Across a Hall of Fame career that spanned four decades, six franchises and nearly 2,000 games, George Karl accumulated a staggering number of wins and losses, along with a fair share of regrets: timeouts he should have called, substitutions he should have made, relationships he should have mended. None of it compares to the grave error he made in February 2015.

Karl was 63 then, a respected elder in the coaching community, with enough highlights to fill a Ken Burns documentary. He’d taken the Seattle SuperSonics to the 1996 NBA Finals (against Michael Jordan), guided the Milwaukee Bucks to the 2001 Eastern Conference finals (against Allen Iverson) and presided over two of the greatest seasons in Denver Nuggets history. He’d won more than 1,000 games. He’d earned tens of millions in salary. He’d beaten cancer along the way—twice. His entry into the Hall of Fame was virtually assured. By 2015, there was little left to prove.

Yet there was Karl, sitting before the assembled Sacramento media, having just taken a job with one of the league’s most dysfunctional franchises, for one of its most meddlesome owners, to coach one of its most volatile stars. It did not go well. Fifteen months later, after dozens of losses and countless clashes with All-NBA center DeMarcus Cousins, Karl was fired by Kings general manager Vlade Divac and team owner Vivek Ranadivé.

The messy ending was wholly predictable, perhaps inevitable.

“Sacramento was not the right decision to make,” Karl says today, “but I didn't know what I didn’t know. I didn't know DeMarcus’s abilities, negative abilities. I didn’t know the ownership and how dogmatic and dictatorial he was.” It turned out to be Karl’s final coaching stint—and perhaps his greatest regret in a long and storied coaching career. “I probably should have walked away,” he says.

To be sure, Karl did not need the job, or the money. He surely didn’t need the headaches, the stress, the scrutiny, the late nights, the long flights, the weeks spent away from family, the missed birthdays and holidays, the sheer, exhausting relentlessness of the NBA schedule. Yes, as Karl says now, he should have walked away.

The thing about walking away is, it’s really, really, really hard.

“When you’re in it, you’re addicted to the juice of the game,” Karl says. “When I became a coach, I got the juice of coaching and having success and trying to be the best at it. And I was addicted. I was addicted to trying to be a hell of a coach. And in the end, as you look back on it, it’s probably not healthy.”

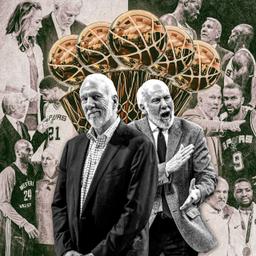

Unhealthy, perhaps. But also: damn near irresistible. It’s a universal sensation among NBA coaches, one they uniquely understand. Which is why none of them were surprised to see Gregg Popovich, at age 75, still coaching the San Antonio Spurs last fall … and why no one would have been entirely shocked had Pop returned to the sidelines again next season, with all his trademark feistiness, despite missing most of this season after suffering a mild stroke last November.

That possibility lingered until last Friday, when Popovich at last announced he would be stepping down as head coach and focusing on his role as team president, a title he has quietly held since 2008. His health was the primary reason—a stark reality that became evident to the public on Monday, when Popovich appeared at a press conference for new head coach Mitch Johnson. Pop moved gingerly, spoke softly and revealed his new role with a T-shirt that read, “El Jefe,” Spanish for “the boss.”

“I’m no longer ‘Coach,’” Popovich said. “I’m ‘El Jefe.’”

It’s addictive. It’s exhilarating, it’s incredible, the highs and the lows. You just feel like you’re alive, and you can’t match the thrill of victory and defeat and everything in between. You just can’t match it.Steve Kerr

By the time of his retirement—a word the Spurs did not use—Popovich had already outlasted every franchise legend of the last quarter century, from David Robinson to Tim Duncan to Kawhi Leonard, as well as some 300 head coaches who had come and gone across the league since he first took the Spurs’ reins in 1996. He’d coached far longer than friends and confidants ever anticipated, and had become the oldest head coach in NBA history. He’d lost none of his passion or competitive edge. And he’d shown no inclination to retire, even after enduring six straight losing seasons on the heels of 22 consecutive playoff appearances. If anything, he’d been reinvigorated by the arrival of another young superstar, Victor Wembanyama, in the 2023 draft. By then, the words “Popovich” and “Spurs” were so tightly intertwined that it seemed like he’d coach them forever.

“He coached until pretty much he couldn’t, in a sense,” Leonard told reporters over the weekend. “It shows how much dedication he had to the game, how much he loved the game, and how much he gave to the game.”

So until the official announcement landed, it still seemed possible we’d see Pop roaming the sidelines again. He’d endured countless setbacks and rebuilds and personal losses, coming back every time. That’s how powerful the pull of the game is.

“It’s addictive,” Golden State Warriors coach Steve Kerr told me in March. “It’s exhilarating, it’s incredible, the highs and the lows. You just feel like you’re alive, and you can’t match the thrill of victory and defeat and everything in between. You just can’t match it.”

It would feel hyperbolic to call coaching an actual addiction—if it weren’t for all the coaches who invoke the word themselves, or in some cases describe the very sensations the word implies. That the job gives them a high that nothing else can replicate. That all the physical, mental and emotional strains are absolutely worth it. Because not coaching feels worse.

You can see it across the league, across the age spectrum, and across decades:

- Larry Brown, a Hall of Famer and one of basketball’s most decorated coaches, was 77 when he took a head coaching job in Italy in 2018—and 80 years old when he joined Penny Hardaway’s staff at the University of Memphis.

- Health concerns, including chest pains and coughing up blood, forced Tyronn Lue to take an extended leave of absence from coaching the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2018—but he returned for the playoffs that spring.

- Steve Clifford, suffering from sleep deprivation and severe headaches, took a leave of absence from the Charlotte Hornets that same season—but he too returned and kept coaching.

- Kerr struggled through back troubles in 2015, missed the first 43 games of the 2015-16 season due to complications from surgery, and later missed several weeks of the 2017 postseason (including Game 1 of the Finals) because of further complications. He is, of course, still coaching the Warriors today.

“I’ve talked to so many coaches over the years who say, like, ‘I’m not a lifer, I’m not going to do this [forever],’” Kerr said. “And I was that exact guy when I signed with the Warriors [in 2014]: Maybe I’ll coach for five years, coach out my contract, and then maybe go back to TV. And this is Year 11. And I’m still going to tell you, I’m not a lifer. And I have no idea when I’m going to hang it up, because I love it so much. It’s amazing. It’s sooo fun, it’s so emotional, and … it’s addictive.”

There’s that word again. Merriam-Webster defines addiction as “a compulsive, chronic, physiological or psychological need for a habit-forming substance, behavior, or activity having harmful physical, psychological, or social effects and typically causing well-defined symptoms (such as anxiety, irritability, tremors, or nausea) upon withdrawal or abstinence.” Coaching isn’t always harmful, of course, but the job is taxing enough that it can be. The more general, secondary definition of addiction—“a strong inclination to do, use, or indulge in something repeatedly”—surely applies to the profession.

Think of Tom Thibodeau, now the NBA’s oldest active head coach at 67, in his 33rd season on an NBA bench (including 20 as an assistant); or his mentor, Jeff Van Gundy, who at age 63 returned to the bench this season as an assistant for the Clippers after 16 years as a broadcaster; or Doc Rivers, also 63, who left the relative comfort of the ESPN broadcast booth in the middle of the 2023-24 season to join the Milwaukee Bucks, his fifth head coaching job in the past 26 years. (Or consider their football peers, such as Pete Carroll, who was recently hired by the Las Vegas Raiders and at age 73 will be the oldest coach in NFL history; or Bill Belichick, also 73, who took the head coaching job at the University of North Carolina after just one year of “retirement” following his departure from the New England Patriots.) None of them need the anxiety and aggravation, but they keep coming back.

“To me, the definition of addiction is: Is what you’re doing leading to negative consequences?” says Brian Levenson, a mental-performance coach with a master’s degree in sports psychology, who works with athletes and coaches, including clients in the NBA and NFL. “How many athletes have used the word obsessed? And I think coaches would probably say the same thing, that you’ve got to be obsessed [to succeed]. So where does obsession turn into addiction? And where does it become unhealthy? … I think each coach could answer that for themselves.”

Coaching, especially at the pro level, practically requires an extreme passion and attention to detail as a gateway to entry. Nearly all the great coaches are grinders, obsessing over film and analytics and player tendencies. If coaching in the NBA is indeed an addiction, perhaps it’s because the profession attracts the very personality types who are prone to obsession.

When veteran coaches talk about what keeps them coming back, the games are often an afterthought. For some, it’s about the preparation, the practices, the strategizing. For others, it’s the thrill of matching wits against the game’s greatest minds. Winning, especially in the playoffs, brings its own high. But the conversation with every coach eventually comes back to camaraderie, to the bonds they build with their assistant coaches and their players.

“The challenge of just trying to achieve something with a group of people,” Kerr says. “The emotion of winning and losing, the exhilaration of a winning locker room, it’s incredible. The devastation of a tough loss. But then you commiserate, and so in the end, you’re doing this with a group of people. And if you do it right, or if you’re lucky enough, you get to do it with people who you love. … You come in, we talk shit to each other, we make fun of each other, because that’s how guys tell each other they love each other. And so you build these incredible relationships through the fire of competition, and it’s really hard to match that anywhere else in life.”

Throw in a reference to a Michelin-starred restaurant and a great bottle of wine, and that quote could have come from Popovich, or any of his disciples—a group that would include Kerr, who played for the Spurs for four seasons and counts Pop as a key mentor. Like Pop, Kerr also places a high value on work-life balance, even amid the chaos of an NBA season, believing that too much focus on the game (i.e., the coach-who-sleeps-in-his-office model) is unhealthy. Kerr wants his players and staff to get a mental break sometimes. But he also relishes the time with them.

Indeed, the first thing Brown cites when asked about the joys of the job is getting together with his assistant coaches.

“I looked forward to getting up in the morning and meeting with my staff,” he says. “I loved practice. I think very few people could experience the joy that I had just going to practice and being around my staff and being around the players and watching them grow.” The actual games, by contrast, “were tough for me,” Brown says: “I always had this fear that maybe I hadn’t prepared my team for something that might happen.”

Brown has always viewed himself as a teacher of the game, a role he relishes to this day as an informal adviser to countless protégés across the country. The same goes for Karl, who, like Brown, played collegiately at North Carolina under the legendary Dean Smith and absorbed his philosophy of selfless play.

“I really felt the one thing I did well, I took ‘the Carolina Way’ [as Smith called it] and tinkered and manipulated it into a Carolina Way in pro basketball,” Karl says. “The we was much more important to me than the me.” The task of instilling those values, Karl says, is what kept him coming back year after year, from his first NBA head coaching gig with the Cavaliers in 1984 to his stints with the Warriors, Sonics, Bucks, Nuggets, and Kings.

For Clifford, it’s about “the camaraderie, the study, the discussions, the meetings,” but also the most essential aspect of NBA competition: “I just think it’s the ultimate challenge if you’re a basketball coach. You get to coach and coach against the 450 greatest players in the world. You see exceptionality every day in practice, every time there’s a game. You coach every night against great coaches.”

Clifford adds: “I’m not sure there’s many greater highs in life when you’re a coach than walking out of an arena or walking off a court on the road, when you’ve maybe had a good day of practice, a good shootaround, and played a really good game against a terrific opponent and won the game.”

It’s a high that Clifford, now 63, hasn’t experienced in 15 months, when his Hornets took a 120-110 victory over the Cavaliers in the final game of the 2023-24 campaign. He resigned after the season—a decision he’d announced two weeks prior—to shift into an advisory role in the team’s front office. His health was a major consideration.

During his first stint with Charlotte, in 2013, Clifford had to take a brief leave of absence after having surgery to place two stents in his heart. Four years later, Clifford had to take a 21-game leave of absence that was attributed to “sleep deprivation,” but that he now says was because of severe headaches related to the sleep issues.

“They made me walk away and take a break,” he says. When he did return to work, Clifford sacrificed a major part of his old routine—watching games or game tape on his off nights at home.

“One of the things that the neurologist and our team doctor made me do, and it helped me a lot, was when I left the office, never take work home,” Clifford says. “And I never watched games at night, not even college games. So I became more of a movie watcher or go for walks or whatever, and it actually made a pretty significant difference.”

Clifford coached five more years—three in Orlando and two in Charlotte—without any major health problems. But the stresses of the job, and way too much losing over his final years, eventually became too much. “I got to the point … where it was all too much for me,” he told reporters last year. “I need time away from coaching.”

Every coach has stories of waking up at 3 a.m. with a sudden revelation of a play they should run, or a regret over a decision they made hours earlier. That’s if they ever got to sleep at all.

“The things that keep you up at night,” Clifford says, “are you’ve lost three in a row, and all of a sudden, you’re going to Golden State, or you’re going to Boston or Cleveland. It is hard to get a good night’s sleep when you know how hard or how well your team is going to have to play to win.”

“When my work day gets done, I’m excited for the next day. [It’s] something I felt very deeply in my soul last spring, that I was supposed to be coaching. And every experience so far has reinforced that—even the bad, tough days. I mean, those are inevitable in an NBA season. So I love it all.”JJ Redick

Today, Clifford says, he feels “much healthier than I have in a long time,” while working for the Hornets as a senior adviser in a much less taxing and time-consuming role. His duties include advising head coach Charles Lee, a longtime friend now in his second season at the end of the bench, along with some scouting and various projects. “I’m getting my basketball fix,” he says, though he admits that nothing can replace the thrills of daily competition. “I definitely miss the coaching.”

In 2018, a few months after Clifford took his second leave of absence in Charlotte, Lue announced he’d be stepping away in Cleveland because of anxiety and chest pains that he later attributed to poor eating and sleeping habits. He missed nine games, then returned to guide the Cavs back to the NBA Finals. Lue, who has been coaching the Clippers for the past five seasons, has generally enjoyed good health in recent years, though he missed a handful of games this season because of back pain.

The stress and the lack of job security remain ever-present for anyone who walks the NBA sidelines, even the most successful coaches. In the final two weeks of the 2024-25 season, two head coaches of playoff-bound teams were abruptly fired—Michael Malone of the Denver Nuggets and Taylor Jenkins of the Memphis Grizzlies—prompting a reporter to ask Lue, simply, Why would anybody want to be a head coach in this league?

“They pay well,” Lue said with a chuckle. “It’s a great job, especially when you reach the pinnacle of winning a championship.”

Lue reached that pinnacle with the Cavaliers in 2016, against Kerr’s Warriors. Kerr, of course, has won four titles as a head coach, though that hardly protects him from the same howls and criticism and second-guessing that every coach at this level endures. But it’s the internal second-guessing that truly haunts him, the nights when he feels his own decisions cost the team a game.

“It’s the most miserable feeling in the world,” Kerr says. “And those are the nights you’re like, What the hell am I doing? Why am I doing this? But then you gotta get off the mat, and you gotta go to work, and you gotta get the troops together. … And that in itself is really exhilarating. When you rally them, and then you respond and you get a win? Now it’s like the pendulum swings, and you’re like, Oh, this is the greatest feeling of all time,” he says, adding with a laugh, “It’s totally unhealthy.”

Kerr chose this life in 2014, leaving behind a highly successful—and far less stressful—career as a game analyst with TNT. Last summer, JJ Redick followed a similar path, resigning from ESPN’s lead broadcast team —and his own wildly successful podcast—to become head coach of the Los Angeles Lakers, which might be the most high-pressure job in the league. But when asked in early March if he had any moments of second-guessing the decision, Redick said flatly, “Not a single one.”

“When my work day gets done, I’m excited for the next day,” Redick said. “[It’s] something I felt very deeply in my soul last spring, that I was supposed to be coaching. And every experience so far has reinforced that—even the bad, tough days. I mean, those are inevitable in an NBA season. So I love it all.”

Redick is 40, still young for an NBA head coach, without the accumulated battle scars of, say, a George Karl or a Larry Brown or a Gregg Popovich. He just got his first real taste of failure as a coach last week, when the third-seeded Lakers were ousted in the first round by the Minnesota Timberwolves. With it came the first real barrage of criticism about his decision-making—and some testy responses from Redick. And yet, given how most coaches are wired, it’s likely that Redick was second-guessing himself far more intensely than fans and pundits were.

It’s also likely that, whenever his coaching journey winds down, Redick will remember more of the highs than the lows. When Karl reflects on his four-decade run, it’s not the losses that still haunt him as much as the lost time with friends and family, the birthdays and holidays missed. It’s the all-consuming nature of the job—the addiction commandeering too much of his consciousness and the calendar.

“I wish I would have gotten out earlier and learned to have a life outside of basketball that I could enjoy,” Karl says. “Now I’m at an age where I can’t travel as much as I want to travel. My health probably stops me from doing a month of golf in Thailand, like I’ve been invited to do.”

Yes, Karl says, he misses coaching. He’s still learning how to keep himself busy. But he’s savoring the time he now gets with his family. “You get to know your kids better,” Karl says. “Your kids go from being kids into being best friends. You have grandkids. And fortunately for me, I have a lot of assistant coaches still in the league; my coaching-tree guys come through Denver all the time, so I can always touch the game. My son [Coby] is a coach. I had a ball when he won championships in the G League, and I got to sit in the locker room and watch my kid coach. And that was a gift. My last child [daughter Kaci Karl] went to the NCAA Division III soccer championship two years in a row. That’s a gift, and I got to witness that, but I wouldn’t have witnessed it if I stayed in coaching.”

So when Karl, speaking in early April, considered the decision facing Popovich, his view was unambiguous, informed by his own health battles and his struggle to break free of the job.

“My wish is that he retires,” said Karl, who coached alongside Popovich with the U.S. national team in the early 2000s. “He’s still a damn good coach. I just wish he would celebrate by retiring and trying to find a purpose somewhere else. We’re talking about the same addiction that made me go to Sacramento. I have the feeling he has the same addiction, that ‘I gotta come back, I gotta be loyal to my San Antonio people.’ Pop, you don’t have to be loyal to anybody. You’ve given us a great, great career.”

“I wish I would have gotten out earlier and learned to have a life outside of basketball that I could enjoy.”George Karl

For the coaching lifer, it’s sometimes hard to discern where basketball ends and, well, where everything else begins. Basketball is life, as the saying goes. What other purpose is there? What does life without it even look like? Feel like? Sound like? When Larry Brown rhapsodizes about hoops, he invariably invokes a pet phrase about wanting to “smell the gym.” Basketball satisfies all of the senses.

That’s why Brown—who hired Popovich as a Spurs assistant coach back in 1988 and remains a close friend—worried just as much about the consequences of walking away as of staying.

“I think the guy has a gift, and he’s helped so many young people,” Brown told me in April. “I hope he can continue to do it. But I don’t want anything bad to happen. … If there’s something that’s in your DNA that you’ve done and you’re passionate about it, and it’s been such a big part of your life, and then all of a sudden you stop, I don’t know how that affects you. I just want him to be healthy. My hope is that he’ll be back on the bench helping young kids get better.”

After all, that’s all that Brown says he ever wanted to do: help players get better. The national championship with Kansas in 1988 was a thrill. The 2004 NBA championship with the Detroit Pistons was a joy. Brown’s résumé would be the envy of nearly anyone who coaches the game—but to this day he insists his motives were as basic and pure as can be: “I just wanted to share what I was taught.”

It’s why Brown still advises friends and protégés whenever he gets the opportunity. It’s why, on any given winter day, you might spot him in a high school gymnasium in Charlotte, watching his granddaughter’s junior-varsity team or dispensing wisdom to the local coaches. It’s why Brown, at age 82, accepted an offer from then–University of Washington coach Mike Hopkins to work as a special assistant in 2023. It’s why Brown was on the court, getting ready for practice, when a freshman player accidentally ran him over, causing a minor injury that required some rehab and effectively ended Brown’s time there.

It’s why, looking back, Brown now says, “I shouldn’t have left SMU” over a contract dispute in 2016. “I could have stayed there forever,” he says. “I kind of regret leaving there. I think if I didn’t leave there, I would still be there.”

Still there? Still coaching? At age 84?

Yes, Brown says. Still.

So, is coaching an addiction?

“No,” Brown protests, “It’s not that.”

What, then?

“I just think that when you’re somebody like me, and you were able to play with great players and be coached by unbelievable coaches and sat next to unbelievable coaches, and then coach unbelievable players, you have a lot to share,” Brown says. “I’d still love to help somebody in some way.”

In retirement, Karl has taken up journaling and worked on a documentary about the ABA. Brown occasionally plays golf. Perhaps Popovich will find some new calling. But they all know that nothing can replace the competition and the camaraderie and the exhilarating chaos of the NBA grind. Nothing beats the smell of the gym.