Nineteen seconds. That’s how long it took on my TV to switch from MrBeast’s channel on YouTube to Prime Video, type in “B,” and click on the suggested tile for Beast Games, the reality/game show created and hosted by the selfsame MrBeast. In less time than it takes Beast, née Jimmy Donaldson, to dispense some enormous sum of money, I navigated the divide between YouTube and traditional TV. (Assuming a streaming service owned by a Big Tech titan counts as “traditional.”)

I timed this transition not because I was worried about withdrawal setting in if I went too long without watching MrBeast but because I was wondering how high the YouTube-to-TV barrier is. Your time-to-Beast may vary: If you don’t use a smart TV, or your remote doesn’t have a Prime Video button, your MrBeast blackout period might stretch for a few more excruciating seconds. Then again, on a phone or computer, Beast transfer is almost instantaneous: Click the link to Beast Games anywhere on MrBeast’s channel, or below any of his individual videos, and you’re there. It wouldn’t take long for his fans to follow him across platforms.

And he has a lot of fans. MrBeast boasts 363 million YouTube subscribers, which makes him the most popular YouTuber by far. (That count keeps climbing fast: His subs stood at a scant 361 million when I started writing this piece.) His most-watched video, which documents a 2021 “Squid Game In Real Life” stunt that essentially served as a proof of concept for Beast Games, has been viewed more than 750 million times. The first two seasons of Squid Game itself, the most popular series in Netflix history, have combined for fewer than 450 million views. (“Views” are defined differently depending on the source, you say? Yeah, we’re going to get to that.) Surely, then, Beast Games must be an industry-disrupting smash for Amazon, which will accelerate influencers’ and YouTubers’ takeover of TV. Right?

“There’s always a twist,” Donaldson proclaims in the season finale. And the twist in this case is that Beast Games has merely done … decently, considering its sizable budget and expectations. “Amazon overpaid for it, given what they got,” Puck entertainment journalist Matt Belloni said last week on his Ringer podcast, The Town. Belloni’s guest, Netflix chief content officer Bela Bajaria, laughed as she responded, “You said it, I didn’t.” (Netflix also met with Donaldson about Beast Games, which Bajaria lightly derided to Belloni as “very much like Squid Game.”)

The industry has ample reason to scrutinize the reception to Beast Games, both as an indicator of Donaldson’s appeal beyond YouTube and as a possible bellwether of creator crossovers to come. YouTube, which turned 20 on Friday, has long since evolved beyond being a home for content consumed on phones and computers: In December, the company announced that viewers had streamed more than 1 billion hours per day of YouTube content on TVs in 2024. Earlier this month, YouTube CEO Neal Mohan revealed that “TV has surpassed mobile and is now the primary device for YouTube viewing in the U.S.” For the past two years, Nielsen has rated YouTube as the no. 1 streaming platform in the country; last summer, it outstripped all other TV distributors. In the fourth quarter of 2024, YouTube alone accounted for three-quarters as many hours streamed as Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, and Prime Video combined.

The performance of a single series isn’t really a referendum on the transmedia appeal of an entire entertainment ecosystem, but if any YouTuber-fronted project had the potential to be big, it was Beast Games. The series’ first season, which concluded last Thursday, was designed to be buzzy: a 1,000-person competition for a record $5 million prize (which ultimately grew to $10 million). Over 10 episodes, the field was winnowed via physical, psychological, and social stunts and tests, filmed from every angle and presented in a senses-assaulting style. Donaldson, 26, emceed, speaking internet-ese: “That would be legendary,” he said in response to one contestant’s stated goal of devoting his hoped-for windfall to a search for a cure for his sick son’s rare, untreatable illness. (Donaldson also called the contestant a GigaChad.)

If anything, Donaldson detracted from the spectator experience, with his shout-talking delivery, fixed smile, and retinue of black-clad bros who roamed around the series’ sets, hyping up the proceedings like Bob Nastanovich at a Pavement show. The true star of the series wasn’t Beast or the contestants but the scale of the production, from the centerpiece set, “Beast City,” to the trap doors that plunged the losers into what appeared to be bottomless chutes.

All of that spectacle cost a nine-figure fortune. “On this show, I have unlimited money to give away,” MrBeast bragged in the first episode, before testing that contention by making it rain to the tune of roughly $25 million overall. “In case you’re wondering, yes, this show is way over budget,” he joked(?) in the finale, in a “how it started/how it’s going” contrast.

Beast’s ambitions also had a human cost: Last September, following a lengthy New York Times report about problems that plagued the production, five contestants announced that they would sue Donaldson and Amazon over what they said were unsafe and toxic conditions during the making of the show. “We really need a hit, so they just let him do whatever,” an “Amazon insider” told Business Insider last August, as various controversies surrounded the star: the resurfacing of racist and homophobic comments Donaldson made as a teen; reports about the culture of his company that eventually prompted an internal probe and firings for “workplace harassment and misconduct”; even allegations that some of his snack kits contained mold. That swirl of scandals extended Donaldson’s history as a hot-button figure who’s engendered debate about his polarizing screen presence, single-minded pursuit of virality, and embrace of a brand of performative philanthropy that strikes some as prosocial and others as exploitative.

There’s certainly something dystopian about Beast Games, even sans Squid Game’s lethality. (And also stripped of the moat Donaldson and Co. planned to build around Beast City, before they “ran out of time.”) Of course, there’s also something dystopian about Amazon, which clearly craved Donaldson’s audience. Beast Games, Belloni tells me via email, “was pitched to all the streamers and Amazon paid around $100m for it, far more than Netflix was willing to offer. Despite the audience, it still feels like a bit of a disappointment to me. I think it hurt that Beast couldn’t really do a lot of mainstream promotion because he didn’t want to be asked about the allegations of an unsafe production. That said, Amazon says they are happy with the show and look forward to doing more.” No renewal has been announced.

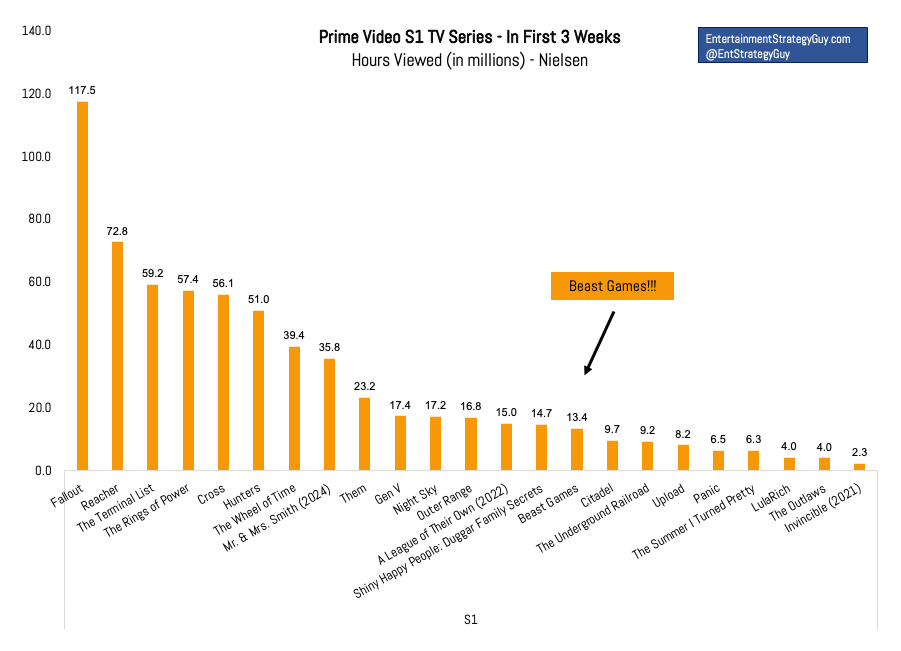

If Amazon really needed a hit, did it get one? According to the Entertainment Strategy Guy, a former network executive who analyzes entertainment industry data at The Ankler and on Substack, not really. As the ESG wrote in January, “this show is not a hit—no matter what data you look at or how you cut it—but it also isn’t a flop or bomb.” Beast Games missed the Nielsen charts in its first week before subsequently ranking toward the bottom of the top 10, with modest totals of around 7 million hours watched per week. Beast Games also received so-so results from alternate viewership trackers Samba TV and Luminate; no-showed on interest charts from JustWatch, Reelgood, and TV Time; and garnered middling Google search traffic and lackluster user review counts and scores at IMDb and Prime Video. (Few critics reviewed it, and those who did were harsh.)

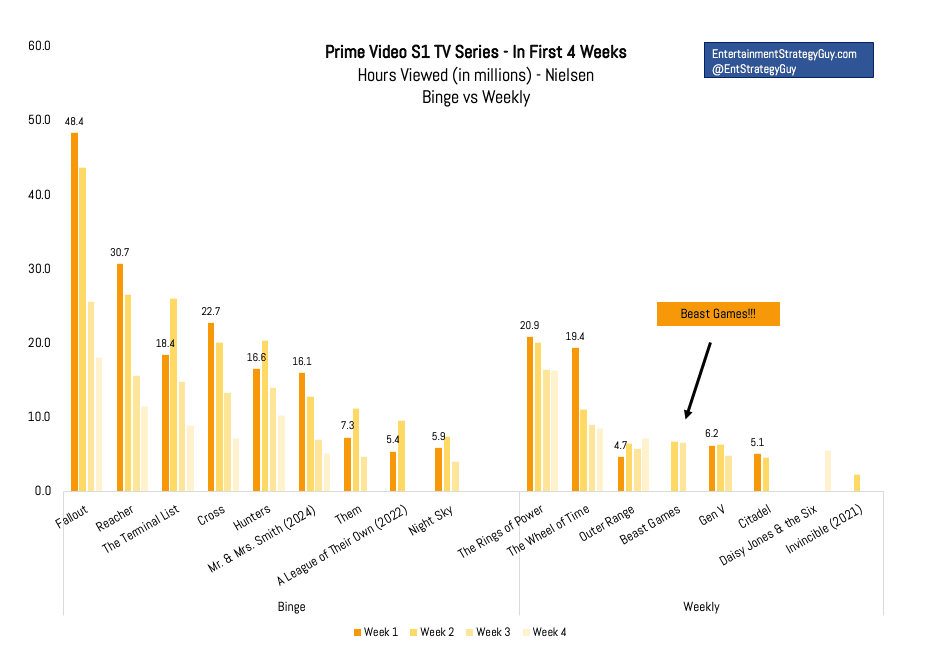

Amazon trumpeted that Beast Games attracted 50 million “viewers” (which the company doesn’t define) in its first 25 days. But Prime Video’s heavy hitters have easily surpassed that pace. Red One reached that total in three days; Season 1 of The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power reached 25 million viewers in its first day, and 100 million in three months; Season 2 of Rings of Power reached 40 million viewers in 11 days; and Fallout reached 65 million viewers in 16 days. Two charts published by the Entertainment Strategy Guy make clear that Beast Games didn’t get off to an especially strong start by Prime Video standards, even compared to previous weekly releases. It’s been about as popular as Outer Range (which was canceled after two seasons), and a lot less popular than The Wheel of Time.

Beast Games fares better in relation to other competition shows, albeit nowhere near Netflix behemoths such as Love Is Blind, Perfect Match, The Circle, or—perhaps the closest comp in terms of subject matter—Squid Game: The Challenge. However, Beast Games has a much bigger budget than most shows in its genre. And as the ESG noted, “Amazon put a LOT of owned marketing and on-site advertising behind Beast Games. That gives it an advantage few other shows have.”

On the positive side, the ESG adds via email, the viewership for Beast Games “has held really well, though at a low level.” (That is, while its audience wasn’t enormous, it didn’t shed the viewers who gave it a chance.) Amazon said the series is its most “acquisitive” since Fallout, signifying that new customers have subscribed just to see it (and, in the process, given Amazon valuable new data about their buying behavior). The show travels well, too: Per Amazon, about half of its audience is outside the U.S. But based on the latest data, the ESG concludes that Beast Games is “still not a hit, and probably not a hit for Amazon either, though maybe in 2024 it [was] one of their better shows.” Hence what both Belloni and the ESG label a “disappointment”: Given Amazon’s investment, the ESG wrote, Beast Games would have had to do “really, really well” to qualify as a success.

So why didn’t MrBeast’s unmatched YouTube subscriber count propel Beast Games to the top of the TV heap? And if his TV debut didn’t truly break through, what might that mean for the TV viability of other online creators?

One factor holding Beast back is the financial barrier to entry. Although MrBeast essentially put a pilot for Beast Games on his channel in December, providing a perfect on-ramp for his viewers, they still had to have access to Prime Video to keep watching. YouTube is free and can be watched without a subscription; Prime Video requires viewers to sign up for something. Granted, almost 200 million people in the U.S. subscribe to Amazon Prime, which includes access to all of Prime Video, including Beast Games. Plus, Amazon offers free trials for Prime Video, and Beast Games is also available on Amazon Freevee. Even so, some YouTube viewers probably abide by an oft-cited self-defense maxim: Never go to a second location. No wonder MrBeast uploaded the full first three episodes of the series to his second YouTube channel last week; if he hooks viewers there, he could convince them to overcome their resistance to streaming elsewhere.

Even if MrBeast converted all of his YouTube watchers to TV watchers, the resulting ratings would likely be lower than his subscriber count (or the 159 million views of his video prelude to Beast Games) would suggest. Both of those figures are inflated, because a lot of internet traffic is fake—both in the sense that some of it is bot-driven and in the sense that companies tend to put the most positive possible spins on their audience sizes. YouTube doesn’t divulge its definition of a “view,” but many sources assert that only 30 seconds of screen time counts as a view—whereas Netflix, since 2023, has calculated “views” by dividing a release’s total time spent watching by its running time. The Entertainment Strategy Guy has previously written that he “heavily discount[s]” YouTube views compared to domestic TV streaming views, assuming that 50 percent of the former come from outside the U.S., that 50 percent of the remainder come from bots, and that most non-music videos are watched for only a few minutes.

On Substack last month, the ESG laid out what he labeled “one of the big mysteries of the streaming era: If YouTube stars really can command a devoted audience of 100-plus million fans, why aren’t the streamers hiring them or buying their shows?” The mystery was mostly solved later in the same story: “Social media/social video/YouTube followers are not converting to legacy media channels.” Beast Games proves the point. The ESG estimates that only 12 million people worldwide truly took in each Beast Games episode—a single-digit percentage of his subscribers, which is consistent with the typical percentage of people who are willing to pay for other content they enjoy. (In other words, we’re all a bunch of freeloaders.) “I’d say this shows how many dedicated fans [360-plus] million global subscribers actually translates to,” the ESG tells me.

Finally, even if people are spending billions of hours on YouTube on TVs, what they’re watching may not look like (or come out on the same schedule as) traditional television. “The ‘new’ television doesn’t look like the ‘old’ television,” YouTube CEO Neal Mohan wrote this month. “It’s interactive and includes things like Shorts (yes, people watch them on TVs), podcasts, and livestreams, right alongside the sports, sitcoms, and talk shows people already love.” When Bajaria told Belloni that “MrBeast is a great talent on YouTube,” it sounded more like a neg than an endorsement: YouTube talent doesn’t guarantee greatness at delivering what more traditional TV viewers want. On the other hand, one critique of Beast Games is that it’s too TV-like, a quality that might turn off his YouTube faithful while also preventing the series from standing out on streaming. As Kotaku’s John Walker wrote, “The editing feels like TV. The camera work feels like TV. The presentation, the events, the obligatory confessionals with individual players, all just TV.”

MrBeast understands these distinctions as well as anyone. In an undated document about how to succeed at his company that was leaked last year, Donaldson wrote, “This is not Hollywood and I do not want to be Hollywood,” and advised his employees to “Get rid of Netflix and Hulu and watch tons of YouTube.” Perhaps his ambitions have broadened, but maybe that instinct to stay in his lane was smart. “99 percent of movies or TV shows would flop on YouTube,” Donaldson wrote. Why shouldn’t the inverse be true?

To date, it largely has been. Charli D’Amelio, the second-most-followed TikTok creator—ahead of the ubiquitous MrBeast, who ranks third—had a Hulu reality show, The D’Amelio Show. It ran for three seasons prior to its cancellation last year but didn’t draw large audiences. Neither has The Kardashians, the Hulu successor to Keeping Up With the Kardashians, which ran for 20 seasons on linear TV. In 2023, the Entertainment Strategy Guy classified both shows as flops, writing, “At most, a few million people watch either show. That’s a conversion rate of ‘social media followers to Hulu viewers’ of about .001 percent. … Either social media isn’t real life (and TikTok stats are incredibly inflated, by orders of magnitude) or Hollywood will never get crossover appeal from social media stars.”

Business Insider reported last month that “streaming services and studios have been on the hunt for influencer-fronted content.” Two BI articles documented recent reversals in streamers’ receptiveness to projects built around internet celebrities—mostly of the unscripted, personality-driven variety—and forecasted further high-profile creator-to-TV leaps. Beast Games certainly won’t be the last of its kind, but the Entertainment Strategy Guy cautions studios against going all in, likening a MrBeast-driven feeding frenzy to what he terms the “Taylor Swift phenomenon”: the notion that Taylor Swift’s record-setting 2023 concert film would usher in a wave of similarly lucrative successors. Instead, subsequent films or specials—even those featuring megastars such as Beyoncé and Olivia Rodrigo—generated nowhere near as much interest. Swift was one of one, and Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour didn’t open the blockbuster-concert-film floodgates any more than The Last Dance did for sports documentaries.

Donaldson is the Swift or Michael Jordan of YouTube, so it’s risky to extrapolate from him. “The worry is if MrBeast is the biggest YouTuber/TikToker, then everyone else will be smaller by definition,” the ESG says via email. Thus, as he wrote last month, if “Beast Games is at best a mid-tier show,” then “other shows will be small to non-existent.” If Donaldson, D’Amelio, and the Kardashians can’t go TV-viral, what hope is there for the likes of Influenced, A Little Late With Lilly Singh, or Ryan's World the Movie: Titan Universe Adventure?

Even decades into the era of smartphones, social media, and YouTube, there remains a deep divide between internet fame and offline awareness. (As evidenced by my wife wondering who MrBeast was when I put on the premiere of Beast Games, or the dismay many basketball watchers experienced on Sunday, when MrBeast not-so-briefly seized the spotlight at the NBA All-Star Game.) To live online is to constantly encounter creators you’ve never heard of who have huge followings; as one recent, well-circulated tweet observed, “There are entire worlds existing in parallel to yours about which you know nothing.” The so-called “creator economy” may be growing rapidly, but on the whole, it’s still small—and TV studios would probably be wise to stay selective.

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos noted last month that while “the short-form services” are competitors to his company, they “also are a great breeding ground for new storytellers” that Netflix can mine for material. But Bajaria told Belloni that while there are “creators out there doing really cool, interesting things,” she’s mindful of “what makes sense for Netflix,” which she described as “the home for premium, professionally made film and TV.” She also downplayed a recent report that Netflix is courting video podcasters, saying, “Anytime we have a meeting or a conversation, it’s written about like it’s something that we’re changing our strategy. And that’s very overstated.”

In some respects, these opportunities and pitfalls aren’t new. Hollywood has long looked to the internet for inspiration and profit, with some successes (web series adapted into cult favorites like Letterkenny or Broad City) and the odd disaster (Disney’s ill-fated acquisition of YouTube network Maker Studios). These adjacent new and old media markets are already tightly intertwined: Late-night TV shows rely on YouTube for attention, follower counts dictate casting decisions for films and TV series, and studios promote projects via streamers and metaverse-style video games.

As TV audiences age, YouTube’s all-ages ad revenue skyrockets along with its market share, and creators collectively earn more money from YouTube than from Disney or Netflix, these ties will tighten further. The best approach for studios, the Entertainment Strategy Guy tells me, “is to not overpay, and focus on fundamentals: make great shows with good concepts/execution, and the talent adds to it. But if the talent needs to sell it, then you’re looking at diminishing returns.”

This strategy may manifest in Netflix partnering with my daughter’s favorite YouTuber, Ms. Rachel, or YouTubers Dude Perfect raising capital and attempting to form a multimedia empire. Maybe it looks more like ESPN leveraging Pat McAfee’s YouTube-boosted audience to anchor its midday programming, or news networks eyeing influencers. Maybe it’s content-sharing arrangements such as British broadcaster ITV’s recent deal to license shows like Love Island to YouTube, or various studios’ arrangements with Gaggl, a platform where internet personalities can host TV watchalongs with their communities. Maybe it’s FAST-growing free, ad-supported streaming services such as Tubi continuing to woo their young audiences with influencer-focused films.

All of this reminds me of the much-ballyhooed battle between statheads and scouts in baseball, which intensified after Moneyball became a bestseller. At the time, this struggle seemed existential, but there is no conflict now. The scouts started using stats, the statheads started quantifying what was traditionally considered scouting info, and teams embraced all forms of intelligence, which led them to invest in both stats and scouts.

Now, YouTube creators are filming in 4K and boosting their production values, even as cost-cutting streamers have leaned toward lower-budget productions rather than pricey prestige fare. The likeliest outcome is that distinctions break down as the delivery vectors merge. When cord-cutting is complete, TV makers structure shows around never-ending second-screening, and Gen Z and Gen Alpha rule the roost, how much will audiences distinguish between one app and another, or among influencers and different flavors of creators? After all, what does “mainstream” mean anymore? What constitutes “quality”?

Maybe the core question is whether YouTubers need TV streamers and networks more than the streamers and networks need YouTubers. Or maybe necessity is beside the point. “YouTube doesn’t need to grow into other spaces it doesn’t already dominate,” Julia Alexander wrote in January, but to pass up potential growth “would deny the foundations” of contemporary capitalism. Why would creators specialize in new TV or old TV if they could be bigger on both? When YouTubers The Sidemen signed with Netflix last November, Vik “Vikkstar123” Barn explained that the group hoped to “reach a new audience” and “connect with different people,” because it had hit “a ceiling with YouTube.”

Nobody’s YouTube ceiling is loftier than MrBeast’s, but it’s still not high enough for him. “My goal is to make the greatest show possible and prove YouTubers and creators can succeed on other platforms,” he said when his show got green-lit. Neither of those missions has been accomplished quite yet.