The NBA Is Desperately Missing a Voice Like Bill Russell’s

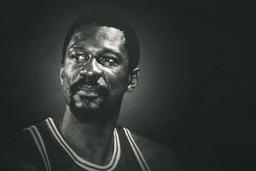

While history repeats itself in this country, modern NBA stars have stayed silent. Maybe it’s unfair to ask so much of athletes, but it wasn’t too much for the greatest champion in NBA history, who doubled as one of America’s greatest leaders.About one month after Medgar Evers was assassinated while walking up his own driveway in Jackson, Mississippi, Bill Russell received a phone call that terrified him. On the other line was the slain civil rights activist’s older brother Charles: “When Medgar was shot you told me you’d do anything you could to help,” he said. “I can use some help right now. But you may get killed.”

Charles Evers wanted Russell to fly down south, host an integrated basketball clinic, and splash a dollop of unity onto a city that was boiling with racism and violence. This was the summer of 1963, in a hotbed of fury and defiance. Russell was 29 and had just won his third straight MVP award while playing for the NBA’s Boston Celtics. He did not want to go to Mississippi and knew there would be tremendous exposure if he did. His wife and friends asked him to turn down the invitation, but their pleas and his fears ultimately weren’t enough to keep him home. “A man must do what he thinks is right,” he wrote a couple years later in his first memoir, Go Up for Glory. “I called Eastern Airlines and ordered my ticket.”

Initially published in 1965, Russell wrote Go Up for Glory with Bill McSweeny in just three days. It discloses the pain and pride he experienced as a Black man in America, frustrated by the slow gears of progress, at times spiteful of his own teammates and coaches for their approach—or lack thereof—to a country in crisis. The memoir’s profundity also speaks to the current moment. It’s as timeless as it is compelling as it is revelatory. “There can be no neutrals in the battle for human rights,” Russell writes. “If you are for the status quo, then you are against the rights of man, because you are afraid to rock the boat. Baby I rocked the boat.”

Reading this today, it’s fair to conclude that 2025 could use someone like Russell, a towering, courageous athlete who’s willing, if not eager, to address a faction of America that is destabilizing and demolishing the protections for marginalized communities that were disturbingly brittle to begin with. He’s honest about his confusion, bitterness, and humility—cerebral and sharp as a knife, all while knowing his own (and every man’s) intellectual limitations.

At the same time that he was basketball’s most accomplished and respected star, the 11-time NBA champion was also unbothered in the face of criticism, bigotry, and death threats—a blunt, unignorable voice that’s now painfully absent from popular discourse. For all Russell fought for up to and after the publication of his first book, Go Up for Glory is a reminder of the response that modern-day NBA players have to ongoing injustices in the United States, which is … almost nothing. It’s trite to compare past and present in this context. The world is much different now than it was over half a century ago. But nefarious ideals don’t magically turn good with the passage of time. They adapt to the age they’re in and then unfurl in their own malicious way.

In a nation that’s aggressively retreating from the progress Russell literally risked his life for, today’s NBA players should not be absolved for their civic paralysis in the face of a presidential administration that aims to resurrect societal mores unseen since Jim Crow laws were deemed unconstitutional.

Their near-collective reticence highlights a pitiful vacuum evident to anyone who watches the second episode of Celtics City—which explores, among other topics, the upsetting relationship that Boston’s Black citizens had with their town—and can’t help but connect prevalent forms of racial discrimination with the same endemic that Russell chose to confront over and over and over again. I first saw the documentary last month. Its grainy talk-show footage of a 31-year-old Russell explaining why he decided to write Go Up for Glory soon had me clicking through eBay to buy a vintage print. The paperback that arrived a few days later was small enough to fit in my pocket. As I read, the glue that held its pages together started to wear off. At a touch, entire sections tore from the binding. And yet, as an artifact of idealism, Russell’s thoughts were more prescient than I expected, a reminder that aspects of today’s plight are no less toxic than they were 60 years ago.

Over the last few weeks, diversity, equity, and inclusion programs and initiatives have been stamped out across corporate America and throughout the federal government. Public education has been directed to be more “patriotic.” Paranoia is en vogue. Dread runs through public officials who kneel in a show of capitulation, hoping threats of intolerance don’t evolve into something even more harmful. At best, this is a regressive movement designed to attack people of color as unworthy and incapable. At worst, it’s the front door of neo-segregationism.

As oppositional strategists and elected officials have seemingly accepted their fate with no clear strategy to combat ethical wrongdoings on a daily basis, it’s a lot to ask NBA players to wade into a divisive, all-consuming fight that requires more time and energy than most people could or should muster on a full-time basis. Juxtaposing Russell’s transgressive approach with today’s choice to tone down pretty much all racial rhetoric is not a criticism of active NBA players so much as a plain observation. There’s a large gap between assuming that much responsibility and spending all this time with their heads in the sand.

Just a few years ago, players seized the moment with voices that cut through a media landscape far more complicated and fractious than it had used to be, knowing financial might and a rare ability to attract attention was on their side. The months leading up to the bubble, and then everything that happened inside, felt like a watershed moment. It’s easy to be cynical about the cultural backlash that’s happened since, let alone the conflicting effort to play basketball during a pandemic while an uprising occurred in the streets. But even though the political climate (and our country’s genuine appetite for tolerance and empathy) is nowhere near what it was in 2020, NBA players still responded to social issues. At the time, I covered the willingness of players like Damian Lillard, Donovan Mitchell, and Jaylen Brown to protest police brutality; the Milwaukee Bucks–led strike after a police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin, shot Jacob Blake; and the creation of a Social Justice Coalition that, well intentions aside, now sits on a back burner with no promotional flame lighting it from below.

Five years ago, LeBron James harnessed his immense popularity and influence to form More Than a Vote, a nonprofit that helped turn basketball arenas into early voting sites and register new voters. Today, James is silent, a development foreshadowed by his mostly idle stance leading up to the 2024 election. His focus instead is on basketball, an expansive corporate portfolio, and the hope of one day owning an NBA team. That’s all his right. He’s done so much communal good over the past two decades that to condemn him outright would be excessive. But just because his drift away from social issues is unsurprising doesn't make it sufficient.

Broadly, NBA players have massive platforms that can reach around the globe. They’re on television. They host podcasts. They have boundless followings on social media, with an audience stretching into the millions. But those forums are rarely used in any capacity to mobilize or inform. Instead, they’re fluffy forms of entertainment, which makes plenty of sense. In these terms, that level of fame dovetails with endorsement deals and commercial partnerships that disincentivize controversy, which, assumedly, is at least one way to explain the passivity that’s currently on display.

While writing Go Up for Glory, some of Russell’s thoughts on the civil rights movement’s direction were scathing, particularly the front-facing figures who backed away when times grew tough. “Many of the Negro leaders who had compromised for years and compelled the status quo suddenly found it very fashionable to be speakers. They were around for a long time. But in the bad days of the struggle, they would say ‘Oh, I’m not involved.’ … The status seekers. But not the fighters,” Russell wrote. “It is not enough to go along, to try to do the gentlemanly thing. Far better to accept the disputes of the world, the harassments, the arguments, the tensions, the slanders, the violence. Raise the question. Confront the blameless ones. We are all to blame. We all must be confronted.”

Activism is not for everyone. It’s taxing, thankless work. But it’s also essential; responses to injustice are necessary as part of an ongoing, centuries-old fight. They do no good if restricted to moments that are popular with no financial or social risk. Nobody wants to lose, but defeat comes with the territory. Racism is an inexorable disease. That doesn’t mean it should be acknowledged, let alone fought, only when victory and applause are the likely short-term result.

In today’s NBA, very few stars are interested in getting their hands dirty. Most players are either unprepared, unprincipled, uninformed, or uninterested in issues involving human rights. Maybe it’s unfair to ask more of athletes, but in the shadow of Russell’s legacy, it’s also disappointing that we have to. Russell was more closely acquainted with cruelty than any NBA player born in or after the 1980s can relate to, and over 60 years later, it’s too convenient to look at his actions and assume they were inevitable.

Russell, who died in 2022, was a controversial figure for most of his life. His views and opinions grew with maturity and acquired knowledge, but many were not popular among the general public. In Go Up for Glory he expands upon some of the more incendiary positions that were revealed in Sports Illustrated two years prior. “I said: ‘I don’t like most white people because they are white. Conversely, I like most Negroes because they are black. Show me the lowest most downtrodden Negro and I will say to you that man is my brother.’ It didn’t sit well. Sit well? Boy, they were ready to hang me. But I said it. And I lived with it. I have never gone back on it to this day.”

There are parallels from that society to the one we live in now. Traces of the same hatred, oppression, and prejudice. And while the average NBA player isn’t regularly forced to hear the type of racist taunts Russell endured during a typical game, those slurs are still deployed—in person and whenever they scroll through their phones. There is no panacea, nor any anti-inequity movement worth latching onto. That doesn’t make it impossible to speak out, but proves how complicated the situation is.

Before too long, there may be someone in the NBA who stands up to the various elements of moral wrongdoing across this country, sticks his neck out, and wrestles with them in a substantive way. This is not their job, and maybe it’s naive to believe anyone will. Having faith in change is routinely an exercise in wishful thinking. But Russell’s legacy makes it fair to debate whether or not it’s their responsibility.

“We live at a time of the greatest changes in the history of mankind. It has been a fierce time and a time of fierce loves and hates and issues. I have fought in every way I know how. I fought because I believed it was right to fight,” he wrote. “No man gains a right to the world who will compromise. It is not a matter for violence. It is a matter for confrontation. It is a matter of asking the question. And some day, it will work. Because men who ask have always succeeded … or been followed by men who have succeeded.”

Russell asked. He succeeded. But right now too few, if any, who wear similar shoes are willing to follow. With no sign of change anytime soon, the fecklessness that exists instead can be seen as its own kind of tragedy.

For more, watch Celtics City, streaming on HBO Max. The second episode is available now.