There it is, a five-second video of LeBron James dunking a basketball. Is it a highlight? I guess, though in an age when highlights are ubiquitous, it’s just one more. James jolts toward the rim, takes a hard dribble, rears back, and slams it over a resigned defender. The play occurred during a regular-season game; he does this all the time. Few remember this highlight. And yet it’s infamous.

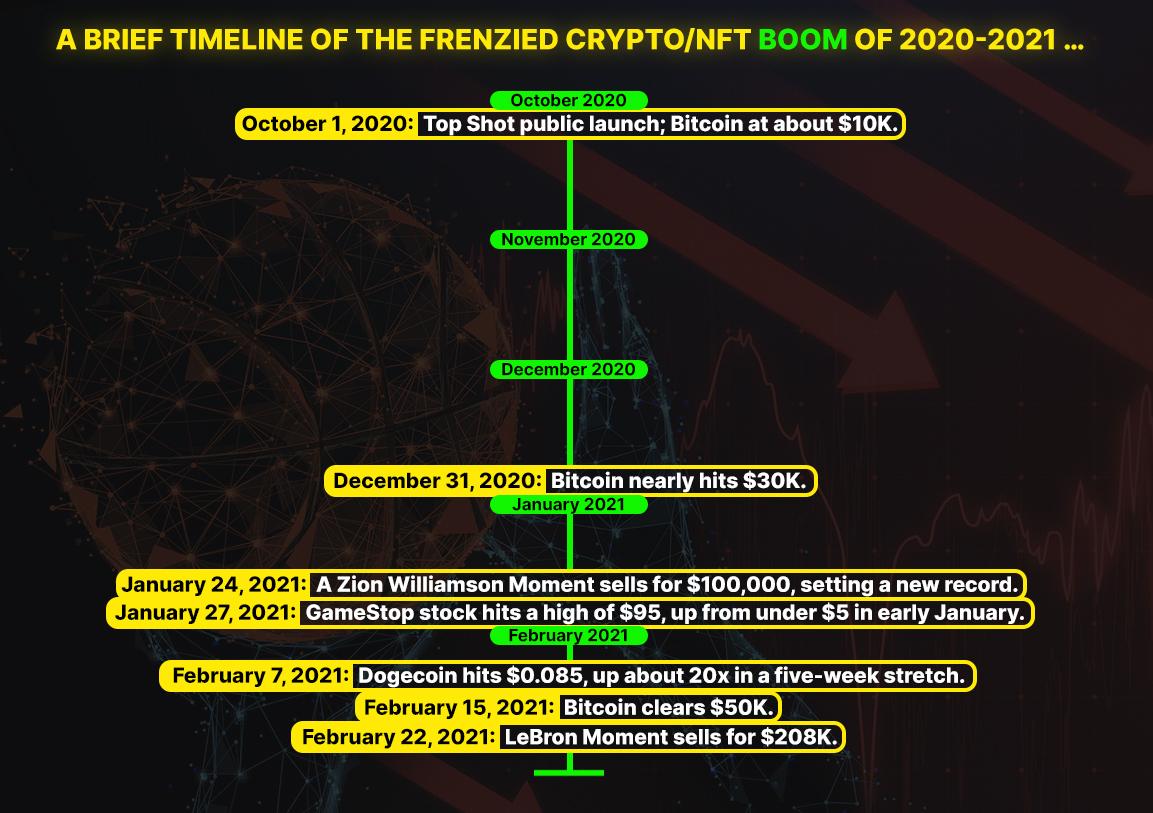

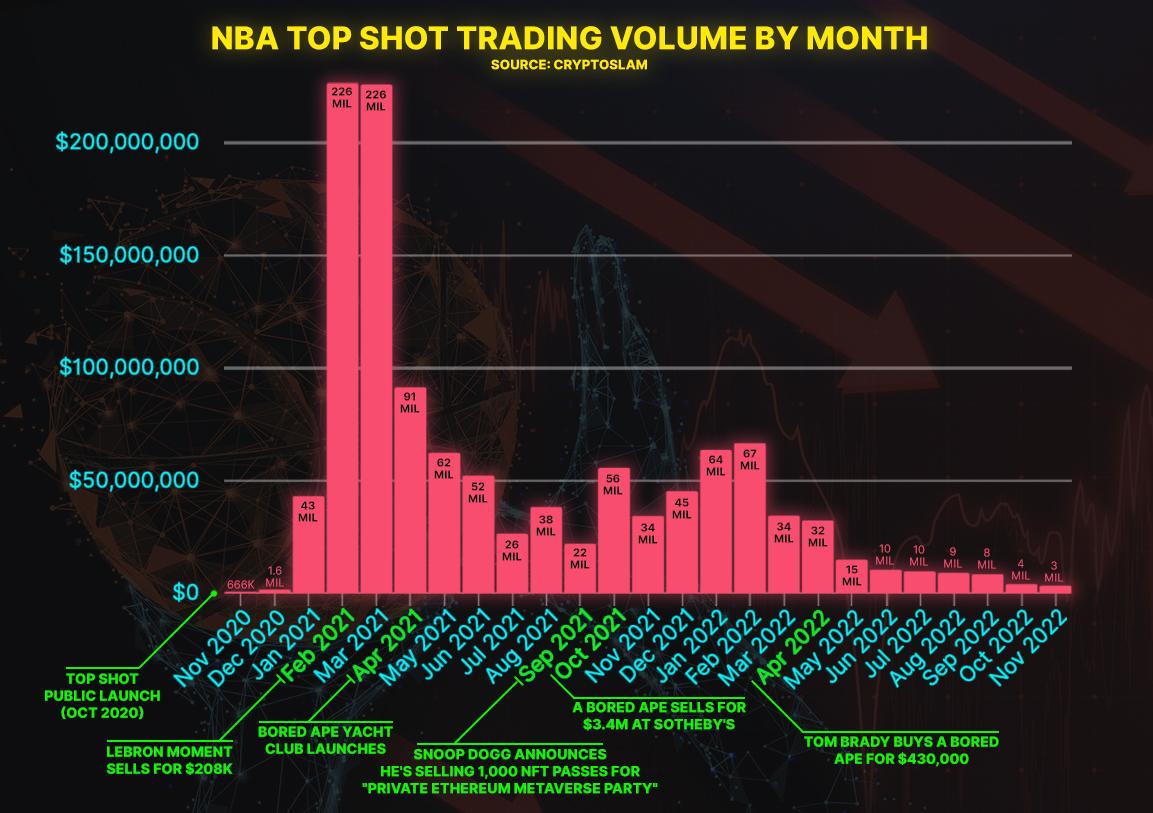

On February 22, 2021, this clip sold for $208,000 on NBA Top Shot, the league’s delirious NFT venture. It marked the high sale on a record day during which $47.88 million worth of similar video clips, called “Moments,” were traded on the platform. A video of James Wiseman finishing an uncontested dunk, of which Top Shot minted thousands of digital copies, sold for $13,666. A clip of Ben Simmons sold for $20,000, one of Goran Dragic topped it at $30,000, two Zion Williamson Moments sold for six figures.

As prices climbed, crypto insiders, pandemic-weary hoops fans, and NBA players themselves joined in, buying digital packs, trading Moments, and pushing the numbers ever higher. Devotees were certain that this was a new frontier—that paying $13,678 for a clip of Kentavious Caldwell-Pope finishing a runner in the lane represented a fleeting chance to get in on the ground floor. Skeptics saw a house of cards, not the future of them.

Somehow, both groups were right.

Top Shot did popularize digital collecting through NFTs, or non-fungible tokens. They were a fringe mystery when Top Shot launched, but Moments broke into the mainstream, introducing many to Web3 and paving the way for a surreal industry boom. Within a month of Top Shot’s explosion, a digital art piece by Beeple sold for $69.3 million. Soon after, NFT projects like CryptoPunks and the Bored Ape Yacht Club reached unbelievable heights, filling doubters with existential dread. But unbeknownst to the company, Top Shot’s own golden moment had come and gone by then. The $208,000 LeBron Moment trade proved to be the priciest sale on the busiest day in the platform’s history—the absolute peak.

Then Top Shot’s bubble burst in spectacular fashion. In a flash, prices began to fall, and the company found itself ensnared in workplace drama and entangled in a legal battle with distressed users. Meanwhile, savvy crypto traders rolled out in search of the next big thing, leaving Top Shot and its user base twisting in the wind.

From its manic high to its steep fall, Top Shot’s arc seems like a classic boom-bust tale in an era with so many of them.

But then its story is not so neatly canned. Its rise provoked larger questions about the sketchy state of sports fandom, the tussle between sentimentality and progress, and the reasons we value the things that we do. And its fall, well—it’s complicated. Four years on, Top Shot is still here, still fighting to reclaim its good name and cultural standing.

“We wanted to be a sustainable part of the fabric of the league,” says Roham Gharegozlou, the founder and CEO of Dapper Labs, which created Top Shot. “I think a hundred percent we can be and will be.”

But even if Top Shot can engineer itself for the future, it may always be best known for its past.

As early as 2017, when Bitcoin was worth 2 or 3 percent of its present value and the words bored, ape, and yacht could not exist in the same sentence, the NBA was exploring potential blockchain projects. The league likes to experiment often, from Finals shirseys to LED courts, and harbors dreams of international expansion.

It found a kindred spirit in Dapper Labs. The company’s brain trust had already created CryptoKitties, which was among the first collectible NFT games (perhaps the first, though it’s disputed). There, users buy, sell, and breed (“breed”) googly-eyed cartoon cat tokens. Next, Dapper Labs had an idea for an NBA platform. It would be engaging, novel, built on technology that was “completely theoretical as far as I understood,” says Caty Tedman, the company’s former head of partnerships. Tedman helped pitch the idea to the league, but “it was a complete Hail Mary,” she says.

All the better for the intrepid NBA. “After our first meeting, I knew right away that we’d do a deal with them,” says Adrienne O’Keeffe, the NBA’s head of digital products.

Top Shot is a live wire. Its app seductively blends everything, basically—TikTok and Robinhood, SportsCenter and blackjack. It moves at the speed of today’s impulsive sports fan. Moments, those signature clips, can be traded 24/7 on Top Shot’s secondary market. They’re also available in packs, which typically run $9 for nine “Common” highlights, $24 for a guaranteed “Rare,” $230 for a guaranteed “Legendary,” and up to $1,499 for special-edition releases. As the user opens a pack, hype music plays while highlights spring to life in a neon cube. The platform runs on the blockchain, which allows for certain perks unique to NFTs. Two stand out: that users can view real-time data on resale values and supply, and that Dapper Labs, NBA players, and the league itself earn royalties indefinitely by sharing a 5 percent cut of each trade. (This includes trades on “approved third-party marketplaces,” according to Dapper Labs.)

On the surface, Top Shot seems like an absurd distortion of memorabilia. In theory, collectibles tie us to sports history and to our own history by being actual things that actually exist. But the industry has been shifting away from romanticism and even tangibility for decades. Collectibles are now a commodified investment class driven by textbook economic forces. The market is still churning, but its low end is all nostalgic clutter, its high end all paperwork and fractionalized shares of things like Ty Cobb’s bat. It is still underpinned by a sentimental charm—and the fact that the stuff exists. But the spirit is dimming, and it’s fair to wonder whether holding a trading card in one’s hand will mean much to a fully digital generation. Top Shot represents an aggressive, polarizing leap forward—or into the abyss, depending on your perspective. To the common objection that the product makes no sense, Top Shot asks: “As kids get older, are they going to want to collect cards and put them in shoe boxes, or will they want to flaunt them on social media?” says Jacob Eisenberg, an early Top Shot hire and its current chief of staff. “Are they going to want to bring them around in their pocket, or on their app?”

As kids get older, are they going to want to collect cards and put them in shoe boxes, or will they want to flaunt them on social media? Are they going to want to bring them around in their pocket, or on their app?—Jacob Eisenberg, Top Shot chief of staff

In June 2020, NBA Top Shot launched as a closed beta, accessible by invite only. By then, the COVID-19 pandemic was in full force, halting countless normal things, including the basketball season. Sports fans in quarantine grew desperate for action—video game simulations became gambling fodder, marble races went viral. Yet Top Shot’s early action was modest. “When I first got on Top Shot, the idea of buying a digital collectible was insane, even for $20,” says Jesse Schwarz, who signed up that August—and would later lead a group of buyers on the $208,000 James Moment purchase.

Count me among the disbelievers. While researching this story, I discovered that Top Shot had offered me access via email in October 2020, when the public was first invited. But like many others, I had no interest in stepping out on that limb. The platform drew just north of 2,000 unique buyers that first October, according to data from tracking platform CryptoSlam!, and only about half that the next month.

Then strange things began to happen—and many of those things played into the hands of Dapper Labs. First, crypto got moving. Bitcoin had been trading at under $10,000 when Top Shot launched; by late December 2020, it had nearly tripled, bringing lesser-known coins along for the ride. Just before Christmas, the NBA season began—an anomaly caused by the pandemic. Meanwhile, a second round of federal stimulus checks were sent out across America, and somebody who went by DeepFuckingValue was gaining steam on Reddit with a theory about the explosive upside of GameStop stock. On January 15, 2021, a respected voice among gamblers and daily fantasy players, Jonathan Bales, announced he’d spent $35,000 on a Ja Morant Moment. On February 6, the trading volume of Dogecoin—created “as a joke” by two software engineers and cosigned by Elon Musk—exceeded 14 billion. The following month, FTX, a cryptocurrency exchange, bought the naming rights to the Miami Heat’s arena.

Rolling the dice in this environment looked like good business and good fun. Millennials in particular (I’m 31) jumped at the chance to try our luck. We were about twice as likely to invest in crypto products as Gen X, and five times more likely than boomers. That’s partly because we’re generally poorer than our parents, and many of us have been priced out of home buying. For some of us, trading volatile assets represented a way to strike back against growing economic inequities—and a chance to keep pace. But this wasn’t a social movement. Speculating provided an antidote to the daily stagnation brought on by the pandemic, a link to others across social media, a window into futuristic tech, a platform for pure sarcasm, an ironic bit backed by nothing deeper than a desire to ride the hot hand. All told, says Russell Belk, a professor at the Schulich School of Business and a renowned authority on collecting and consumer behavior, “Millennials and younger people have been cut out of a lot of things and they want to strike it rich.” For this generation, he adds, “the volatility is sort of the attraction.”

Top Shot blended the enticing volatility of a dynamic market with the nostalgic pull of trading cards. Moments felt tailor-made to meet the moment. “When the product went viral, it was at a very unique time in human history,” says Gharegozlou.

In Top Shot’s earliest months, new packs might languish on the digital shelves for days before being purchased. By January 2021, says O’Keeffe at the NBA, “there was a pack drop and I went in after a couple hours and it was gone. The site was down, things had crashed. I was like, Oh no. From there it was an absolute rocket ship and chaos—in the best possible way.”

Soon, even doubters could hardly resist hopping aboard and ripping a pack. On February 21, a friend of mine texted, “What’s the point? People buy this stuff for $200k? I hate this.” On February 25, he said, “We’re getting in. There’s a pack drop at 12.” By then, I was either convinced of the product’s legitimacy or overwhelmed by FOMO; in the heat of the moment, it didn’t really matter.

But as I tried to get in, I got bounced at the door—Top Shot had started to shoo people away, routing them to a waitlist, lest they overwhelm the system.

For those with a coveted account, pack drops became a titillating affair. Hundreds of thousands of people entered lotteries just for the chance to buy a pack. And how sweet it was to be chosen.

“You open a pack and get this huge rush and—ahh,” says Ernest Filart, a physical therapist in Redondo Beach, California. Filart warmly recalls buying a LaMelo Ball Moment for some $700 and watching it spike to $10,000 within a weekend. “Picking up these virtual Moments—it’s not real, you can’t touch it, but it made you feel so good. I couldn’t sleep. I was running on pure dopamine.”

Picking up these virtual Moments—it’s not real, you can’t touch it, but it made you feel so good. I couldn’t sleep. I was running on pure dopamine.—Ernest Filart, Top Shot user

As interest picked up from crypto investors and the general public, Top Shot masterfully kept one foot in the shadowy Web3 world and one in the bright lights of the NBA, where users had their identities verified and mostly paid with credit cards, bypassing the crypto labyrinth. (The league’s legal department was “mega-involved” in the product’s development, Tedman says.)

“I started collecting Top Shot NFTs and I didn’t even realize they were NFTs at the time,” said the rapper Ja Rule, who later sold a $122,000 NFT commemorating the phony Fyre Festival, which he cofounded. “I just thought they were like the new digital sports cards.”

Across Twitter, Reddit, and Discord, ecstatic communities formed, celebrating glorious pulls and talking of endless upside. Stephen A. Smith campaigned to have his jumper memorialized on the Top Shot marketplace. Third-party sites sprang up to help Top Shot users track their holdings in real time. Everyone saw a lot of green.

“You could buy anything and it was going up by multiples in hours,” says an early user named Phil, 43, of Sarasota, Florida. (He requested to have his last name withheld due to privacy concerns.) He says he turned $27 into a peak portfolio value of roughly $16,000. “It was just white hot fire where you could do no wrong.”

At 1:33 a.m. ET on February 23, 2021, Tyrese Haliburton paid $819 for a clip of Nick Collison making a tip shot. Why would he do this? Collison, who had already been retired for three years, was a stiff anti-highlight as a player. The two are not from the same city and don’t share a position. Haliburton attended Iowa State, a Big 12 foe of Collison’s alma mater, Kansas. The purchase defies logic—or rather illustrates the warped logic of a gold rush, to which NBA players themselves gave in.

“This has become an addiction,” Haliburton told HoopsHype at the time. “I’m on the website all day.”

In turn, Haliburton and his peers provided Top Shot with an alluring legitimacy—the notion that this was not an underground gamble but an above-board piece of sports culture. Players signed on and traded Moments, interacted with fans, interacted with each other. On the court, “I heard guys say in games like, ‘Oh, that’s a Top Shot!’” Josh Hart told me in April. Cole Anthony got into collecting through Terrence Ross; Terry Rozier and Damion Lee agreed to swap NFTs instead of jerseys after a game. Others simply followed along in amazement.

“I showed Zion the price of how much people are selling his Moments and a lot of them were putting astronomical numbers there,” Hart said at the time. “He was like, ‘What the fuck?’”

But not all players felt the sticker shock. Harrison Barnes leaned into the craze, likely spending more money on Top Shot than any other player. He collected a pricey Chris Paul Moment ($39,995) and many more—of LeBron ($23,000), Jamal Murray ($21,449), Jayson Tatum ($31,000), and so on. The tracking website LiveToken pegs the cost basis of his current holdings at $412,212. (Players’ usernames are verified through Top Shot, which is a little odd. While the blockchain is supposed to make transactions transparent, identities are meant to be obscured. Haliburton, Barnes, and a number of other players declined to be interviewed for this piece.)

In late March 2021, Barnes beat the Cavs with a game-winning jumper. Haliburton, then his teammate with the Kings, shouted, “Put that on a Top Shot!” The company obliged; Barnes spent $2,400 to buy a pair of them, and Haliburton scooped another for $699.

The NBA itself relished the moment, too. It was an unusually tense time for the league. Ticket sales had evaporated during the pandemic, and amid an ongoing feud with China, the NBA had reportedly missed its revenue goal by $1.5 billion for the ’19-20 season. Top Shot was a much-needed hit. As All-Star Weekend approached in 2021, the NBA announced the Rising Stars rosters on Top Shot (though the game itself was skipped as a COVID precaution). On ESPN, Kendrick Perkins opened a pack live with Hart’s assistance and pulled a Moment that was selling for $8,800.

In March 2021, some five months after the public launch, Michael Jordan came on as a Dapper Labs investor, as did Kevin Durant and many other active players. The company’s valuation would grow to $7.6 billion. While naming it among the Most Innovative Gaming Companies of 2022, Fast Company declared that Dapper Labs was “making Web3 safe for normies.” Mark Cuban (who bought a few Moments) saw the platform as a natural home for new-age investors. “This generation doesn’t care what Old School Wall Street thinks or says about valuations,” he wrote. “All these narratives are just sales pitches designed to sell stocks, and they want to change the game and kick their ass.”

To change the game, all one had to do was spend $37,500 on a Rui Hachimura Legendary Cosmic (and pray that an even bigger ass-kicker would pay more later). Ostensibly, this was a flicker of vision of a new philosophy on finance, adulthood, life, a new (mostly male) American Dream, maybe—to get rich quick, to have a laugh, to watch some hoops, to scroll your phone, to hit the group chat, to roar when it works, to shrug when it doesn’t. It’s a familiar scene now, as we embrace (or tolerate) a gambling-crazed sports industry. But before the siren song of the same-game parlay blared during every commercial break, before common fans grew as interested in rebounding totals as the score itself, before all four major leagues found themselves ensnared in athlete gambling scandals, there was an NBA-backed product in which Lonnie Walker IV clips sold for five figures—and official tweets implored fans to keep spending. Following the infamous sale of that LeBron Moment, Top Shot’s account declared it a triumph. “The top acquisition for any NBA Top Shot Moment ... so far,” it said, the challenge explicit, the delirium radiant. “Congrats on the nice pickup!”

Over at Dapper Labs, the race was on to meet demand. These were still the early, hectic days of a startup. Everybody on staff worked across jobs, and “the pace was a lot to deal with,” says Gharegozlou. In a matter of weeks, Top Shot’s active user base had ballooned from about 2,500 to more than 400,000. The stampede put new pressures on the platform’s infrastructure and in-game economy. The system cracked.

The website (which hosted Top Shot before the company launched its app) often crashed in key moments. As a temporary solution, Dapper Labs reduced the availability of packs, which eased traffic. But that left a growing user base chasing a limited number of Moments, which produced a funny by-product: exclusivity. Insatiable demand. “When you’re talking about collectibles, the whole thing is about scarcity,” Schwarz says.

Meanwhile, another happy accident worked like a force multiplier in the marketplace. As prices climbed and certain users tried to extract their profits, a great number of them discovered they couldn’t. At least not yet. As Dapper Labs installed an identity verification system, the ability to withdraw was granted on a rolling basis. For many users, the wait time was measured in months. Eisenberg recalls that during the 2021 Super Bowl, on February 7, he was pulled away to respond to a “huge problem.” Some 7,000 unresolved support tickets had piled up, and withdrawal delays were “a lot of the source of the tickets.” As of March 26, 2021, only 28,000 users could withdraw funds; hundreds of thousands could not. There were delays as late as October ’21, a year after the public launch.

In the meantime, few users had the patience to sit on their money (which was being held as what the company calls a “Dapper Balance”) and wait for verification approval. “It was so fun and the graph was only going up,” says Eisenberg. “I think both greed and FOMO led to everyone putting that money back in.”

“It was funny money,” says Schwarz. “It was just recycling different Moments into other ones, and all of it was you couldn’t really take the money out. And so I wouldn’t consider it real dollars. The big headline was the $208,000 purchase, but that wasn’t going in [or coming out of] my pocket.”

When I talked to sports collectors during that time, they told me, “Look, I can’t jump in right now because it’s clearly a bubble.”—Roham Gharegozlou, Dapper Labs founder and CEO

Dapper Labs had engineered a flawless inflationary machine: inventory was limited, which helped draw new money to the platform, and old money couldn’t leave. It’s tempting to wonder whether it was all done by design, a grand scheme to jack up prices, manufacture hype, and collect trading fees. But Gharegozlou insists that it was merely a series of honest efforts and unintended consequences. “It’s very easy to Monday morning quarterback and assume we were masterminds at every step of it, but most of the time we built a product and we were trying to hold on for dear life,” he says. Many Top Shot users—myself included—see it the same way.

Still, the offshoot was chaos. A Joe Ingles shovel pass in the lane for $10,425. An Al Horford block for $11,099. A Lu Dort layup for $13,750. Even Gharegozlou acknowledges that the market grew problematically inflated. “When I talked to sports collectors during that time,” he says, “they told me, ‘Look, I can’t jump in right now because it’s clearly a bubble.’”

Indeed, the value of Top Shot Moments in early 2021 was less new world order and more claustrophobic economy fueling itself, an infinite staircase trending up at every turn.

A thing like that can’t go on forever. “You can only sustain with new people coming in,” says a former Dapper Labs employee.

“You Are In,” the email subject line said. “Now Get That Collection Started.”

It was March 9, 2021, and I was finally off the Top Shot waiting list.

Weeks earlier, as my friends became confusingly rich (on paper), I had set my sights on a specific Moment: a Carmelo Anthony bucket that I thought was sure to climb in perpetuity. But as I read the invite email, I felt an odd paranoia. If chumps like me were being let in, I thought, the clock might be ticking—as Phil, the former user, puts it, “You can only buy so many second-edition Bradley Beals before shit hits the fan.”

The day I received my access email, Top Shot did $13.3 million in trading, an astounding number that somehow was down about 80 percent from the peak on February 22. The next day, $8.8M … then $6.8M … $6.1M … $3.9M … $3.3M …

Conversely, the broader NFT market was heating up. Beeple, the digital artist, sold Everydays: The First 5,000 Days on March 11, 2021. The Bored Ape Yacht Club launched its obscenely popular product on April 29. Yet from March to April, Top Shot lost nearly 80,000 unique buyers, some 20 percent of its total. Many of them had flipped their way into a Top Shot fortune and went looking for the next Web3 score. From May to July, as countless other NFT projects climbed, Top Shot shed nearly half its user base again. Prices wobbled accordingly.

Across community social channels, users grew tense. “There were some rough days in the Discord,” says Robert Fink, who worked as a Top Shot community manager. “This is people’s money that you’re talking about here, and a lot of the conversation shifted from the product and talking basketball to, ‘How is Top Shop going to save my bags?’”

Internally, some employees wondered whether Dapper Labs could save itself.

Throughout 2021, during good times and uncertain ones, the company seemed to operate in classic unicorn form, spending lavishly to make noise and look the part. “We were playing in la la land,” says one former Dapper Labs employee. “We just spent, spent, spent.” As NFT.NYC approached in November 2021, for instance, staffers were told to quickly pull together a star-studded party at any expense. Several hundred thousand dollars later, there were Quavo and Ja Rule at the music venue Terminal 5.

“That’s when I should have known,” says a former employee in attendance. “When I saw Ja Rule, I should have said, ‘Let me see if I can get my old job back.’”

That’s when I should have known. When I saw Ja Rule, I should have said, “Let me see if I can get my old job back.”—Former Dapper Labs employee

By then, the stability of the company was in question. More than a dozen former employees from various departments and seniority levels spoke to The Ringer for this story under the condition of anonymity. Collectively, they describe a frantic startup struggling to scale a novel product at lightning speed, hindered by internal drama and strategic missteps.

Some point the finger squarely at Gharegozlou. Always an archetypal tech founder looking to move fast and break things, he seemed to grow only more aggressive and demanding as the Top Shot market cooled. “How he talks to people, what time he talks to people, what he expects of people—he was relentless and he was omnipresent,” says a senior-level source. Some feel that he went too far, creating an environment of “fear and panic and obsessiveness,” according to the former staffer, where impulsive decision-making and chronic staff turnover seemed to stifle the company’s progress.

“He created such a dynamic of rapidness and fear in individuals that he had everyone wrapped around his finger at all times. And he would leverage that,” says another former senior-level employee. “He wants to strike fear in you.”

When told of how some former employees describe his approach, Gharegozlou does not quite shy away. He participated in two video interviews with The Ringer last year, in February and November. “I think the intensity level was appropriate and I think we still are a very intense workplace, and that’s kind of what you need to succeed,” he says.

He adds, “I always take full responsibility over any negative experiences people had at Dapper or on the way out from Dapper. But at the end of the day, I’m focused on doing the right thing for our community, doing the right thing for my shareholders.”

But as Top Shot prices slid and interest waned, the company struggled to execute that mission.

“There was no real plan,” says another senior-level source. “The fact that the investors continued to put in money was a joke. If they only knew what the inside looked like.”

Within Dapper Labs, some staff felt that the pressure to scale prompted hasty decisions. For instance, in May 2021, the company launched Collector Score, a bizarre point system that made 100 Common Moments together more valuable than a single Legendary, akin to 100 dusty cards in an attic outclassing a prized rookie card in mint condition. It went live without warning, according to one senior-level source, abruptly upending the Top Shot game and shocking some employees. When asked about the launch, Gharegozlou says, “I don’t remember that being a surprise, but it is true that a lot of people expect multiple approval cycles and big meetings to get full sign-off. I don’t think that’s how decisions should be made at startups. It’s appropriate to move fast.” A year after its introduction, Collector Score was replaced by Top Shot Score, overhauling the game once again.

In April 2022, a $1 million credit giveaway was green-lit in the middle of the night while most employees slept. (“I don’t remember that specific anecdote,” Gharegozlou says.) Staffers awoke feeling alarmed but not surprised by the news. “That’s what it was every day,” says a former employee. Adds another, “That’s the kind of shit that was happening all the time.”

In general, the company has struggled to maintain a stable marketplace, and some employees wonder not only about the strategy behind the numbers but the morality of the dynamic, as well. “We decided how much the economy was pushed with new inventory,” says a former senior staffer. “We were the [Federal Reserve] and Fort Knox—we decided it all. It’s kinda fucked up.”

Top Shot controls its supply and can pull certain levers to gin up demand. In late 2021, it launched a program called “Flash Challenges,” which offers rewards for collecting Moments based on real in-game stats. On Christmas Day in 2021, for instance, users were tasked with collecting the five leading scorers from the holiday slate. When Nets guard Patty Mills scored 34 points against the Lakers, vaulting him among the day’s leaders, users rushed to purchase his most highly minted Moment (i.e., his cheapest one). It had been selling for around $4. Suddenly, it skyrocketed above $40 and reached a high-water mark of $130.

Originally, Flash Challenges occurred sporadically, as the name implies. But around mid-2022, as Top Shot prices fell, management pushed to run them far more frequently, according to a former employee who worked on them. “They were trying to pump money to the marketplace,” the source says. “The Challenges were definitely a pumping ploy.”

Then again, it can be hard to firmly apply labels within this slippery industry. If Dapper Labs engineers a way for Patty Mills Moments to arbitrarily spike by 30 times in a single night, is that a manipulative ploy or shrewd business? The answer seems to melt away into the infinite gray area that is the NFT marketplace, where new dilemmas constantly are bubbling up.

Try this one: Recently, I noticed a banner on the home screen of the Top Shot app. It advertised a $5 pack called Grail Seeker. The promo said that in each Grail Seeker pack, there’s a 5 percent chance of unearthing a Rare Moment, such as a Cade Cunningham clip that “recently sold” for “$1,495” or a LeBron Moment that “recently sold” for “$1,499.” The implication was that whoever pulled the next one could sell it for nearly $1,500. But it’s not quite the truth. According to public sales data, the only account that had spent close to $1,500 on those Moments in recent months is called NBATopShotBuyback, which is run by Dapper Labs. The company uses it to buy Moments from the marketplace and repackage them in packs. The result is a bit misleading. The last time an actual user had purchased that Cunningham Moment, it was for $1,019, not $1,495. The James Moment had most recently sold to an actual user for $1,000, not $1,499. The user who drew it from a Grail Seeker pack later sold it for $750, or about half as much as the advertisement had suggested.

As with Flash Challenges, the situation raises awkward questions. If Dapper Labs institutes a buyback program that distorts market values, but the buyback purchases are publicly visible, has the company wronged its users? Gharegozlou says, “The insinuation that ‘recently sold’ is manipulating prices and market action in one direction or another is just not true.” Speaking broadly, he adds that, “We don’t engage in market manipulation.” In an email, a Dapper Labs spokesperson adds that the company’s legal team reviews all new offerings “to ensure consumers are provided with all expected and necessary information to make informed decisions.”

In any case, some of the company’s problems have read less like a moral quandary and more like a PR crisis. “At Top Shot, anything that can go wrong will go wrong,” says a former employee.

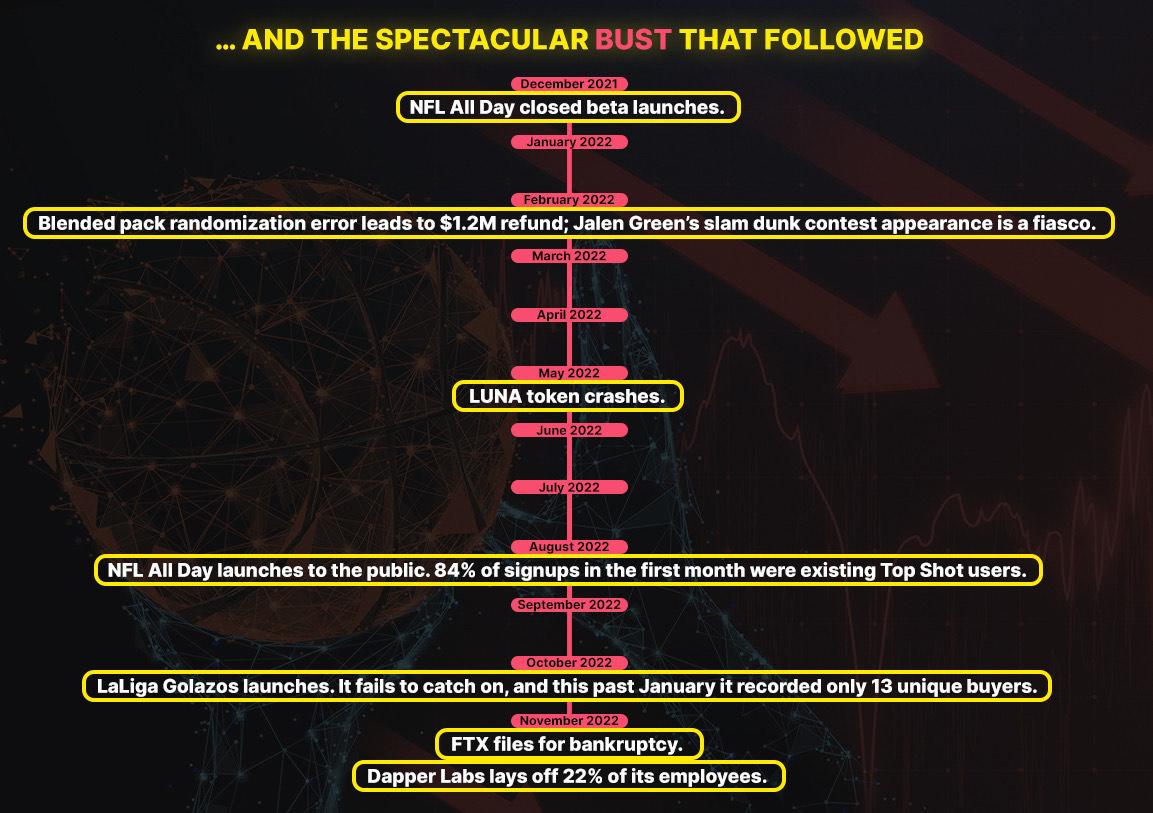

In February 2022, a new partnership campaign with Durant helped drive a nearly 25 percent increase in buyers from the prior month. As users flocked to the platform for a pack drop curated by Durant himself, Dapper Labs decided to unveil a new product: blended packs. For the first time, users could pay a flat rate—$49—for a pack that might contain anything, with a slim chance at drawing a Legendary Moment. Instead, a randomization glitch served up the Legendaries in direct succession to a small number of users, including some who received five in a row. To make good, Top Shot refunded each person who bought a $49 pack, of which 24,868 were available. Its massive Durant campaign produced little more than this ad and a $1.2 million refund.

When asked about this fiasco, a former senior-level employee texted, “Hmm, don’t remember this randomization issue in particular. It happened a lot.”

Two weeks after that debacle, a pricey slam dunk contest campaign with Houston’s Jalen Green went haywire. He fumbled the product placement, a video NFT of himself dunking, which played on an iPhone attached to a gold chain necklace, and struggled for several minutes to land a dunk. In the broadcast booth, Dwyane Wade confused Top Shot for Coinbase. “Nightmare fuel,” says one former employee, not least because Wade had already launched a signature pack with Top Shot (which itself drew backlash as an ill-conceived cash grab).

That same month—February 2022—a CryptoPunk sold for a record $23.7 million. The NFT market was still bullish. Yet within weeks, Top Shot’s unique buyer count fell by nearly half.

Still, Dapper Labs’ most consequential mistake, a number of sources agree, was entering into a problematic licensing contract with the NFL in 2021.

The two sides had been in touch about creating a digital football collectible for years, and conversations grew serious as Top Shot thrived. For Dapper Labs, new IP could unlock a multi-sport empire. For the NFL, which refers to itself as the Shield, faceless and defiant, Dapper Labs offered a gateway into a future driven by stars.

To launch official sports collectibles, Dapper Labs pays to secure licensing rights from leagues and their players. The company guarantees its partners a minimum payment, regardless of the product’s performance. Dapper Labs then hopes that number will be covered by royalties from NFT sales. When times were good, royalties more than covered the Top Shot guarantee, pegged by multiple sources at around $8 million to $12 million per year. (The 5 percent Moments trading fee shared by Dapper Labs, NBA players, and the league itself added up to nearly $50 million in 2021, and that doesn’t include revenue from pack sales or other avenues.)

But as Dapper Labs negotiated with the NFL, Top Shot was skyrocketing and competition for licensing rights was coming fast. The founders of Fanatics, for instance, had already created a Top Shot equivalent with MLB through a startup company called Candy Digital. Sorare had launched its signature soccer NFT platform and would later introduce a fantasy NFT product with the NBA. In this overheated environment, “there was very unrealistic proposals being floated around by other companies,” says Gharegozlou. Dapper Labs agreed to what several former employees consider a catastrophic contract with the NFL and OneTeam Partners, a marketing firm cofounded by the NFL Players Association.

“The NFL waited,” says a former senior-level employee who viewed the contract terms. “That’s the difference between the NBA and the NFL. The NBA is innovative, NBA is first. The NFL waited, and when it was time, they crushed us.”

In exchange for pro football licensing rights, sources say, Dapper Labs guaranteed annual payments in excess of $40 million. (According to one source, this could potentially be paid through some blend of cash, tokens, equity, and more; the NFL and NFLPA reportedly took a stake in Dapper Labs as part of the deal. “The specifics are highly confidential,” says Gharegozlou. He acknowledges that he negotiated the NFL deal, but adds, “I think we did good deals and we built real partnerships.”)

To deliver on its guarantee, Dapper Labs would need its new football product to be nearly as successful as Top Shot had been in 2021, year after year.

In December 2021, Dapper Labs launched NFL All Day as a closed beta. Quickly, its operators noticed a problem lurking in the data: 84 percent of All Day signups in the first month were Top Shot users, according to Dapper Labs. The company wasn’t attracting new dollars. “We were just taking money from one product and moving it to another,” says one former senior-level employee. “That’s when I knew we were kind of fucked.”

Across all of 2023, All Day’s first full year, only $18.8 million was traded on the market. (Top Shot’s first full year: $923 million.) At the outset of a multiyear contract, Dapper Labs fell well short of recouping its guaranteed fee, and eventually terms had to be renegotiated. (According to RT Watson of The Block, OneTeam Partners threatened Dapper Labs with a lawsuit, but it’s not clear whether this was in regard to the guarantees. No legal paperwork was ever filed.)

As trouble mounted, Dapper Labs compounded one critical mistake with another: flooding the Top Shot marketplace with new Moments. When Top Shot peaked in February 2021, there were about 13 new Moments for each buyer. By November 2023, it was 63-to-1.

The increased supply met an already-thinning demand, which sent Top Shot prices lower, which thinned demand further, and so on. Across 2023, 2024, and into this year, Top Shot activity plunged. Two sister projects launched by Dapper Labs in 2022, UFC Strike and LaLiga Golazos, failed to catch on. In January, Golazos recorded only 13 unique buyers.

To be sure, powers beyond Dapper Labs’ control quickened this downturn. If Top Shot had caught fire due to perfect conditions, All Day experienced just the opposite. Its public launch, in August 2022, occurred at precisely the wrong time. Many of the most popular NFT projects were backsliding dramatically. A so-called stablecoin, Terra’s LUNA token, had crashed a few months earlier, wiping out $40 billion, and the FTX disaster would soon rock public faith in crypto. (The FTX name was stripped from the Heat’s arena in January 2023.) The market for traditional collectibles had also calmed after an electric stretch during which there were a number of record-high sales.

They caught lightning in a bottle, and didn’t know what the fuck to do with it.—A former Dapper Labs employee

That the high-wire frenzy of 2021 proved unsustainable for Top Shot and unreplicable for All Day is not itself a failure or a surprise. A market where Jonas Valanciunas blocks fetch $13,755 should probably cool off; a Mac Jones pass, minted to 10,000, now carries a sensible $1 price tag. But if a brutal market correction was inevitable all along, and if Dapper Labs’ rollicking success depended on shaky external forces—all that only underscores the danger of contracts that “don’t make provisions for downturns,” as Tedman says, necessitating an endless peak.

“The cardinal sin in the deals was really the upfront guarantees,” says a former employee with knowledge of the terms. “To me, that was the sad part about it.”

Dapper Labs, like many NFT companies, cut its staff as prices tanked. It laid off 22 percent of its 600-plus employees in November 2022, 20 percent in February 2023, 12 percent in July 2023, and still more in 2024.

“They caught lightning in a bottle,” says one former employee, “and didn’t know what the fuck to do with it.”

There used to be a page on Top Shot’s website where you could see which NBA players owned Moments, called Certified Ballers. According to the Wayback Machine, it was pulled down in October 2022, right around the NFT bust. Well, as the market soured, players fared no better than common Top Shot users. For the $412,212 Barnes invested into his current holdings, LiveToken estimated a value of around $25,000 as of Monday, February 24—an unrealized loss of about $387,000, down 94 percent. Haliburton is down over $56,000, or 89 percent. He hasn’t purchased a Moment since 2022.

In the age of athlete-as-entrepreneur and athlete-as-PR-maestro and athlete-as-everything, this marks a rare high-visibility slip. It’s more notable in the wake of the FTX scandal, which resulted in the likes of Steph Curry and Shaquille O’Neal having been named in class action litigation for promoting a fraudulent product. Top Shot is a legitimate product, to be sure—but athletes did earn more in royalties and partnership money as its bubble inflated. Some even profited by trading with fans. Hart was once gifted a Moment by a fan and quickly sold it for $2,500. Haliburton was gifted a Moment and listed it on the marketplace for $20,000. Forty-six seconds later, the user who had just gifted it bought it back for $20,000 and never sold it. (Afterward, the user tweeted an “investment thesis” positing that owning a Moment once held by Haliburton could someday be akin to owning his digital autograph.) It’s a curious modern dynamic—one players are not keen to explore.

Many NBA players declined or did not respond to interview requests for this story. Klay Thompson invested in Dapper Labs and collaborated on a custom Top Shot pack. I asked the Warriors whether he might want to discuss Top Shot (before he left for the Mavs). The team checked in, but it seemed like Thompson “did not have much interest in Top Shot.” I reached out for an interview with Spencer Dinwiddie, the league’s most vocal crypto backer. He also invested in Dapper Labs (and once told me that he bought and sold Bitcoin during practice). But Dinwiddie declined to chat about Top Shot, too. I asked the Heat whether Terry Rozier or Tyler Herro might be more inclined, given Rozier tweeted excitedly about Top Shot and Herro voiced a video explainer. A team representative said, “I spoke with both guys, and unfortunately, they were not into the Top Shot stuff.”

Some players who boosted Top Shot may have been more interested in the perks than the technology; Dapper Labs paid “stupid” money to players for content partnerships, according to one source. For some players, “they were getting a bag—they didn’t care,” says another former employee involved in athlete partnerships. “We’d literally be on set and they’d be like, What am I here for? What is this? What’s an NFT?”

Well, fair enough. I, like many, did not come to Top Shot to collect ’em all or revel in the supposed wonder of Web3. I too was caught up in the moment, enticed by a cut of the action and the chance to say I was there when striking it rich required just a little cell service and hoops insight. If I was speaking the same language as day-trading athletes, it was not that of connectivity or futurism but self-interest. In Top Shot’s heyday, a lucky user could buy a pack for as little as $9 and be certain that its contents were worth more. This was arbitrage, not basketball culture.

In that sense, Top Shot completed collectibles’ larger evolution from hand-me-down keepsakes to bloodless commodities. Trading cards first arrived in the back half of the 19th century, but the modern story is some 45 years in the making, tracing at least to 1979. That’s when the Beckett Price Guide arrived, offering a common reference point for a secondary trading card market that had existed mainly in disparate corners, from garage sales to motel road shows. The market boomed throughout the ’80s; by 1990, it was frothy enough for a major league umpire to walk out of a Target with thousands of stolen cards stuffed down his pants, intending to “collect and trade.” (He was suspended and then retired after he was sentenced to three years of probation.) The boom spawned a comical number of card companies, and they produced a comical number of cards, perhaps 80 billion per year. They overshot the market, much as Top Shot later would. From ’91 to ’95, sales plummeted by nearly half.

Then eBay arrived, sparking new demand from online buyers. Leagues grew stingier with licenses, limiting supply. Prices rose throughout the 2000s. In the 2010s, YouTube and Twitch streamers popularized case breaks that hunt for elite cards, and more platforms began offering fractionalized shares of high-end memorabilia held in a vault somewhere. Briefly, these concepts seemed to stretch the connection between new-age collecting and the old-school ideal as far as it could go. A card was still a card, tethering us, however loosely, to our youth, to our idols, to a shred of sentimentality amid the math.

Then Top Shot arrived, pulling it further still. The product provokes an existential question: What does it mean to own a digital collectible? The dilemma looms over all NFT platforms, of course, but perhaps especially this one. You can find CryptoPunks absurd, but they are original creations whose ownership guidelines are clear. On Top Shot, users don’t actually buy the rights to clips, which are NBA property (and don’t feature broadcast audio because of licensing challenges). Moments aren’t art “in any way,” says Christiane Paul, the curator of digital art at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and have “no inherent or intrinsic value,” according to Top Shot’s own terms of use, where the point is repeated four times. The NBA “didn’t want it to become a speculative product for our fans by any means,” says O’Keeffe. What is it, then?

Gharegozlou once offered that Top Shot is, “the currency of fandom for all,” giving it a democratic shape and purpose. But it’s a dubious notion. Fandom is an escape from the daily confines of logic and status. Top Shot’s Leaderboard, on the other hand, celebrates users who “flex their fandom” by shelling out on the platform, implying that the bigger fan is the richer one. It’s completely backward—and calls to mind some immortal words from Durant: “Who the fuck wants to look at graphs while having a hoop convo?”

The question of what a Moment actually is has proved so vexing that it was taken to the U.S. courts in search of clarity—and perhaps regulation. In a 2021 class action lawsuit, the plaintiffs—former users—alleged that Top Shot Moments were not collectibles but unregistered securities (more stock than trading card) and that Dapper Labs had openly invited shortsighted speculation, particularly on social media.

Dapper Labs initially filed to dismiss the complaint, but was denied by United States District Judge Victor Marrero. “The ‘rocket ship’ emoji, ‘stock chart’ emoji, and ‘money bags’ emoji objectively mean one thing: a financial return on investment,” he wrote in reference to Top Shot’s tweets.

Like Top Shot itself, the case broke new ground in the digital space. It is the first instance of plaintiffs sufficiently pleading that NFTs could be found to be a security, according to Paul Lesko, the so-called Hobby Lawyer. (“It’s also one of the few cases that relied on emojis,” he adds.)

But the suit will not provide much closure. In April, it was settled for $4 million, meaning there will be no definitive legal ruling on Moments. (Gharegozlou declared the settlement “Great news!”)

In the meantime, the NFT industry is keeping a close eye on cases involving Dapper Labs’ peers. On March 9, 2023, a class action lawsuit was brought against DraftKings, alleging that its Reignmakers NFT product violated federal securities law. The complaint makes repeated reference to Dapper Labs. On July 2, DraftKings’ motion to dismiss the complaint was denied. On July 30, DraftKings shut down Reignmakers, citing “recent legal developments.”

I definitely understood that someone was gonna get left holding the bag, and I didn’t want it to be me.—Phil, former Top Shot user

The Dapper Labs settlement money (which “seems low,” says Lesko) will first pay off substantial legal fees and then be distributed among tens of thousands of eligible members who bought a Moment between June 2020 and December 2021. It may not warm their hearts. Some users who arrived to Top Shot too late or stayed too long will always harbor a strong resentment for the platform. Consider that over the past year, the top post on Top Shot’s once-vibrant subreddit is titled, “Top shot lawsuit.” For many, says Eisenberg, the chief of staff, “Top Shot doesn’t only have a faint memory in their head, but also kind of an anti-brand of like, ‘Fuck them, I lost money with them, that was stupid of me. Why would I buy more? Why would I spend my money on this?’ And I think that’s really hard to overcome.”

But then, not all users who rode the Top Shot roller coaster feel queasy now, or even robbed of a good time. Most users I spoke with embraced the terms of engagement up front: The product was an unprecedented mystery, Dapper Labs set the pace, and hopefully prices would stay high.

“What did you expect?” says Phil, the former user in Sarasota, Florida. “At the end of the day, if you’re dropping tens of thousands of dollars on digital basketball whatever they’re called, it’s a risk.”

For many Top Shot users, a legal battle is unnecessarily involved, a notion like a currency of fandom for all unnecessarily lofty. On their behalf, Phil puts forth a simpler slogan:

“I definitely understood that someone was gonna get left holding the bag, and I didn’t want it to be me.”

So there it is, that five second video of LeBron James dunking. Schwarz still owns it, some four years later. He does not think of it often. Nor is he tempted to check its resale value. “I haven’t looked in a while,” he says. “It’s pretty down-bad.” With some hesitation, he opens the Top Shot app on his phone, goes into his collection, and scrolls to see the James Moment for which his group once paid $208,000. Its top active offer is $16,000.

Whether this strikes you as absurdly high for a publicly viewable clip of an unmemorable jam or enticingly low for something once worth at least 13 times that probably reveals a lot about your take on all this.

Schwarz, who now hosts a financial podcast, is holding firm. Firm-ish. “I still have that belief in the NBA brand and digital collectibles, and maybe one day another company buys this or they take a different direction or it bounces back,” he says. “Now it’s more in the longer term—maybe in 10 years, who knows?”

In the meantime, Gharegozlou is striving to create sustainable success—real growth through real collectors. “Let’s bring in more of the right kinds of people to grow the product,” he says. “Not sort of chase the crypto people.”

He adds, “We’ve made mistakes in the past, but there’s something really special here and we’re committed to it. We’re not going anywhere. I’m not going anywhere, as much as some people might want me to.”

The notion of Top Shot as a wholesome platform is undercut by gimmicks like TopShotBuyback, which reduce Moments and packs to speculative commodities. But the company has made strides to create a more meaningful product. Fans can unlock Moments by attending NBA games, and money from each trade is being set aside for community development and in-person events. Most promising, perhaps, is a newer feature, “Fast Break.” It’s a clever take on daily fantasy sports, allowing users to plug their Moments into nightly competitions—at long last, an option beyond buying, selling, and staring at them.

Last March, 8,446 buyers spent $5.4 million on Top Shot’s secondary market, the busiest month since 2022. (Viewed another way, these represent 99.98 percent declines from peak figures.) In April, Top Shot auctioned a one-of-one Victor Wembanyama Moment, the first of its kind, for $145,000. It marked the first six-figure sale since 2021. Packs are still selling out. WNBA Moments are now available on the Top Shot marketplace. In October, a clip of Caitlin Clark recording a triple-double sold for $14,500, according to Dapper Labs. (The trade occurred on a third-party platform.)

Then November came. The United States elected a president who shills his own NFTs. He tapped Musk to co-lead the controversial Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE. Since then, the crypto, NFT, meme, and collectible markets are surging like it’s 2021. Dogecoin more than doubled. Bitcoin kissed $100,000 for the first time. CryptoPunks and Bored Apes are rallying. GameStop—yes—has climbed about 50 percent, then fallen, spiked, and so on. Society once again seems eager to spend ironically, speculatively, boldly. And once again, Dapper Labs is on the scene. Gharegozlou has been lobbying Congress to introduce a bill protecting against “future overreach to define all Web3 products as securities,” according to a Dapper Labs spokesperson, who notes that the bill’s chances have “gone up significantly due to the election results.”

Perhaps the stage is set for a Top Shot renaissance. This time around, Dapper Labs boasts not only a tested infrastructure but also tested users—long gone are the fair-weather traders. Consider one Andrew Seo, a graduate student in Chicago. “I’m still a big blockchain believer and I think fundamentally Top Shot is a good product—it’s a pioneer,” Seo says. As prices rose in early ’21, he held most of his Moments, waiting for prices to tumble so the game could begin in earnest. “Now the platform is way better than it was back then,” he says, “but people don’t know that.”

True, many assume that Top Shot disappeared as prices fell, that its story is nothing more than a rise, a fall, and a black screen.

I got hold of a former user named Brandon Leib, 35, who works in sports marketing in Miami. He, like many, remembers the Top Shot glory days with glee. But as we chat, he’s surprised to learn that the platform is still running. I ask whether he still has the app on his phone. He does. Could he log in?

On the other side of the line, I hear him tap around, mumbling as he punches in a one-time code—having long since forgotten his password. “Oh yo I think I’m in!” he says. He hasn’t seen Top Shot in at least three years. “My collection! I don’t believe this. I got a Stephon Marbury, which is kinda fire, a Steve Francis, a Daniel Gafford—wow, he’s good now—a Damian Lillard, but out of 34,000, oh my God, I got a KD!” He clicks to see a few measly pending offers for the Durant Moment, only to learn that in 2021, the same one (albeit with a superior serial number) sold for $7,000. “I’m sick. I could use that money. I’m sick as a dog. Now I’m looking at my best card, a rare Jayson Tatum. What was my Tatum worth? I don’t wanna know; I might pass out. I have a Ben Simmons—that didn’t age well. A Willie Cauley-Stein—for Christ’s sake. Anything else? Let me see.” He scrolls and scrolls, thinking happily of salad days, of the electric group chats, the ecstasy of pack-ripping, the elusive satisfaction of being in the right place at the right time: NBA Top Shot, February 2021.

Or is it 2031 that he’s seeing? “This is honestly—how good is this?” Leib says, and here comes a funny old feeling whistling through. “You know what’s so good about this?” he asks. “Now I wanna buy another pack.” He scrolls on. “I got a Dwight Howard, P.J. Washington out of 9,000, that’s a good one, Jamal Murray out of 14,000. My Lillard could be worth something. And how about my Daniel Gafford? That could be interesting.”