Are We Sure NBA Expansion Is a Good Idea?

It’s been 21 years, the longest drought in history, since the NBA last expanded. Is there enough talent now to support two new teams? Or would it dilute the league? We surveyed a dozen NBA figures.It’s NBA Expansion Week at The Ringer! With a break in the schedule, we’re examining one of the biggest questions about the future of the league: Should the NBA expand beyond 30 teams? We’ll examine all the possibilities and complications, plus take some strolls down memory lane and examine some expansion teams of the past. We’ll bring it home at the end of the week with a hypothetical mock draft and a deep dive on potential future team owners.

Close your eyes for a moment and imagine you’re sitting courtside at Seattle’s Climate Pledge Arena. It’s opening night of a new NBA season, and the SuperSonics are about to take the court for the first time since 2008. The place is packed, from the luxury suites to the top of the upper deck. It’s positively electric. Euphoric.

Sonics legends Gary Payton and Shawn Kemp fire up the crowd with a pregame rally. Squatch rappels down from the rafters, where a spotlight illuminates the Sonics’ 1979 NBA championship banner. Eddie Vedder belts out the national anthem.

Every downtown sports bar is filled. The whole city—the whole league—is buzzing with anticipation.

The lights go down, a dramatic beat pulses, and the introductions begin …

“A 6-foot-5 guard from Arkansas … Isaiah Joe!”

“A 6-foot-9 forward from Dayton … Obi Toppin!”

“A 7-foot center from Bosnia and Herzegovina … Jusuf Nurkic!”

“A 6-foot-7 forward from Iowa State … Georges Niang!”

“And a 6-foot-4 guard … from Washington … Markelllle Fultz!”

The excitement is palpable. The quality of basketball, not so much.

Now imagine a second new team, debuting that same night in Las Vegas, helmed by Dennis Smith Jr., Collin Sexton, Cam Whitmore, Harrison Barnes, and Thomas Bryant.

Imagine how long it might take these new teams to become competent.

Imagine the slow drain of role players across 30 existing squads as they cede talent—through an expansion draft and free agency—to the new franchises.

Imagine a league with 36 more roster spots, to be filled by players from the G League, Europe, and beyond—players who, in 2025, were deemed undeserving of an NBA contract.

To paraphrase an old commercial slogan: “NBA expansion: It’s faaannn-tastic!”

What, too dour? Too simplistic? Too assumption-filled? Perhaps. At this moment, without an official timeline or process from the NBA, assumptions are all we have to envision what a 32-team league might look like. And it’s been 21 years since the Charlotte Bobcats came into being—the longest stretch in NBA history without adding a team—and much has changed in that time. But as the NBA inches ever closer to a two-team expansion—with commissioner Adam Silver now talking about it as a virtual fait accompli—these are the concerns that talent evaluators, franchise owners, and league officials must soon grapple with.

As part of The Ringer’s NBA Expansion Week, we’re attempting to tackle those questions. Is there truly enough talent to support two new teams? And to do so without degrading the product? Without hurting the quality of play? Without impairing existing teams’ ability to build a complete rotation? To borrow a pet rhetorical device from The Ringer’s Podfather: Are we sure expansion is a good idea?

We surveyed a dozen NBA figures, from scouts to team executives to owners, and found opinions across the spectrum, from cheerily optimistic to profoundly skeptical about what another round of expansion would do to (or for) the league.

“Of course it’s going to be worse,” said a veteran team executive in the Western Conference.

“It'll hurt the product initially, just like it did the [other] times,” said an Eastern Conference executive.

“Maybe there’s an initial impact of talent dilution,” said another Western Conference team exec, before adding, on a more hopeful note, “Within a few years, it stabilizes.”

As a business matter, the allure of expansion is obvious: League insiders believe franchise fees for two new teams could generate as much as $12 billion, to be split by the current 30 owners. New markets could bring in hundreds of thousands of new fans. More teams mean more jobs for players, coaches, scouts, and trainers. Everyone wins!

But as a basketball matter? Is expansion actually good for the game? That’s not nearly as clear. Nor has it even been closely examined. When NBA figures and pundits talk about expansion, it’s usually about the where and the when but seldom about whether it’s wise.

“The talent levels are higher than they have ever been,” former Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, who retains a share in the team, said in an email. “So I have no issues about dilution. … I’m all for expansion.”

Some of the folks who scout and sign players for a living are not so sure, or sanguine.

“I mean, the quality [of rosters] goes down. Let’s be realistic,” said the Eastern Conference exec. “We’re saying in today’s NBA that depth wins, and so you’re going to take depth away from the top-tier teams. And they’re not going to be as good. We already struggle with some of these starting units that some teams trot out there.”

It’s practically an article of faith in NBA circles that there is, as Cuban says, more talent than ever, due to the game’s global expansion. About one-fourth of NBA players today were born outside the United States. The NBA now operates a 31-team minor league, the G League, to incubate young pros.

The general increase in basketball talent is indisputable. It’s the quality of that talent that some observers (this author included) view with skepticism. Sure, you can find dozens of replacement-level NBA players now—a Lindy Waters III here, a Jae’Sean Tate there, an entire G League of bench guys—but mere competency doesn’t drive winning. Or ticket sales. Or ratings. A roster of 15 merely competent players will get you 25-30 wins a year and get the general manager fired.

The NBA has forever been a league driven by superstars, by the guys who make us leap off the couch, mouths agape. And by at least one measure, that pool has hardly grown in the past quarter century.

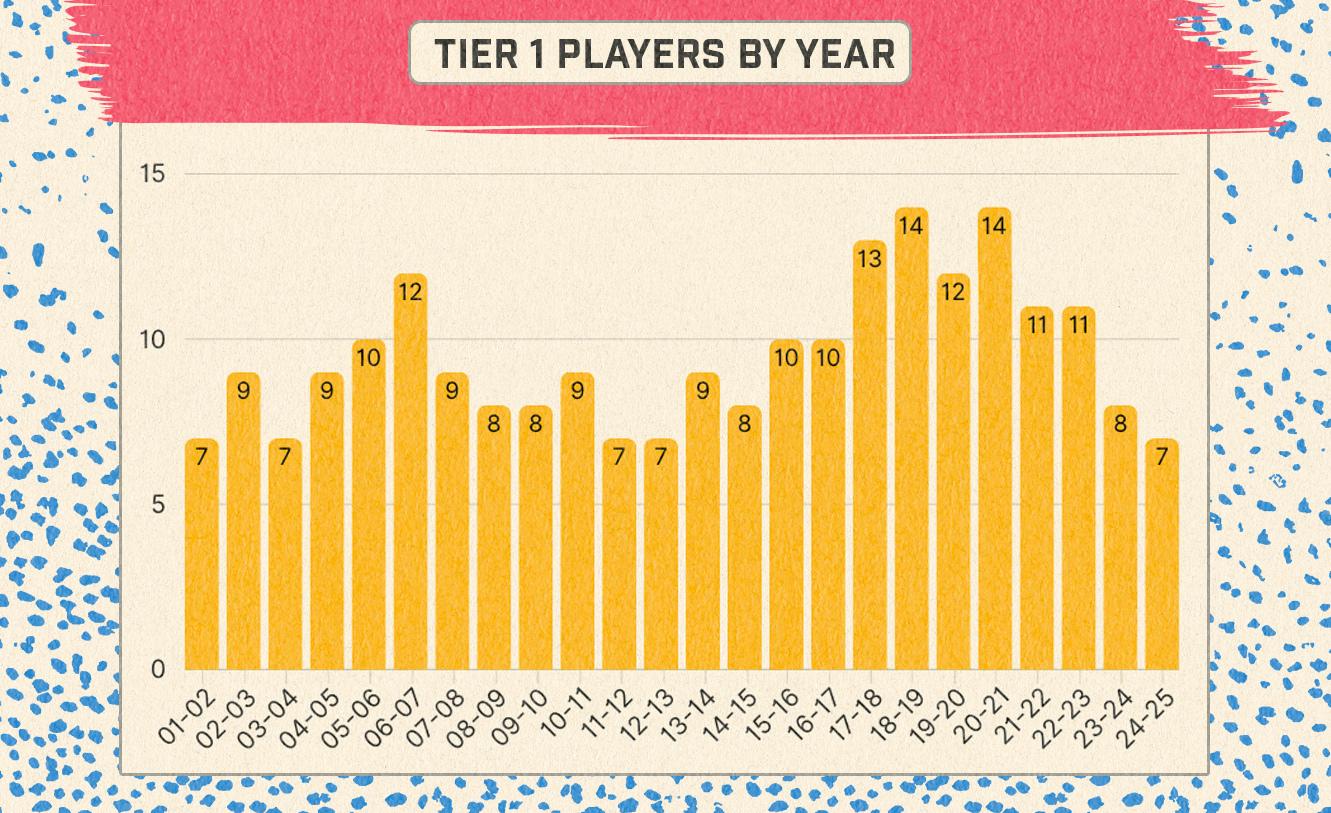

“If you look at just the last four years, it’s no different than the preceding 20 years,” says Taylor Snarr, the creator of estimated plus-minus.

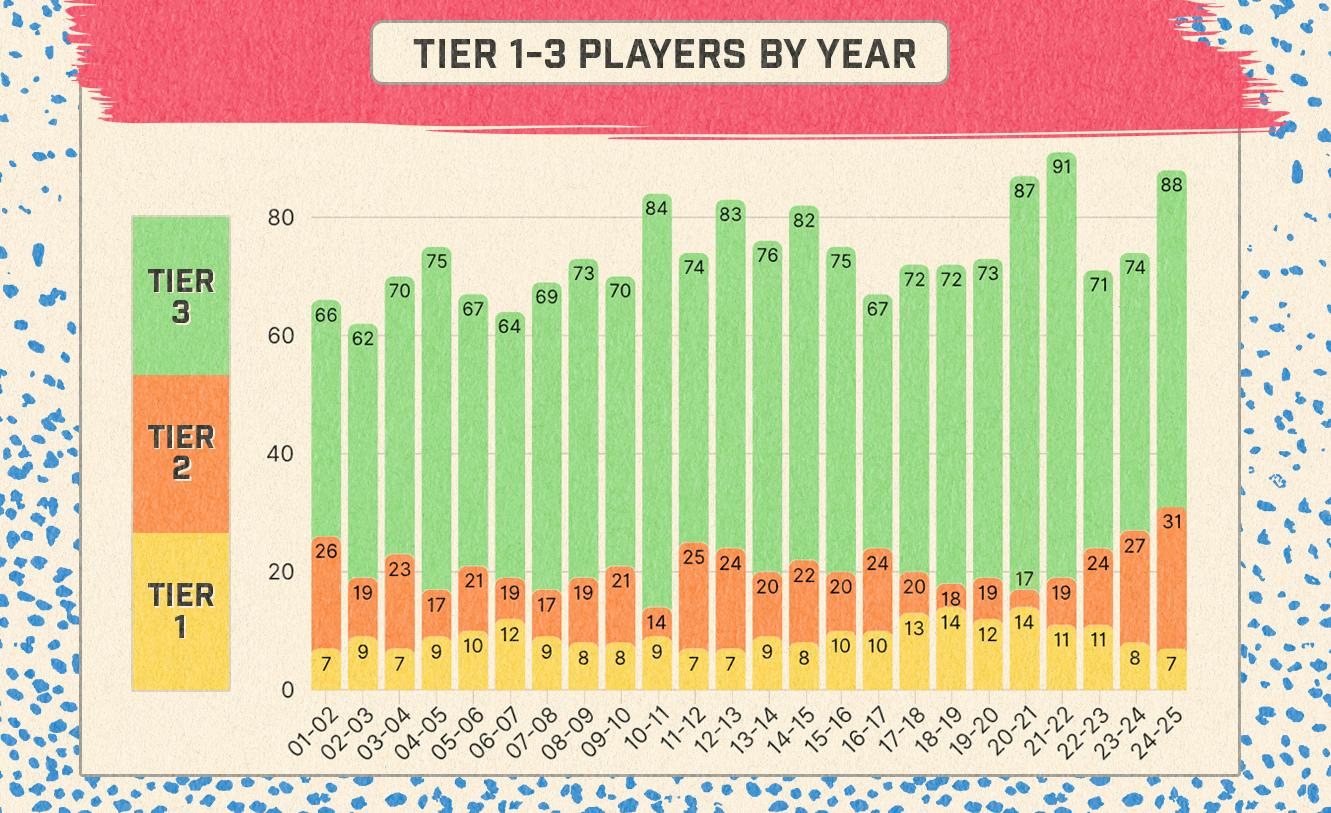

At The Ringer’s request, Snarr analyzed every season from 2001-02 to the present to assess how many true “superstars” there are in a given year. To do so, Snarr rated players based on EPM, widely considered the gold standard of publicly available, all-in-one impact metrics.

The verdict? The NBA has seen a modest uptick in star quantity across the past 24 years—from an average of about 8.5 superstars in the first five seasons to 10 superstars in the most recent five-year span. There are seven players who would qualify this season, the same number as in 2001-02.

“It is more or less fairly flat,” Snarr says. “I really don’t know if that would be enough to support an expansion.”

What exactly makes an NBA superstar? A franchise player? How do we separate the superstar from the average star? Is it just the gaudiness of their box score stats? Or is it the players who, in modern parlance, impact winning the most? How much of stardom is about production (stats) vs. entertainment value (the guys you’d pay to see)?

Because when you’re creating a team from scratch, you’re not just building a roster or trying to win games. You’re trying to build a following, to win hearts and minds. If your franchise star is Anthony Edwards, congratulations! People will pay to see him, win or lose. If your franchise star is Rudy Gobert? Well, he’ll make your team a winner, but you’ll need Edwards to score points and sell season tickets.

So, an obvious disclaimer: There’s a lot of “eye of the beholder” in these discussions, generally, even among the coaches, scouts, and executives who get paid to determine such things.

That’s why we turned to Snarr, a former analytics staffer for the Utah Jazz, whose EPM model and accompanying website, DunksandThrees.com, are universally respected in the analytics community. We needed an objective measure of a player’s impact. (Still: This remains an inexact science. Deciding where to draw the statistical cutoffs between various classes of “stars” is based in part on feel and, well, the dreaded eye test. Your results may vary.)

Using EPM, Snarr separated top players into three tiers: superstars (EPM of 2.4 and over in a given season), stars (EPM between 1.45 and 2.39), and significant contributors (EPM between 0.45 and 1.44). Those thresholds generally align with what you’d intuitively expect. The superstar tier last season included MVP Nikola Jokic (4.18), as well as Joel Embiid (3.70), Shai Gilgeous-Alexander (3.07), Luka Doncic (2.92), and Giannis Antetokounmpo (2.83). The second tier included everyone from, at the high end, Donovan Mitchell, Damian Lillard, and Devin Booker to, at the low end, Franz Wagner, Desmond Bane, and Trae Young. The third tier included Karl-Anthony Towns and Jaylen Brown down to Bradley Beal, Zach LaVine, and Malik Monk.

In short, you can build a contender around any of the Tier 1 guys. You can win a lot of games with the Tier 2 players, but you’ll probably need multiple of them to make a deep playoff run if you lack a Tier 1. And though some Tier 3 guys can play at a Tier 2 level in a given season, most of them are best suited as second or third bananas next to higher-tier stars.

To use an (admittedly tired) comic book analogy: The NBA is absolutely flush with Robins but still limited in its Batman supply. Pascal Siakam, Domantas Sabonis, and Bam Adebayo are fantastic talents and great supporting stars but ill-suited as leading men. Think of Mikal Bridges—a borderline All-Star and core-four player for a Phoenix Suns team that made the 2021 Finals but a miscast no. 1 in Brooklyn before a trade to the Knicks, where he’s again a fantastic fourth wheel.

If you look at Tiers 1 and 2 over the past decade, you find only a nominal increase in qualifying players—from a combined 30 players on average from 2001-06 to 34 from 2020-25. But dive into Tier 3, and a different picture emerges: It’s growing, substantially. Over the past five seasons, an average of 82 players per year qualified as Tier 3—up from 68 per year in the first five years of the analysis. There are 88 players in Tier 3 so far this season, compared to 66 in 2001-02.

So yes, it’s true: The league really is deeper than it’s ever been, with more talent and skill than we’ve ever seen. The data backs up the eye test. It’s just that the explosion of talent is mostly at the “significant contributor” level—the ace shooters, the lockdown defenders, the rim protectors, the indispensable starters who might make the occasional All-Star team but can’t carry a franchise.

Think of these tiers through the prism of the reigning champion Boston Celtics. They’re perennial contenders because of their superstar, Jayson Tatum (consistently Tier 1), and costar, Jaylen Brown (who varies between Tiers 2 and 3 in EPM), but they won the 2024 title on the strength of their top-shelf role players, like Derrick White, Jrue Holiday, and Kristaps Porzingis. Holiday has been an All-Star twice, Porzingis once, and White never. All three were in Tier 2 last season based on EPM. None of the three could carry a franchise on their own. (Even that trio combined on a roster lacking Tatum and Brown might struggle to win 41 games.)

Or consider the Zach LaVine and Brandon Ingram types—highly skilled, high-scoring players who have made an occasional All-Star team and earned max salaries but are best suited as complementary stars, not leading men. LaVine led the Chicago Bulls to a winning record just once in six seasons. Ingram led the New Orleans Pelicans to just two winning seasons in five years.

“How many of those players, the third-tier or middle-tier players, can you play through?” Snarr said.

All of which tracks with the general perception around the league.

“Most sports don’t have this huge disparity between the top players and the next tier down,” said another veteran Eastern Conference executive. “We have by far the largest gap of any sports between your top set of five to 15 to 20 players and the average player.”

If an expansion draft were held tomorrow, the Seattle and Vegas teams might poach a few Tier 3 players from existing rosters or sign them in free agency. But there’s virtually no chance of them swiping anyone from Tier 1, and very little chance of snaring anyone from Tier 2. So the new franchises would be bereft of high-impact players, but their creation would chip away at the depth of everyone, from the title contenders and the playoff hopefuls to the tankers and rebuilders.

Most teams today are in a perpetual scramble to find reliable, well-rounded rotation players—the sixth-through-10th guys who can be the difference between the playoffs and the lottery—and they’re not that easy to replace.

Or think of this all another way: In any given season, there are at least four to six teams that have no identifiable star—or even a second-tier star—to build around. It’s easy to dismiss the tanking teams, like Brooklyn and Washington, because they are bad by design. But consider the Utah Jazz, who have a legitimate star in Lauri Markkanen and are terrible anyway. Or the Portland Trail Blazers, who have accumulated some blue-chip talents (Scoot Henderson, Shaedon Sharpe, Donovan Clingan) but still can’t win half of their games. Or the Chicago Bulls, who got nowhere for years despite acquiring high-priced talents like Zach LaVine, DeMar DeRozan, and Nikola Vucevic.

Another factor to consider: The NBA is enjoying a bit of a talent bubble, with several late-career stars—LeBron James (40), Stephen Curry (37 next month), and Kevin Durant (36)—still playing at an All-Star level, defying all historical trends. Is this an anomaly or a new normal owing to sports science and modern training? When they’ve retired, will the total number of stars dip? Or will the generation behind them also push their primes into their late 30s?

The reality is, star acquisition in the NBA is a zero-sum game. There are a finite number of true superstars and a slightly larger (but also finite) group of Tier 2 stars in any given year—and those stars tend to gravitate toward one another. Every team with a solo star is trying to land a costar, or two. Which means that some teams have multiple stars, and some teams have zero. Add two more teams, and you’ll have two more franchises without a star—or hope. And even the best teams will likely lose some depth.

“I think that in the short term, yes,” said a talent evaluator for a Western Conference team, “but in the long term, it will actually help teams to focus on their player development and give a chance to the guys that are in a limbo, to give them the opportunity to sign a player that they weren’t so sure about. … It will water it down in the short term, but I think that in the long term, I think that it’s a healthy thing.”

So, about all those assumptions we referenced earlier …

There’s a lot we don’t know yet about how the NBA will expand, or even when. (“It’s not preordained that we will expand this time,” Silver said last June.) We don’t know what the rules of the expansion draft will look like or how many players can be protected by the existing teams. Will the new teams be barred from the no. 1 pick in the draft—as the Toronto Raptors and Vancouver Grizzlies were in 1995 (and through their first three seasons)? Or even be barred from a top-three pick, as the Charlotte Bobcats were in 2004 (before trading up to get the second pick)? Will the new teams initially be held to a lower salary cap, as the Bobcats were?

The truth is, we don’t even know when the league will expand, or to which cities. League insiders generally believe it will be Seattle and Vegas, but other cities will surely make bids whenever the process begins.

About that: The process hasn’t actually begun, either, and it’s not clear when it will. League sources say it could take three to five years from the time the expansion process begins to the day the new teams actually take the court. It might be 2030 before we see the resurrected Sonics or the Vegas Vipers or the Mexico City Marauders.

The main holdup right now, per league sources, is the protracted sale of the Celtics franchise, which was put on the market last July by majority owner Wyc Grousbeck. Sources say league officials are eying a sale price of at least $6 billion, in part to set a baseline for the expansion franchise fees (and, of course, in part due to the Celtics being one of the marquee franchises in pro sports). But that hasn’t come to pass yet, and the team remains for sale.

“Now that the Celtics [sale] looks like it’s just taking a lot longer, and it’s going to come in at a lower price, everything [with expansion] has gotten pushed back,” said a source who frequently speaks with team owners. Another plugged-in source added, “This is slowing down. It’s not happening anytime soon. I don’t think they have the votes for it.” The source said owners and league officials are now “thinking much more long term” about all the implications, both financially and competitively.

There are other theories about the delay circulating (which were dismissed by league officials but are worth noting here anyway): that the NBA is more focused on starting a new European league first. That the league is waiting for LeBron James and perhaps Stephen Curry to retire so they can join an investment group to buy a team. That the league wants to first assess how recent trends in parity (up) and TV ratings (down) play out over the next few years.

And there are indeed some concerns among existing owners about the potential risks of expanding. Have league officials studied potential talent dilution? That’s unclear. A league spokesman would not directly answer the question, saying only, “As we have said previously, it is premature to discuss expansion, and there is nothing new to share at this time.”

But Silver himself has occasionally invoked the d-word when asked about expansion. “I also have to look at the potential for dilution of the existing talent we have before we expand,” Silver said in June 2017. At that time, he said, team owners preferred “focusing on the health” of the existing franchises “and the quality of the competition.”

Silver repeated the sentiment last June, saying: “It’s on the league to look holistically, because there is the dilution, of course. Let’s say we expand by two teams: What does that mean for talent? I feel great about where the talent is right now in the league, but those players have to come from somewhere.”

And as recently as December, when asked about the potential “pitfalls” of adding teams, Silver said, “Our pitfalls are dilution of talent and dilution of economics. … We want to make sure that if we expand, those teams can be equally competitive.”

So the issue is certainly on the league’s radar. It’s also a concern to team executives, though few have spoken about it on the record. Sam Presti, the Oklahoma City Thunder general manager, noted in a press conference last fall that expansion rules were written in the early 1980s and would not “meet the smell test” in today’s NBA. “Team-building,” Presti said pointedly, “is so much different than it was at that point in time.”

Finally, consider the Charlotte Bobcats. Do you even remember the Bobcats? They arrived as an expansion team, the NBA’s 30th franchise, in 2004—a replacement for the original Charlotte Hornets, who had departed for New Orleans two years earlier.

Their opening-night starting five featured Emeka Okafor (the second pick in the 2004 draft) and a random assortment of role players, none of whom had averaged double-figure scoring for their prior teams: Gerald Wallace, Primoz Brezec, Brevin Knight, Jason Kapono. Their most distinguished player was Steve Smith, who was 35 and months away from retirement.

The Bobcats won 18 games in their first season and averaged 29 wins in their first five years, finally posting a winning record (44-38) in year six. Later rechristened as the Hornets, the franchise has yet to win a playoff series in its 20 years of existence—in part due to mismanagement but also because it’s just really hard to build from scratch.

The then-22-year-old Wallace, an athletic small forward who’d been plucked from Sacramento in the expansion draft, didn’t help the Bobcats win much—but his departure was a serious blow to the Kings’ depth. Knight, Kapono, and Brezec were all useful role players elsewhere but unfit as everyday starters. That’s how it goes with expansion. Or, at least, how it went 20 years ago. Which, really, wasn’t much different from how it went for the Toronto Raptors and Vancouver Grizzlies after they joined the league in 1995. Both started miserably. And although the Raptors found modest success in their fifth year, behind a young Vince Carter, they won just one playoff series in their first 20 seasons. It took the Grizzlies nine years—and a relocation to Memphis—before they even made the playoffs, and another seven after that before they won a series.

It would surely be different today, right? The league is deeper. Players across the board are more skilled. Front office executives are collectively smarter. Every team today has player-development coaches to help speed up a prospect’s growth. The landscape is different. Better. Potentially more fruitful in Vegas and Seattle, too. More fertile for expansion and more conducive to a bad team getting better, sooner.

And yet there’s still this (seemingly) immutable reality: You need a superstar to win at a high level. You need second-tier stars to support the top-tier stars. Or you need a bunch of Robins to overcome the lack of a Batman. And, well, there still aren’t enough caped crusaders (either of them) to go around.

The NBA is now in an era of hyper-parity, engineered by a highly restrictive salary cap that almost forces the distribution of top talent. We’ve seen six different champions in six years. Superteams are practically defunct. The standings are tighter than ever. Maybe that makes it easier for the new teams to find their footing. Maybe this just furthers the parity. Maybe this is what the league wants.

Then again, maybe there are potential stars hiding in plain sight who just need the right situation—more minutes, more responsibility, more shots, a team of their own—to show they’re capable of bigger things. Maybe there’s another generation of LeBrons, Stephs, and KDs arriving in the next five years.

“We have incredible players in this league, with incredible skill level,” said another Western Conference exec. “I think the coaching continues to be at an elite level, and these front offices are very, very smart and do a very good job. So yes, I think, though it’ll take time for these expansion teams to get up and running, eventually, I would expect the league to be in a very healthy place.”

Who’s right? Who’s wrong? Is the skepticism warranted? What will actually happen when (if?) the league adds two new teams? There are no definitive answers, just hunches and estimates for now, until the league plants its flag in two new cities and, critically, gives those teams time to get their footing.

Can the NBA handle two more teams? Check back in 2035.