The 17 Greatest Best Picture Title Defenses

With Bong Joon-ho’s long-awaited ‘Parasite’ follow-up, ‘Mickey 17,’ about to grace our screens, we’re counting down the best films from directors coming off of Oscars gloryIt’s widely understood in sports that how you defend winning a championship helps define how that championship is perceived. If you roll over and collapse the following season, your title looks like a fluke. This is partially why dynasties are so revered; maintaining that hunger, that drive for greatness, takes immense determination, especially once what Pat Riley called “The Disease of More” settles in.

The same can be true with movies. After a film wins Best Picture at the Oscars, its director will never have a brighter green light or more blank-check offers in their life. It’s the moment studios and financiers will say yes to a director’s wildest passion project, but also the moment the director is most likely to be swallowed whole by their own ambition and hubris.

The story of what directors do immediately following a Best Picture win is the story of Hollywood’s biggest dreams and loudest bombs. Several filmmakers, including William Wyler, William Friedkin, and Steven Spielberg, used that moment of prestige to launch their own autonomous studios or production companies, mostly to ill effect. Others have used that opportunity to mount three-hour war epics or grandiose Broadway musical adaptations, bring to life the Torah or the Bible, or even remake classics like King Kong.

At a moment when Mickey 17, Bong Joon-ho’s long-awaited Parasite follow-up, is about to hit theaters on Friday, and excitement for Christopher Nolan’s The Odyssey is quickly reaching a fever pitch, and questions about what Sean Baker should do next are already being debated, it’s the perfect time to look at the best examples of directors following up a Best Picture win.

Mickey 17 will officially become the 93rd follow-up to a Best Picture winner, and those sequels of sorts are all over the qualitative map. Some are legendary masterpieces. Some are among the most infamous fiascos in Hollywood history. At least one is both.

Here at The Ringer, we’re most interested in celebrating champions. So, in honor of Bong Joon-ho’s latest effort, we present: cinema’s 17 greatest title defenses.

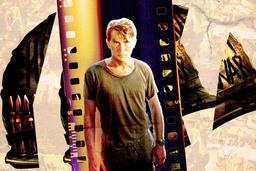

17. Heaven’s Gate (Michael Cimino, 1980)

Four movies were primarily responsible for ending what we think of as the New Hollywood era from 1967 to 1980. On the one hand were Jaws and Star Wars, which created the blockbuster (and the insatiable appetite for it). On the other hand were Apocalypse Now and Heaven’s Gate, two Best Picture follow-ups by directors who got so drunk with power and spent so much money that they forever changed the willingness of studios to give filmmakers carte blanche.

To this day, Michael Cimino’s four-hour epic about the Johnson County War in 1890s Wyoming remains Hollywood’s ultimate cautionary tale. Its out-of-control budget grew so high—and its box office failure was so deafening—that it effectively bankrupted United Artists and forced the studio’s 1981 sale to MGM.

But 45 years on, with its infamy at least somewhat forgotten to time, it’s easy to look at Cimino’s follow-up to The Deer Hunter with a fresh set of eyes. And what you see is the great movie that the men writing the checks desperately hoped it would be. To be fair, the film is bloated, and you could probably cut nearly an hour of its 219-minute runtime without losing much. But several of the scenes really pop, and the dusty golden-hour vistas captured by cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond are a wonder to behold.

Star Player: Vilmos Zsigmond’s imagery

Unsung Hero: Isabelle Huppert, in her first significant role in an American film, is the story’s heart and soul

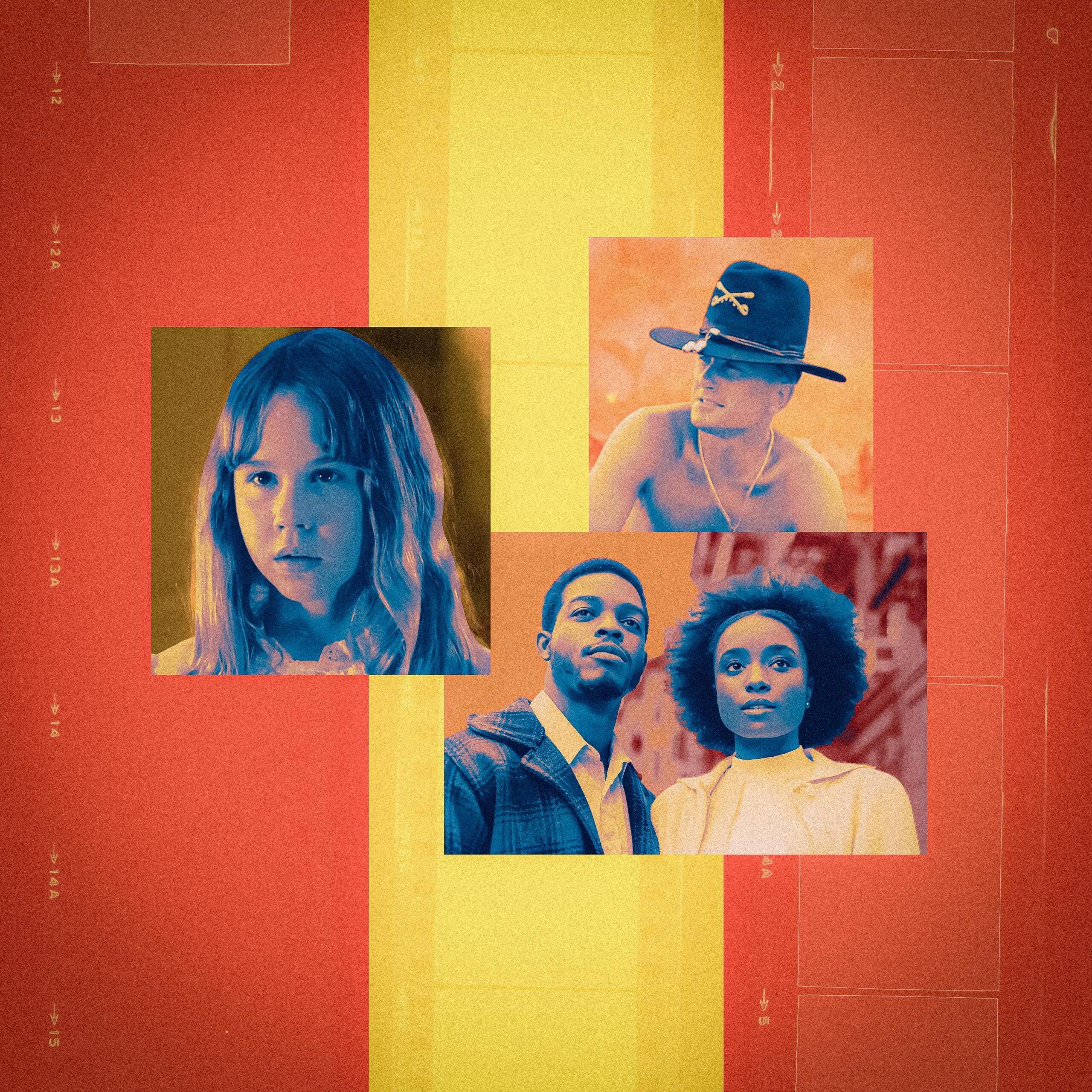

16. A Perfect World (Clint Eastwood, 1993)

Clint had been directing genre movies for over 20 years—to virtually no awards attention at all—before 1992’s Unforgiven suddenly turned him into an Oscar darling and dramatically changed the arc of his career. Spurred on by the themes that made Unforgiven so potently resonant with people, Eastwood began an exploration into the perpetuation of cycles of violence, which has continued in his films to this day.

A Perfect World was Clint’s first film under the auspices of being an A-list director, and it remains one of his very best. Kevin Costner gives a wonderfully nuanced performance as an escaped convict who kidnaps a young boy as insurance, but quickly becomes taken by the child, and morphs into the father figure that neither of them ever had. If most of Eastwood’s best films are about the inevitability of violence begetting more violence, A Perfect World is the rare film that understands those cycles don’t have to repeat in specific patterns, and occasionally they can evolve into something different and unexpected.

Star Player: Kevin Costner, at the absolute apex of his megastardom

Unsung Hero: T.J. Lowther, the child actor who made his character’s need for a father figure feel all too real

15. One, Two, Three (Billy Wilder, 1961)

After the twin triumphs of 1959’s Some Like it Hot and 1960’s The Apartment (the latter won Best Picture), Billy Wilder slammed down on the gas. One, Two, Three might be the most rapid-fire comedy ever made; even though the film runs a brisk 104 minutes, you could easily convince me the script was 250 pages long considering how much dialogue star James Cagney fires off seemingly every second.

Cagney plays a West Berlin Coca-Cola exec desperately trying to hide the fact that his boss’s daughter has been sneaking to East Berlin every night to shack up with a Communist revolutionary. Filmed on location as the Wall was going up, One, Two, Three is a killer mainstream comedy with wonderfully subversive undertones. And Wilder—who began his career in Berlin before fleeing to America in 1934—sure had a blast skewering Iron Curtain fascism.

Star Player: Cagney, making his final film appearance for 20 years

Unsung Hero: The rat-a-tat script by Wilder and his writing partner, I.A.L. Diamond

14. The Day of the Jackal (Fred Zinneman, 1973)

In the seven years it took Fred Zinneman to follow 1966’s A Man for All Seasons, everything about the cinematic landscape changed. New Hollywood had taken over; movies were now filled with antiheroes, sex, and graphic violence, and filmmakers from Zinneman’s generation (he’d been directing since the 1930s) were basically left for dead. But the amazing thing about The Day of the Jackal is that it feels as perfectly of its time as any other ’70s classic.

Adapted from the eponymous novel about an assassination attempt on Charles de Gaulle, The Day of the Jackal gets about as granular into planning and investigating a murder as any movie ever had up to that point. Zinneman stuck to his guns and cast unknowns, shot on location all across Europe, and ended the film on a bitter, detached note that’s pure ’70s nihilism. (The recent Peacock adaptation of the same name isn’t bad, either.) Squint and you can almost see the first David Fincher movie.

Star Player: Zinneman, who adapted to the changing times in a way that almost none of his contemporaries were able to

Unsung Hero: Future Bond villain Michael Lonsdale, as the French investigator on the case

13. Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow, 2012)

Kathryn Bigelow’s follow-up to 2009’s The Hurt Locker was originally supposed to be about the failure of U.S. intelligence to find Osama bin Laden. But real life intervened, and bin Laden was killed just as the film was about to start shooting. So Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal scrapped most of what they’d done and started over. Amazingly, the completed film opened just 19 months later.

In practical and economic terms, Zero Dark Thirty is kind of the best-case scenario for a Best Picture follow-up. The expert style and craft of its predecessor was retained, but the ambition and scale were ramped up while the budget was kept relatively under control (a modest $40 million). And the film made a healthy profit, generated a ton of awards attention, and received numerous Best-of-the-Year plaudits. Working under the intense spotlight of high expectations for the first time, Kathryn Bigelow almost made it look easy.

Star Player: Jessica Chastain, giving a career-best performance as the CIA investigator obsessed with finding bin Laden

Unsung Hero: Kyle Chandler, who went toe-to-toe with Chastain and lived to tell about it

12. Burn After Reading (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2008)

At first glance, it may look like the Coen brothers followed their most serious film, 2007’s Best Picture–winning No Country for Old Men, with their least serious film, a romp about deeply stupid people turning to crime because they’re desperate for plastic surgery and dildo chairs. And it’s true that no A-list cast—headlined by Frances McDormand, George Clooney, John Malkovich, Brad Pitt, and Tilda Swinton—has ever looked so effortlessly hapless.

But while other Coen brothers’ farces are nearly as unserious as they seem, Burn After Reading is ultimately just as biting an indictment on America as the Oscar darling that preceded it. The movie isn’t about stupidity as much as it’s about the assumption of intelligence getting bestowed upon absolute morons who don’t actually possess it. It could have been called No Country for Smart Men, and no film more deftly explains contemporary America.

Star Player: John Malkovich, who is all of us when he screams “You are part of a league of morons. You’re one of the morons I’ve been fighting my whole life!”

Unsung Heroes: Brad Pitt’s dance moves (and the dildo chair, obvs)

11. Widows (Steve McQueen, 2018)

Steve McQueen’s first three films comprise a focused triptych about the reasons we suffer—Hunger showed suffering for a cause, Shame portrayed suffering as an addiction, and 12 Years a Slave was an uncompromising portrait of suffering from abject cruelty. But McQueen’s canvas expanded after the latter won Best Picture, and in remaking an old British miniseries with Gone Girl writer Gillian Flynn, McQueen crafted a taut heist thriller that proudly wore its grander ambitions on its sleeve.

Widows sometimes tries to do too much, and perhaps no movie could successfully provide profound commentary on corruption, crime, gender, policing, and race all at once. I’ve often wondered if Widows might have worked better as a prestige limited series (where it probably would have netted four times the viewership). But this dazzling degree of ambition and explosive follow-through is everything one hopes for with a Best Picture title defense.

Star Player: Viola Davis, who eats up the screen

Unsung Hero: Daniel Kaluuya, embodying one of the more menacing movie villains in recent memory

10. Avatar (James Cameron, 2009)

Unless someone eventually wins Best Picture for their supposed final film—Quentin Tarantino, are you listening?—James Cameron will probably always hold the record for taking the longest to follow-up a Best Picture winner. But when Avatar finally hit theaters 12 years after Titanic, it was a true game changer for the industry, launching the 3-D craze and advancing motion-capture technology far beyond even what Peter Jackson had done (more on this below).

You can cynically look at Avatar as a shameless rewrite of Dances with Wolves and FernGully: The Last Rainforest, but that misses the point. One doesn’t watch a James Cameron movie for its writing. (“Unobtainium” should’ve probably tipped you off to that.) One watches a James Cameron movie for the sensory experience of being transported into a James Cameron movie. And one of the enduring truisms of cinema is that Big Jim does not miss.

Star Player: James Cameron, of course

Unsung Heroes: Every single tech person and animator that made Avatar’s visuals come to life

9. Broadcast News (James L. Brooks, 1987)

The first century of cinema was almost exclusively defined by the male gaze, and the number of films that got smart women in high-profile jobs truly, unproblematically right is pathetically low. But however small that list is, Broadcast News is likely at the top. That’s a testament to Holly Hunter breathing perfect, vibrant life into Jane, the woman who’s always the smartest person in the room (“It’s awful!”); but also to writer/director James L. Brooks, who followed up 1983’s Terms of Endearment with something even funnier, snappier, and more heartfelt.

If Bull Durham is the perfect melding of rom-com and sports movie, Broadcast News is the perfect melding of rom-com and workplace drama. Hunter stars alongside William Hurt and Albert Brooks, who all give career-best performances and were all nominated for Oscars (with Brooks up for Supporting Actor, in one of the earliest instances of category fraud). But James L. Brooks’s script is the real star, giving us one of cinema’s greatest love triangles.

Star Player: Who else but Holly Hunter?

Unsung Hero: Albert Brooks, who describes the devil better than anyone else ever has or ever will

8. King Kong (Peter Jackson, 2005)

After the Detroit Pistons won the 2004 NBA title, Rasheed Wallace famously bought WWE championship belts for everyone on the team to wear the next season. When Peter Jackson followed his Lord of the Rings triumph with a remake of King Kong—the same year those Pistons tried to defend their title—he was essentially doing the same thing.

Jackson’s endearingly decadent passion project has some glaring flaws: the portrayal of an Indigenous tribe is deeply problematic, and several of the film’s CGI set pieces are almost masturbatory. But King Kong was cinema’s greatest leap forward in CGI brilliance since T2: Judgement Day, and you forgive its brazen showboating because the results really look that good. Most impressive, though, are the tender scenes between Kong and a never-better Naomi Watts, which for my money are some of the most achingly beautiful moments in 21st century film. (Yes, I’m a sap.)

Star Player: Naomi Watts, whose deeply emotional performance is all the more impressive when you realize she did almost all of it opposite a green screen

Unsung Heroes: Andy Serkis, whose motion-capture work really does deserve an Oscar one of these days, and James Newton Howard, whose lovely score perfectly complements sequences like this:

7. If Beale Street Could Talk (Barry Jenkins, 2018)

A funny thing happened after Moonlight shocked the world to win Best Picture. Barry Jenkins didn’t dramatically raise the stakes on his ambition; he didn’t spend an exorbitant amount of money to make an epic period piece; he didn’t retreat backward into a genre film, or zag as far from Moonlight as possible. (Most of these moves would come later, with The Underground Railroad and Mufasa.)

No, he just made another perfect little Barry Jenkins film. Aside from the franchise IP of it all, the reason it was so sad to see him make a CGI Lion King movie last year is because no one has ever captured the power and beauty of human faces like Barry Jenkins. That’s never been more true than it is here, and like its predecessor, If Beale Street Could Talk is one of the great treasures of the modern American canon.

Star Player: Barry Jenkins, whose intimate gaze brings the characters to life

Unsung Hero: Regina King, who won a Supporting Actress Oscar for her tender portrait of motherhood

6. Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

By the time The Godfather: Part II won Best Picture for 1974, Francis Ford Coppola was on a roll like no other. He’d written five films in the 1970s and directed three of them. Three won Best Picture, and the fourth won the Palme d’Or from Cannes. And then he went to the Philippines to mount Hollywood’s first attempt to reckon with the specter of Vietnam. The shoot was supposed to take four months but instead lasted 16 (and editing took two years), the lead actor was replaced and then his replacement had a heart attack on set, the production budget nearly tripled, entire sets were wiped out by a typhoon, and Coppola went so crazy that there’s a feature-length documentary about it.

And yet. The resulting film isn’t just a masterpiece of American cinema (and it netted a second Palme d’Or for Coppola), but it’s probably the single piece of pop culture most responsible for shaping the American opinion of the Vietnam War, and arguably war in general. The Best Years of Our Lives had already introduced PTSD into the American consciousness 30 years earlier (more on this below), but Apocalypse Now was the film that inculcated within us the capacity for war to truly break someone, to the extent that barely any humanity remained.

Star Player: Robert Duvall, whose Lt. Colonel Kilgore is one of culture’s most unforgettable portraits of masculinity gone wrong

Unsung Heroes: The Doors, whose epic 1967 song “The End” opens the film with one of cinema’s defining needle drops

5. The Talented Mr. Ripley (Anthony Minghella, 1999)

The prevailing joke about 1996’s The English Patient was that you had to be both English and patient to like it, and fair or unfair, Harvey Weinstein’s first Best Picture winner came to represent the most pretentious kind of “Who actually likes this?” Oscar bait. But director Anthony Minghella got the last laugh, following it up with one of the most acclaimed and adored films of arguably the best movie year ever.

If all movies were ranked purely by how beautiful everyone and everything looked, The Talented Mr. Ripley would unquestionably be no. 1; Jude Law is so disconcertingly gorgeous in the film that he could make murderous Ripleys of us all. But beneath that seductive facade lurks Matt Damon’s rangiest and most vulnerable performance, Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s best dick-swinging supporting turn, and the greatest screen adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s most enduring character. (Yes, even over last year’s terrific Netflix effort.)

Star Player: Matt Damon, displaying the full breadth of his talent

Unsung Heroes: Everyone in Jude Law’s gene pool

4. The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973)

Today it might not feel particularly unusual for an A-list filmmaker to try their hand at a pure horror film, but in 1973, winning Best Picture and then immediately pivoting to a movie about Satanic possession was completely unprecedented. William Friedkin has always been drawn to people living in extreme circumstances, though, and after winning Best Picture for the greatest cop movie ever (1971’s The French Connection), taking on another disreputable genre was probably an irresistible challenge.

Even still, no one was prepared for how good The Exorcist would be, nor for how much money it would make. (Adjusted for inflation, roughly $3 billion!) It almost completely reinvented the horror genre and became the top grosser in the history of Warner Bros. Pictures. Sadly, it would be the last major hit of Friedkin’s troubled career.

Star Players: The makeup and effects teams that turned a 13-year-old girl into one of the scariest things anyone had ever seen

Unsung Hero: Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells album, which was adapted into the film’s endlessly creepy score

3. The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)

Here is Coppola’s first Palme d’Or winner. I rewatched his follow-up to The Godfather a few days before the news of Gene Hackman’s death, so the greatest performance in a career overflowing with great performances was fresh in my mind as the memorials began rolling in. Although the film is ostensibly about careful listening, the most profound aspect of watching it is Hackman’s endlessly tortured face, especially in a final shot that remains one of American cinema’s most haunting images.

Typically, when a grand American epic like The Godfather wins Best Picture, its director feels compelled to go even bigger for their next film, and that’s exactly what Coppola did with Apocalypse Now the second time he won Best Picture. But he went the opposite route for The Conversation, which succeeds as both one of the great ’70s paranoia thrillers, and also as an intimately probing character piece. That’s an incredibly difficult double act to pull off.

Star Player: Gene Hackman

Unsung Hero: Walter Murch, who did double duty on both the film’s editing and sound teams

2. The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler, 1946)

William Wyler is the only director to make three Best Picture winners, and all three of his title defenses are well worth seeking out (though the gay panic and shame at the heart of 1961’s The Children’s Hour hasn’t aged well). But even the caustic ambiguity of 1949’s The Heiress doesn’t compare to Wyler’s first Best Picture follow-up, a deeply powerful and intimate look at three American soldiers struggling to reacclimate to normal life following their horrific experiences in World War II.

The Best Years of Our Lives became the highest-grossing film of the 1940s, and its extraordinary success effectively introduced the idea of PTSD into the cultural mainstream. It also represented Wyler’s own struggles—following 1942’s Best Picture winner, Mrs. Miniver, Wyler spent several years in combat making World War II documentaries, which led to hearing damage while making Thunderbolt! and the death of his cinematographer while filming The Memphis Belle.

The Best Years of Our Lives consequently became one of only two Best Picture title defenses to also win Best Picture itself (the other is below), and its nine-Oscar haul included a second Best Director honor for Wyler and Oscars for two members of the film’s cast, including Harold Russell—a disabled veteran who lost both his hands in the war, in his first film role.

Star Player: Harold Russell

Unsung Hero: Screenwriter Robert E. Sherwood, who won three Pulitzers as a playwright before penning this Oscar-winning script

1. Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962)

If following up a Best Picture winner is often a battle of ambition versus hubris, genius versus ego, then Lawrence of Arabia is the ultimate expression of taking those battles head-on and winning. After 1957’s The Bridge on the River Kwai grossed 10 times its budget and won Best Picture, director David Lean was in position to get anything he wanted. And what he wanted was to spend an exorbitant amount of money to film a patient, four-hour drama in a desert halfway around the world, starring a completely unknown lead actor.

Nothing about Lawrence of Arabia should have worked. Everything about it did.

At the end of a 2024 Oscar season partially defined by Sean Baker pleading with other filmmakers to ask for what they want, as well as Brady Corbet pleading with studios and production companies to actually give filmmakers what they ask for, Lawrence of Arabia remains the best-case scenario for what those practices might hope to achieve—a timeless masterpiece that channels every dream for the power of cinema into some of the most lush, unforgettable images ever to grace the big screen.

Star Player: David Lean’s vision

Unsung Heroes: Freddie Young’s epic cinematography and Maurice Jarre’s timeless score