Where Four Loko Art Thou? A Search for the Last Original Cans of the 2000s’ Most Loved and Loathed Forbidden Alcohol.

Fifteen years after Four Loko’s caffeinated recipe was pulled off shelves, some collectors are still holding on to their stashes—some for profit, some for memories, and some for keeping the YOLO spirit aliveIt started, as so many things do, as a way to be a little less broke.

It was late 2010, and Michael had just graduated from grad school. He temporarily moved back in with his parents in Pennsylvania. He had $400 in his bank account, and he had a plan. This one involved Phish.

Earlier that year, the Food and Drug Administration had issued a sharp rebuke against several manufacturers of drinks that combined high-alcohol malt liquor with caffeine and other additives typically found in energy drinks. The FDA’s highest-profile target was Four Loko, a sugary-sweet, high-caf, low-cost concoction that had gained a nickname that was equal parts derisive and honorific among the predominantly younger crowd that consumed it: blackout in a can. Within weeks, the drink was pulled from shelves across the country, to be replaced eventually by a new, caffeine-free iteration.

Michael, who requested that his last name not be published, knew Four Loko well. In grad school, he and his friends hadn’t had much in the way of spending money. They found themselves gravitating toward a dingy corner store that trafficked, Michael says, almost entirely in fried chicken, fried clam strips, and myriad malt liquors. A typical night out would start with the crew downing one $2.50 can apiece—which came in at a whopping 32-and-a-half ounces, bigger than a traditional tallboy but just under the heavyweight 40—and then heading out to the bars.

“We’d drink it because it was the perfect pregaming thing,” he says. “When you get to the bar you’re pretty drunk and you’re amped up and ready to have a great time all night.”

The group was emphatically not in it for flavor, which for Four Loko ran the gamut from a vaguely medicinal grape to an almost violently neon blue raspberry; drinkers were as likely to describe flavors by their color as they were by the fruits for which they were named. “It tasted like crap,” Michael says. “If you drank more than two it was terrible, but as long as you could thread that needle, it was ideal.” Cheap, energizing, and boozy enough to reliably launch a big night turned out to be a value proposition that interested many.

Then came the crackdown. At his parents’ house, an unemployed Michael consulted his meager life savings and dreamed of more. “I called around to all the beer distributors in Pennsylvania,” Michael says, asking each whether they still had anything from their last shipment of caffeinated Four Loko. He finally found one with plenty still in stock, but there was a problem: It was a Friday night and the store was in Carlisle, home to Dickinson College and surely plenty of Four Loko–seeking college kids.

The clerk told Michael that they would run out by the end of the night, so Michael did what seemed obvious: He hopped in his 1998 Jeep Wrangler, drove to Carlisle, and bought every can the store had—13 cases of 12 cans apiece, plus a single case of Joose, another caffeinated malt liquor beverage that was also about to be mothballed. The total for the Joose and the 156 cans of Four Loko rang in just under $400, which was hard to not see as fate.

Michael’s plan was simple. Naturally, he would go on tour with Phish—“I’m not a huge Phish fan, but I’m friends with a lot of really big Phish fans,” he says—and sell his newly illicit goods to fans for a tidy markup. If he charged 10 bucks a pop, a successful Phish sojourn could turn his $400 acquisition into a windfall north of $1,000.

He drove back home and started unloading his haul into his parents’ basement. When he laid out his scheme, however, his folks were less than supportive. “My parents were like—[heavy sigh]—Michael, don’t tell us this. You need to get a job.”

We’ll get back to the Phish of it all. But last year, Michael—who did, in fact, get a job, and now works for the state of Maryland—was at his parents’ dining table over the holidays when his phone pinged with a new message. “Hey,” the message read. “I’m having a New Year’s Eve party with some friends and I would love to buy from you. I’m thinking $125, $150 a can?”

Michael passed the offer around to show his family, vindicated at long last. The message hadn’t come out of nowhere, after all. It was in response to something Michael had posted on Reddit: “I think I have the largest collection of original formula Four Loko in the world…”

It’s difficult to overstate the hold that Four Loko had on the collective millennial imagination in the final years of the aughts. Marked by an everyman insouciance, the drink took on something like legendary status for those who tried it, or who simply heard tales about the shenanigans that seemed inherent to consumption of a beverage whose explicit sales pitch was (1) lots of alcohol and (2) lots of caffeine. If your post-recession finances meant that that decade’s spate of highbrow mixologist bars and urban breweries were not on the table, you could find an easy memory, or at least other people’s memories of your memory, in Four Loko.

It was, of course, created by frat boys. A trio of Ohio State friends—Jaisen Freeman, Christopher Hunter, and Jeff Wright, all members of the university’s Kappa Sigma chapter—decided to try their hand at a twist on Red Bull and vodka, the dastardly combo that has become a staple of young-adult evenings out (and which Red Bull’s corporate office decidedly never packaged together). The trio’s first berry-flavored iteration, which debuted in 2005 under the auspices of their fledgling company, Phusion Projects, featured a positively tame 6 percent ABV—a notch over Blue Moon. When that failed to take off, Phusion doubled the alcohol, and slowly the drink known as Four Loko—initially for its defining quartet of caffeine, guarana, taurine, and wormwood—began to get a foothold in markets around the country.

In 2009, it blasted into the mainstream. “If we’re talking revenue: 2008, it was $4.5 million. 2009 was, like, $45 million, and 2010, we were $100 [million], $150-something [million],” Wright told Grub Street in 2018. The product was explicitly marketed toward younger drinkers—the target market was 21- to 27-year-olds, Hunter said in 2007, and the company soon sponsored the aggressively collegiate World Series of Beer Pong.

Yet even as Four Loko broke through, its recipe was already under fire. The FDA sent a letter to Phusion and 29 other manufacturers in late 2009 demanding proof that adding caffeine to alcohol products was safe. The medical establishment’s opinion (and now Four Loko’s own; its website says that caffeine, guarana, and taurine are “potential health dangers”) was a fairly resounding “no,” and a spate of tragedies involving young people soon followed the drink’s booming popularity. Stories of alcohol poisoning and fatal car wrecks in which Four Loko was fingered as a contributing factor abounded. Incidents at college campuses were so pervasive that many institutions banned the drink. In New York, Brooklyn assemblyman Félix Ortiz staged a widely publicized stunt with a local NBC affiliate in which he drank two-and-a-half cans over the course of an hour as a doctor monitored his rising pulse and blood pressure until Ortiz ultimately threw up off camera.

With an imminent FDA ban all but certain, Four Loko officially ditched caffeine as an ingredient in November 2010, with much fanfare around some wholesalers shipping their remaining, unsellable caffeinated product to a facility that would turn it into fuel. But even that didn’t cool the heat entirely: By 2011, the FTC also had Four Loko in its crosshairs, stipulating in an agreement with Phusion Projects that 12 percent ABV, 23.5-ounce cans—the standard iteration of the original drink—would need to feature language cautioning drinkers that the beverage “has as much alcohol as 4.5 regular (12 oz. 5% alc/vol) beers.” The days of the Four Loko Wild West were done.

Did the universal opprobrium by well-meaning, reasonable adults heighten the drink’s appeal to the generation just leaving school? Perhaps. What is certain, however, is that Michael, with his dreams of a Loko Phish tour, was far from alone. As bans spread and the FDA’s condemnation loomed, many stocked up however they could. Cans swiftly became white-hot commodities for Four Loko faithful, and platforms like Craigslist and eBay lit up with black-market listings for the drink with dramatically higher prices than the original retail ask—leading to more than a few arrests as police attempted to rein in the surging unlicensed market.

The Columbus Dispatch interviewed Bryan Crane, whom the paper dubbed the “king of the Four Loko black market in the Midwest,” who boasted of inheriting 1,500 cans courtesy of an uncle’s convenience store. “I drank one, and it was the worst experience I think I’ve ever had,” Crane said. He planned to charge $20 per can by the end of the month.

In New York City, a man named Phil was charging five bucks each within weeks of Phusion discontinuing caffeine in the drink. “That stuff is really a menace,” he told the New York Daily News. “Everything’s going fine and then it hits you like a ton of bricks and you don’t remember the rest of the night.” He told the paper that he planned to spend any profit “to replace the shoes that I threw up on.”

Then there’s James. A native of the Seattle area, he took the disappearance of original-recipe Four Loko as a challenge. James, who also requested that his last name not be published, is something of a unicorn: He really, really liked Four Loko. He and his friends would slip down to a gas station to “pre-funk,” as they say in that corner of the country. They were particularly eager for a boost of caffeine along with their alcohol. “A lot of the bars wouldn’t have Red Bull or an energy drink to mix,” James, 37, says. Some establishments offered to brew coffee and add whiskey. “I’m like, I don’t want an Irish coffee.”

So James and friends took matters into their own hands. “We would try different things, like Joose and Mike’s Harder and stuff like that—but you just get gut rot,” James says. “Then we saw these things called Four Loko and I was like, not only is that a good bang for your buck, but there are some decent flavors.”

It quickly became an after-hours go-to—“Is this a lemon-lime Loko night? Is this an orange Loko night?” he remembers being the discussion—so its imminent disappearance was a threat. James responded by making a tour of local gas stations in search of remaining caffeinated Four Loko stock. He found he was often able to convince cashiers, particularly at independent establishments, to take him to the back where he would buy whatever Loko they had left in cash—especially if he waited till no one else was in the store.

“One guy was like, ‘Are you a cop?’ I was like, ‘Would a cop buy Four Lokos? I’m 21. I want this junk that you don’t want, so.’”

By the time he stopped, James had amassed 60 12-can cases of Four Loko, which he and his friends happily broke into long after the drink stopped being publicly available. The Halloween after original-recipe Four Loko was pulled, James borrowed the army uniform of his father, who served in Vietnam, carefully painting his face in the neon green and yellow camouflage pattern that adorned lemon-lime Loko cans and constructing a grenade belt that held full cans in lieu of explosives. “People were losing their shit,” James says. “I started giving a few away. And it was a hit. It was amazing.”

From his original stockpile, James has just six cans left, each in a different one of the original flavors, which he keeps in a six-pack wine bag in his garage; years have passed since he’s opened any. “I probably should just get rid of them now,” he says. But every once in a while, someone makes him an offer—most recently $450 for the whole bunch. Another offered him $100 for a single can, which the would-be buyer said he planned to drink. “I’m like, ‘You might die. I don’t think that’s a good idea. I don’t know if this is drinkable.’ But if someone were to offer me the right price for all of them? I just want them gone.”

Steve Burke is the rare Four Loko collector whose trophy didn’t come from a ban-era panic buy: He simply bought a case in 2006, opened precisely one, took a sip, and thought, “Wow, this is the worst thing I’ve ever had in my entire life,” Burke says.

Ultimately, Burke, who lives in New York City, tucked the remaining 11 cans into a storage unit along with similarly polarizing youthful drinks like Goldschläger and let them be. This past summer, as he prepared to move in with his fiancée, he decided he’d had enough of storing the almost 20-year-old libations and made a half-hearted attempt to sell the lot. When that failed—some cans had sprung leaks and others were visibly rusting—he opted for donation.

There’s a shelter close to his office, he says, that often attracts a jovial crowd who hang out on the sidewalk, talking and sometimes drinking. Burke decided to offer them the lot gratis—save a single can of Four Loko that he’s kept for posterity. “I was like, I’ll just tell them the truth. So I went up to them, and I brought the other various liquors that felt like a good purchase when you’re 21, and I was like, ‘Hey guys, I got these. They’re actually the original ones. Do you guys want this?’”

Burke says that he stressed that it was old—not fancy wine old, just old. “‘I don’t even know if it's good,’” he says he cautioned. “I was like, ‘I’d be cautious. Maybe it’s poison now. It was poison in 2006 so it’s definitely poison now.’ And they laughed and were like, ‘Oh, we’ll take it.’”

It was a hot day in July. Smash cut to later that afternoon, when Burke says that he next checked in on the group, only to find that they had broken out into an all-out brawl. “The cops showed up,” Burke says. “Guys got beat up. People got arrested.

“I was like, well, I guess it’s still good, because that’s what usually happened with Four Loko in 2006.”

It has now been nearly 15 years since the original recipe of Four Loko was discontinued. In the years since, the drink’s chaotic heyday has become a calling card for the millennial generation. Yes, it’s possible to reverse-engineer a similarly caffeinated, bad-for-health brew even now. But there was something special about the window in which a patently bad idea seemed like, and sometimes was, a very good one.

Ultimately, Michael put his Phish plans on hold. He moved out of his parents’ house, but for a time continued to store his hoard in their basement. Sometime later, his dad called him, threatening to chuck his precious $400 almost-payday into the trash.

“I was like, ‘Dad, if you throw that away, I will freaking disown you. That stuff is priceless,’” Michael says. His dad insisted it was junk, so he made his final plea. “‘Listen, Dad, if you wanted to buy a 100-year-old Burgundy, you could buy that tomorrow. It would cost a lot of money, but if that were a goal of yours, you could call someone and within a few days, you would have it. A market for that exists—there are sellers and buyers, and you could have it by the end of the week in your hands. But if you want an original can of Four Loko, there’s no place you can get it. Unless you're like a weirdo like me.’” His dad relented.

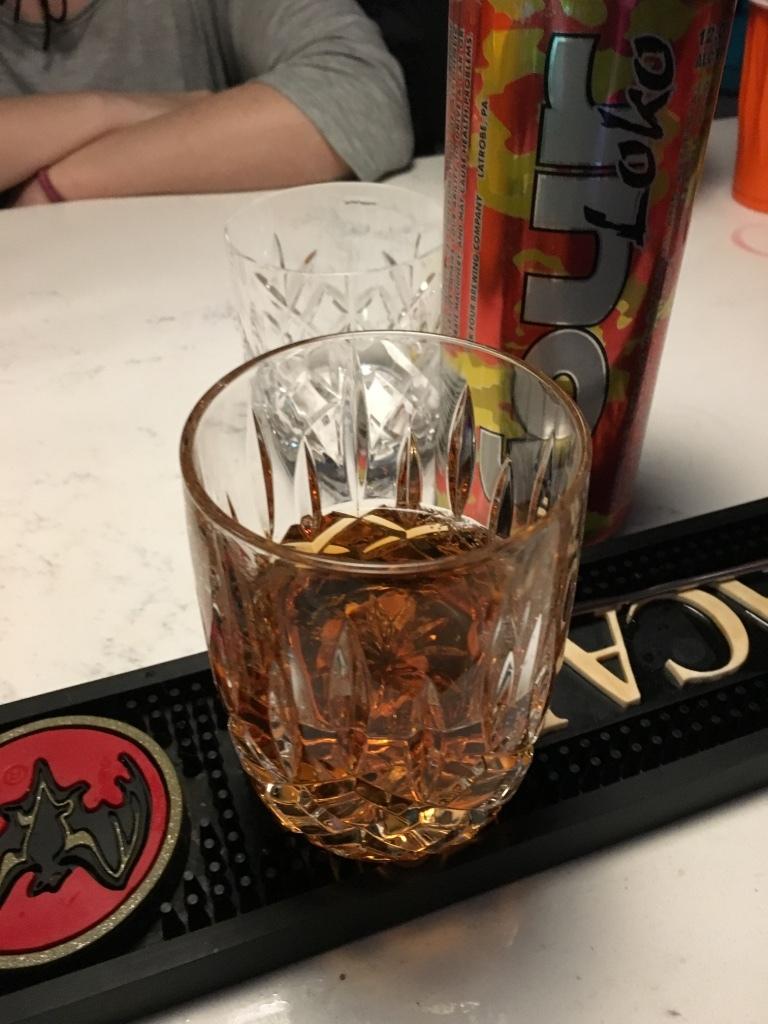

Over the years, Michael has gradually chipped away at his collection, which for many years was kept in a non-climate-controlled storage locker on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Some cans have, like Burke’s, sprung leaks; Michael now has 51 in all, in a variety of flavors, each in reasonably good condition and stored safely in a cabinet in his home. Every so often, he’ll take a single can to a party, where samplings are doled out in cocktail glasses and served “like a fine whiskey,” he says. This has led to a surprise: Many of the Lokos have turned very different colors than they were when freshly released. Blue raspberry, he says, is now the shade of “green cough syrup,” while fruit punch has faded to a warm amber.

That holiday offer from a stranger last year was not an anomaly: Michael’s post on Reddit about his Four Loko arsenal has drawn numerous offers to purchase cans; when I reached out to him, he told me I was not even the first to contact him that day. But mostly he hasn’t been tempted.

“Four Loko fulfilled a very specific purpose at a very specific time in my life, and for the most part that time is gone,” Michael says. “I no longer move into a new home every few years and I have gray hair, a stable career, and a house. I say I still like to party, but what used to be a typical Friday night with friends is now maybe a twice-annual occurrence which was likely planned for weeks or months in advance. My life is far from boring, but 27-year-old me would run circles around 42-year-old me. When faced with the question ‘Am I turning into a boring old person?,’ the stash of 51 cans of OG Four Lokos is one of the few tangible things I can point at and think ‘No fucking way.’”

Michael just might be right that he possesses the largest collection of intact aughts Four Loko. But there are many more people out there with a solitary can that has been collecting dust all these years.

In my search for the last vestiges of original-recipe Four Loko, I met Matt Wilcox, a 40-year-old dad of two who lives in San Jose. He was in his early 20s when Four Loko swept the nation. “We used to have one, and that was good enough to get us flying high and lubed up and eyes all bug-eyed from the caffeine and out the door,” Wilcox says of his friend group’s pregame of choice in those early days of disposable income.

When the crackdown came, his friends were prepared and promptly bought all the cases they could find. For months, the group gradually worked their way through the haul. “It was treated like, ‘Hey, this is the one night a month we’re gonna Four Loko it up,’” Wilcox said. “They slowly bled themselves dry.”

But not before Wilcox secured his prize: a single can of aughts-vintage, caffeinated cherry flavor. He stashed it in his fridge for safekeeping. “I held onto it, thinking that it was going to be my form of champagne,” he says.

Wilcox brought it along with him as he moved from place to place, and tucked it into the refrigerator when he moved in with his now-wife. But special occasions came and went and none quite seemed like the appropriate venue for Four Loko. A native of Arizona, he hoped a sporting victory might be the one; alas, the time was never right. Life milestones, too, didn’t really jell with the Loko days of yore: “Cracking it on my wedding night was not on the list of things to do,” he says. Nor was diving into it in the hospital after the births of his children.

“Fifteen years pass, and it becomes more and more daunting to stare at that thing in the bottom of my fridge,” Wilcox says. He considered selling the can, but no one bit; by the time we spoke, he said he was ready to be rid of it and finally reclaim that long-taken spot of refrigerator space. Jokingly—I thought—Wilcox even offered to mail me the can.

It just so happens that I’m due at a friend’s bachelor party on the West Coast next week. After we spoke, I wrote Wilcox a note: Was he really serious about casting off his nearly 15-year-old Loko? Could he imagine a world in which the groom-to-be and our friends might spice up a weekend of fly fishing and golf with a sampling of some of the last original Four Loko in the land?

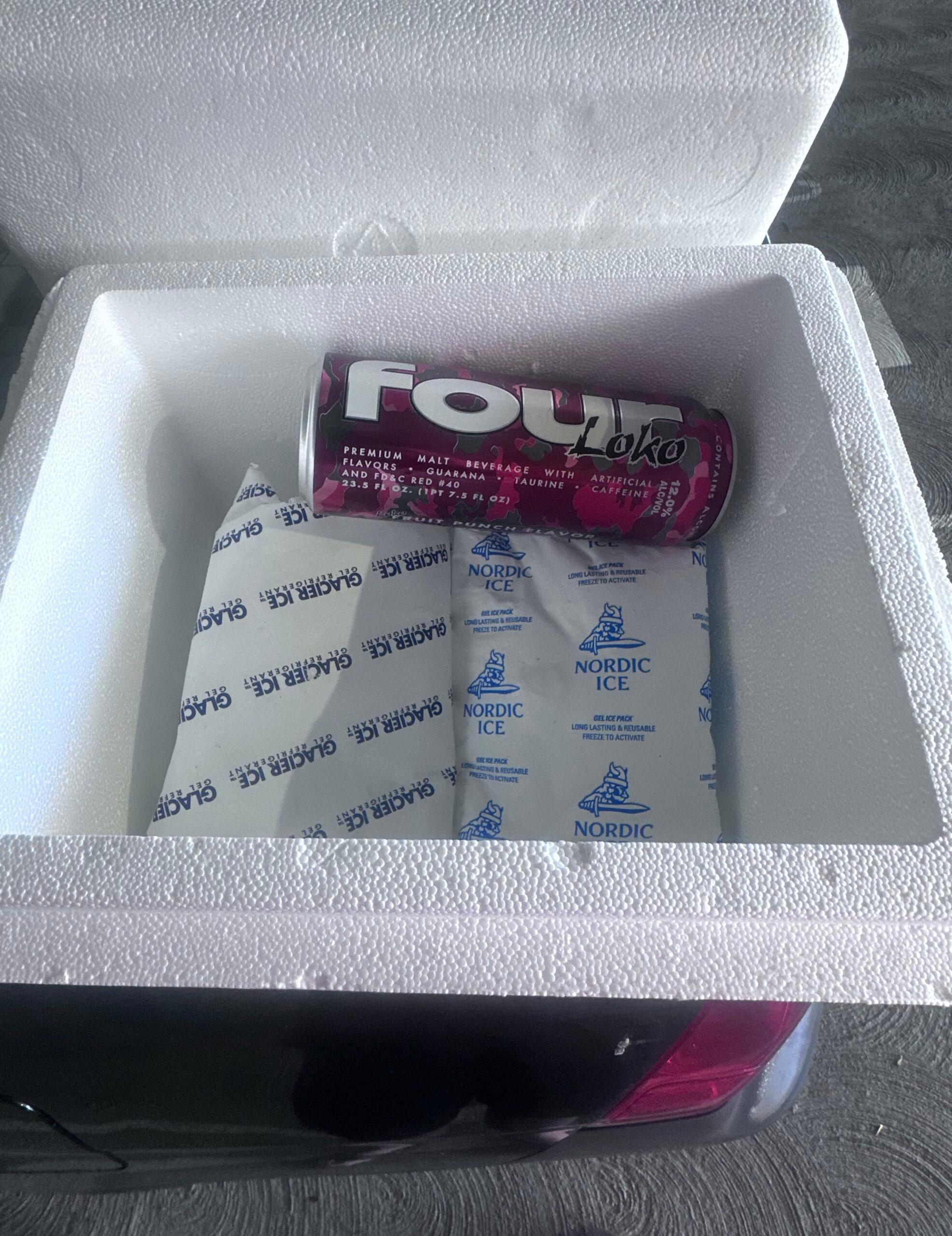

Wilcox was indeed serious. The next day, another friend in the Bay Area met him in a parking garage near Wilcox’s office at a biopharmaceutical company and secured the can. My friend brought along a cooler and a pile of ice packs, which he joked would be fit to transport a stolen kidney.

At press time, Wilcox’s gifted Four Loko was awaiting one last journey. Its final voyage will take it to Oregon, where if all goes well, your writer, a none-the-wiser betrothed pal, and a smattering of friends will be sampling a vintage Loko this time next week.

If you don’t hear from me again, well—you’ll know that Four Loko still packs a punch.