They say, “I love Bessie Smith.” And don’t even understand that Bessie Smith is saying, “Kiss my ass, kiss my Black unruly ass.” Before love, suffering, desire, anything you can explain, she’s saying, and very plainly, “Kiss my Black ass.” And if you don’t know that, it’s you that’s doing the kissing. —Amiri Baraka, Dutchman, 1964

The highest-grossing Black filmmaker in history has, understandably, many gods to serve. You’ve first got to put people in seats. And because this is America and Hollywood that we’re talking about, that means outflanking the inevitable doubts that your patrons can be all patrons—that your art can attract out-groups like it does a certain, often unnamed in-group. Ryan Coogler has spent much of the past decade doing just this: pulling the masses to the theater to watch films that were effortlessly coded for a subgroup, while maintaining a patent universality. For example, in 2018 my people flocked to Coogler’s Black Panther—clad in dashikis, kente cloths, and aso oke patterns—but my people alone had neither the means nor the ability to bankroll the film’s $1.35 billion box office return.

That’s a sea-to-shining-sea haul.

Like Spike Lee and John Singleton before him, though, Coogler has never just been in it for the bag. He wants to get under the hood, starting chiefly with the engine of what he rode in on. He believes in film “as a necessary pillar of society,” in cinema dedicated to adoring, critiquing, and exploring moments, groups, and places. In his library dwell portraits of Oakland sons extinguished by armed agents of the state (Fruitvale Station), spandexed Afrofuturist epics (both subsequent Marvel flicks), even a rebooted boxing franchise inflected with snapshots of the carceral system (Creed). But he also believes, just as much, in film for film's sake, in the alchemy made possible by the threading of sight and sound. He’s an auteur but also a craftsman, a fan, an admirer, and a student. No less a cultural excavator or showman than a maker of art of which the vibe is always, in one way or another: if you know, you know—and if not, you’ll get to find out.

Coogler’s latest film, Sinners, is a bluesy Southern gothic nestled in late-night vampire pulp that sustains and validates this same spirit. In the end, it’s a love letter to both a form and a subject.

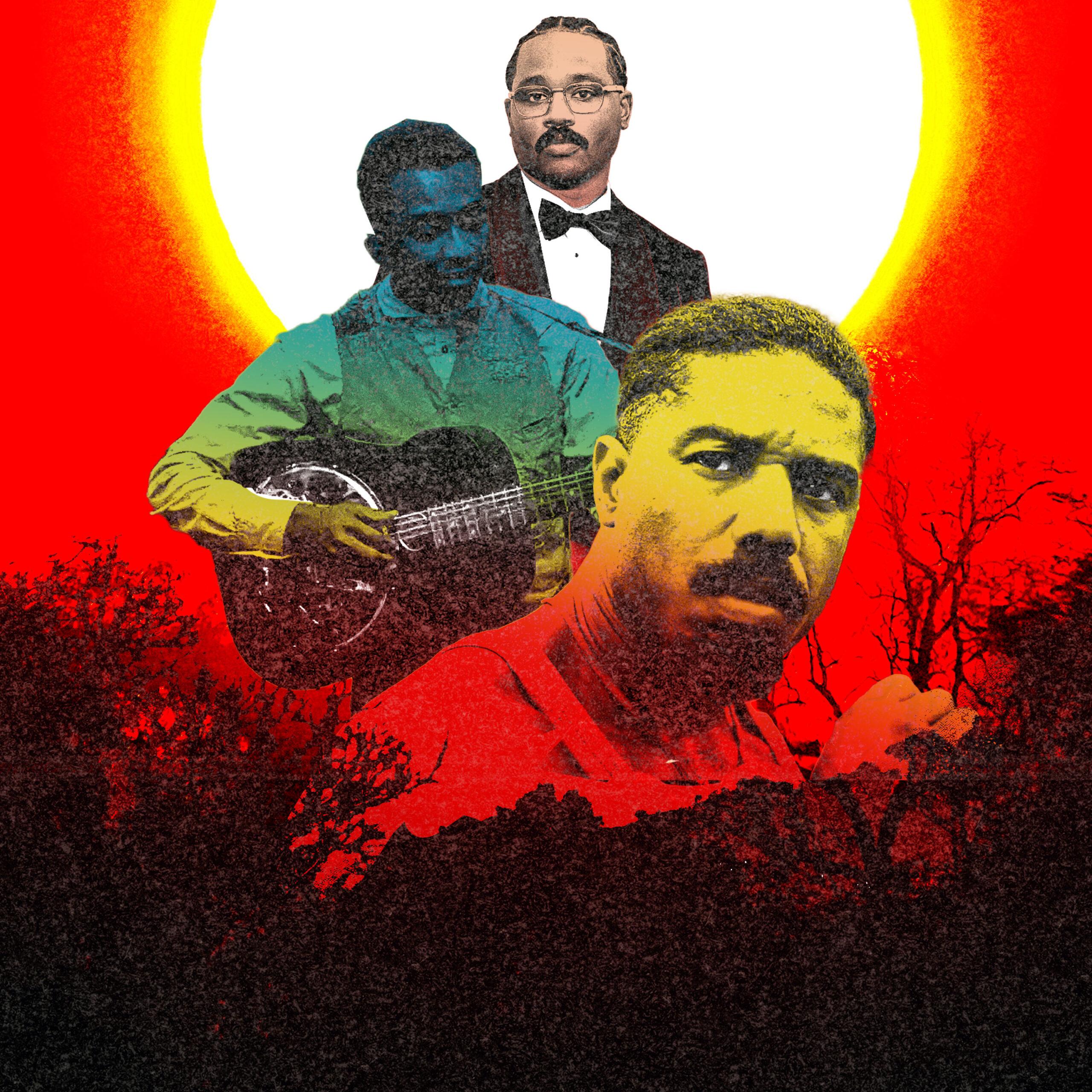

Sinners is, at face value, a period piece set in the mud-bound Mississippi Delta, though it drifts with ease among genres and tenors. It follows a day in the life of Sammie “Preacherboy” Moore (played by the 20-year-old newcomer Miles Caton in his first major role), a teenage aspiring bluesman with a voice as smooth as a pack of Marlboros, and his older twin cousins, Elijah “Smoke” and Elias “Stack” Moore (each portrayed by Coogler’s regular muse, Michael B. Jordan). The twins have just returned to their hometown of Clarksdale—the same place where blues legend Robert Johnson’s mythic deal with the devil went down—after serving in the First World War and working under (and stealing from) Al Capone’s Chicago criminal outfit. They’ve got a briefcase full of cash and a plan to open a juke joint. Most often, Sinners fixes its lens not just on the making of the music that forms its early subject matter, but also on the culture and community of the Delta itself. By the time the sun sets on this feudal Southern landscape and the horror elements of the story are firmly introduced, the tale evolves into a rumination on assimilation, family, and faith.

Sinners is a film about preachers, musicians, sharecroppers, root doctors, store owners, soldiers, and Klansmen—folks of all shades, inclinations, and motivations. Like the blues, its focus is common acts of striving, laughing, hustling, mourning, living. “These were just human beings trying to make it under a backbreaking form of American apartheid,” Coogler recently told The New Yorker, of rock ’n’ roll’s underpaid and pilfered-from progenitors. “That humanity, you know, that deserves epic treatment, too.” Central to its mission is reanimating the intricate, thorny world that birthed America’s chief cultural export. It’s not a movie that’s trying to prove or convince you of anything, but rather one wholly devoted to building on what inspired it, paying homage, keeping it funky and freaky, entertaining as hell.

Wide-angle shots of upland cotton rows are interspersed with dusty main streets, muggy backwoods, feed-room dance floors. The subtext of the supernatural—brought with aplomb via the undead Irishman Remmick (Jack O’Connell)—is that brand of occult flirtation that took Johnson from the crossroads to the mythical annals of blues history, turned Celtic dance and the African gioube into minstrel staples: Who, exactly, puts the “folk” in folk tunes? Whom do they belong to? At what cost? The movie is filled to the brim with song and dance. One scene in particular, a mélange of a century’s worth of Black American soundscapes, is likely to rack up a few awards, but there’s an eerier jig that takes place in the moonlight that’ll leave folks questioning whether Blackness or whiteness is actually Sinners’ target.

Coogler, like many children of the Great Migration, is fluent in both the language and customs of the old country. His Mississippi-born uncle on his pops’s side put him on to Old Taylor whiskey and chitlin’ circuit deities. “He lived down the street from me, essentially, so I spent a lot of time with him," Coogler recently told The Atlantic. “This film was a love letter to him and that exploration of the music that he was obsessed with.” In a similar way, aesthetically, Sinners is a paean to his cinematic forebears, guides, and peers.

Much like Lee’s Do the Right Thing feels like a summer heat wave, Sinners is drenched in the blues. The color palette, with its emphasis on indigo and scarlet, retains a dusty clarity not unlike that of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer or Jordan Peele’s Nope. The costumery and props capture the lived-in authenticity of Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club. The musical notes, chiefly the depiction of the twins’ central juke joint, recall the down-home comfort of both Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple and Joel and Ethan Coen’s O Brother Where Art Thou (to say nothing of the influence of a short film like Steve McQueen’s tender Small Ax featurette Lover's Rock). There’s gore as delightfully absurd as a Quentin Tarantino outing’s, world-building as enveloping as Julie Dash’s Gullah-inflected Daughters of the Dust, and horror set pieces arranged gracefully enough to evoke John Carpenter’s best.

As ample as Sinners’ cinematic influences are (it doesn’t shy away from the From Dusk Till Dawn comps), Coogler has copped to an array of other inspirations away from the screen: Stephen King’s use of literary tension and restraint. Amiri Baraka’s portraits of the blues as inextricable from “the Negro’s adaptation to, and adoption of, America.” The Delta subgenre’s habit of toeing the line between pleasure and sin, faith and liberation. It doesn’t take a musicologist to connect a certain post-credit-landing blues titan’s trademark use of silence to transfix anyone in earshot to Sinners’ own intentional spurts of stillness. Taken in a vacuum, none of these threads should necessarily lead to one another; in Coogler’s hand, they pluck out a savory tune.

That ain’t to say that the flick is Sunday school perfect—Sinners has got rough edges, blurred lines, and a coda that renders a few things moot—but it is a stunning, entrancing, spooky work. Just his fifth full-length project, Sinners, too, carries immense stakes not just for Coogler’s wallet or his oeuvre but also for a wobbly industry at large. As part of the contract that brought it to the beleaguered Warner Bros. Studios, the director procured a copyright deal that will see ownership for Sinners revert back his way in the spring of 2050. One exec from a rival studio hailed it as the potential “end of the studio system.”

Coogler said his “only motivation” was ensuring that the single greatest mainstream examination of the single greatest theft in the history of American popular culture didn’t fall for the same ole tricks. The man has eyes and ears. He’s hip to what he’s got in hand. With Sinners Coogler rolled straight to the crossroads—a path that, if you know, you know.