At the end of Casablanca, Humphrey Bogart’s world-weary American club owner, Rick Blaine, watches the woman he loves fly away from him forever with her husband. It’s a noble sacrifice in a movie about the complicated virtue of doing the right thing. If you love somebody, you have to be ready to let them go.

As a consolation prize, Rick walks off into the fog with a local cop, Louis (Claude Rains), who’s recently experienced his own moment of clarity, switching allegiances away from the corrupt Vichy regime. No less than Rick, Louis is a cynic trying to reclaim his wayward idealism; their mutual understanding in the final scene suggests a meeting of kindred spirits. “Louis,” says Rick tenderly as they wander past the camera into a better tomorrow. “I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

The last line of Casablanca is a classic. It’s been guaranteed inclusion on pretty much every list of the greatest-ever screen dialogue, including coming in at no. 20 on the American Film Institute’s “100 Years…100 Movie Quotes,” just ahead of Hannibal Lecter’s anecdote about eating an overzealous census taker. To paraphrase another keeper from the film’s Oscar-winning screenplay, Rick’s words continue to work their magic, no matter how much time goes by. This is partly because of Bogart’s delivery, which is so hoarse and deep that Rick’s promise of solidarity seems to come directly from his heart, the sound of sarcasm giving way to sincerity. It’s also partly because the line draws a bead on an important theme, which is, of course, that Dudes Rock.

Andrew DeYoung’s new film Friendship doesn’t have much in common with Casablanca beyond some eminently quotable dialogue: Since seeing the movie together last fall at the Toronto International Film Festival, a friend and I have been texting one particular non sequitur back and forth at least a couple of times a month, like some kind of magical incantation. (You’ll know it when it brings the house down.) Friendship is a movie that takes risks with style and tone and makes them pay off, transforming viewers into rubberneckers at what feels, at times, like a psychological car wreck.

The crash test dummy in this case is Craig (Tim Robinson), a woebegone suburban dad who obsessively gloms onto his charming new neighbor, Austin (Paul Rudd), as a potential bestie. The vibes, as they say, are off; the more Austin tries to ignore Craig, the closer Craig gets to him, and the film makes skin-crawling comedy out of the resulting claustrophobia. Skillfully written and directed by DeYoung, a young veteran of early 2000s sketch and internet comedy making his feature filmmaking debut, Friendship has been shaped to the idiosyncratic rhythms of its star, who’s peerless when it comes to playing contemporary men coming apart at the seams. Craig is unhinged, but the movie is drum-tight, juxtaposing balls-out absurdity against a trenchant exploration of masculine dynamics. The result is something between a hallucination and a dissertation, wryly deconstructing contemporary bromantic tropes while plugging into the metaphysics of the buddy comedy—a tradition almost as old as Hollywood itself.

Comedy duos were a staple of the 1920s and ’30s, drawing on the sturdy, vaudevillian dialectics of the straight man and the oaf, each the other’s distorted mirror image. “Here’s another nice mess you’ve gotten me into,” says Ollie to Stan in The Laurel-Hardy Murder Case, a line that has become shorthand for both Laurel and Hardy’s pioneering output and the idea of buddy comedies in general. “The world is full of Laurel and Hardys,” said Oliver Hardy when asked to reflect on his success. “There’s always the dumb, dumb guy, who never has anything bad happen to him, and the smart guy who’s even dumber than the dumb guy, only he doesn’t know it.” Laurel and Hardy’s joint stardom bridged the gap between the U.S. and the U.K. (Laurel was born in Lancashire), as well as the silent and sound eras. At their best, they tapped into something profound: the need for solidarity in a hostile world.

Where do-it-all auteurs like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton styled themselves as loners—isolated Davids staring down angry Goliaths—the odd-couple pairings of Laurel and Hardy and Abbott and Costello (and trios and quartets, factoring in the Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers) offered united fronts, as well as the Peter Pan-ish promise of being Lost Boys for life. Hence the observation of film historian David Thomson, who ties the prevalence of male comedy duos to entrenched, All-American attitudes and anxieties around gender. “There are very few buddy movies in British or French films,” he wrote. “You just wouldn’t see three Englishmen behave the way American men do, who are truly happiest when they are together with other men.”

In 1940s buddy comedies, slapstick blundering gave way to urbane sophistication, exemplified by the films of Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, whose Road movies profitably wrought surface variations on a simple setup: two giant stars playing thinly veiled versions of themselves wandering through backlot paradises, slinging jokes, singing songs, and playfully demolishing the fourth wall. In a movie like 1942’s The Road to Morocco—a story set just down the road from Casablanca—Hope and Crosby gleefully sent up adventure-film conventions as well as their own celebrity, splitting the difference between smugness and self-deprecation in ways that would prove hugely influential. Exhibit A: Frank Sinatra’s Rat Pack, which took the boys-club mentality and expanded it into a mini showbiz empire, with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis as its in-house odd couple. Occasionally, Martin and Lewis found themselves at the center of worthy movies, like 1955’s sublime Artists and Models, with Dean as the archetypal, smooth-talking charmer and Jerry pulling faces as his hyperactive roommate. But the most ingenious distillation of Martin and Lewis’s iconic suave-vs.-slob dynamic came after their breakup, with the latter’s dual role in 1963’s The Nutty Professor. Playing a mad scientist who subdivides himself into a klutz and a ladies’ man, Lewis took pains to impersonate—and skewer—his former pal by making the second persona into a grotesque parody of showbiz lechery and insincerity. His Martin manqué’s name: Buddy Love.

The most pivotal buddy movies of the 1950s and ’60s weren’t comedies: Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958) and Norman Jewison’s Oscar-winning In the Heat of the Night (1967) dealt explicitly with racial tensions, suggesting that sustained partnership—whether between chain-gang convicts or mismatched detectives—could yield understanding. In the Heat of the Night in particular anticipated the black-cop, white-cop dynamics of ’80s action comedies like 48 Hrs. and Lethal Weapon. There was also explicit sociology in Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), which revised the straight-man-goofball dichotomy by making its heroes both beautiful losers. Call it The Road to Mardi Gras, with Hopper’s Billy and Peter Fonda’s “Captain America” as shaggy, doomed anti-establishment stand-ins for Hope and Crosby.

Swapping out horses for motorcycles, Easy Rider was a revisionist, modernized Western. That same year featured Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight as mismatched schemers in Midnight Cowboy, with its metaphorical sight gag of a 10-gallon John Wayne type adrift in Times Square, as well as Paul Newman and Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The spectacle of the two handsomest, most charismatic movie stars in America clowning around together at magic hour was potent stuff; despite the presence of Katharine Ross as Sundance’s love interest, it seemed the boys only had eyes for each other. “I would much rather see a picture about two homosexual men in love than see two romantic actors going through a routine whose point is that they’re so adorably smiley butch that they can pretend to be in love and it’s all innocent,” wrote Pauline Kael in her review of Redford and Newman’s subsequent, two-against-the-world period piece The Sting, effectively pegging the sublimated desire onscreen while echoing the larger critique of the era’s myriad his-and-his masterworks: that for all its revolutionary sentiment and progressive rhetoric, the New Hollywood was very much a boys’ club.

With this in mind, the greatest American buddy comedy of the 1970s is an outlier: Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky, a dark-night-of-the-soul farce indebted, both practically and spiritually, to the scabrous, warts-and-all-emotionalism of its star John Cassavetes’s directorial efforts. The Philadelphia underworld milieu suggests a post-Godfather genre film—the plot involves a contract killer—but May’s movie is more like an anthropological study of male vanity, insecurity, and desperation, embodied separately but equally by Peter Falk’s rueful Mikey and Cassavetes’s hysterical Nicky. “I’d do anything for you,” says Mikey after Nicky has dragged him into a dangerous situation involving a local mob boss. “Anything … and unless you’re sick or in trouble, you don’t even know I’m alive.” Leave it to May—a fearless nonconformist who spent her career being betrayed, blacklisted, or otherwise fucked over by the studio system—to illuminate the nature of masculine codependency, a fugue of paranoia and melancholy spiralling endlessly out of control until death do they part.

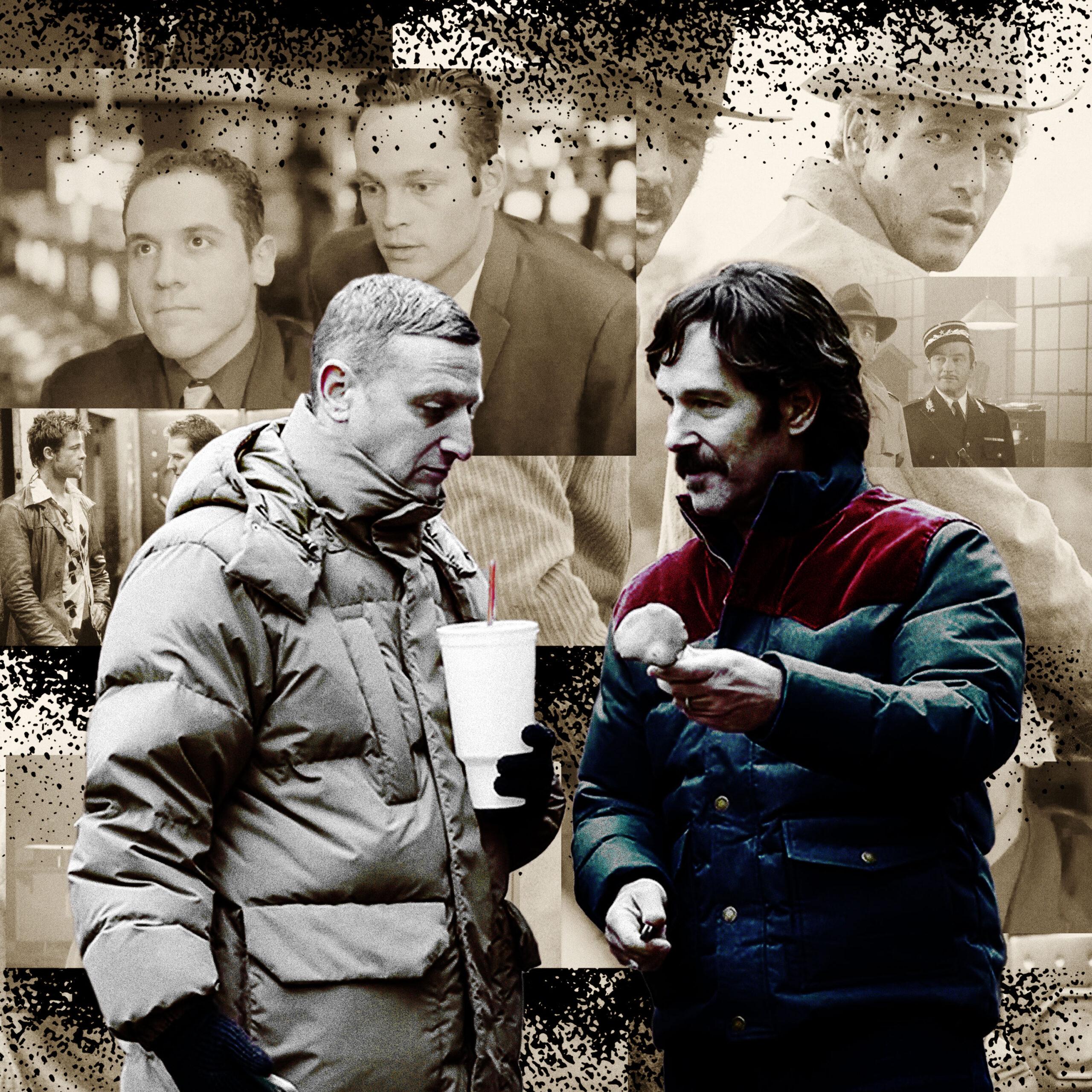

It’s probably a coincidence that a Mike and a Nikki figure into Doug Liman’s career-making 1996 buddy comedy Swingers (the latter is a woman who gives Jon Favreau’s lovelorn Mike her phone number at a bar, leading to a classic answering-machine meltdown). Favreau wrote the script, but the breakout star was Vince Vaughn as the flamboyant, endearingly sleazy Trent, a party monster who imagines himself as the reincarnation of Dean Martin (or something like it). With its modest production values and highly quotable script, Swingers fit nicely in an indie zeitgeist in thrall to the likes of Kevin Smith and Quentin Tarantino. So did Good Will Hunting, the shared primal scene of Matt Damon and Ben Affleck’s careers and, among other things, a buddy comedy par excellence. Robin Williams may have won an Oscar for his cuddly psychiatrist act, but the best scene in the movie is the late, fateful exchange between Will and Chuckie, which inverts the possessive mania of Mikey and Nicky for something more akin to the chivalry of Casablanca. “Hangin’ around here is a fuckin’ waste of your time,” Chuckie says to his genius-next-door pal, telling him, with love, to get lost for his own good. Chuckie gets his wish when Will skips town and Affleck sells his heartbreak at what looks like the ending of a beautiful friendship. Somewhere, Rick Blaine was nodding appreciatively.

Where Good Will Hunting launched a pair of A-list movie star careers, David Fincher’s Fight Club—the most cerebral buddy comedy of the late ’90s—complicated its leading man’s charisma, weaponizing Brad Pitt’s preternatural beauty in ways that predecessors like Newman and Redford hadn’t really dared. Conceptually, Fight Club’s tale of inseparable domestic terrorists was less an outlaw picaresque like Butch Cassidy than an oblique remake of The Nutty Professor, with Pitt’s Tyler Durden revealed as the alter ego of Edward Norton’s nameless narrator—a grungier Buddy Love acting out his creator’s subconscious fantasies of physical and sexual dominance. Few contemporary movies are as successfully booby-trapped as Fight Club, which works equally well as a satire of American psychosis and an embodiment of it, and also a stealth update of Laurel-and-Hardy’s cozily antagonistic ethos; holding himself at gunpoint, the Narrator has nobody to blame but himself for the fine mess he’s gotten himself into.

Pitt riffed on his role as Tyler Durden in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood. Cliff Booth may not be a figment of Rick Dalton’s imagination, but they have a similarly symbiotic relationship, with Cliff’s virtuoso violence as a mutual fail-safe mechanism. There’s also a little bit of Fight Club in Friendship, which pivots on a sequence involving amateur fisticuffs—a bonding ritual almost always guaranteed to go wrong. (Another point of convergence: Friendship’s slightly Fincher-ish forays into corporate satire, including a pretty spectacular bit of anti-product placement for Subway.) A more obvious point of comparison for DeYoung’s film would be the last decade and a half of Apatowian bromances, a lineage cinched by the casting of Rudd, whose work in The 40 Year Old Virgin, Knocked Up, Anchorman, and I Love You, Man hangs over his performance. (My own pick for Rudd’s best-ever buddy comedy is David Wain’s sublime Role Models, in which our hero pilots a monster truck while telling Seann William Scott, “I want to rock and roll all night, and part of every day”). In Friendship, Rudd’s stalwart presence helps to keep things grounded while Robinson flies off the handle; the movie is a tonal balancing act that ultimately stays suspended in its own weird, uncanny little universe—an excursion into the friend zone as a twilight zone. But it’s also, in the mold of those that came before it, a movie about what it means to do the right thing—the ending of a not so beautiful friendship as its own form of happily ever after.