In the summer of 1979, as he ended one of the most important meetings in basketball history, NBA commissioner Larry O’Brien quipped, “I think that I shall never see a thing more lovely than a three.” The NBA’s board of governors had just voted 15-7 to approve a new 3-point line, a massive jump-shooting subsidy that would change the sport forever.

For nearly a century, through basketball’s explosion in popularity, all field goals had been worth two points. Suddenly, so-called “home run shots” from 24 feet were worth three. Fans loved the new wrinkle. On October 12, 1979, as Larry Bird made his NBA debut for the Boston Celtics, his teammate Chris Ford made the first 3-point field goal in NBA history.

Forty-five-plus years later, on the same patch of Massachusetts land, the Celtics missed 43 of a staggering 63 3-point tries in a loss to the Thunder. They made 41 shots total. In one of the most highly anticipated matchups of the entire regular season—and a potential NBA Finals preview—two of the best basketball teams in the world combined to miss 67 3s in 48 minutes of play.

Of the game’s 176 total field goal attempts, 100 were 3s, and 76 were 2s. Are 3s still “lovely” when they make up 57 percent of a game’s shots?

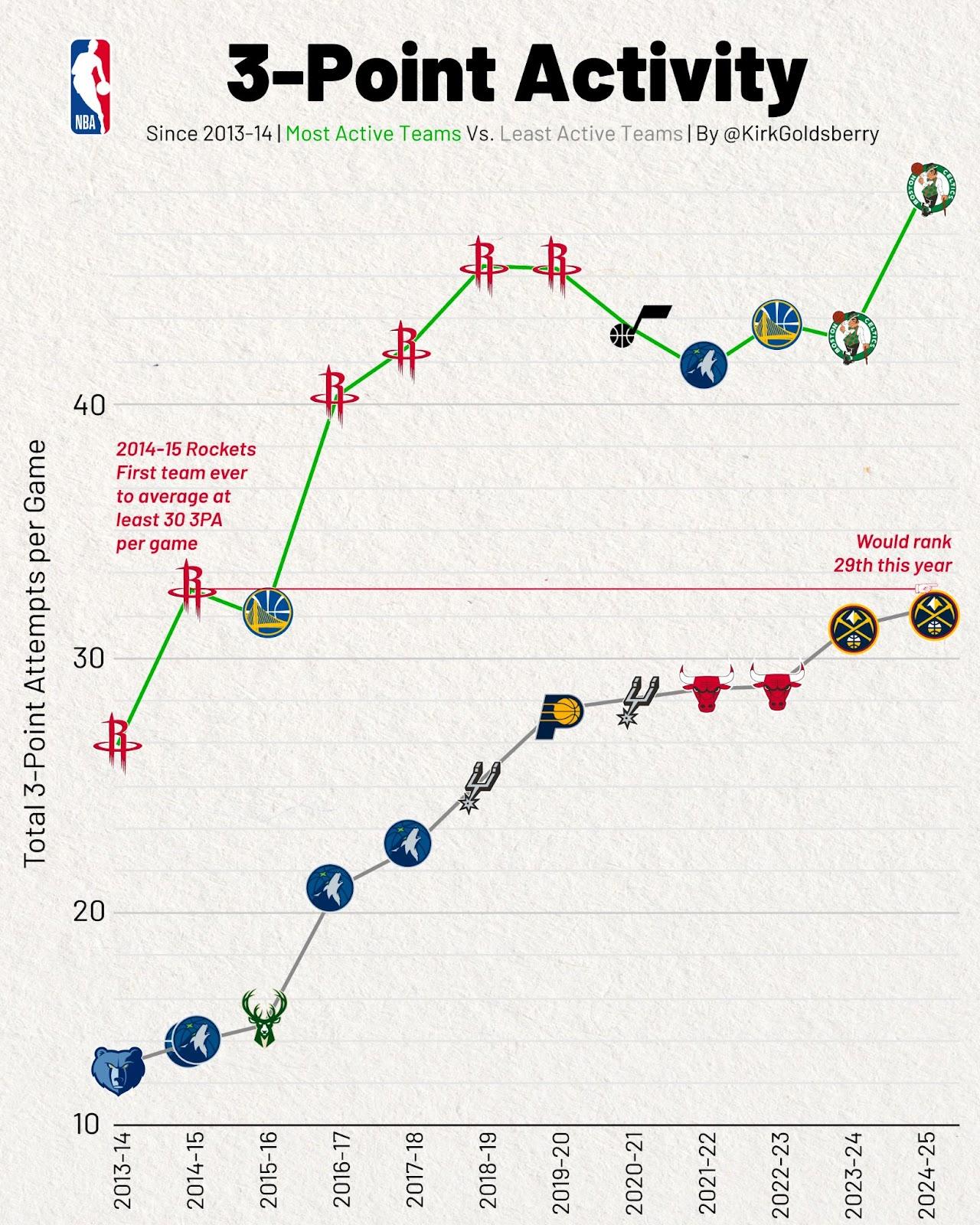

Nearly 50 years after their debut, it’s past time to ask. The NBA’s 3-point arc remains in the exact same place O’Brien and the board of governors drew it in 1979, but the shot itself has gone from novel to routine. As teams have embraced the math behind modern shot selection, the arc has replaced the lane as the dominant tactical landmark on the NBA game board.

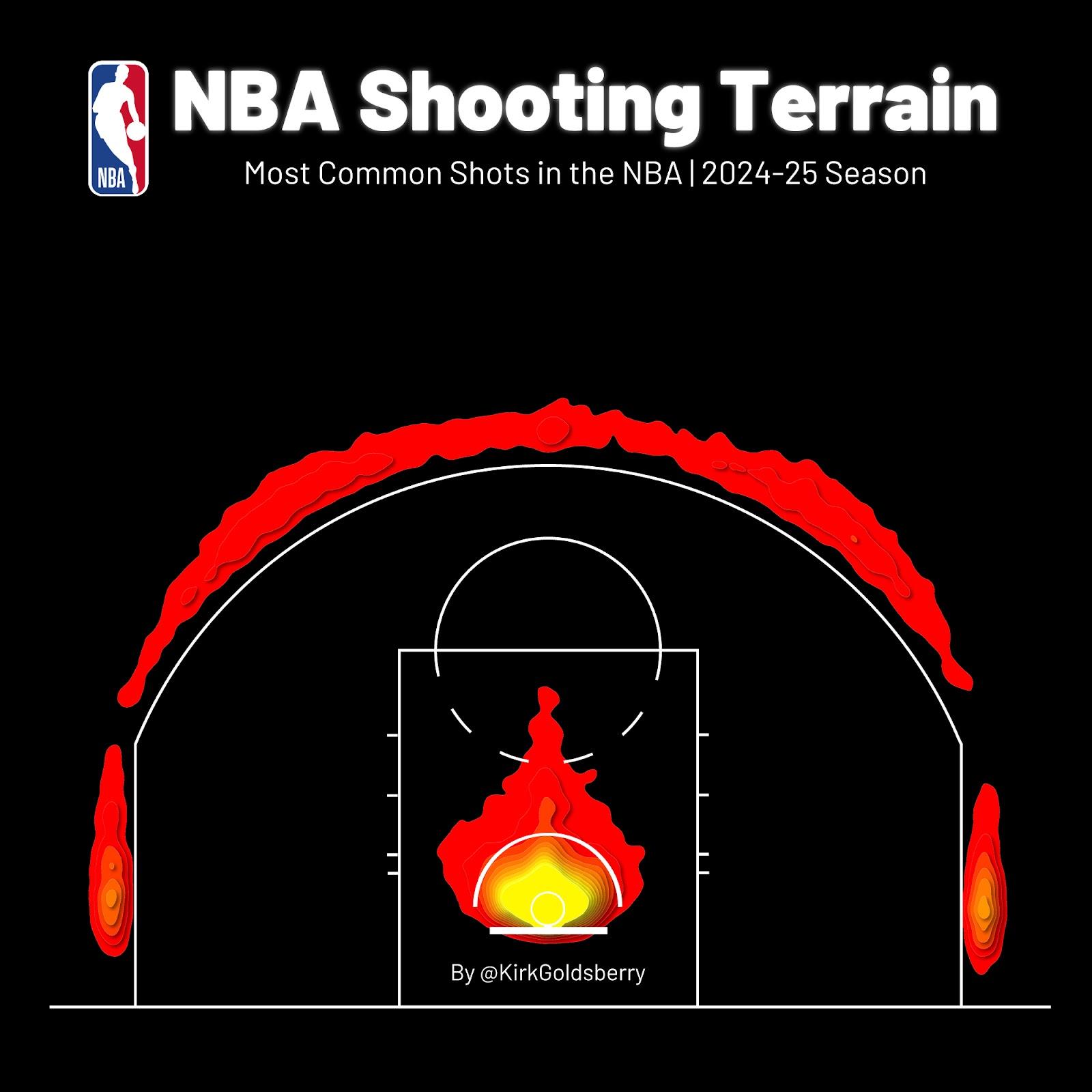

After a brief plateau, the league’s fervor for the 3-ball has surged again in 2024-25. An average 48-minute game now includes 75 shots from beyond the arc, up from 70 last season—that uptick is one of the biggest year-over-year increases in history. Modern offenses arrange themselves accordingly, in catch-and-shoot zones along the line. On today’s playing surface, the corner 3 is Boardwalk. The midrange jumper is Baltic Avenue.

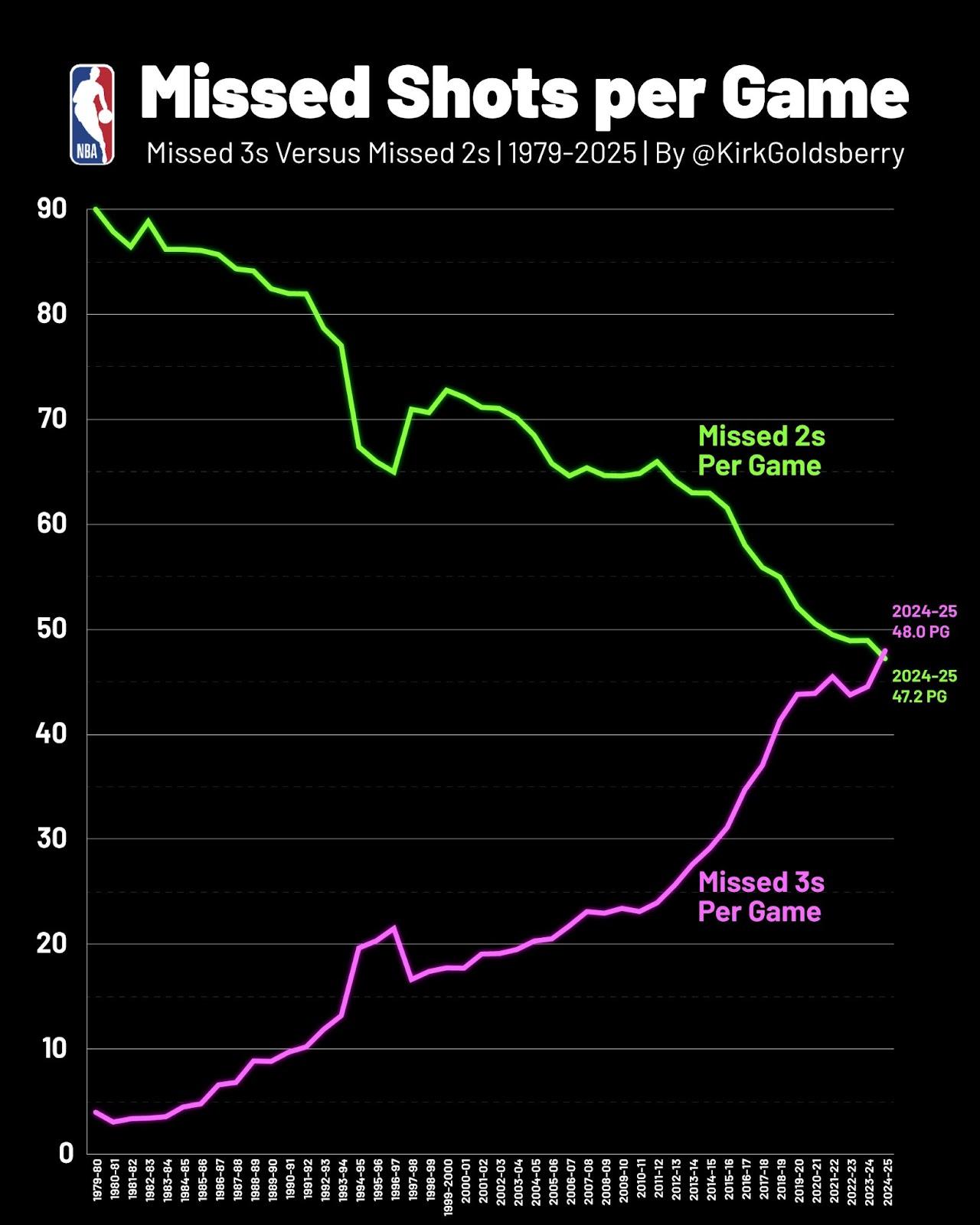

Unfortunately, the arms race to take more 3s doesn’t necessarily mean NBA players are making more of them. Over 64 percent of 3-point shots still fail—that rate has not changed much over time—which means the modern game consists of more and more misses from downtown.

This season, we’ve crossed the Rubicon on a bridge built of bricks. For the very first time, missed 3s are more common than missed 2s.

Welcome to Brick City

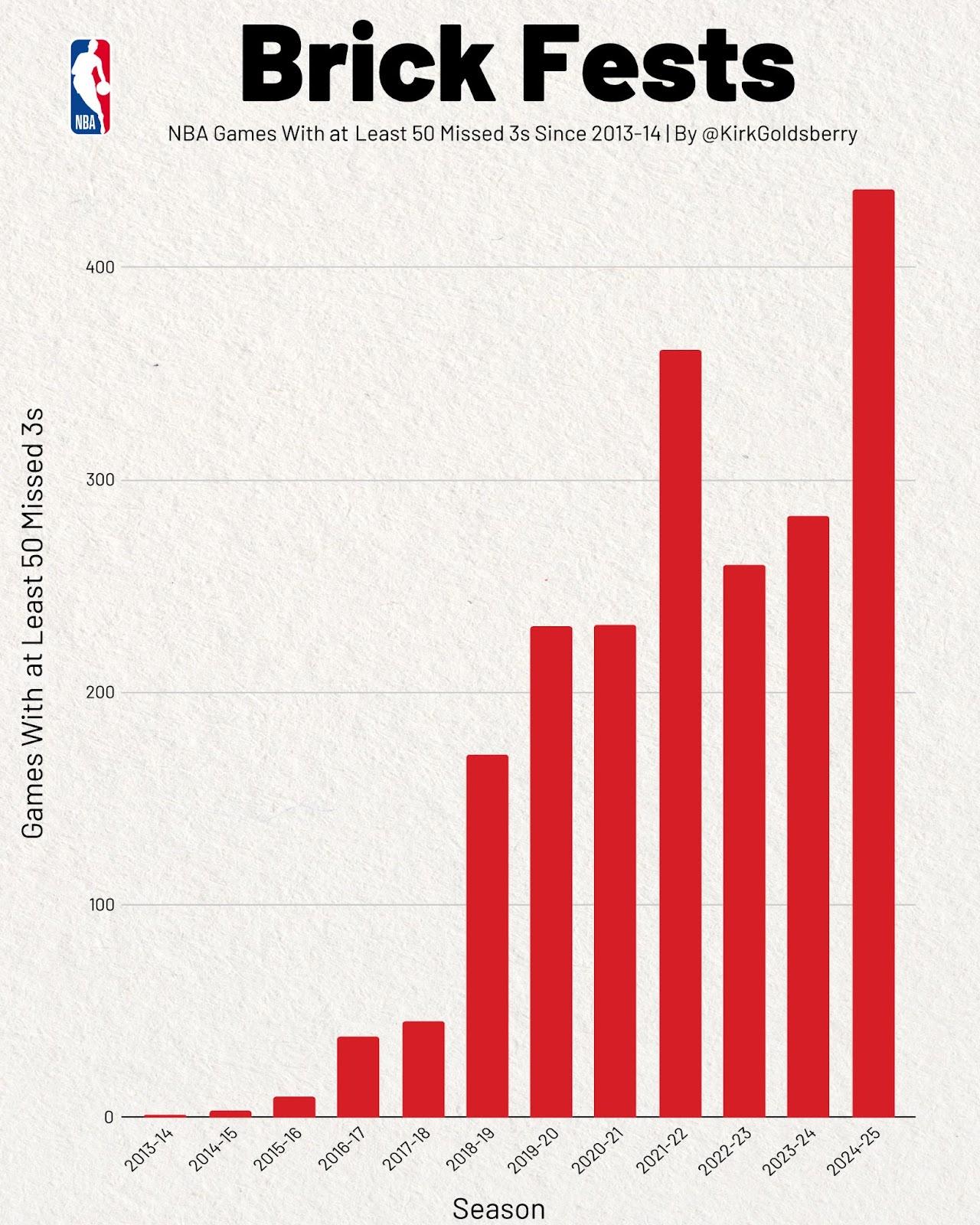

Like it or not, errant 3s are now high-usage NBA superstars. A decade ago, in the 2014-15 season, only three games included more than 50 missed 3-pointers; by last season, that figure was 283. So far this season, an astounding 451 games have checked that box. NBA action now includes exactly one missed 3-point shot per minute of play.

This rise of the 3 has caused a profound transformation in the way pro basketball looks and feels. In dozens of possessions per game, the ball doesn’t even touch the inside of the arc before the offense heaves it from deep. This has had wide-ranging impacts on strategy and technique. For the first time in league history, there are now more 3-point rebounds than 2-point ones; understanding the behavior of bricked 3s is fundamental to rebounding.

The same goes for playmaking and passing. Assist opportunities go to 3-point shooters (58.4 times per game this season) a lot more than 2-point shooters (31.6 times per game). The most important passes in the league used to penetrate the teeth of the defense; now they just orbit the arc as players rapidly search for the next catch-and-shoot opportunity.

The defending champion Celtics epitomize these trends. Back in 2022, in his first season as head coach, Joe Mazzulla laid out his philosophy: “I love 3-pointers. I like math.” The numbers don’t lie. It’s half basketball, half portfolio theory. The Celtics launch 48.5 3s per night, which ranks first in the NBA, puts them on pace to shatter the all-time record, and sets them up to become the first team to shoot more than one 3 per minute of play. As of this writing, Boston has launched 3,636 triples in 3,625 total minutes. In all but 22 of their games this season, at least half of their shots have been 3s.

And it’s working. Boston owns one of the best shooting ensembles in NBA history. An average Celtics 3-pointer this season yields 1.11 points, which dwarfs the efficiency of virtually every other shot type except transition layups and dunks. Shooting tons of 3s is not just a quirky strategy; it’s the right one on a playing surface that promises a cartoonish efficiency stipend for certain jump shots that have become light work for a majority of today’s players.

Mazzulla Ball is a savvy adaptation to the incentives of the 3-point arc. It’s great for the Celtics and the teams that have followed their lead, but it’s a detriment to the NBA product. Missed 3s are the NBA’s junk mail. They arrive in clumps, and no one really wants them. When they were less common, these long-range shots carried novel suspense—a communal breath held between release and result. Now, it’s just another spin of the cylinder. Two bricks and one bucket in three chambers. Seventy-five spins per game.

We should’ve seen it coming. In the biggest game of the 2018 playoffs—Game 7 of the Western Conference finals between Golden State and Houston—the Rockets put on the worst 3-point shooting performance we’d ever seen on a big stage, missing 37 of 44 3s, including the infamous stretch in which they missed 27 straight tries from downtown. These kinds of games are getting more and more common. Boston has missed 37 or more 3s 12 different times this season.

This isn’t a screed against the 3. The shot has given us buzzer-beaters, incredible comebacks, face-melting Stephen Curry moments, Ray Allen in the corner, and the kind of spacing that has helped skilled players thrive. It pulled apart basketball Pangaea and opened up oceans of space for drives, dunks, and high-speed passes. Its impact has spread far beyond the NBA—it’s given us Caitlin Clark and a litany of skilled prospects around the world at every level.

There is no denying that O’Brien’s 3-point shot has been a triumph, but the shot itself is the result of a bold willingness to experiment with new ideas. The fact that the NBA’s 3-point line is still in the exact same place it was back when the board of governors laid it down in 1979 is proof that the league has lost some of its innovative spirit.

Yes, the NBA has added the play-in tournament and the NBA Cup, but in the face of the biggest stylistic metamorphosis in the history of the sport, the league has been slow to address the perimeter monster that has been turning the NBA inside out for over a decade now.

Consider this: Every major basketball league on the planet has moved its 3-point line backward since 2000, except for the one that includes the world’s most talented shooters. O’Brien’s arc is in the wrong place for Adam Silver’s game.

The 46-year-old wrinkle needs a facelift.

A Corner-less Future

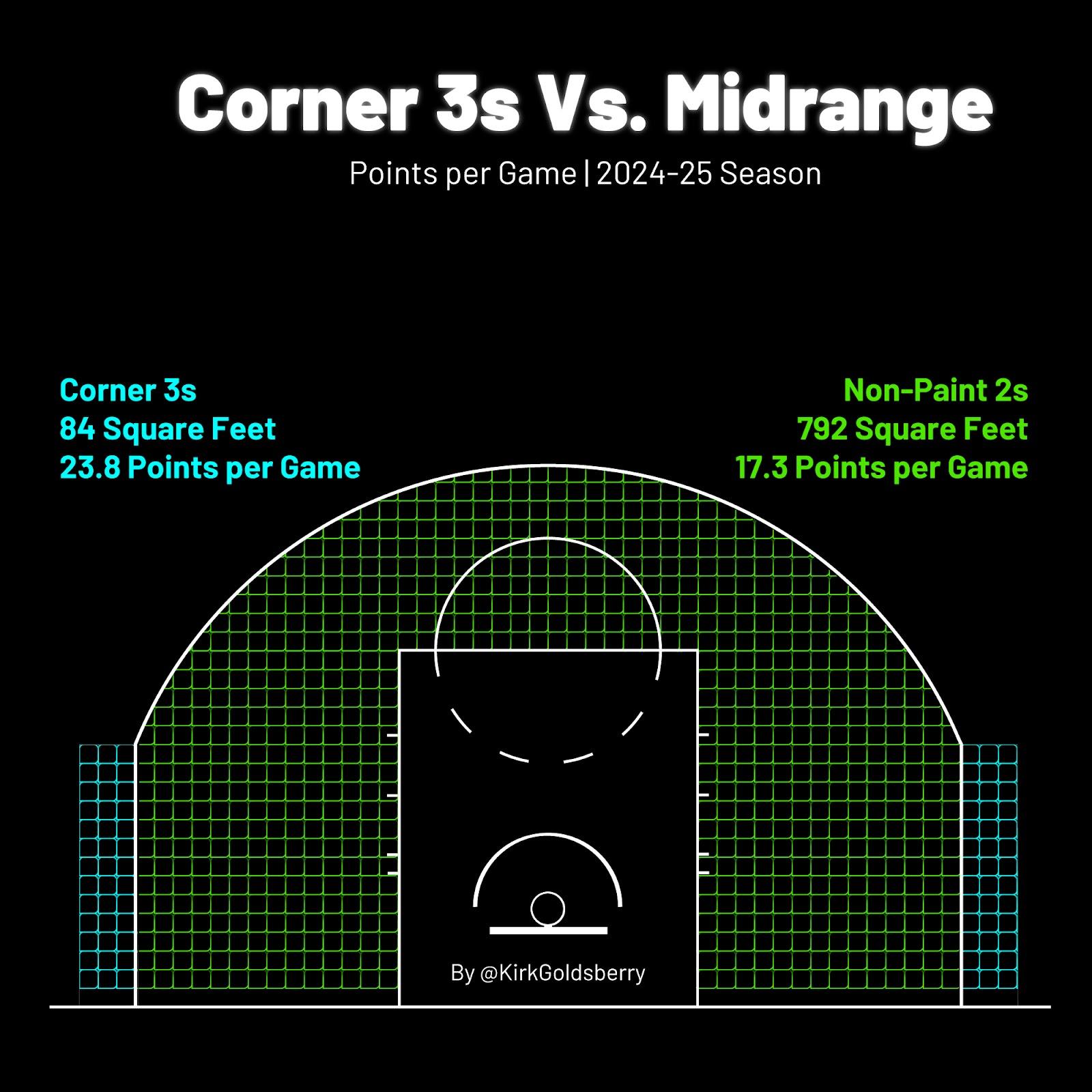

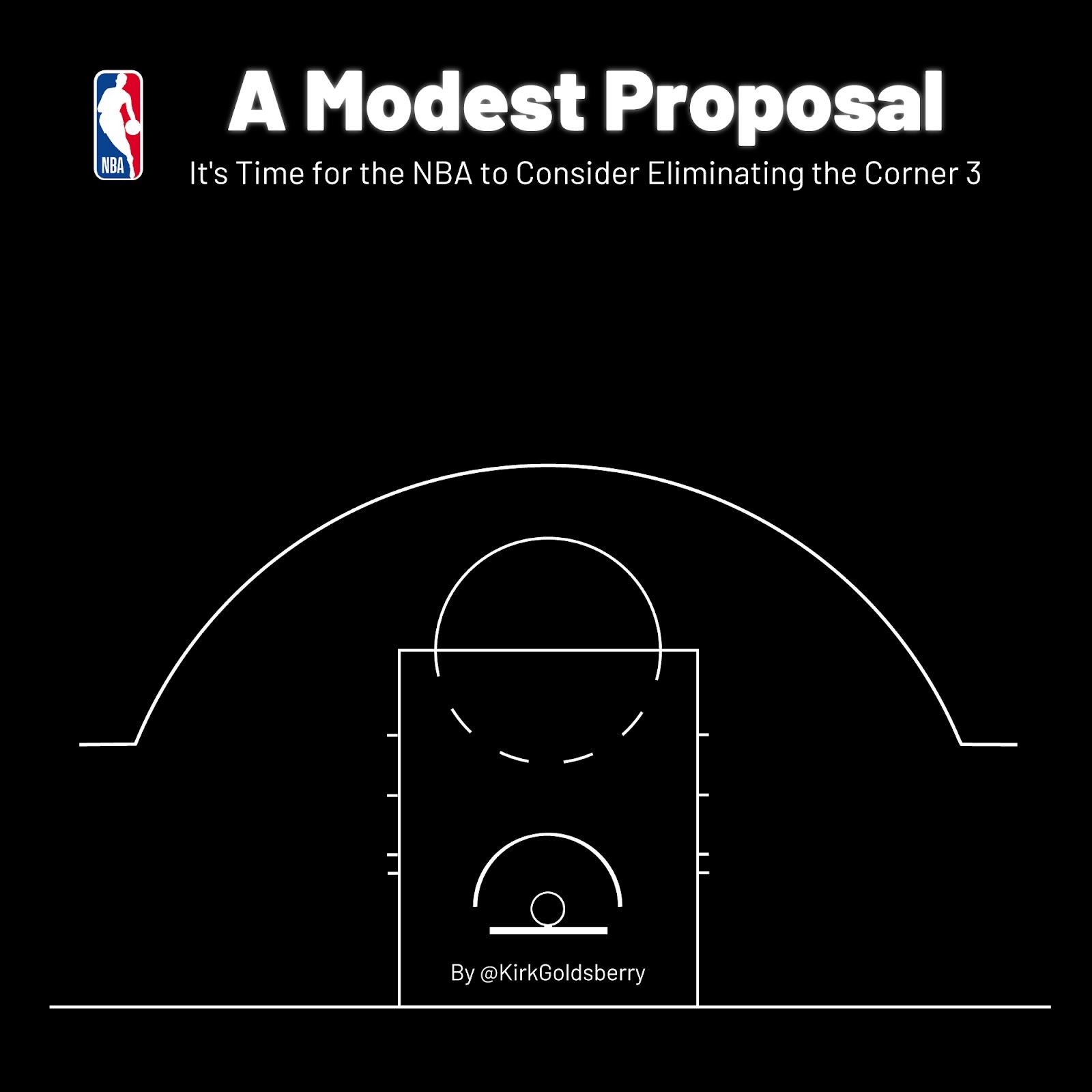

Back in the 1970s, when the league drew the 3-point line for the first time, they put it down 23.75 feet from the rim, but there was one problem: A uniform 23.75-foot arc would not leave enough shooting space in the corners, so they augmented it with two straight 14-foot segments that emerge from the baseline, resulting in shorter 3-point shots from those areas.

That geometric compromise in 1979 made Bruce Bowen, P.J. Tucker, and countless other NBA role players millions of dollars. It also created the most common loitering spot in the modern game. Every trip down the floor, offenses stash one or two shooters in the short corner. Today’s sets are designed in part to create as many of these shots as possible, and now, an unbelievable one in nine shots come from the so-called “short corners.” More points per game now come from the 84 square feet in the corners than from the 792 square feet of space between the paint and the 3-point area.

The corner 3 itself has gone from a role player averaging a few points per game to a star player putting up 24 points per contest. Meanwhile, the midrange—the land of Jordan, Nowitzki, and Kobe—is barren. In 2013-14, an average NBA game included 37 points scored on non-paint 2s; this season, that figure is down to 17.3.

NBA shooters have launched over 84,000 3-point shots this season and made 36 percent of them, yielding 1.08 points on average. But corner 3s, which represent 27.2 percent of all 3-pointers, yield 1.16 points on average. That is more efficient than an average 2-point shot (1.12 points per shot).

That nerdy fact explains why corner 3s are now the most common non-paint shots in the league. But what’s not clear is whether that’s a good thing. Are OG Anunoby corner 3s really “fan-tastic”? Does the league really want these baseline jumpers to be more common than almost every other type of shot?

The best way to inspire more variety on offense is to move the line back and get rid of the short corner.

What would the NBA look like without the army of catch-and-shoot robots parking in the corners every trip down the floor? Let’s find out. Spot-up shooters would have to find other ways to make themselves useful on offense. There would be more demand for alternative skill sets—for post scorers, midrange artists, and savvy cutters. The overall number of 3-point shots would decrease, and a handful of long-range bricks each game would be replaced with something else. And if a deeper 3-point arc screws up the flow of the game, we can always do what David Stern did when he shortened the line during the Jordan era: snap it right back.

We have data that proves today’s shooters would be able to knock down deeper shots. So far this season, NBA players have taken over 47,000 shots from 25 feet and beyond—that’s more total 3s than we saw in any season until 2012-13. Not counting heaves, they’ve made over 35 percent of them.

The corner 3 has become basketball’s version of baseball’s defensive shift. It’s gone from clever to stale. It’s a major efficiency hack that has overstayed its welcome and is threatening the game’s diversity. O’Brien and others created the 3-point shot to open up the game and get away from the monotonous post-up actions that had become tired by the late 1970s.

Well, mission accomplished. Now, an average NBA game includes 75 3-point shots and fewer than nine total post-up plays. The league used to include only a handful of players capable of making these long-range jumpers; now it includes only a handful who can’t. Basketball is at its best when different kinds of players can thrive in different ways. After all, the sport’s five traditional position groups emerged organically over time.

Moving the 3-point line isn’t about going backward; it’s about using the rule book to reverse-engineer the most beautiful basketball in the world. As radical as it may seem, the league office has been doing this for decades. When George Mikan became too dominant, the league turned the key into a lane. When Wilt Chamberlain came along, they made it even wider. When that wasn’t enough, they added a 3-point stripe. Not much has changed since, but the court lines now feel like a souvenir of a bygone era of drop steps and Chuck Taylors; the combination of the super-wide lane designed to reduce post play and the 3-point arc designed for 1970s jump shooters is simply incongruent with today’s game.

The NBA could learn from Major League Baseball. When the strategies of the analytics movement suppressed offense and led to a more static game, MLB brought in Theo Epstein, the former general manager of the Red Sox and Cubs, to apply the same principles he used in the front office to restoring action and diversity on the diamond. His ideas worked. Baseball games got shorter and more action-packed. The nerds will always be on the hunt for the next efficiency hack. Teams will always try to exploit the rules to win games. It’s up to the league to monitor trends and tweak rules in the best interest of the product. This isn’t new; it’s why we have a shot clock, the three-second violation, goaltending, and the restricted area.

The time has come for Adam Silver and Co. to do what Larry O’Brien and David Stern did to build up the best basketball league in the world.

What’s more lovely than a three?

A two.