Hosts

About the episode

This is the first episode of a little experiment we’re trying this year, a podcast within a podcast on history that we’re calling, simply enough, Plain History. There are, I am well aware, a great number of history podcasts out there. But one thing I want to do with this show is to pay special attention to how the past worked. In this episode, for example, we’re using the assassination of an American president to consider the practice of medicine in the 19th century.

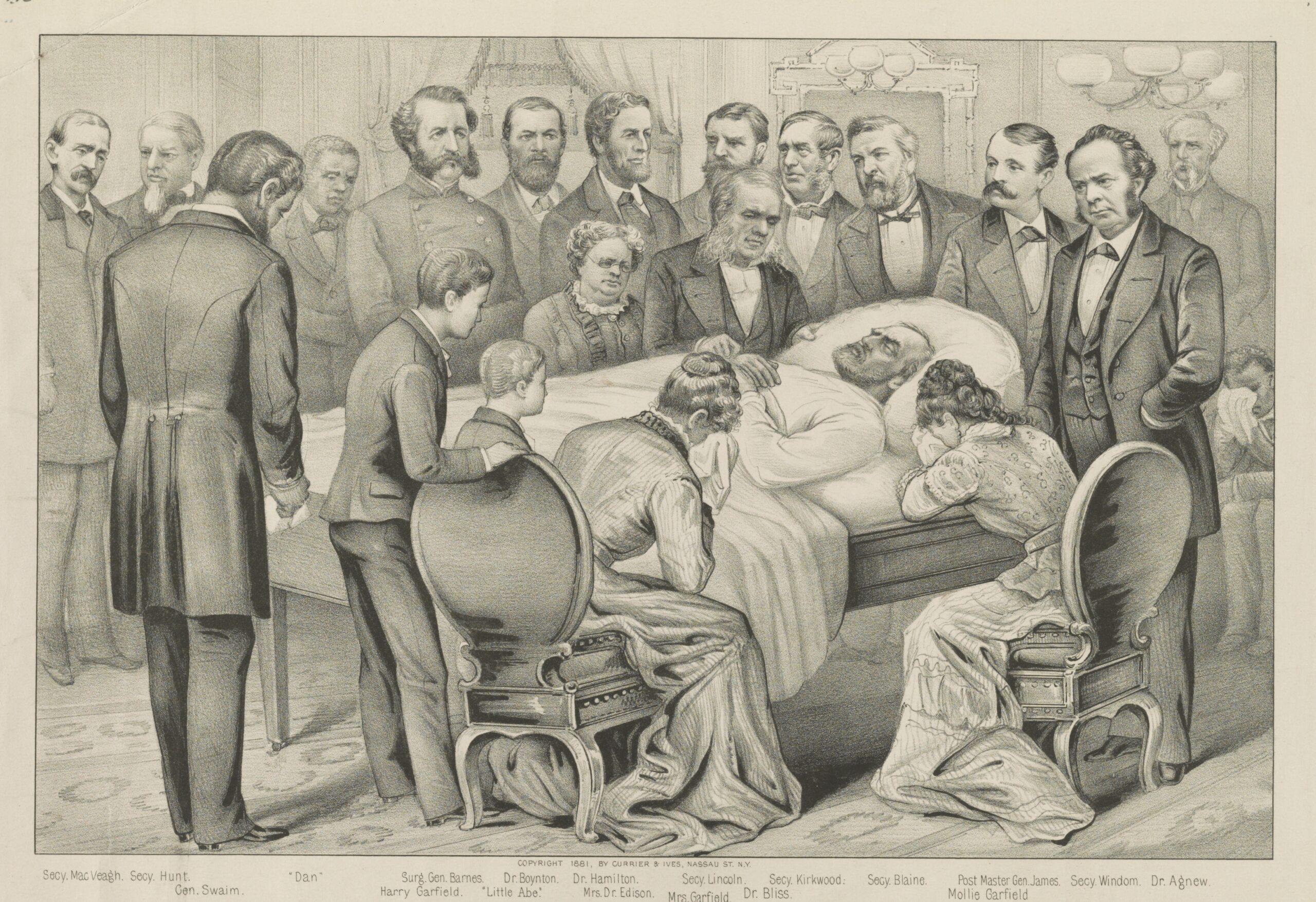

Our subject today is the bestseller Destiny of the Republic by the historian Candice Millard, on the incredible life and absurd and tragic death of President James Garfield.

In the summer of 1876, the United States celebrated its 100th birthday at the U.S. Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Of the millions of people who walked through the grounds, one was Garfield, who attended the centennial with his wife and six children. In four years’ time, he would be elected president at a shocking and chaotic Republican convention. But at the time, he was a 44-year-old congressman known in Washington for being a rags-to-riches genius.

Garfield was a perfect match for the centennial grounds, which were themselves a gaudy showcase of genius. In Machinery Hall, visitors could pay for a machine to embroider their suspenders with their initials. They could gaze at one of the world’s first internal combustion engines, a technology that would in the next 50 years remake the world by powering a million cars, tractors, and tanks. They could see the first Remington typewriter and Edison telegraph system.

In the Main Exhibition Building, a little-known teacher for the deaf caused a riot with his science experiment. In one room, the teacher held up a little metal piece to his mouth and read Hamlet’s soliloquy into a transmitter. In a separate room, the emperor of Brazil, sitting with an iron box receiver pressed against his ear, heard each word—to be or not to be—reverberating against his eardrum. The teacher’s name was Alexander Graham Bell, and the instrument in question had three months earlier received a patent as the world’s first working telephone.

A few yards away, a scientist named Joseph Lister was having much less success trying to explain his theories of antisepsis to a crowd of skeptical American doctors. He claimed that the same tiny organisms that Pasteur said turned grape juice into wine also turned our wounds into infestations. Lister encouraged doctors to sterilize wounds and to treat their surgical instruments with carbolic acid. But American doctors laughed off these suggestions. Dr. Samuel Gross, the president of the Medical Congress and the most famous surgeon in America, said, “Little if any faith is placed by any enlightened or experienced surgeon on this side of the Atlantic in the so-called carbolic acid treatment of Professor Lister.” American surgeons instead believed in “open-air treatment,” which is exactly what it sounds like.

Here are three characters of a story: James Garfield, Alexander Graham Bell, and Lister’s theory of antisepsis. They were united at the 1876 centennial. They would be reunited again in five years, under much more gruesome circumstances, brought together by a medical horror show that would end with a dead president.

If you have questions, observations, or ideas for future episodes, email us at PlainEnglish@Spotify.com.

Summary

In the following excerpt, Candice Millard talks to Derek about what drew her to James Garfield’s story and some of the incredible things he achieved throughout his life.

Derek Thompson: It is an honor to talk to you. Your book Destiny of the Republic is absolutely splendid. Let’s start here: You are a historian. You have written books about Winston Churchill, Teddy Roosevelt, giants in history, two of the most famous men maybe of the last 200 years. Why James Garfield? What drew you initially to the story?

Candice Millard: Well, it wasn’t the fact that he was president, and it wasn’t even the fact that I knew anything about him. Like most Americans, unfortunately, all I knew about him was the fact that he had been assassinated so early in his presidency. I was actually doing research on Alexander Graham Bell, and I wanted another book that had a lot of science in it. I was just doing general research. And I stumbled upon the story of him trying to save Garfield’s life after he was shot. And I thought, Why would he do that? Obviously Garfield was president, but Bell was young. He had all this attention for the first time. He had a little bit of money for the first time. He had so many ideas, and he dropped absolutely everything he was doing to try to save Garfield. And I thought, Huh, I wonder what Garfield was like. So I started researching him, and I was just blown away. He was just an extraordinary human being who’s been almost completely forgotten, and it just captured my heart and my mind and my imagination, and I really wanted to try to tell the story.

Thompson: In addition to being an extraordinary figure, Garfield is a beautiful writer, and each of your chapters began with an excerpt from his papers, his diaries, his letters as you collected them and read them. And I’m going to try to do my best as we lead listeners through this story of James Garfield to seed this story with little quotes from your books. We can hear from Garfield himself because he really is an incredibly poetic, lyrical writer. Let’s start at the very beginning. Tell me about James Garfield’s birth, his rise to prominence from his childhood in Ohio.

Millard: So he was incredibly poor. He was our last president born in a log cabin. His father died before he was 2 years old. He didn’t have shoes until he was 4 years old in Ohio. And so he had an older brother and his mother, who just saw very early on that he had a very unusual mind, and they worked really, really hard to save a little bit of money to try to send him to college. So he went to what was then called the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute; it’s now Hiram [College] in Ohio. But to still help pay his tuition, his first year he was a janitor and a carpenter. But he was so brilliant that by his second year—while he himself is still a student, he’s just a sophomore in college—they made him a professor of literature, mathematics, and ancient languages.

He was an incredible classicist. He knew huge parts of the Aeneid by heart in Latin. By the time he was 26, he was the university president. In Congress, while he was in Congress, he wrote an original proof of the Pythagorean theorem. So I don’t know if you can name a congressman today who could do that. I can’t. But he was just a genius. He really was just a brilliant, brilliant—he was also, as you said, an incredible writer. He was also an incredibly magnetic and persuasive and powerful speaker, and he was known early on in Congress for being that.

But to me, what makes him more interesting—even than his mind—was his heart. He was really a decent, kind human being. He wasn’t, you mentioned, I wrote about Theodore Roosevelt. He wasn’t like Roosevelt, who was sort of the hero of every drama, right? Garfield was sort of the calmest, wisest man in the room. So he hid a runaway slave. He was instrumental in bringing about Black suffrage. He was a hero in the Union Army. When he gave his inaugural address, Frederick Douglass was standing next to him. So he was an incredibly progressive, again, just a decent human being.

Thompson: And the rags-to-riches story is almost a cliché in American history, and the concept of the American dream is dutifully controversial today. But Garfield’s story is an incredible example of the American dream, and in fact, he wrote about the concept of social mobility in a way that I found absolutely gorgeous. He wrote, “There is no horizontal stratification of society in this country like the rocks in the earth, that hold one class down below forevermore, and let another come to the surface to stay there forever. Our stratification is like the ocean, where every individual drop is free to move, and where from the sternest depths of the mighty deep any drop may come up to glitter on the highest wave that rolls.”

That is lovely, and clearly Garfield himself rose up from the sternest depths of the mighty deep. No shoes in Ohio winters at 4 years old; 22 years later, he is the president of a college. So to your point, he makes his way to Congress. Briefly, before we go to this famous moment at the Republican Convention in 1880, what was he like as a congressman? What did he fight for in Congress?

Millard: Well, as I mentioned, he was instrumental in bringing about Black suffrage. And you just quoted something he wrote. If you have a chance, any of your listeners have a chance, to read the speech that he gave on the floor of Congress on behalf of Black suffrage, I strongly encourage you to do that. It’s so moving and powerful. And today we think, Of course, who would be against that? But as we know, unfortunately, many people were against it, and it’s just so powerful. He was a very, very strong abolitionist. He was also a big finance guy. He believed very strongly in hard money, believing that we should always have gold to back up paper money. He was very, very invested in the creation of the Department of Education because education had obviously been his own salvation, and he knew that it was the hope and promise of this young country. So those were the kinds of things that he was involved in as a congressman.

Host: Derek Thompson

Guest: Candice Millard

Producer: Devon Baroldi