Plain English With Derek Thompson

Fraud, Scandal, and Failure in the Fight Against Alzheimer’s Disease

Hosts

About the episode

Why is it so hard to find a cure for Alzheimer’s? A simple answer is that the brain and its disorders are complicated. But as today’s guest, Charles Piller, writes, there’s another, more sinister factor at play. His new book, Doctored, traces an incredible, true story of fraud, arrogance, and tragedy in the quest to cure Alzheimer’s.

In the last few years, some of the most famous and revered neuroscientists in America have been accused of doctoring images in research related to Alzheimer’s and neuroscience—even as they raised tens of millions of dollars in funding based on this doctored science and set up clinical trials for thousands of patients based on these manipulated results. At the same time, a silent conspiracy of groupthink starved this field of research of fresh ideas, with catastrophic consequences. Piller explains how he broke the story of what might be this century’s biggest scandal in American medical science.

If you have questions, observations, or ideas for future episodes, email us at PlainEnglish@Spotify.com.

Summary

In the following excerpt, Charles Piller breaks down for Derek the dominant theory that has shaped Alzheimer’s disease research since the early 20th century.

Derek Thompson: You write in your book that for decades, Alzheimer’s research was shaped by the dominance of a single theory, a single protein theory called the amyloid hypothesis, and that in the last few years and even decades, nearly every drug approved for Alzheimer’s dementia in the United States is based on this theory. What is the amyloid hypothesis?

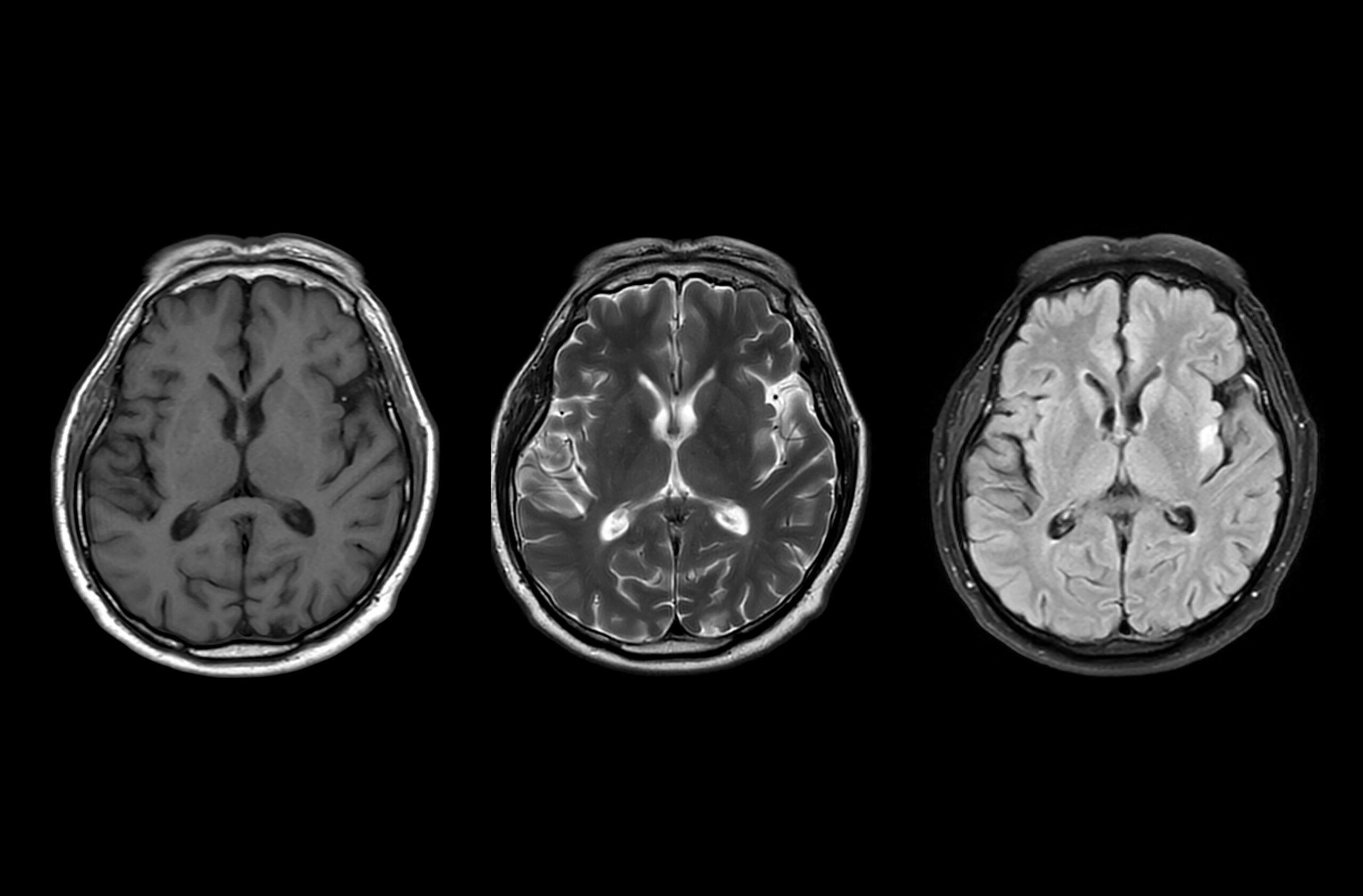

Charles Piller: OK, I’m going to wind us back all the way back to 1906, just briefly, which was the date of the kind of quote, unquote discovery of the disease by [Alois] Alzheimer, a German scientist, namesake of the disease. And he was a pathologist and a clinician, so he was treating a patient who had dementia, and this person ultimately died. And he did an autopsy on her brain, and he saw in the brain copious amounts of amyloid plaques—and this amyloid is a type of protein, and the sticky plaques are the sort of characteristic description of what scientists see as characteristic of this disease—and also another protein that’s called “tau” that tangles within nerve cells. So you have the plaques outside of the nerve cells—and also, it would be later learned that other forms of amyloid protein, soluble forms of the protein, were floating around in the fluid that bathes the brain—and also these tangles.

And Alzheimer said, basically, this combination of factors, plaques, tangles, and dementia, that’s the disease. And it caught on. It was named after him. But for decades, there wasn’t much progress or even enough interest in the disease to take a deep dive into what might be going on biochemically, partly because it’s a pure demographic explanation. There weren’t that many people living to old age, the age that Alzheimer’s normally has as the age of onset. And consequently, it just wasn’t that big a medical problem. But advances in other medical fields drove demographics differently. People started living longer. A huge population of older people began to be dominant in the population compared to their earlier numbers, and a lot of those people were getting this disease. So it suddenly had a gigantic infusion of interest in not just Alzheimer’s but in the original thinking about the disease: plaques, tangles, dementia, the amyloid idea.

And so in the early ’90s, this was conceptualized into something called the “amyloid cascade hypothesis” by certain scientists. And, essentially, it’s very simple. It works this way: Amyloid plaques and other forms of amyloid protein start a cascade of biochemical effects in the brain that eventually leads to dementia.

Thompson: So you’ve brought us up with a history of Alzheimer’s research from the early 20th century into the late 20th century. Between the 1990s and today, how did the amyloid hypothesis take over Alzheimer’s research and drug development?

Piller: Well, there were a few reasons [for its takeover]. One is—let’s be fair to the scientists who developed this hypothesis—this made an incredible amount of sense. You look inside the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and you see copious amounts of amyloid plaques, other forms of amyloid, and you see these tangles inside their nerve cells. So of course there was a lot of interest in this. It was logical. And people pretty much jumped on that bandwagon when they started to understand that this combination of factors was so logical.

Subsequent to this hypothesis being framed out by scientists, a flood of money came into the field. The National Institutes of Health began to send hundreds of millions of dollars in the direction of exploring whether amyloid proteins really were the source of this and how best to attack that problem. And so, because of all this funding, because of all the scientific interest, it grabbed a huge amount of mindshare in the scientific community.

There were always alternative explanations for Alzheimer’s disease, always ideas that were contrary to this lockstep approach with the amyloid hypothesis. But they were, in essence, crowded out, not just because the hypothesis made some sense but because powerful figures within the scientific community were favoring that hypothesis and opposing spending a lot of money on other kinds of research associated with the disease.

This excerpt has been edited and condensed.

Host: Derek Thompson

Guest: Charles Piller

Producer: Devon Baroldi