said. “Shut up.” Butler’s response? “I told him, ‘It’s Week 13, man. You got 283 yards.’”

Tennessee did become a playoff team under coach Mike Vrabel in 2019, but Butler broke his wrist that November and missed the Titans’ run to the AFC title game. He played one more year there before getting released. Then he hooked on with Arizona, but before the 2021 season, he decided to retire. “If you’re not prepared mentally,” he later said of the decision, “you can’t do nothing physically.”

In early 2022, however, Butler heard from an old friend: Belichick. He wanted to sign Butler. McCourty, who was about to ink his last contract with the Patriots, couldn’t believe it. “[Butler] calls me, and he is like, ‘Hey, what are you about to do in free agency? Bill just called me,’” McCourty recalls. “I’m kind of skeptical. I think I was in Florida at the time with my kids, and I was like, ‘You would come back to the team?’” Butler reassured him that there’d be no problems. “If it was that bad,” Butler says, “I would never return to New England.”

Butler did return on a two-year deal, but his second stay didn’t last long. That August, the Patriots released him with an injury settlement. He never played another NFL down.

Butler’s exit from pro football was much quieter than his entrance. Last March, he announced his retirement in an interview with a local TV station in Texas. He coaches football now at St. Thomas High School in Houston.

The most cinematic part of his life may be over, but his story isn’t. The intensity of the NFL can make it feel like a lifetime, which can make the realization that it’s not even harder to grasp. “At the end of the day, you’ve just got to keep going,” Butler says. “It’s not going to be perfect, but you’ve got to keep going.”

He still visits New England to see his son, Malcolm Jr. When he returns, he’s treated like a conquering hero. Last September, he and dozens of former teammates attended a Super Bowl XLIX reunion in Foxborough. That afternoon, he rang the ceremonial bell on the Gillette Stadium lighthouse. And then the Patriots played the Seahawks.

Sometimes, Butler admits that he’ll think about his famous interception, pinch himself, and say, “Whew!”

“You knew his life was going to change,” Edelman says. “That was one of the absolute craziest plays, by a kid that was working at Popeyes 18 months before.”

These days, Butler wants to write an autobiography. He hopes the movie will come later. When I asked who he’d pick to play him, he thought about it for a second and said that there’s only one person up to the task: “Probably me. Because I want to tell the truth, and I want to be me. And I want to sound how I sound and be the person I am.”

After Brady gifted him his red MVP Chevy, Butler went back to the dealership and traded it in for one in black. “It was all in the media,” he says. “I didn’t want to be flashy.” Today, the 10-year-old pickup has only about 33,000 miles on it. It mostly just sits there, outside his house. “That’s a trophy,” Butler says. “Not a truck.”