How to Build a Competent NBA Expansion Team in 10 Not-So-Easy Steps

We analyzed the successes and failures of expansion clubs throughout North American sports history. Here’s our advice to the next franchise that joins the NBA.It’s NBA Expansion Week at The Ringer! With a break in the schedule, we’re examining one of the biggest questions about the future of the league: Should the NBA expand beyond 30 teams? We’ll examine all the possibilities and complications, plus take some strolls down memory lane and examine some expansion teams of the past. We’ll bring it home at the end of the week with a hypothetical mock draft and a deep dive on potential future team owners.

Rick Sund’s first big executive role in the NBA would have been hard enough as it was. Running a team is a tough, competitive job, and in 1979, Sund became the youngest exec in the league when the Dallas Mavericks hired him as their director of player personnel as a mere 28-year-old.

But Sund’s youth wasn’t even the most challenging aspect of his job; that was the state of his team. The Mavericks were an expansion franchise and Sund was in charge of building their first roster. To prepare, he spent a year scouting college and professional games. He studied the history of previous expansion teams. And he consulted with GMs and coaches throughout the NBA “to basically find out the good, the bad, and the ugly of being a basketball executive with the expansion clubs.”

All of that prep work led Sund to a simple conclusion: The Mavericks’ immediate future was dire. “I knew no matter what happens,” he recalls thinking, “we’re going to have the worst record in the league.”

He was right. The Mavericks went just 15-67 in their maiden season, six games worse than any other team in 1980-81. Call it growing pains: NBA expansion franchises have been uniformly terrible throughout history. The next expansion teams after Dallas—the Heat and Hornets, in 1988-89—were the two worst teams in the league. The most recent expansion squad, the 2004-05 Bobcats, managed a bit better—they tied for only the second-worst record as NBA debutantes.

It’s that kind of consistently brutal start that inspired the best quote about starting a sports franchise, from the Cavaliers’ inaugural coach, Bill Fitch, in 1970. “War is hell, but expansion is worse,” Fitch said.

But other sports leagues show it doesn’t have to be. In hockey, the Vegas Golden Knights (established in 2017) reached the Stanley Cup final in their first season and lifted the trophy in their sixth. In baseball, the Arizona Diamondbacks (est. 1998) won 100 games and a division title in their second season, then celebrated a memorable championship in year four. Even in a different basketball league, the WNBA, the expansion Atlanta Dream (est. 2008) reached three Finals within their first six years.

That level of instant success might not be achievable in the NBA, as stars dictate outcomes in basketball more than in any other sport, and stars are extremely difficult for expansion franchises to acquire. But prospective NBA teams aren’t predestined to end up like the Bobcats, who still haven’t won a postseason series two decades after their inception, or like the expansion Grizzlies, who had already moved from Vancouver to Memphis before they ever reached the playoffs. Sund’s Mavericks were in the conference semifinals by year four.

Whenever the NBA’s next expansion teams arrive, it should take lessons from the most successful expansion squads across American professional sports. Here is a 10-step plan, based on their experiences, to—in a twist of Fitch’s words—climb out of hell as quickly as possible.

1. Accept that you’re going to be horrible for the first few seasons.

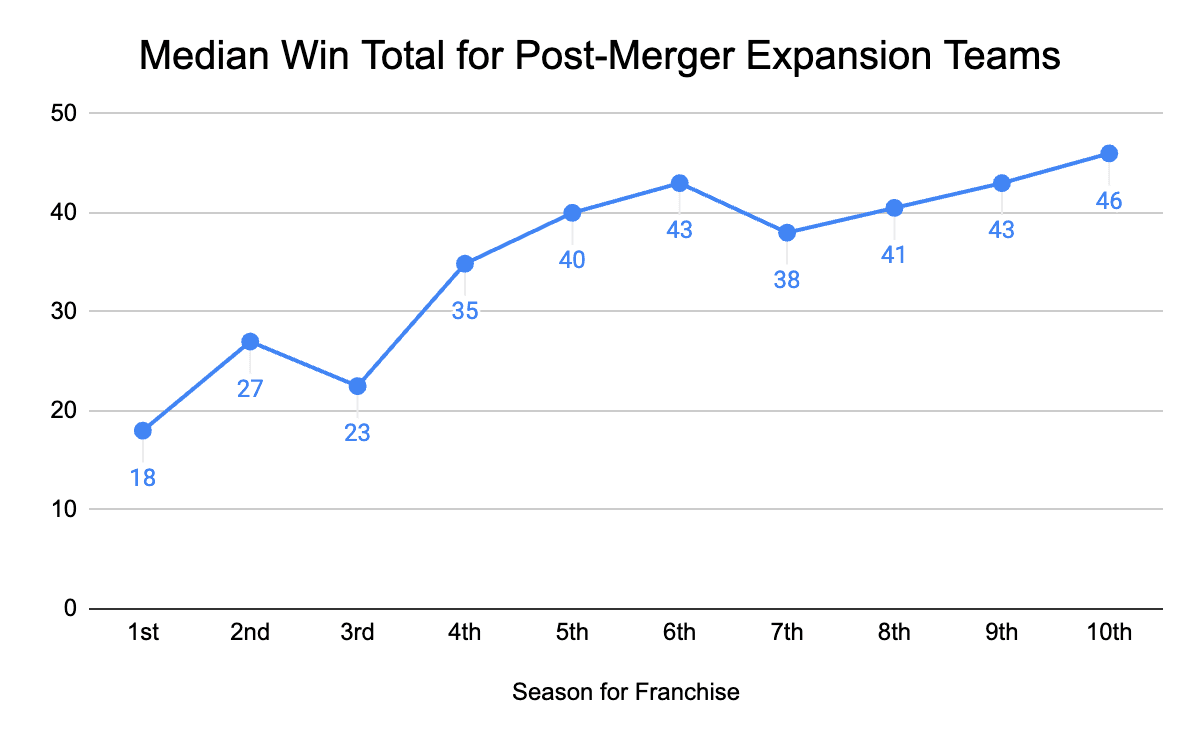

Let’s start by copying one of Sund’s first moves as an executive and turn toward history, by analyzing the eight expansion teams since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976. All eight of those teams joined after the introduction of the 3-point line, and they all had the same expansion draft rules, so they’re on an even footing for comparison purposes. We can probably expect the next NBA expansion to operate in a similar fashion.

Their early results aren’t pretty. All eight expansion teams lost at least 60 games in their first season. All eight lost at least 50 games in their second season. And all eight lost more than half their games in their third season.

It took four years for any of these squads to finish with a winning record or reach the playoffs, and it took five years for any of them to win 50 games. In other words, history suggests it will take half a decade at best to approach real contender status.

Setting realistic expectations for the early seasons can lessen the sting of all those losses. It can also dampen the desire for short-sighted transactions, like the Vancouver Grizzlies’ ill-fated trade for 35-year-old forward Otis Thorpe after their second season. The Grizzlies were terrible without Thorpe, and they were terrible with him—but they ended up giving the Pistons the no. 2 pick in a loaded 2003 draft for his services.

Building slowly can make it easier to demonstrate progress, as well. As Sund remembers telling Dick Motta, the Mavericks’ inaugural coach, “‘Dick, I don't care if we only win 15 games. So what? … Then that means next year we only have to win more than 15.’ Every year that you win more than you did the year before, you’re building capital with your fans.”

2. Don’t count on the expansion draft to save you.

The prospect of an expansion draft is catnip for NBA nerds. When the next one arrives, expect a flood of blogs, podcasts, and other fodder about which players will be protected, picked, and packaged in trades.

But an expansion draft isn’t actually built to help new teams find franchise cornerstones. Existing teams can protect eight players on their roster, which leaves very little talent for the expansion squads to sift through. In a star-driven league, albeit one that’s deeper than ever, how many ninth and 10th men are really potential difference-makers?

Not many, according to the results of the expansion drafts since the merger. Only 49 percent of expansion draftees ever played for the team that picked them. And only 18 percent appeared in more than 82 games with that team. In other words, fewer than one in five players taken in an expansion draft spends more than a single season with their new franchise.

And forget about landing a legitimate star. As Joe Garagiola Jr., the inaugural general manager of MLB’s Diamondbacks, says of the whole expansion draft process, “Don’t go into it with any illusions that you’re going to be able to draft an elite-level player.”

Since 1980, 114 players have been picked in NBA expansion drafts, and they’ve combined to make a grand total of one All-Star appearance with their new team, courtesy of Gerald Wallace with the Bobcats. A couple of others won awards—Dell Curry was a Sixth Man of the Year for the Hornets, and Scott Skiles was named Most Improved Player for the Magic—but none were stars.

Highest-Scoring Post-Merger Expansion Picks

An enterprising expansion GM might dream about discovering some hidden talent in the draft, and turning another team’s trash into a new city’s treasure. But even in a best-case scenario, he’s far more likely to end up with a couple of decent role players than an actual face of the franchise. Still, that doesn’t mean the expansion draft can’t help you in other ways.

3. Instead, use the expansion draft to exploit other teams.

“Nobody believes in us” is a tired sports cliché, but when the Vegas Golden Knights joined the NHL in 2017, it was actually true. They were 500-to-1 longshots to win the Stanley Cup in their debut season, with the league’s lowest projected point total. In retrospect, however, Vegas enjoyed the best expansion draft in recent sports history—but not just because they found a colossal cache of diamonds in the rough.

“One of the biggest reasons the Golden Knights did so well in the expansion draft is not so much the players they picked,” says Jesse Granger, a reporter for The Athletic who has covered the team since its inception, “but the way they used the situation to hold the other teams over the fire a little bit.”

Vegas’s strategy was essentially to turn the expansion draft into a protection racket. That’s a nice unprotected player you’ve got there, they’d tell another team. Sure would be a shame if you lost him in the draft. But then instead of drafting that player, the Golden Knights would offer to pick a less valuable player in exchange for other assets.

For instance, they agreed to pick an injured player from the Anaheim Ducks, Clayton Stoner, instead of more coveted defensemen—as long as the Ducks sent them recent first-round pick Shea Theodore in return. Eight years later, Theodore is the Golden Knights’ franchise leader in assists. That same approach led to 10 different trades around the draft, meaning the Golden Knights found such deals with a third of the league.

This strategy has NBA precedent, as well. In the 1988 expansion draft, the Miami Heat had the first pick and selected Arvid Kramer, a 31-year-old center with just eight career NBA games under his belt, all of them back in March 1980. “Miami Chooses ‘Who?’ First,” a New York Times headline announced.

But the Heat had a reason for this ostensibly odd choice: The Mavericks offered Miami their first-round pick in the “actual” draft that year if the Heat picked Kramer, whose NBA rights belonged to Dallas—instead of the more appealing players that Dallas hadn’t had room to protect. Thus the Heat were able to nab a college prospect by threatening to poach a player the Mavericks wanted to retain.

Miami also accepted extra picks from the Lakers (for not taking the unprotected 41-year-old Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), Celtics (for not taking Dennis Johnson), and SuperSonics (for not taking Danny Young).

The next NBA expansion teams should seek to make use of this approach with a team like Oklahoma City, which has tremendous roster depth and oodles of extra picks. If an expansion draft were held this summer, the Thunder might offer one of their many upcoming first-rounders so a new expansion team wouldn’t steal a key reserve from the budding juggernaut.

4. Value real draft picks more than expansion picks.

The Heat’s selection of Kramer meant they essentially traded an expansion pick for a pick in the real draft. Given the observed odds of an expansion pick developing into an All-Star (1 in 114), that seems like a lopsided trade.

But Miami had nothing on what Sund accomplished with Dallas. Before the 1980 expansion draft, the Mavericks used a different tactic to achieve the same goal: Leverage the expansion draft to collect as many actual draft picks as possible.

Unlike Miami, the Mavericks didn’t hold any unprotected players hostage, so to speak. Instead, Sund says, Dallas’s expansion draft philosophy was, “Hey, we're going to be bad no matter who we get in the expansion draft. … But what we would do is we really focused on players that might have sex appeal for other teams.”

Sund recalls receiving other teams’ lists of protected players the night before the expansion draft and immediately going to work. He and his boss, Norm Sonju, “met with almost every GM between the time we got the list until like 2 in the morning to see if we could strike any deal, and we'll draft the player for you.”

The result was a dizzying number of trades, all returning future picks to Dallas. The Mavericks chose young forward Wiley Peck, then traded him to Phoenix for a second-rounder. They picked point guard Billy McKinney, then dealt him to Utah for two seconds.

And most famously, over the course of three separate trades with the Cavaliers in 1980-81, the Mavericks acquired first-round picks in 1983, 1984, 1985, and 1986 in exchange for players they’d taken in the expansion draft. That level of exploitation eventually landed Derek Harper, Sam Perkins, Detlef Schrempf, and Roy Tarpley in Dallas, and inspired the creation of the Stepien Rule, which prevents teams from trading their first-rounders in consecutive drafts.

It’s easy to imagine this sort of deal making sense during the next NBA expansion draft. Would a player like, say, CJ McCollum have any value to an expansion franchise that can’t conceivably compete for a few years? No. But if the Pelicans preferred to protect their younger building blocks ahead of McCollum, an expansion team could canvass the league to determine McCollum’s market, then pick and trade him to a win-now squad in exchange for more draft capital.

5. Take advantage of the novelty.

Modern-day NBA GMs are too smart to trade multiple unprotected first-round picks for role players, as Stepien and Cleveland did in the early ’80s. But that doesn’t mean every chief decision-maker would handle an expansion situation perfectly. More than two decades have passed since the NBA last expanded, and so much about the league—the 3-point boom, new financial rules, player empowerment, and so on—has changed in the interim. There’s no clear set of strategies for the non-expansion teams to pursue, and without recent precedent, new opportunities may arise.

That context helps explain why the Golden Knights were so successful in the NHL’s first expansion draft in 17 years. “It hadn’t been done in a very long time. Most of the GMs that were in their jobs at the time had never gone through an expansion, so they weren’t prepared for it,” Granger says.

By the time the expansion Seattle Kraken joined the NHL four years later, the rest of the league had learned from its mistakes. “Seattle gets here, [the GMs] all saw how they got burned against Vegas,” Granger says. “So if you look at the Seattle draft, there’s almost no trades. And that really hurt the Kraken, because they weren’t able to build up that cupboard of draft picks and prospects that Vegas was right away.”

6. Land a no. 1 pick.

OK, this one’s obvious—of course a no. 1 pick is a valuable prize—but it seems like the most important factor when analyzing how past NBA expansion teams have made the leap to competitiveness.

The Magic shot up from 21 wins in their third season to a 41-41 record in year four and a Finals trip in year six, after drafting Shaquille O’Neal first overall. The Hornets quickly reached the playoffs and won a series after drafting Larry Johnson (first) and Alonzo Mourning (second) in consecutive years. And the first time the Mavericks reached the playoffs, no. 1 pick Mark Aguirre ranked second in the league in points per game.

In the WNBA, meanwhile, the Atlanta Dream lost their first 17 games and finished 4-30 in their inaugural season. But they were league finalists by their third season, in large part because no. 1 pick Angel McCoughtry developed quickly into an All-WNBA star.

Because of the limitations of the expansion draft, a no. 1 pick is the only possible get-rich-quick scheme for an expansion basketball team. Granted, it could be a harder scheme to execute now, given that the NBA’s flattened lottery odds penalize the league’s worst teams. But an expansion team’s first few seasons of nearly guaranteed losses still mean a nearly 50-50 chance of landing at least one no. 1 pick, and a majority chance of landing a top-two selection.

Probability of a Top Draft Pick With Current Lottery Odds

And while the flattened odds hurt, it could be worse: Expansion teams in the ’90s weren’t even allowed to win the lottery for their first few seasons. The ping-pong balls actually favored the Raptors in the 1996 lottery, but the rules dropped Toronto to the no. 2 pick and Marcus Camby. The 76ers jumped up to the first pick in the Raptors’ stead and selected Allen Iverson.

7. Use your cap space to get—all together now—more picks.

Expansion franchises are limited in all sorts of ways as they build out their rosters. But they also have one unique point of freedom: a clean cap sheet, with no high-dollar deals clogging their future books.

This flexibility gives expansion teams a meaningful advantage in trade negotiations, as they can serve as a metaphorical dumping ground for other teams’ financial mistakes. In the NHL, the Golden Knights made use of their initial cap space as they “took a ton of bad contracts,” Granger says—in exchange, of course, for a “bushel of draft picks.” In the most important of those deals, Vegas agreed to trade for the hefty contract of David Clarkson, who was injured and would never play in the NHL again; in return, the Golden Knights received first- and second-round picks. They also agreed to select unheralded center William Karlsson in the expansion draft, instead of one of his more prominent unprotected teammates.

But Karlsson broke out right away in Vegas; he’d never scored double-digit goals in a season before, but tallied 43 in his first campaign as a Golden Knight. He now ranks second in franchise history in goals and assists, and all Vegas needed to do to acquire him along with valuable picks to fill in some of its copious cap space.

This path is also open to NBA squads. In 2004, the Suns sent the Bobcats a first-round pick and $3 million to draft Jahidi White in the expansion draft and take his contract off their hands. Especially in the current NBA’s tight cap environment, thanks to strict apron rules, this route would seem a lucrative one for the league’s next expansion teams: Agree to take on a max salary that’s gone sour, and add to their growing pick stash in the process. Would the Trail Blazers trade an expansion team a future first-rounder to shed Deandre Ayton’s contract, for example?

8. Or spend to show you’re serious.

Let’s talk about another successful new team, which demonstrated a different way to use money to get better quickly: the Arizona Diamondbacks, who were part of MLB’s most recent expansion in 1998. The Tampa Bay Devil Rays joined the majors at the same time as Arizona and lost at least 90 games in each of their first 10 seasons, until a miraculous turnaround in year 11. But Arizona was a division champ by its second season and a World Series champ by year four.

The Diamondbacks mostly got there by flexing the power of the dollar. They went 65-97 in their debut season, but accelerated their competitive timeline with a spending spree the next offseason. They signed a fleet of free agents, most notably ace pitcher Randy Johnson and All-Star center fielder Steve Finley.

Johnson’s four-year, $52.4 million deal made him the majors’ second-highest-paid player at the time, and the Diamondbacks as a whole had a top-10 payroll by their second season and maintained a top-10 ranking for half a decade. But Johnson was more than worth it, winning the NL Cy Young Award four years in a row and splitting World Series MVP honors in 2001. Arizona’s overall spending was worth it, too: From 1999 through 2002, the Diamondbacks won the second most games in the National League.

The Diamondbacks’ splurges also created a virtuous cycle. One attractive free agent signing can beget others, if the first convinces the market that this expansion team is for real.

Initially that winter, remembers Garagiola, the Diamondbacks’ GM at the time, Finley had indicated that the Diamondbacks weren’t the right team for him. But “then after we signed Randy, we get a call back from [Finley’s] agent saying, ‘Hey, Steve called me and said, “If there’s any way to figure something out with the Diamondbacks, I want to be there.”’”

This brand of domino effect could certainly occur in the NBA, where agents, players, and front offices often collu—er, conveniently coordinate to facilitate superstar team-ups.

Granted, past NBA expansion teams have been financially restricted for their first couple seasons; their salary cap is only 66 percent of every other team’s in the first year, and only 75 percent in year two. But that would still leave enough room to take on some bad contracts for picks, or to start the process of signing big free agents—especially if the place is an attractive destination. Speaking of!

9. Emphasize local advantages.

Arizona might have been a new MLB franchise with no history or pedigree, but it benefited from a key contextual factor: Half the league plays spring training in the state, so players are used to living there for part of the year. The Diamondbacks were able to attract Randy Johnson in part because he had a house nearby. And Garagiola says the same was true for All-Star third baseman Matt Williams, who asked for a trade to Phoenix “for family-related reasons.”

For NBA players, a city like Las Vegas could immediately join the likes of Miami and Los Angeles as a premier free agent destination—especially if its team carries the prestige that would come from having LeBron James as a part-time owner, as has long been rumored. “I feel like if an NBA team were to come to Vegas, they’re going to be really good, really fast,” The Athletic’s Granger says. “In the NBA, you can completely change the look of a team with a couple signings. And what the Golden Knights quickly realized was players love playing in Vegas.”

Athletes in Vegas have access to all manner of nightlife options. They can play golf year round. They have an easy time getting to the airport. And, crucially, they don’t have to pay any state income tax in Nevada.

They also might end up with a rabid fan base in an emerging pro sports market. Granger points to the popularity of the UNLV Runnin’ Rebels—“the biggest team in town for forever, before the Golden Knights”—as evidence that Vegas is a basketball town at heart, to say nothing of the sport’s more recent incursions in the city, via summer league, Team USA exhibitions, the rise of the WNBA’s Aces, and the NBA Cup. “An expansion team for basketball coming to Vegas, I think they’re going to do incredibly well in terms of building a fan base and having diehard fans,” Granger says. “Basketball is ingrained in the culture of Las Vegas, probably more than any other sport.”

The same is also true of the NBA’s other most likely expansion city, Seattle, which has mourned the loss of the SuperSonics for nearly two decades. Over the last three years, Seattle residents have filled a sold-out arena for preseason NBA games. The excitement when a Seattle-based team returns for good could be enough to set off Mount Rainier.

10. Know it’s going to be really, really hard.

If the next NBA expansion squad follows all of these guiding principles, it will be in good shape to build a contender from scratch—but the actual construction process should still prove arduous. Only three expansion teams since the NBA-ABA merger have won championships, and it took those teams 18 years (for the Heat), 24 years (for the Raptors), and 31 years (for the Mavericks) to triumph.

By their very nature, it’s a lot easier for expansion teams to pile up losses than wins. Since 1980, the Heat (ninth) and Mavericks (12th) are the only expansion franchises that rank in the top 20 in overall winning percentage, while the Raptors (21st), Magic (22nd), Pelicans (23rd), Grizzlies (24th), Hornets (27th), and Timberwolves (30th) all rank among the bottom 10.

To make matters even worse, quickly transforming a new NBA franchise into a winner could be even harder now. For one, anti-tanking measures have made it more difficult for the league’s worst teams to build through the draft. After their first season, the Mavericks had a 50-50 chance to win the no. 1 pick, because in the pre-lottery era, the NBA determined the first drafter with a coin flip between the worst teams in each conference. Now, they’d have only a 14 percent chance at the no. 1 pick following a last-place finish.

Moreover, Sund says, one-and-done prospects are more challenging to scout than Mavericks draftees like Aguirre and Perkins, who stayed in college for three or four seasons. “You had a better feel of who these players are, back in those days. Today, it's so much more difficult,” Sund says.

Asked if he thinks he was lucky to be an expansion team’s executive back in the ’80s, as opposed to now, Sund quickly agrees. He even imagines that a slow-starting expansion team would face much more pressure now than his Mavericks did in the early ’80s, when social media didn’t exist and the NBA was only beginning to develop into a top-tier sports league.

Of course, today’s NBA is a massive, global enterprise full of celebrities, drama, and thrilling athletic spectacles. Fans in the next expansion cities will have plenty of reasons for excitement. It just might take a while before winning games is one of them.