It doesn’t feel like a funeral.

On the third floor of ESPN’s South Street Seaport studios in New York, in the lobby of a mostly empty newsroom, Tony Reali is all smiles. Alongside his wife, Samiya, and his three young children—Francesca, Enzo, and Antonella—he greets close friends and extended family like a public address announcer, reciting their names and brief backstories as they walk through the door. Others soon follow. There’s his trainer, who turned Reali from a CrossFit fanatic into a slow, functional mover. There’s his younger brother, who sports the New York accent that Reali learned to refine at the start of his career. There’s Dan Le Batard and Pablo Torre, former ESPN employees eager to bear witness to their ex-colleague’s final salute. They arrive about 90 minutes before showtime, but Reali is happy to provide hospitality, handing out water bottles and directing the crowd down the hallway to trays of pizza and chicken wings.

“You guys want a tour?” he asks in his signature booming voice.

Over the past few weeks—well, really since March 4, when ESPN officially announced his show’s cancellation—Reali has been concocting, rehearsing, and refining the way he wants to say goodbye to Around the Horn, the weekday sports talk and game show that he hosted for the vast majority of its 23-year, 4,953-episode run. Not long after taking over for Max Kellerman in 2004, he turned the initial concept—four rotating beat writers from across the country are scored on their arguments about the day’s biggest sports headlines—into a ratings hit and a pre–Pardon the Interruption staple of ESPN’s “Happy Hour” programming. But after reports of the show’s demise grew last year, the network set May 23 as the last airdate, sunsetting an institution without explanation. Reali struggled with the news. He knew ratings had stayed consistent. He didn’t think the show’s quality had regressed. Yet now he had 10 weeks to program and process the end of a 21-year chapter of his life. “I've done a lot of work on myself through the years. I feel like I know what this industry is, and I know what our job is,” Reali says. “Why do shows end? Because everything has to end.”

When I first met Reali at the beginning of May, he was already hatching ideas for this final episode. He knew he wanted to preside over the longest-tenured panelists (Woody Paige, Bob Ryan, Bill Plaschke, J.A. Adande, and several more) as they debated superlatives from the Around the Horn era: the true GOAT (LeBron? Tiger?) and the best sports story line. He wanted to finally explain his seemingly arbitrary scoring system and highlight the behind-the-scenes work of his D.C.-based producers. And he wanted to start the show by replicating the one-shot “Copacabana” sequence from Goodfellas, his favorite movie, complete with fake $100 bills; a special appearance by Ellie the Elephant, his kids’ favorite mascot; and a dance party in the center of the studio.

In other words, this would be a very Tony Reali episode. And why not? Near the start of its impressive lifespan, and even as it evolved into a less aggressive version of itself, Around the Horn leaned into its encyclopedic, exuberant host to establish an energized, smart, and freewheeling tone, one that quickly informed the personality-driven debate-show ecosystem of ESPN that has now swallowed Around the Horn whole. “There was no show without Tony Reali,” says Jackie MacMullan, who joined ATH as a panelist when it debuted in 2002. “I don't think people realize how deftly he managed some massive egos to make everybody feel wanted and loved and important on that show. He was the one thread, all the way through, that made that show special. Made it a family.”

This is the kind of memory that makes today emotional, but it’s not time to get sentimental yet. Reali still has one more show. Like everyone who works on Around the Horn, he knows that he won’t get closure from the people that have kept him employed for the majority of his adult life. Over the next couple of hours, he and his staff will have to manufacture it themselves.

Throughout the past several days, the greener panelists of Around the Horn had spent their final “Face Time” segments sharing how the show propelled their television careers, gave their voices a platform, and supplied them with a lifelong community. This afternoon, the OGs are ready with their own goodbyes. After pretaping two takes of his Goodfellas tribute—“Scorsese did eight takes!” Reali justifies—to ensure his kids brought the right amount of enthusiasm, Reali moves to a familiar position behind the control panel, looks at a screen filled with his old friends, and offers up some reflections.

“You helped me grow as a man,” he tells Plaschke.

“We don’t make it to Episodes 2, 3, or 4 without you,” he tells Ryan.

“You’re my best friend,” he tells Adande, prompting the Chicago-based journalism professor to reach for his tissues.

“You had the courage to write about depression and model a way to live a life,” he tells Paige.

These daily preshow commentaries are standard practice for Reali, but they carry extra weight today. He shakes out the feelings and switches into hosting mode: “Let’s do a show!”

When Around the Horn debuted on November 4, 2002, columnists held a prominent place in the sports media landscape. Their weekly takes could sway a fan base, and their authoritative stature made them obvious candidates for television. That was the impetus for creator Bill Wolff’s experimental game show, which provided viewers with a daily “cheat code to hear all their thoughts,” MacMullan says, and injected the political roundtable vibe of The Sports Reporters with more energy—points, mute buttons, argumentative chaos and criticism, distilled into 30-second sound bites. Its frenzied, rambunctious nature emanated from host Max Kellerman, who began each episode with the same declarative monologue about the takes he was ready to test-drive with each day’s panelists: “These four things I know to be true …”

The show was loud, abrasive, theatrical, and unlike anything in sports media. It also pushed back against TV’s perceived New York bias, celebrating the regional perspectives of writers in Boston, Chicago, Denver, Miami, and Los Angeles by leaning on each panelist’s local insights and locker room access. Coordinating producer Aaron Solomon anticipated a short shelf life for the show—it was ripped by critics and struggled in the ratings, and even though it featured MacMullan, Adande, and Kevin Blackistone, “for the most part, it was crotchety white guys,” Solomon says.

Mostly, it was a vanity project for Kellerman, an opportunity for him to editorialize on trending topics and have control over a rogues’ gallery of hothead journalists. As the only woman on the show, MacMullan didn’t mind Kellerman’s brazen shtick, but she wasn’t sure a screaming, masculine version of Hollywood Squares did her any favors. Others agreed. She remembers covering a Spurs game as a young NBA reporter when Gregg Popovich approached her. He’d loved watching her on The Sports Reporters but had stern advice regarding her Around the Horn appearances. “I don’t think you should do that other show,” he told her. “It's not what you stand for.” MacMullan respected his opinion and ultimately stepped away for a few months. “The silliness, the shouting over each other—that was hard for me,” she says.

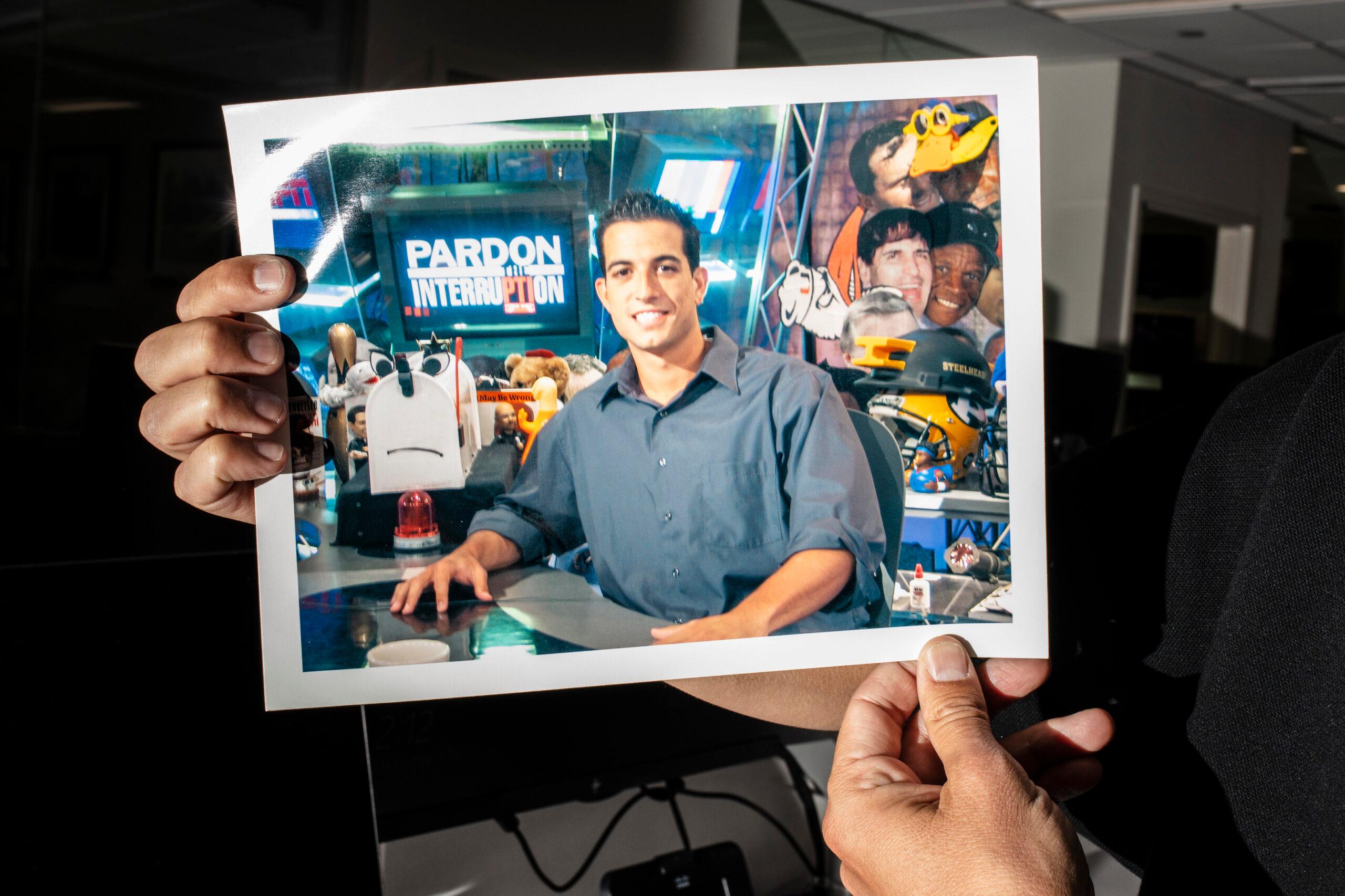

Then, on February 1, 2004, during the now-infamous Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime show, Around the Horn entered into a new era: In the middle of contract negotiations with Kellerman, ESPN called Reali and asked him to host Around the Horn the next day. At that point, the Fordham University graduate had spent a couple of years as a researcher for Pardon the Interruption, where he’d earned the moniker “Stat Boy” and become a regular at the end of the show, fact-checking Tony Kornheiser and Michael Wilbon. After that call, he started to fill in for Kellerman—and occasionally played panelist—across the studio when necessary. Still, the gig felt temporary, at least until Kellerman left for his own Fox Sports show.

A telegenic and enthusiastic but ultimately inexperienced 25-year-old, Reali continued playing quarterback, assuming ESPN would eventually tap a more prominent voice—“Stuart Scott?” Reali thought—to replace him. Instead, the network stuck with its young gun, impressed by his natural chemistry with panelists and otherworldly sports IQ. “It was kind of a natural fit,” Solomon says. “He just worked so well in that position that he didn’t really give it up, and nobody really objected to him being there.”

The first year was tough. Within six weeks of Kellerman’s departure in 2004, creator Wolff, producer Brad Como, and director Howie Lutt all left the show. But the mass exodus gave Reali the chance to mold Around the Horn in his own exuberant and compassionate form. Over the next year, he adopted a deferential approach, taking the spotlight off himself to highlight the award-winning columnists and reporters streaming in from the country’s most prestigious newsrooms. “I always want to give credit and acknowledge everyone who’s worked on the show,” he says. That meant tweaking and eliminating a few things—namely, Kellerman’s opening statement. In its place? “You’re looking at four sportswriters who are …” The switch changed the dynamic and helped Reali embrace the show’s gamified qualities. “We’re a show with a scoring system,” he remembers thinking. “That’s what differentiates us. We’ve got to give you that every day, no matter what.” MacMullan felt things changing with him. “It became very funny, but we were still covering topics that mattered,” she says. “I just thought we steered the show in a really great direction.”

As he logged more episodes, Reali gained confidence—and the reins of the show. He points to an episode he hosted three months into the job, during the 2004 NBA playoffs. Reali wanted to cover Kobe Bryant’s sexual assault case but struggled with how to present such a sensitive subject. “There were stories I wanted to do where it felt odd to give a ding-ding-ding,” he says. “That’s a huge story, and I’m on a game show scoring people’s arguments about it? That didn’t feel right.” So on that day in May, Reali decided not to score the segment at all.

“Tony started getting better, and the show started getting better, and we started seeing some results,” Solomon says. “He just really grew into the position.”

By the first commercial break of the final taping, Reali is in his element. He’s just awarded Woody Paige 12 extra wins to push his career total to an even 700, prompting the former Denver Post scribe to douse himself in Champagne—one last fitting gag for the show’s longest-tenured, least serious contestant. As the next quartet of veteran panelists satellites into the studio, Reali pivots his attention to the crowd. It’s one of the few times he’s gotten to perform in front of a live studio audience, and he’s happy to cosplay as a warm-up act. He announces more friends who have belatedly entered the studio. He offers up more selfies by the desk. And then, on a dime, he changes direction once producer Josh Bard alerts him to the teleprompter and readies the tape.

At this point, Reali can feel this show’s rhythms in his bones—he knows when he can take a break, scroll through his phone, look over a script, or engage backstage observers. Since taking over for Kellerman, Reali and the production staff have maintained the same daily schedule to bring the show to life. It has always started inside a shared document. After catching up on the previous night’s score and stories, Solomon and Bard would sketch out a list of potential topics and order them into segments. Then, around 10 a.m. ET, that day’s panelists would convene on a conference call to discuss each topic. “We’d get their opinions on things, and sometimes they’d be enthusiastic about certain topics and sometimes they’d be like, ‘Oh, we’re talking about LeBron again …’” Solomon says. “You can tell their enthusiasm.”

This procedure has changed slightly over the past few decades, namely when Reali moved from D.C. to New York in 2014 to pursue a side gig with Good Morning America. “The biggest thing we lost was Tony's energy,” Bard says. “It is the best. It is contagious. It's not that we don't have great office chemistry, but it just takes away from it. You're losing a real strong, positive voice.” The rundown, filled with 15 pages of associate producer and researcher Caroline Willett’s nutrient-filled notes, also turned into more of a living, breathing document when social media became ubiquitous, forcing producers to adapt when news broke close to the filming schedule. “We’d kind of keep topics in, move them up, or move them out based on what Tony says, too,” Solomon says. “It's always been our kind of thinking that the panelists have to be excited about it. Tony has to be excited about it. If not, the show doesn't work.”

The structure and preparation remained the same, but the show became current and relevant. According to Reali, the biggest evolution occurred when he began scouting for new talent. “The show was already based on variety and diversity—of time zones, of voices—but I said, ‘Let’s apply that to everything,’” Reali says. This wasn’t a unilateral decision. Reali knew that clearing new panelists meant less time for his regular rotating cast. “When I said, ‘There’s this reporter out of Chicago, she works in radio—Sarah Spain. That’s a voice we need,’ they were open to it,” he says. “But that was growth. That was important. Because now we could have any conversation at any moment.”

Mostly, Reali recognized the shift in how a national audience was consuming sports, that “the regional thing, that foundation of the show, eventually didn’t matter as much,” he says. “So we made an active decision: Don’t lean on time zones anymore. Lean on something else—different perspectives, different genders. I never wanted to do a show that was just four white guys.” That started with journalists who didn’t always have strict newspaper backgrounds, such as Bomani Jones, Pablo Torre, Clinton Yates, and later Spain, Mina Kimes, and Courtney Cronin. “Seeing myself in one of the boxes, just like I had seen Jackie MacMullin and Woody Paige and all the people years before me, it was like, ‘Oh my God,’” Spain says. “Now people will see me in that little box the way I saw all the people in those boxes.”

Frank Isola, who joined the show in 2013 and took on a New York homer persona, remembers his favorite debates on the show centering on women’s sports. When the U.S. women’s soccer team ran up the score against Thailand in the 2019 World Cup, Isola thought the team’s behavior after each goal was “embarrassing” and “out of line,” but he loved that he and Spain could argue the opposing sides. “I just thought it was good because if you want to [highlight] women's sports, this is the shit you got to talk about,” he says. “But also, Around the Horn was, in some ways, the only place for those kinds of conversations to happen in a way that's not annoying and egotistical and showboaty.”

The show kept adapting. It changed its theme song and graphics and eventually switched its presentation to augmented reality, allowing Reali to have a more dynamic camera presence and roam around the studio. It also remained dedicated to fun—there were always awkward freeze-frames and Woody’s chalkboard, but the show’s panelists also celebrated Halloween with extreme commitment, and Reali conceived of new ways to do the show, like when he reverse engineered it and ran the order backward on April Fools’ Day. “So many people are so serious about their takes and their opinions,” Bard says. “This is supposed to be fun, right? This is sports.”

Around the Horn’s unpredictable nature helped bring out its humor, but it also allowed for harder conversations. Willett, who ran the show’s social media channels, still gets notifications from the 2018 video clip of Reali sharing a tribute to his son, Amadeo, Enzo’s twin, who was stillborn. Reali has worn black every day since to honor his memory. “That's exhibit A of Tony wearing his heart on his sleeve and people receiving it well,” Willett says. The instant reaction convinced the producers that the show could let Reali and other panelists speak about personal causes, reflect on loss or depression, or pay tribute to people who made a difference in their lives. “I've worked with a lot of talent in television,” Solomon says. “There's nobody with a bigger personality and a bigger heart than Tony Reali.”

Reali noticed this vulnerability and empathy within himself as a kid. At Fordham, ahead of Global Outreach service trips, he was required to send letters to friends and family members expressing the ways in which they’d helped him grow. But even after completing each retreat, he continued letter writing as a regular practice. “I would crave emotional connection,” he says. “This is me as a 20-year-old, you know? A little bit of a different cat, especially for a guy.” That continued throughout his career in various ways. As is now Reali legend, the host made a habit of calling and texting panelists ahead of their first show, hyping them up and making sure they were adequately prepared. Torre still has Reali’s introductory voicemail on his phone. Spain remembers him answering all her questions before her debut. “Tony really fought for me, which was awesome,” Spain says.

“I really put the show in a box a little bit too much,” Reali says, looking back. “This is a silly game show. This is a show with a mute button. Maybe I condescended [to] the show in my own head as a way to lower expectations over what I could do as a host.” But then he had a light bulb moment: He had to be himself. “Your emotions are your superpower,” he says. “You keep it real. I'll keep it Reali.”

The last episode of Around the Horn is nearing its end. Tim Cowlishaw, Blackistone, Isola, and MacMullan share their final arguments and some memories, throwing in a few sly barbs for network brass and baring their souls about how this show changed them. Reali is left speechless. “You’ve muted me,” he says slyly.

Reali has felt that way a lot over this past week. The tribute that keeps recurring is an appreciation for the way Around the Horn springboarded each panelist’s television career and stature as a journalist. The show’s saturation in locker rooms and clubhouses made panelists more recognizable to athletes; the daily show notes aided their columns; and its competitive, rapid-fire nature, its demand for energy and charisma and cleverness, proved that they could hang on live television. “The hardest part of all about Around the Horn was you had to know everything,” MacMullan says. “In my mind, if I wasn't up to date on everything, I wasn't doing my job. I didn't belong on the show.”

The more fresh faces and voices filled the air, the more it became a launching pad for new and existing ESPN programs. Not long after starting their runs on the show, Torre and Jones teamed up for High Noon, Kimes graduated to NFL Live, and Emily Kaplan and Monica McNutt got more broadcast opportunities and morning show appearances.

Aware that “legacy” is one of several sports terms that Reali has banned from the show in recent years—the list also includes “narrative,” “problematic,” and “elite”—Solomon considers Around the Horn’s talent cultivation as “legacy-like” and one of its primary achievements. Of course, it also helped lay the groundwork for the network’s eventual “embrace debate” era. A few years after Reali began hosting, the network debuted—and then got consumed by—First Take, a debate show that felt akin to ATH’s early, rowdier years, when Al Michaels called the panelists “gas bags on parade.” “We kind of started a genre of television debate,” Solomon says. “A lot of shows spawned off of us.”

Yet the longer Around the Horn ran, the further it strayed from that loud, theatrical version of itself. “We really tried to be a little bit more thoughtful, tried to be a little smarter, tried to have a bigger diversity of opinions,” Bard says. “We really tried to get away from this hot-take culture. We were definitely putting out hot takes every now and then and enjoying them. But we tried to get away from that being sort of the currency.”

Which brings up a more important question: What do we lose when we lose Around the Horn?

The simple though hardly groundbreaking answer might be: journalistic perspective. Even as it shifted away from highlighting specific regional perspectives, the show’s basic conceit—that experienced beat writers who’d spent the previous night at a game, in a clubhouse, talking to league officials, would debate from all across the country with various points of view—remained, a feature that now seems downright old school. “You're reminded that there are people who have to show up at practice every day, travel with the team, get the quotes, have the relationships, earn the trust,” Spain says. “I just think it matters when someone that actually works with the team says something about them. It really feels meaningful, compared to just another person on the internet that has never met any of the people they're talking about.”

Reali appreciates this distinction. Consider that his entire job before Around the Horn was making sure Kornheiser and Wilbon shared accurate information and that he knew exactly when and how they’d made a mistake in their arguments. “I was a stat boy. I never wanted wrong information on PTI or Horn without a citation or a correction,” he says. “Caroline knows how important that is to me. I will make sure we're all right during the commercial break and get prepared to do a rejoinder. I value getting stuff right and citing sources. I'm not a journalist, [but] I work with journalists every day, and I'm going to uphold their standards.”

At a time when legacy media companies and newspapers frequently lay off veteran journalists, player-driven podcasts have saturated the media landscape, and ESPN invests more in personalities like Stephen A. Smith and Pat McAfee, Around the Horn has looked like one of the last institutions to champion nuanced, informed opinions and original reporting. “There comes a time where there’s not enough journalism,” Isola says. “The former athlete has really replaced the columnists and the newspaper people. I think we're at the point where the players get way too much of a pass. And it's more about killing the coach, killing the front office, killing the fans, and killing the media for the way that they talk about the players.”

Cowlishaw also laments these points in his parting shot. Then Reali makes his last paper toss to the camera. Later, a friend asks whether he can autograph the crumpled souvenir. He’s done this for fans on several occasions, and the request gives him another opportunity to narrate this monumental day to the crowd. Typically, he says, the paper is an old show rundown, but this one’s a call sheet for First Take. Reali can only laugh at the irony. He signs his name on it and then cracks a joke: “We’ve been eaten up by First Take!” he yells. “And you can put that on the record.”

Every day, for as long as he can remember, Reali has started the morning relatively the same way. At the kitchen table of his Brooklyn home, he digs into the rundown, pours a cup of coffee at 7:15 a.m. (“I didn't drink coffee, nor did I need coffee, until the pandemic,” he says), and makes his kids breakfast. Later, he hits the gym, then logs onto the Zoom call with all eight panelists. Around noon, he hops on a ferry and enjoys the four-minute ride across the East River. “I'm a seafaring people, just like my ancestors who came over from the boot,” he says. “I get seasick, but not on that boat.” He then makes the five-minute walk to the studio at Pier 17, not far from where his grandfathers worked unloading bananas for a brief period of time.

But starting this week, for the first time in his adult life, Reali doesn’t have a script to write. He doesn’t have a short commute. He doesn’t have a show to host.

The question of why this happened has been the focus of every story about Around the Horn over the past few weeks, as speculation fills a void left by ESPN’s refusal to share its reasoning for the cancellation. Maybe the network wanted to shift direction with its new streaming service. Maybe it would rather invest money in shows featuring former athletes. Maybe ATH got too “woke” and “political.” Maybe it just didn’t generate buzz and grab enough attention. “Some of the loudest voices on ESPN seem to love that hype and seem to love getting themselves into the story,” Bard says. “We have tried not to be doing that. We tried to talk about the story without becoming the story.”

As previously reported, there are only two certainties right now: Ratings were not an issue, and SportsCenter will temporarily take the show’s 5 p.m. slot. Of course, Reali knows nothing is promised, especially in television. When Around the Horn entered the sports media ecosystem, it fashioned itself as the brazen disrupter of the staid roundtable. It was nimble and thoughtful enough, however, to escape its burn bright, die fast fate. From there, it established itself in the culture and kept on adapting its 30-minute block. It survived long enough to see the advent of a supercharged hot-take-industrial complex, long enough to see itself get disrupted. Everything has to end.

Still, Reali thought there was more time. “I’ve loved working for this network because we can do amazing things with different people,” he says. “Somebody can be wearing a cowboy hat when the Cowboys lose, and someone else can be pouring out their heart in a show. I think that's important for any network. I thought we served that purpose.”

Maybe the easier, less doom-spelling question is: What’s next for Reali? He’s thought about this for a while. He knew he was probably taking a risk by devoting himself to one show his entire life. He could have started a podcast, embedded himself more in the digital space, or tried to make his four-year stint on Good Morning America work better. “I may have been wrong for some time when I thought, ‘I don't need a podcast. I have an international television show,’” ReaIi says. “I took pride in that, and I carried the weight of that. And that may not have been the best career decision, but it was the right heart decision for me.”

Over the past few months, Reali has taken meetings with NFL Network and NBC. He’s thought about podcasting. He’s learning about how people build brands, highlighting the work Colin Cowherd has done with The Volume. “You know what I'm the most envious about? Dave Portnoy and pizza,” he says. “How did we not invent this? We're the Italians. I would love to do spaghetti [reviews]. I'm trying to get up to that level where I can think about ownership in that way.” His colleagues also have ideas. Host a game show, NFL RedZone, or Yankee postgame show. Maybe TED Talks? “He’s just so good at motivating people,” Solomon says.

In the final moments of the show, as he explains the scoring system, Reali directs viewers to his YouTube channel, where he promises an aftershow livestream at Meadowlark Studios to interact with his community. That’s ultimately what Reali wants to have—a dedicated space for his people to talk sports, to connect.

As he signs off to silence and then delayed applause, Reali keeps his emotions together. There’s a tendency to call this moment, this ending, “surreal,” he says. But that’s not what this is. This is real. “So much of what we do is habit and routine that we forget when something is truly a real experience,” he says. “I never felt that way about Around the Horn.”