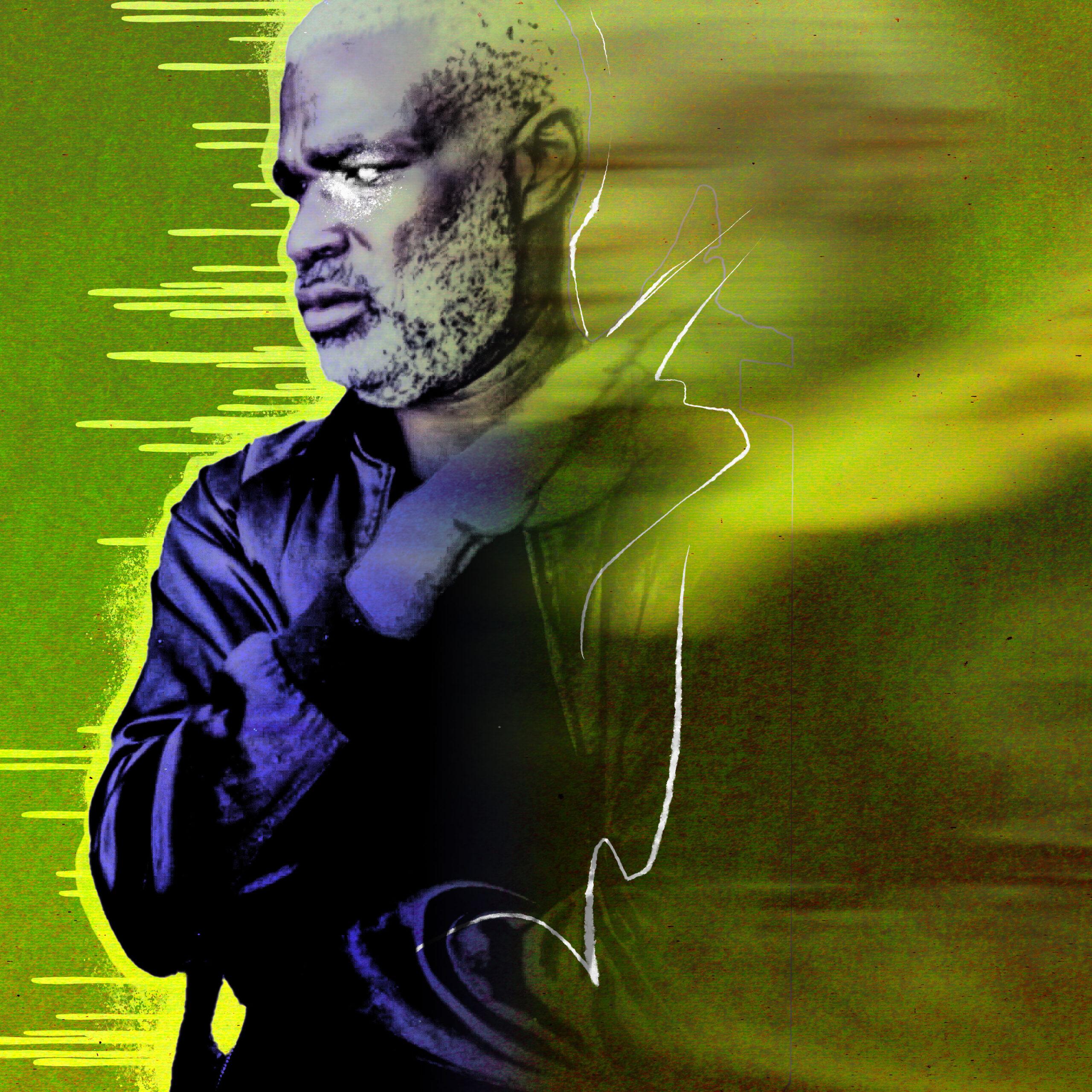

The Reanimation of Tunde Adebimpe

The soul of 2000s New York rock is back with both a solo album and his band TV on the Radio. But he’s not here to save the day, because maybe this day shouldn’t be saved.When Tunde Adebimpe and his bandmates in TV on the Radio began their hiatus in 2019, he fully expected that he might never make music again. And he was completely OK with that.

For over 15 years he’d been caught up in the cycle of recording → touring → recording → touring → recording that perpetuates the lives of rock bands. It had given him little time to pursue acting, directing, animating, making visual art, and all of his other creative interests that are suited to a more stationary lifestyle. A lifestyle that Adebimpe, again, is completely OK with.

What Adebimpe didn’t expect was that a global pandemic would give him time for all these other pursuits, plus enough time to start exploring music again on his own. And what he really didn’t expect was that someone would break into his studio, which in reality is just a corner of his garage where there are some speakers and an interface he can plug into, and steal his shit. Amid the half-finished paintings and boxes of kids’ toys, the thief found a backpack and filled it with a couple of drum machines, a small synth, Adebimpe’s laptop, and 15 years of his hard drives—though not the one that was plugged into his laptop. “They also took my weed, which was the icing on the cake,” Adebimpe says.

What the thief didn’t touch was a box filled with Adebimpe’s old four-track recorder and a decade’s worth of cassettes that went up to 2008, the year he got a Pro Tools setup. As he listened through these tapes, he found some finished demos from the early 2000s that he never did anything with. He also started using the four-track again, feeling liberated by the constraints of not being able to easily erase everything or simply cut and paste his ideas. Making music became fun again.

These old seeds and new dreams eventually led to Thee Black Boltz, Adebimpe’s first solo album, which was released on Sub Pop Records on April 18. It’s a tender and righteous rip through the cosmic doom of this century. At the same time, TV on the Radio has returned for a year of festival appearances, mini tours, and a series of shows with LCD Soundsystem, all nominally in celebration of the 20-ish anniversary of TVOTR’s debut album, Desperate Youth, Blood Thirsty Babes. During a brief run of club dates in New York, Los Angeles, and London late last year, they proved themselves to be just as powerful and necessary as ever. Adebimpe’s also been making an impact beyond music, including acting in memorable roles in the blockbuster Twisters and in the Star Wars extended universe with Disney+’s Skeleton Crew. A quarter century into his career as an artist, Adebimpe now finds himself in his second creative prime.

Sitting in the backyard of a small, nondescript recording studio in Northeast Los Angeles, Adebimpe, 50, still seems surprised by where his life has taken him, all these years later. With white hairs now dominating the stubble on his face and shaved head, he’s self-effacing and charming. He makes it clear that no one expected him to live a life where he’s regularly been the focus of adoring crowds. “A bunch of my old animator friends came to the El Rey shows that we just played [in Los Angeles], and they were just cracking up,” he recalls. “They were just like, ‘It's ridiculous that you're standing in front of that many people and that that's your job, and if anyone had told me that about you specifically when we were working together, I would have said, no, that's not that person.’”

Adebimpe grew up mostly in Pittsburgh, the son of a psychiatrist father, Victor, and pharmacist mother, Folasade, both of whom had immigrated from Nigeria. Like parents of many first-generation children, they expected him to become a doctor, lawyer, or engineer. “If you're not any of those things, you're actually just a derelict,” Adebimpe says. They did come to accept what he decided to do with his life, and Victor later revealed that he also had wanted to pursue an artistic path when he was younger, but entered the medical field so he could send his own sisters to college.

Victor was a major force in Adebimpe’s development. As he would talk on the phone, he would make incredible drawings, which he taught his son how to do. Adebimpe still sees drawing and painting as the grounding of his creative life. Victor also played the piano and had an expansive record collection, filled with King Sunny Ade, lots of classical music, the Beatles, and the Beach Boys—who became Adebimpe’s first exposure to vocal harmonizing, a distinctive element in TVOTR’s multilayered compositions.

Before he died in 2005, Victor saw one of the band’s shows and heard Desperate Youth, Blood Thirsty Babes. “When I listen back to it now, I'm just kind of like, ‘Wow, he really sat through this whole thing? He must have really loved me,’” Adebimpe says. Victor also gave him some advice, telling him that the band should write songs that make people dance—that way they’d make a lot of money. At the time, Adebimpe, still holding on to a punk rock mindset, dismissed him, but in time he realized he was right. TVOTR did go on to make some songs that made people dance. “I guess we made enough money to keep working,” he adds.

But music was just one of his interests when he was younger. In high school, Adebimpe acted and sang in his school’s choir. In the mid-1990s, he attended film school at New York University but hit a wall. “About two years in, I realized that I didn't like telling people what to do, which is a big fail for a director,” he says. He switched to the animation department and soon became enamored of stop-motion. “It's kind of the closest thing to actual magic,” he says. “I like the idea of there's an invisible hand animating all of these things and giving them life.”

After graduation, he put his stop-motion background to use as one of the first animators on MTV’s caustic Celebrity Deathmatch and moved into a primitive converted loft in Williamsburg during the neighborhood's first steps toward gentrification. Among the many people he shared the space with was Dave Sitek, who was primarily painting at the time but would turn into a guitarist and respected producer. The two became friends and started TV on the Radio together, first as an absurdist lark and then as an essential act of the era, anchored by Adebimpe’s soulful voice, which could turn both pleading and demanding. While some young New Yorkers reacted to the terrorist attacks on 9/11 with proto-YOLO abandon, Adebimpe and Sitek hunkered down, afraid about what may greet them outside. They soon added the colossally bearded, falsetto-singing guitarist Kyp Malone to the group and eventually brought on Jaleel Bunton and Gerard Smith—two respected guitarists whom they decided should instead be the rhythm section.

Adebimpe had quit his Celebrity Deathmatch job, and thanks to his friendship with the members of Yeah Yeah Yeahs, he got the gig directing the stop-motion video for “Pin” off the band’s major-label debut, Fever to Tell. The clip was well received, and he was excited to make a go at being a music video director, moving puppets around by himself as he listened to Aphex Twin on his headphones. But then Touch and Go, the famed indie that put out Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ first two EPs, said it wanted to release TVOTR’s EP Young Liars. Adebimpe went with it, thinking the band’s lifespan would last another eight months. It turned into 16 years.

In the press, TVOTR are often called “art rock,” a nebulous description that has been used over the decades to describe bands including Roxy Music, the Talking Heads, and Radiohead. Maybe it was because of Adebimpe’s and Sitek’s visual art backgrounds? Maybe it’s because three of the band’s members wore glasses? Maybe it was because they had flutes in so many of their songs? Adebimpe was never sure what it meant. “I don’t know if it's that maybe you're not good enough to be an actual rocker,” he says. But maybe it’s that in the best cases, the band goes beyond the usual parameters of rock.

The groups that came out of Manhattan and Brooklyn in the early 2000s were often defined by which subgenre or influence from decades ago they wore on their blazers’ sleeves. TV on the Radio’s touchpoints were never easy to define. Across their discography and live performances, there are some hints and direct references—Pixies, Fela Kuti, Eazy-E, David Bowie, Fugazi, Dream Warriors—but they never presented a simple answer. And also, what a goddamn list.

In a predominantly apolitical scene, TV on the Radio was one of the few bands that seemed like it had a message to get across. There were songs about climate change, and following the reelection of George W. Bush and amid the escalating war in Iraq, they released a free MP3 called “Dry Drunk Emperor” that featured the lines “What if all the fathers and the sons / Went marching with their guns / Drawn on Washington / That would seal the deal / Show if it was real / This supposed freedom.” Still, TV on the Radio was also the type of group whose best album, Dear Science, is ostensibly about modern technology’s ability to either save or destroy our world, but it ends with “Lover’s Day,” a nearly six-minute song about life-changing, face-melting sex.

When musician Bartees Strange was still a football-playing high schooler in Oklahoma during the mid-2000s, he was just starting to move away from the hardcore that his friends were into and more toward indie-ish bands like Bloc Party and the National. One day after practice, he saw TVOTR’s performance of “Wolf Like Me” on Late Show With David Letterman and instantly became enamored of them. “I remember actually hearing them and thinking, ‘What are they listening to?’” he says. “Because I know what I’m listening to, and I don’t know how they got there. How do you get there from where we are as a musical society?”

Adebimpe says that when he was a teenager, he was influenced by the DJs with weird time slots on college radio, the eclectic mixtapes his friends would give him, and sample-based music in general. “Just realizing you can take anything from anywhere and sew it together,” he says. “There’s so many permutations of sound and ideas and all of that.”

Adebimpe’s new solo album, Thee Black Boltz, is similarly adventurous and unpredictable. The record is largely a collaboration between him and producer Wilder Zoby. Adebimpe moved to Los Angeles in 2014, when his wife, the cartoonist Domitille Collardey, got an animation job in the city. Zoby is a fellow relocated Brooklynite who has known Adebimpe for decades. They first met amid the borough’s turn-of-the-century music scene (Zoby was formerly in the band Chin Chin and is a longtime musical collaborator of rapper El-P and Run the Jewels), and then their bond deepened because Zoby’s brother was childhood best friends with Bunton of TV on the Radio. “That brought us even more into each other's hemispheres, because Jaleel and I are very much in each other's hemispheres,” Zoby says. Still, the two had never really made music together.

In 2022, Adebimpe was composing the soundtrack to City Island, a PBS Kids show created by Aaron Augenblick, an independent animator whom he knew from the MTV days. The last episodes of City Island’s first season required a heavier musical lift than Adebimpe was used to, so he asked Zoby whether he wanted to help out. “We got into this mode of quick turnover and notes from PBS, who were, if I may say, very harsh taskmasters,” Adebimpe says. “There’s nothing more hardcore than PBS shutting your idea down entirely.”

The pair worked well together, so Adebimpe sent Zoby a few demos, giving him free rein on what direction he thought they should go. “What he sent back to me was not what I would’ve done, but it felt like a very logical but expansive and joyous corollary to it,” Adebimpe says.

They began making Adebimpe’s solo album but then had to take a break for several months to work on a more music-intensive second season of City Island. That pause both indirectly and directly shaped Thee Black Boltz. During that time, they constantly and quickly had to incorporate and iterate on different genres, widening their sonic spectrum. “It fucking dialed Tunde and I in super well as far as communicating and working together and just building trust,” Zoby says. “Trust really is what it’s about at the end of the day, in that this is Tunde’s record that he trusts me to handle. And he did, and he gave me a lot of leeway with this record.”

“I remember actually hearing them and thinking, what are they listening to? Because I know what I’m listening to, and I don’t know how they got there. How do you get there from where we are as a musical society?”Bartees Strange

“Our decision-making, it’s not just two roads to go down,” Adebimpe says. “We’ll allow for precisely 15 roads to go down, and then we’re going to choose the one that works. But we’re going to try all 15.”

You can hear these unexpected pathways in songs like “God Knows,” which comes alive when the country-tinged slide guitar appears, and the “The Most,” a down-tempo breakup recrimination that flips into Adebimpe toasting over the early digital dancehall riddim for “Under Me Sleng Teng.” At one point the duo was tasked with creating a Katy Perry–esque pop song for City Island. When Adebimpe came to Zoby’s studio and heard him messing around with arpeggiated synth ideas, he claimed a chunk for himself and mapped some melancholy lyrics he’d written during the pandemic on top of it, transforming it all into the New Order–esque popper “Somebody New.” The album’s most affecting song may be the electro-acoustic “ILY,” which Adebimpe sings directly to his younger sister Jumoke after her recent and sudden death.

For Strange, who’s now a peer of Adebimpe’s, Tunde’s decision to return to making music speaks to something deeper about him as a person and a creative individual. “It's great when you get artists who, even though they've kind of hit the peak, still feel curious and still want to try things and make things that you wouldn't think that they would make,” he says. “Another artist I was talking about this was literally Beyoncé, when I was talking about Cowboy Carter. You can say whatever you want about that record, but she didn't have to make it. And I think that's one reason why it's so special, because she's still pumped about exploring when she doesn't need to if she didn't want to. She's not doing it for us. I feel like that about Tune, where I'm like, this guy has a robust family life, he has one of the most seminal and important bands ever, and he chooses to create something solo that is expansive and experimental and interesting.”

The fact that Adebimpe is finally putting out a solo album at the same time as TV on the Radio’s return was entirely coincidental, and maybe not the best planning. In his telling, he had no idea that there would be so much interest in the band from fans and bookers, though now its name is among the larger fonts for festivals including Just Like Heaven, Primavera Sound, and Kilby Block Party. Sitek has declined to play in this wave of shows but is still in the band. Smith died of cancer in 2011, just after the group released its fourth album, Nine Types of Light. As to whether TVOTR will ever make new music together again, Adebimpe replies, “Right now, no, but I'm sure it'll happen.”

While Adebimpe has returned to music, he hasn’t totally put his other interests on pause again. He had a solo exhibition of his paintings at L.A.’s Gross Gallery in 2024 and has been working on a graphic novel for years. He’s started directing more music videos—a medium that he loves, but that is pretty thankless—handling each of the clips for Thee Black Boltz. When he and Zoby do two-man shows for the album in the fall, he’ll create all the background visuals.

As for his acting career, Adebimpe landed his first major role back in 2008 with Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married (he got married to Rachel and sang Neil Young’s “Unknown Legend” during the ceremony), though it hasn’t been until recently that he’s been able to go after roles in bigger productions. He has become a prolific voice actor, appearing on animated projects like Strange Planet, Lazor Wulf, and Pantheon. Director Jon Watts cast him in a small part as Peter Parker’s chemistry teacher in Spider-Man: Homecoming (years ago, Watts directed the video for “Wolf Like Me”) and then brought him on as the protective father of one of the young leads on the Star Wars TV series Skeleton Crew. In Twisters, he played a kooky weather nerd in Glen Powell’s ragtag crew. Adebimpe did a lot of self-taped auditions during the pandemic, exposing himself on a level that he’d previously avoided with his more sporadic approach to acting. “That’s some heavy rejection,” he says of the experience. “The trick that I used to pull on myself was just to be like, ‘Oh, they didn't call me back, they must not be making the project anymore.’”

When I meet up with Adebimpe in the beginning of March, the news (as is usually the case these days) is bleak. Various federal agencies are banning the use of certain words in an attempt to end “woke” government initiatives. The words include not only embattled terms like “DEI” and “Latinx” but also basics like “women,” “Black,” and “stereotypes.” Palestinian student activist Mahmoud Khalil has just been detained by ICE, despite having a green card permitting him to be in the United States.

Adebimpe knows that we are in a perilous time when it can feel like our country is being controlled by comic book villains with little regard for whom and what they harm. “I feel like America's the most ‘I'll tell you when I'm drunk’ country in the world right now,” he says. “It's just kind of like, ‘You're really fucking up. You’re really fucking up from the outside and the inside.’”

Within Adebimpe’s lyrics there are two coexisting perspectives: that everything is awesome and that everything is doomed. And that maybe the reason that everything is awesome is because everything is doomed. He calls himself an “optimistic nihilist.”

To build a kinder and more just world, he believes that maybe our old one will have to be destroyed. I don’t know how or when we’ll get there, but it gives me a little comfort to hear Adebimpe’s clear and compassionate voice again. “I think the good people will continue to get together and point out how absurd and cruel this shit is,” he says. “This whole thing’s going to fly into the sun someday. It just doesn't make sense.”